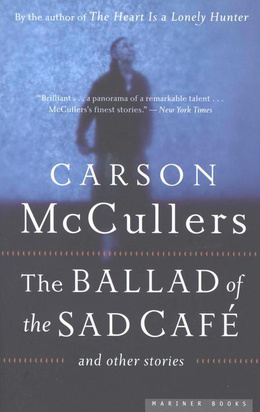

Carson McCullers, The Ballad of the Sad Café (1951).

Recommended for adults.

Eleven years after this child prodigy published The Heart is a Lonely Hunter (1940) at the tender age of twenty-one, she produced this novella. It is a meditation on love, not on what it is, but on what it does to people, even the most unlikely ones.

In a tiny mill town deep in the pines of northern Georgia Miss Amelia comes to love the drifter Lymon, but he in turn falls under the spell of the no-good Marvin Macy. These loves are not of the flesh, I add. But slowly, Amelia discovers that she likes doing things for Lymon, and the more she does, the more he takes it as his due with nary a word of thanks. This she does not mind.

Then Marvin reappears and slowly Lymon comes to admire and imitate Marvin. Along the way McCullers offers a glimpse of the people and practices of that isolated community. Lymon cannot bear to be parted from Marvin, and so the despicable Marvin moves in with Lymon and Miss Amelia. In time she is displaced from her own home to allow Lymon to serve Marvin.

I read a lot of Carson McCullers’s novels in high school and college, and having re-read The Ballad of the Sad Cafe I am reminded why. The judgements are sharp, Marvin is a creep, but even so McCullers extends a compassionate gaze on him, too: He is the way God made him, part of this world. Neither more nor less than anyone else.

That Lymon is a dwarf, Miss Amelia acts more like a man than many men, that Marvin’s brother is ineffectual, adds color to the account but these are only the surfaces beneath which McCullers peers, perceptive, unflinching, calm, and determined. No these oddities are what attracted a Hollywood film maker to mangle it.

My mission is clear. It is time to read anew The Heart is a Lonely Hunter and see how Sam and Mickey have aged since last I had their company.