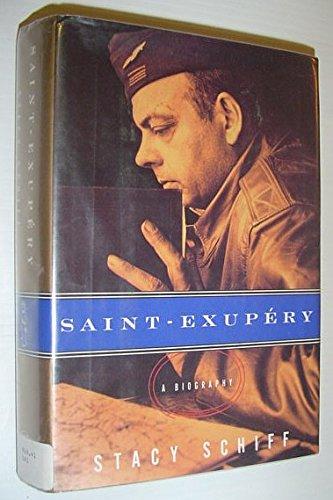

GoodReads meta-data is 560 pages, rated 4.03 by 262 litizens.

Genre: Biography

Verdict: He returned to the stardust from whence he came.

First an anecdote to create a climate of expectation:

In the 1930s a journalist telephoned a dispatch back to a Paris newspaper to an experienced secretary who was typing his report as he spoke, and …. then she stopped. The editor supervising the exchange asked if the line had been cut. No, she said, sobbing, she could not bear to go on, so moving, so simple, so powerful, so emotional, so direct was the prose of Saint Ex describing the workers with whom he had ridden in Moscow subway car.* You and I, Reader, would have seen a shabby and no doubt odoriferous collection of tired men and women going about their dreary business. But Saint Ex saw the essence and put it into words. (This secretary, by the way, was no ingenue, but rather a crusty veteran who had seen and heard it all, she thought, and that is why she was assigned this transcription.)

Antoine Marie Jean-Baptiste Roger, comte de Saint Exupéry (1900-1944) was born to be the poet of the air, and he succeeded in that, if in little else.

He was a dreamy, undisciplined man-child born to impoverished nobles, who fell further with the death of his father when the boy was four. The family thereafter lived on the largesse of others. He was the only surviving male, and much indulged by mother and sisters, who called him, as the heir, St Ex (he himself later added the hyphen (- [for those who are uneducated]) to make clear that his last name (say, on publisher’s cheques) was Saint Exupéry.

The death of his younger brother in 1915 is frequently cited as the origin of ’Le Petit Prince’ that he wrote nearly three decades later. Perhaps, but…. in this book and elsewhere he is far too readily reduced to that little book, as if his life was merely its gestation.

In that reduction are forgotten:

Courrier sud (1929) – Southern Mail

Vol de nuit (1931) – Night Flight

Terre des hommes (1939) – Wind, Sand and Stars **

Pilote de guerre (1942) – Flight to Arras

Lettre à un otage (1944) – Letter to a Prisoner

That list leaves aside the journalism during the 1930s which he found more lucrative and less arduous than novels. After ‘Le Petit Prince‘ made him famous, every scrape of paper with his writing on it was published and that is an even longer list of material he did not publish, did not write for publication, and did not intended to publish.

In the same mercenary vein, nearly everywhere this peripatetic man roamed now has a museum dedicated to him from Morocco to Rwanda to Québec to Senegal.

The boy grew up as aviation grew up. Nearly every month a new aviation feat was attempted, and some achieved. An airfield opened nearby where an industrialist tried to get into the airplane business, and the boy on his battered bicycle became an habitué. When he was not quizzing mechanics and flyers about the machines they were making and flying, he devoured the technical drawings, manuals, and reports scattered around. Thereafter this poet read technical manuals for relaxation and recreation as much as for information.

He was dreamy, inconsistent, and remained dependent on his mother for years for monetary and emotional support, and seems to have been a charming wastrel. He borrowed money constantly rather than trying to earn any, and seldom repaid the loans from friends and never to his mother though he often said he would. Finally, she had to sell the family home to pay the debts. Destitute he often bunked with pals who found he was untidy, forgetful, and a stranger to some matters of personal hygiene. Not an ideal roommate.

The sky always beckoned him and he seems only to have been himself in the air.

He was a comte and that counted for a lot, impoverished or not, in the time and place, and though his clothes were well worn, they had been of the first quality. Accordingly Monsieur le comte was often invited to society parties, dinners, dances, receptions, weddings, and he sometimes went, encouraged by his mother who perhaps thought a wife might find him there. He was by the standards of the time a bear of man, who shambled and was shy in company and that was sometimes taken as aristocratic hauteur and that added to his attraction for some. But what no one in the haut monde could abide was the broken fingernails and the oil ingrained in this finger tips from working on airplanes engines. Picture this hulk arriving in a threadbare tuxedo, announced by Monsieur le comte de Saint Exupéry shambling in with dirty fingernails and an oily handshake who would then retreat to a corner to watch.

He failed many examinations, never learned to spell (did he need glasses?), and got his lowest marks, and that is against a low tide, in French. He parlayed his military service into pilot’s wings, stationed first in Casablanca before Rick got there. In 1926 he went to to work for Aéropostale between Toulouse and Dakar in Senegal and later in Patagonia. Much of this work was solitary and he wrote a blog in the form of letters and notebooks, and out of these emerged the books listed above. There were crashes, there were adventures, there were mistakes, there was camaraderie among the airmen, who alone knew what it was like to fly in those nearly paper planes.

He was a station manager and one-man, one-plane rescuer of downed airmen in the Western Sahara. He loved that flat sand and slept outside to watch the stars, while encased in all the clothing to be had against the cold as round as the Michelin man to come.

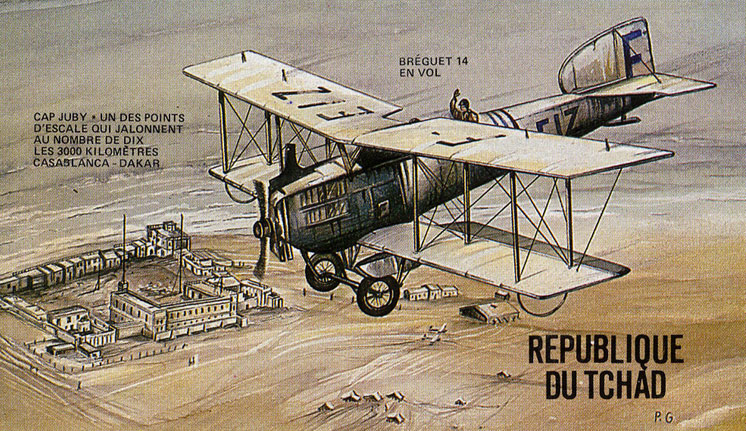

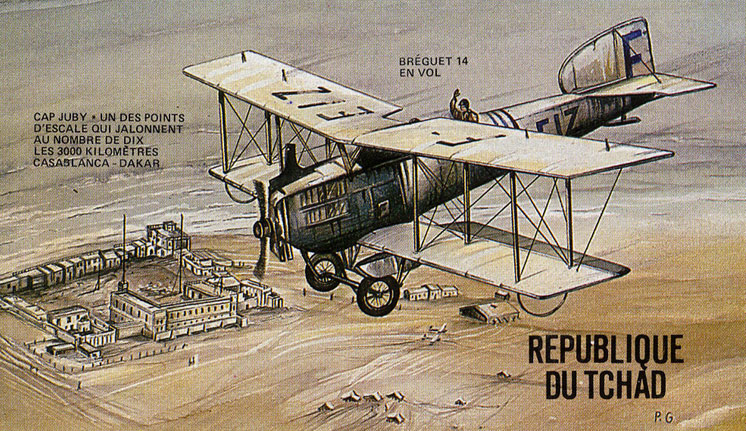

These are the kind of matchstick and canvas biplanes he flew.

These are the kind of matchstick and canvas biplanes he flew.

Much as he loved flying, he was not especially good at it. Much as he loved tinkering with engines, he was clumsy. He forgot to turn on switches, close doors, or pump oil. He dropped screws into the interstices of machinery, and simply forgot what he was doing when a daydream came by.

When he published Courrier sud he was ostracised by both the literary establishment and the aerial fraternity. In France, then as now, writing is a profession. One starts the apprenticeship in high school and continues slowly thereafter through the ranks. One does not just publish a book at twenty-nine and expect reviewers to take it seriously. Still less does one lionise the bus drivers of airplanes, as one wit put it. Apart from the publisher, Gaston Gallimard, no one took it seriously, but André Gide did, and he was a a heavy hitter in the world of letters though as ever an odd man out.

Members of the air fraternity resented him because he had retailed secret comrades’ business to an unworthy and uncomprehending public. Some also resented the fact that he made money in doing so. He was snubbed by many of his one-time colleagues and found himself shut out of flying opportunities as a result.

The result was that he was in a limbo, neither a writer, nor an aviator. That was when Gallimard and Gide promoted him as a journalist as a way for him to earn, what was always, a meagre living.

When the second war came, he returned to the air force and flew reconnaissance for l’Armee de l’Air, a thankless task with a high mortality rate. To see German troop movements the unarmed reconnaissance planes had to get low enough to be in range of small arms fire. He saw one after another of his comrades leave on missions not to return. He himself flew six such missions in combat and by some miracle survived. Much to his own surprise he became a patriot who put aside all the prejudices with which he had been born, and respected, admired, and esteemed among the pilots, mechanics, and ground staff Jews, communists, trade unionists, and black Africans and he said so. ‘Flight to Arras’ describes these days in flat and detached tone, while ‘Letter to a Hostage’ indicates his ecumenical patriotism.

As a born in the bone aristocrat, suckled on anti-semitism, and Catholic-insulated from the perfidious Revolution and its embodiment, the Republic, he had misgivings about Charles de Gaulle, principally because De Gaulle broke hard with Philippe Pétain, and to Saint Ex and many other Frenchmen Pétain was, and remained for far too long, the hero of Verdun. Moreover, and this is my interpretation, De Gaulle and Saint Exupéry were very alike, wilful, independent, obsessed, and, well, likes can repel one another. De Gaulle called everyone to duty in service of a higher cause, which is what Saint Ex had always celebrated in the abstract but not when it meant he had to get up at 5 am himself to do that duty. Or so it seems.

Later in the war he moved heaven and earth to get back into the air, flying reconnaissance, which he preferred in a P -39 Lightning which had a long range, was capable of high altitudes, and could outrun almost anything. But it was a far cry from the Breguet pictured above. It had dials, levers, switches, pumps, warning lights, none familiar to Saint Ex, but he insisted on flying. One day he took off and never came back to earth.

He was four inches over the height restriction on the pilot’s seat and took great effort to push him into it.

Finally, St Ex was mentally, morally, and philosophically neutral in politics. He did not want to see individuals reduced to political labels. Admirable that is, but how then do individuals submerge themselves in the higher cause, but to accept a part, a temporary loss of individuality? And what higher cause had Saint Ex served, after all, but the mail.

In 1944 General de Gaulle signed the award to Saint Exupéry of the Croix de guerre avec Palme.

In 1948 with Prime Minister de Gaulle in office, Saint Exupéry was recorded as Mort pour la France, a singular honour and one with material benefits for his estate by extending the copyrights on his work by thirty years.

Likewise in 1967 with President de Gaulle in office a plaque commemorating him was added to the Panthéon. Any misgivings Exupéry had were not reciprocated.

Saint Exupéry could be personally charming, and in small groups a wit and raconteur, though he had an only-child’s need always to be the centre of attention. He was, on the downside, throughout his life hungry for approbation, careless, thoughtless, heedless, and a crashing bore. He woke friends up at 3 am so that they could tell him he was genius. He knocked on the door at ridiculous hours and asked for a place to sleep, a meal, a drink and outstayed his welcome. He was the kind of guest who left half full glasses of precious whiskey on the floor for someone else accidentally to kick over. He told the same stories over and over again without a thought to how many times those around him had heard them before. Even when book sales success in the States made him rich, he seldom repaid the constant stream of loans he exacted from friends, acquaintances, publishers, editors, typists, and elevator operators. This in a man who preached human solidarity, duty, and the bond of all. For a man whose religion was duty, St Ex was astoundingly irresponsible. For a man given to hero worship he was blind to accomplishments of many around him.

It is hard to believe that this is the first book by this writer, so accomplished is it. This biography is one of the best I have ever read. It captures the subject and almost speaks with his voice in a blended of autobiography cum biography, yet retains critical distance so that the reader can see all the way around the man, and back.

She has several other biographies in print and I will go shopping for more.

The 1997 film ‘Saint-Ex’ cast Bruno Ganz, and he is perfect in mien (though not in size or shape), but everything else is a loss. The screenplay ranges through cryptic, incoherent, and juvenile, the characterisations are cardboard, the direction play school. The film gets a going over elsewhere on this blog.

* This anecdote is — consciously a homage or not — played out beautifully in ‘Der Himmel über Berlin’ (1987) with the aforementioned Bruno Ganz riding in a U-Bahn carriage.

** There are many differences between the French and English version of this book. Saint Exupéry was in New York when it was being prepared for publication and inserted material not in the earlier French edition.

He flew a Bloch 174. The navigator, photographer sat in the glass nose cone, while the pilot and the rear-facing gunner sat in the upper glass bubble.

He flew a Bloch 174. The navigator, photographer sat in the glass nose cone, while the pilot and the rear-facing gunner sat in the upper glass bubble.

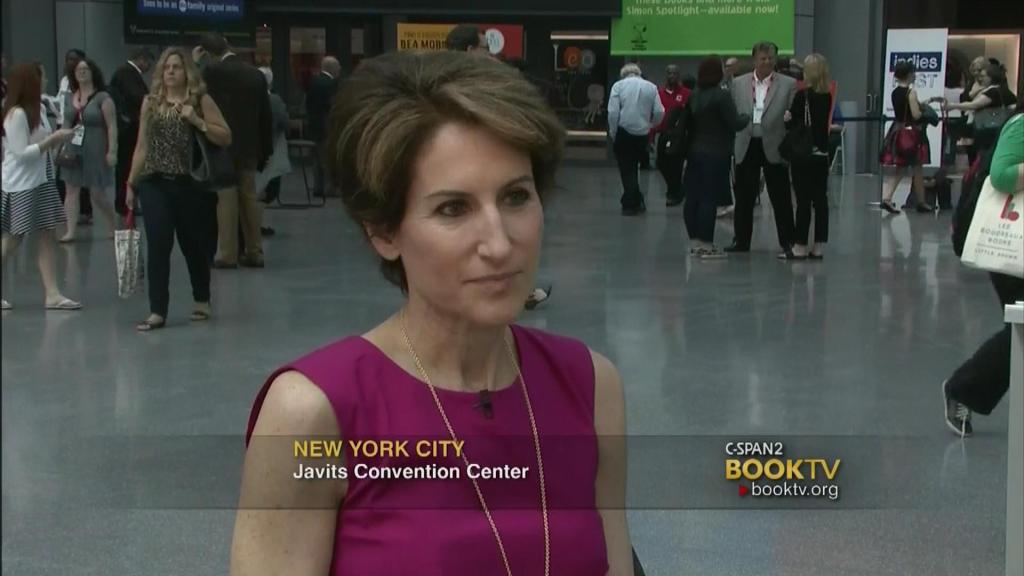

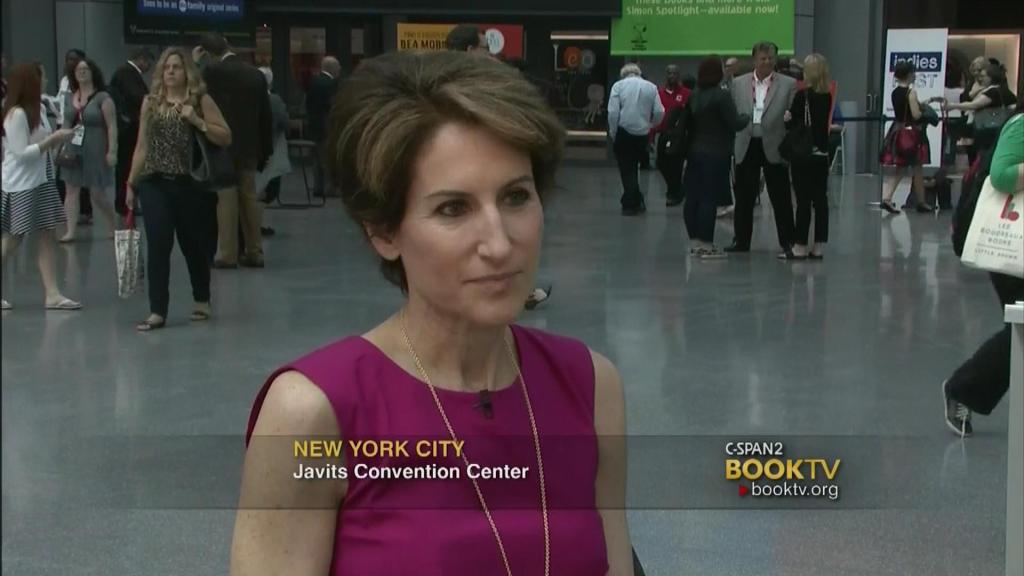

Here she is at home about that time.

Here she is at home about that time.

Asimov in the 1940s before the sideburns took over.

Asimov in the 1940s before the sideburns took over.

These are the kind of matchstick and canvas biplanes he flew.

These are the kind of matchstick and canvas biplanes he flew.