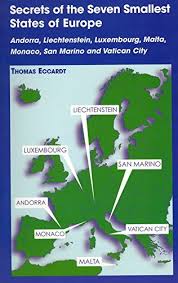

Secrets of the Seven Smallest States of Europe (2004) by Thomas Eccardt

GoodReads meta-data is 348 pages rated 3.78 by 65 litizens.

Genre: History

Verdict: The Micro Seven!

Go ahead list them!

Ordered by population.

| Population | Area in km2 | Per capita GDP US$ | |

| Vatican City | 825 | 0.49 | – |

| San Marino | 34,232 | 61.2 | 60,551 |

| Monaco | 38,300 | 2.1 | 115,700 |

| Liechtenstein | 38,784 | 160 | 98,432 |

| Andorra | 77,543 | 467 | 42,035 |

| Malta | 514,564 | 316 | 48,246 |

| Luxembourg | 626,108 | 2,586 | 112,045 |

Source: Wikipedia

These entities have most of the features of a state, though the most dubious inclusion is Vatican City. While each is unique, in general they have survived largely as a convenience to their larger neighbours, usually because they had nothing those neighbours wanted. Their existence was written into treaties at one time or another. Luxembourg was a buffer between France and Germany. Monaco made many compromises with France to retain such sovereignty as it has. Only Malta and founding member Luxembourg are in the EU, but most accept the Euro.

The only one with significant natural resources is Luxembourg which has long produced high quality steel. None is self-sufficient in food. They have all issued post stamps for revenue. Andorra made itself into tax-free shopping mall. Monaco has that casino. Liechtenstein has Swiss banking secrecy even if the Swiss no longer do. San Marino has a nonpareil stone cutting and stone working craft. Malta has Maltesers. The other major asset Malta has, along some of the other micros, is an expatriate community that supports it.

The micros represent collectively and individually a residue of European history. The Knights of Hospitaller played a major role in making Malta European when Charles V of Spain gave the island to the Knights (in return for a first round draft pick [checking to see who is paying attention]). Then there are the 13th Century Grimaldis in Monaco who passed from pirates to princes, the come-lately Grand Duke of Luxembourg, and the co-princes of Andorra, and the fiefdom that is/was Liechtenstein, a country named after a family. Only San Marino stands apart with its 13th Century origins as a republic (and by the way being a republic does not make it democratic, see a political science 101 textbook for the distinction). Of the Vatican, well it is a medieval monastery writ global.

During the Spanish Civil War, to avoid that conflict Andorra pretended to be French, and then to avoid World War II to avoid that conflict it switched to pretend to be neutral Spain. Dual nationality can be handy. San Marino supported fascist Italy but did not declare war on anyone while the Italians lost their black shirts at the casino in Monaco. During the war many (of the few) Liechtensteineans (take that spell checker!) embraced Austrian Nazism, but after the war they dusted off neutral Swiss cow bells. During World War II the German dismembered Luxembourg and its steel went into tanks, while Malta was bombed to ruination.

Luxembourg has laboured to integrate itself into Europe and the UN, and Malta has trod the path of de-colonisation along with many other African and Asian states though it seldom associated itself with them.

I am ready for Eggheads! I can distinguish Monaco from Monte Carlo, and I know how the Grimaldis got the title prince, and I am telling all! First, Mount Charles in Italian is Monte Carlo, and it is a rocky rise named for an earlier Grimaldi, and the area now is where the Croesus clan lives, as in ‘as rich as Croesus.’ Monaco City is where the casino and historic belle époque buildings are to be found.

The first Grimaldis who seized the area and ruled by the sword were nautical pirates who tired of salt water. One of them, trying to establish the legitimacy of his rule, wrote letters sent by couriers to all manner of dukes, kings, princes, popes, and signed himself as Prince of Monaco. After doing this for years and getting little response, because it was convenient in a geopolitical struggle a king of Spain wrote back and addressed him as prince to secure access for shipping to and from Naples.

Well, thereafter this Grimaldi make sure anyone and everyone knew that the King of Spain said he was a prince, and that made it so! Does that still work?

Liechtenstein is the only country in the world named after a family. Roy Licthenstein is no relation. or maybe he is and just cannot spell.

It is alleged that San Marino hosted about 100,000 refugees from World War II, about ten times the resident population. Many were Jews escaping from the German killing machine in 1943. I did find that number hard to credit.

The mechanical Turk consulted the algorithms and the stars and recommended this title after I had read concise histories of several European countries. I bit out of (idle) curiosity.