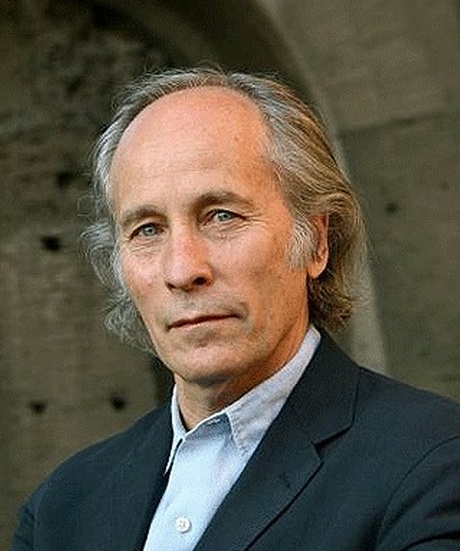

Thanks to the suggestion of a friend I went to Richard Ford’s session at the Sydney Writers’ Festival. I have read two of his novels: Independence Day and The Sportswriter. I found them easy to read but, for some reason, I was not engaged enough to want to read more. Indeed there was a ten year gap between reading these two.

http://www.swf.org.au/

However I found Ford an engaging character on the stage, and I liked his literal-mindedness: What I mean is what I say; What I say [write] is what I mean. Do not go looking for symbols or signs. Wonderful.

Likewise the host did a fine job in bringing out what Ford had to say, and the talking heads were punctuated with Ford doing some short readings from his most recent novel Canada.

Ford said in passing early in the discussion that, literal though he was, he did write with a ‘higher purpose’ and I was glad that the first question from the floor took him back to that passing aside. He explained that this higher purpose was to renew in the reader emotions and thoughts of the complete person. I have not got his words quite right, for I was not taking notes, but that is the gist. I found that explanation to be both simple and compelling. But imagine what the Derridaistas would make of that. The heavy artillery of cant and ideology, disguised as scholarship, would rumble.

Having never attended a Sydney Writers’ Festival event before I enjoyed it and just might do it again. The only false note came from the host who made a gratuitous and deprecating reference to Des Moines, Iowa. I know people make these kinds of quips without thinking, and indeed that is the point and the problem. It betrays an enduring mindset.

Here is the web description of Ford’s talk:

Richard Ford: – 15 July, City Recital Hall

One of the masters of American fiction, Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Richard Ford comes to Sydney for an exclusive event presented by Sydney Writers’ Festival. Ford visits Australia on the heels of the publication of Canada, hailed by John Banville as “an extraordinary, overwhelming book”.

With one of the most finely tuned ears in contemporary fiction Ford explores the big issues of our time with a disarming use of the vernacular. Born in Jackson, Mississippi in 1944, Richard Ford is the author of six novels and four collections of stories. Independence Day was awarded the Pulitzer Prize and the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction, the first time the same book won both prizes.

He talks to Artistic Director of Sydney Writers’ Festival, Chip Rolley.

Month: July 2012

Nicholas Nicastro, Antigone’s Wake: A Novel of Imperial Athens (2007).

There is a lot to like about it. The contrast between the public admiration of Sophocles as a playwright and then as a general contrasted to his inner doubts, confusions, and inconsistencies is nicely done, and ironic, because it makes him like a character in a play by his great rival, the upstart Euripides.

Very nice portrayal of Pericles as a wily politician who proceeds by halfs, temporizes, and stalls to see how things go. The author is ingenious in showing the immorality of the war of Greek (Athens) against Greek (Samos) – the weapons that kill women and children, torture of prisoners, treason, etc.

Loved the ending when at the Funeral Oration Sophocles’s daughter very daintily insults Pericles in public for murdering allies. ‘Noble Pericles, you have presented us with many dead citizens today. Not to celebrate the defeat of barbarians, but all to subdue an allied and kindred city [Samos]. Thank you, great general’ (p. 201-202). While Sophocles agrees with her he rebukes and punishes her, such is his inconsistent and confused nature.

Brasidas, the unSpartan Spartan

Jon Edward Martin, The Shade of Artemis: A Novel of Ancient Greece and the Spartan Brasidas (2005). This is an historical novel. I gave it five stars on Amazon USA.

A terse, focussed, well-grounded, imaginative, and at times moving account of the life and times of Brasidas, the most unSpartan of the Spartans. Brasidas emerges from Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesean War as larger than life but also obscure. If we know so much about the Athenian Alcibiades, what he drunk (too much), who he screwed (everyone), how he carried on (endlessly), we know next to nothing about Brasidas who nearly won the war single-handed. Martin offers a rounded picture of the complete man, his first love, his difficult relationship with a demanding father, a wife whom he did not love and children whom he did, the interaction with those lesser beings: helots, and the mutual perspective of Athenians and Spartans.

The story is drawn along several fault lines in Brasidas’s personal and political life and offers insights into the inner workings of the Spartan society and oligarchy paralleled to the all too public workings of Athenian democracy. For history buffs, the novel cuts away too soon from some of the major events like Mytilene but that is necessary to keep the focus on Brasidas.

I am going to read another of Jon Edward Martin’s books, and I hope he writes more.

It is very well written, no superfluous asides to pad the pages, no convoluted passages that cry out for that vanishing breed – the sub-editor, no unusual word choices that bespeak dictionary English rather than spoken English. It is certainly the equal of Nicholas Nicastro, Isle of Stone (2005) and Peter Carnahan, Pharnabazus sits on the ground with the Spartan Captains (2002). These two cover some of the same historical events. It fleshes out some of the information from Timothy Shutt’s A History of Ancient Sparta (Audible 2009) without the ponderous didacticism.