While sojourning through the historic gold fields of Central Victoria we visited M.A.D.E. in Ballarat. It is located on the site of the Eureka Stockade of 1854, and in part recounts that story for those who missed the Chips Rafferty film. It is named on the premiss that the Stockade founded Australian democracy.

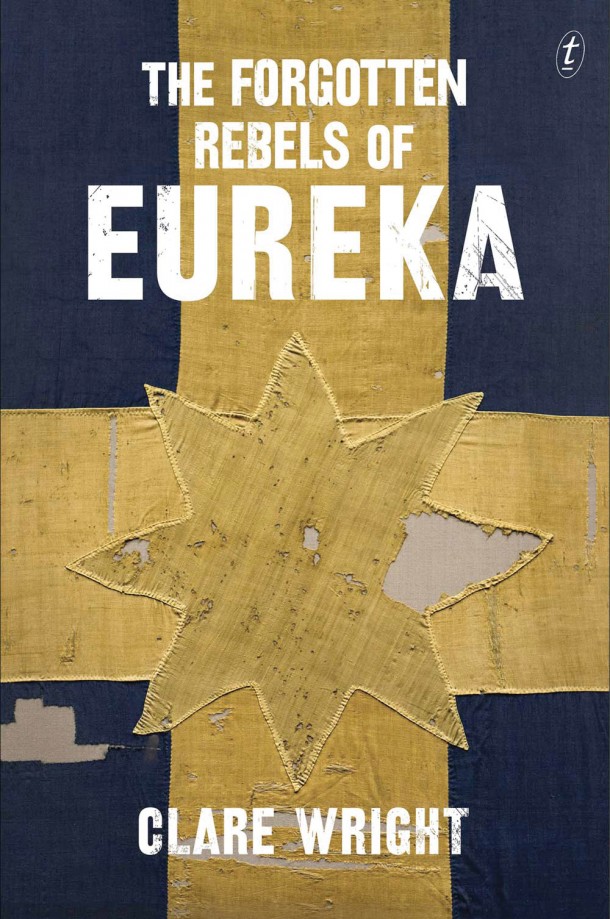

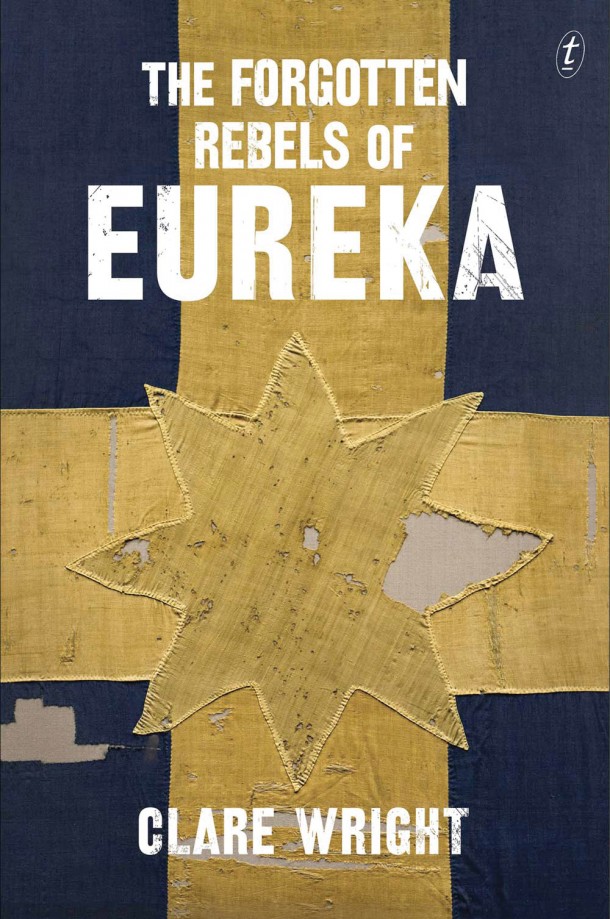

The museum is purpose built and very well designed and attractive. We particularly liked the symbolic rendering of the Stockade outside. Inside it is circular and so draws along the visitor, while mimicking the circular stockade outside. The centrepiece is the tattered remains of the homemade Eureka flag, which is surprisingly large.

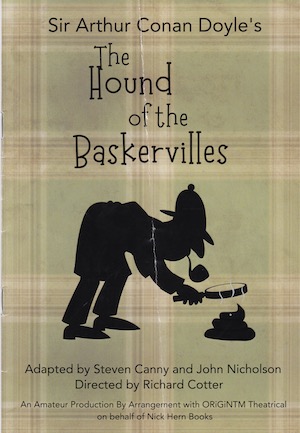

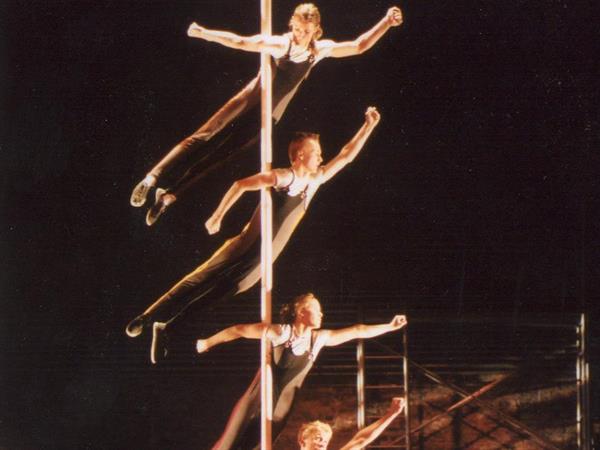

The curator at work shows the size of the flag.

The curator at work shows the size of the flag.

Ought not that to be the national flag? (And ‘Waltzing Matilda’ the national anthem; the 1977 plebiscite be damned?) Around the museum are artefacts from the days when Australian political practices developed and more general displays about the nature, value, and exercise of democracy, or so it is alleged.

But, and it is a large ‘but’ I found it as confused about what ‘democracy’ means as the rival museum in Old Parliament House in Canberra, though I thought MADE had more intellectual content and was less puerile that the Canberra version. There are comments on this latter museum elsewhere on the blog for those looking for trouble.

By the way, I typed it as MADE and not M.A.D.E. because I cannot fathom the point of the periods after the capital letters that stand for single word in an acronym. After all NASA and NATO have gotten by all these years without four additional and superfluous periods, as did the USSR. Yes, pedant that I am I did look in style guides for an explanation of that accoutrement and found none.

What the museum seems to be about is liberalism, that the individual is an autonomous being and that social and hence political arrangements should recognise and respect that. This liberty of the person is based on the capacity for autonomy and in turn that justified endowing the individual with the political rights to express and defend that autonomy. Rather than leaving individuals to defend those rights in a combative state of nature, political institutions develop to protect them in an orderly and predictable manner making social life peaceful. The foregoing is a gross gloss on Immanuel Kant who best explains this concept of autonomy with some seasoning from Thomas Hobbes.

The point to bear in mind is that persons may have social, economic, and moral liberty without political rights. A benevolent government, say a monarchy, may permit this, and in fact that is the evolution of political rights in England. But that evolution was contingent not necessary.

The Goldfields Diggers were, moreover, good John Lockean liberals and mixed their labour with the soil to create property. That term ‘digger’ took on another meaning in the trench warfare of World War I.

MADE makes no mention of Kant or Locke, but implicitly that concept of autonomy best unifies its exhibits. Some of this concept is masked by a smokescreen of jingoism according to which what is on display is Australian democracy, not democracy, but AUSTRALIAN democracy. Is it like invoking Singapore democracy when harassing journalists? Is that like dropping an apple and explaining it as the work of AUSTRALIAN gravity?

In contrast, there is little or nothing about the practice of democracy and the institutions, formal and informal, that embody it, still less any critical perspective on any aspect of it. The extension of the franchise gets a mention, but not systematically enough for this pedant. The property, racial, and gender discriminations that limited the franchise for generations was also Australian but it is passed largely in silence. Slavery in the Queensland cane sugar fields that compromised Federation from day one is likewise omitted. Indeed Australian history books coyly even now do not use the word ‘slavery’ for this quaint far north Queensland practice but maybe this is a tangent.

The evolution of the secret ballot seemed to be absent, yet as a school boy on the distant Platte I learned that the secret ballot was the (South) Australian ballot. A little jingoism on this point might be in order, or is that out of bounds because MADE is about VICTORIAN democracy? Once begun parochialism does not easily end.

Still less was there anything about the peculiarities of the hybrid Australia assembled by shopping in both Westminster and Washington for institutions. Nor is there anything about the oddities of the methods of voting and vote counting that run through Australian politics, from that Hare-Clarke system in Tasmania where everything must always be different to the endless rumours that the thirty-eighth preferences were not counted on upper house ballots in New South Wales. Some suppose this obsession with convoluted voting systems reflects a low level of social trust, which hardly fits the triumphal message of the Museum. Alan Davies used to say that.

Nor is the strange case of Queensland, speaking of differences, mentioned which has gotten by without an upper house for all these years and, despite the implications in MADE, has not been noticeably more democratic than the other states for the absence of the check on the democratic lower house.

Then there is the oddest thing of all: compulsory voting, which was legislated in 1924 as a convenience for political parties and is now a sacred totem seldom discussed rationally. When combined with the preferential ballot it produces strange results yet it is worshipped as OURS.

To many intellectuals the very word ‘liberalism’ is anathema and to the popular mind it is often associated with the political party of that name. As to the latter, set that aside. After all one can talk about labor without invoking that party, so surely one can talk about liberty without limiting it to Liberals. They do not own liberalism any more than the ALP owns the concept of labour.

As to intellectuals the story inevitably is longer though simple. The short version is the liberal-democracy has been regarded as the root of all evil for two generations. That mantra has made many a career, Think Noam Chomsky and all the little wanna-be little Noams out there, often citing incomprehensible French and German thinkers to clothe the nostrums they spout. Against that bulldozer of opinion it is a brave scholar who proclaims allegiance to liberalism. This ground has been trod in previous posts, the most extensive being on a CBC program; I forebear from repeating here not out of consideration for the bleader, but because it is too depressing to recount.

Suffice it to say that during the Cold War, complacent and secure intellectuals made it a career to attack and undermine their own society, and they did such a good job that their spawn now is the President of the Electoral College, the Twit in Chief.

Getting back to MADE, there is intellectual content. The analysis of the speeches on audio and video was very fine and well worth doing, though neither that analytic content nor the speeches themselves were integrated into the meaning of democracy. Yes, speeches can be influential. Adolf Hitler knew that, and by the way he participated in and won elections without the bedrock of liberalism. Likewise the video parade of books was well done but was not integrated into the theme of the Museum. What Thomas More’s ‘Utopia’ has to do with AUSTRALIAN democracy is anyone’s guess.

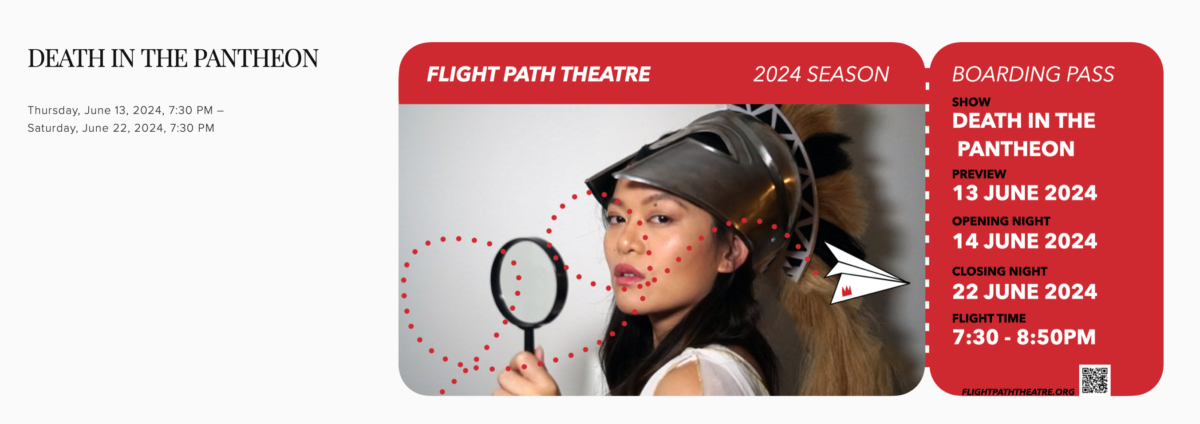

Outside is a symbolic replica of the Stockade and that is imaginative, informative, and interesting. It is located on the original site, and it gives some idea of the scale of events. Well, I assume the scale is relevant. It is small though inside the rhetoric is large.

As homework for this visit, I read Clare Wright’s ‘The Forgotten [Women] Rebels of Eureka’ (2014).

I got a lot of the context of the Victorian Gold Rush from it, which was all new to me, despite the agony of reading all six volumes of Manning Clark’s vastly overrated ‘History of Australia.’ (That Clark hatred Australia was very apparent to this reader and also that he resented the fact that he lived here.) The explosion of the population and the attendant confusion was food for thought. The population of the colony of Victoria doubled in weeks, and then doubled again, and again. The flood of gold-fevered immigrants was so great that a FULL sign went up and they were turned away from Port Phillip in Melbourne. To circumvent that prohibition passenger ships landed many in South Australia who then walked a thousand kilometres to Victoria.

Most of these feverish get-rich-quickers were young men. Half the population was under twenty-five, burning with the brassy impatience and dangerous inexperience of youth. Thousands and thousands were Chinese and this influx was one catalyst for the later White Australia policy which was born in Victoria. Many Chinese had been displaced by the aggressive British Opium Wars in southern China. (For the fraternity brothers who cut the class, the British fought the Opium Wars [plural] to force the Chinese to accept in trade British opium from Afghanistan. From this chapter of history was born the mythical Chinese Opium Den [British owned].)

The vagabonds, freebooters, refugees, gold diggers, and others who flocked to Victoria were polyglot. Some were late Forty-Niners from California, including some riff-raff thrown out of San Francisco. (Imagine what it took to get thrown out of San Francisco at that time.) French escaping the turmoil of 1848, as well as Hungarians, Jews, Croats, Italians, Venetians (who then, as now, do not regard themselves as Italians), Irish, Rutherainians, Ottomanis, and the like found passage to Victoria. Those who missed California in 1849 were not going to miss out again!

It is some indication of scale of the gold rush that these centuries later that two of Australia’s largest and most substantial inland cities were built from scratch at the time and remain, Ballarat and Bendigo. Each still evinces the wealth that abounded in their past in the scale of their streets, the monumental public architecture, the grand houses, and the art in galleries.

This human assortment at Eureka had nothing in common but gold lust. They were not Englishmen out to (re-)claim the traditional rights of Englishmen as were the American revolutionaries. They were not Europeans bent on toppling the privileged and exploitative ancien régime, though MADE draws a straight line from these uprisings to Eureka, leaving aside the pogroms the accompanied many of them. They were not intellectuals inspired by Thomas Paine’s ‘The Right of Man.’ They were greedy individualists. Period. Sorry, Chips, but it is the obvious truth. None of them was there to make a better world, serve humanity, cure cancer, or anything else, but to feather their own nests. They wanted secure property rights for individuals, not majority rule.

Here is an irony. If this human soup was the origin of Australian democracy, the practice of democracy in Australian for the subsequent century and half was partly dedicated to straining that soup. It had started earlier with the near extermination of the aboriginal population. White Australia kept out the Asians. The oppression of the Catholics kept the Irish and later Italians in their place well below stairs. The reluctant acceptance of Post World War II refugees, known as refos, from Europe was only slightly preferable to Australian democrats than the Yellow Peril from the north.

The point is that Australia was no better. albeit no worse, than other European societies.

The curator at work shows the size of the flag.

The curator at work shows the size of the flag.