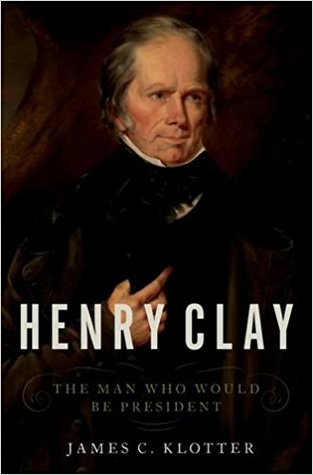

This is the completion of an excellent biography of a singular military and political leader.

When Finland created itself in 1917, Mannerheim was the man of the hour.

From the summer of 1917 to 1919 Finland was a land, with ill-defined borders, of conflict. In the textbook history, there were two overlapping wars. The Independence (sometimes Liberation) War to drive the Russians, be they Czarists or Bolsheviks, of Finland, and a Civil War between Red Finns and White Finns. These two conflicts overlapped and intwined.

White Russians wanted aid from White Finns in their own civil war in Russia, and Red Finns wanted help from the Bolsheviks in Russia in their struggles in Finland.

Greater Finland, some maps also include Estonia in this national ambition in the same way that some maps in Jakarta include all of New Guinea island as part of a Greater Indonesia.

Greater Finland, some maps also include Estonia in this national ambition in the same way that some maps in Jakarta include all of New Guinea island as part of a Greater Indonesia.

Both the Western Allies and Germany, even while at war with each other, wanted to stem the spread of Bolshevism. But the Allies did not want the Germans gaining influence in Finland. Mannerheim tried to get support from the Western Allies, but they were in no position to offer material aid in 1917.

The criss-crossing of these aspirations and allegiances is detailed in the book in a concise and lucid way. Some of the belligerents stuck to their position regardless of reality.

Mannerheim changed with the times, slowly and reluctantly, but change he did.

He did try to negotiate with White Russians on joint action to drive the Bolsheviks out St Petersburg, as he always called it, in return for which the White Russians would acknowledge Finnish sovereignty. The White Russians refused to countenance Finnish autonomy. They stuck to their guns and went down.

North is white and south is red.

North is white and south is red.

He created a Finnish Army that disarmed and expelled the Czarist garrisons in Finland, some thirty thousand of them, closed the border against the Bolsheviks, and defeated the Red Finns in a civil war by systemic and methodical action. The Red Finns had dominated Helsinki and southern Finland.

The caption says it is White solders murdering Red prisoners.

The caption says it is White solders murdering Red prisoners.

The Finnish Council wanted a speedy resolution and appealed to Germany for help, which was offered and German troops, freed from the Eastern Front by the collapse of the Czarist regime, though a state of war continued between German and Russia, were sent to Finland. This was presented to Mannerheim as a fait accompli, and he grizzled at it. He stressed that Finland had to be created by Finns, though he said that in Swedish. He also insisted that the Germans play only a supporting role.

Instead it was the Germans who defeated the Red Finns in Helsinki, and this outraged Mannerheim, but he swallowed it. It was a done deal, though it left a long and bitter aftertaste.

Then another comic opera ensued. Finland now had to have a constitution, and the self-appointed leaders decided on a monarchy and in early 1918 invited a German prince from Hesse to be king of Finland. He dickered on terms in great detail about everything from regalia, to aide-de-camps, to caviar so long that, well the German Western Front collapsed, and even the most stubborn Finns realised setting up a German in Helsinki was not a good idea. If the Prince of Hesse had not stuck to his guns he might have slipped in a Finnish throne before the fall.

For about eighteen months as the Civil War wound down, and while a new constitution was formed and then changed, the Finnish Council named Mannerhiem Regent. He was at once Commander-in-Chief of the armed force and head of state. He got the Germans out and spent a lot of time courting the Western Allies.

The war made Mannerheim a Finn as never before, but it also made him a White Finn in the eyes of Red Finns and their sympathisers and supporters in their defeat. He was polarising, even divisive figure. That would change.

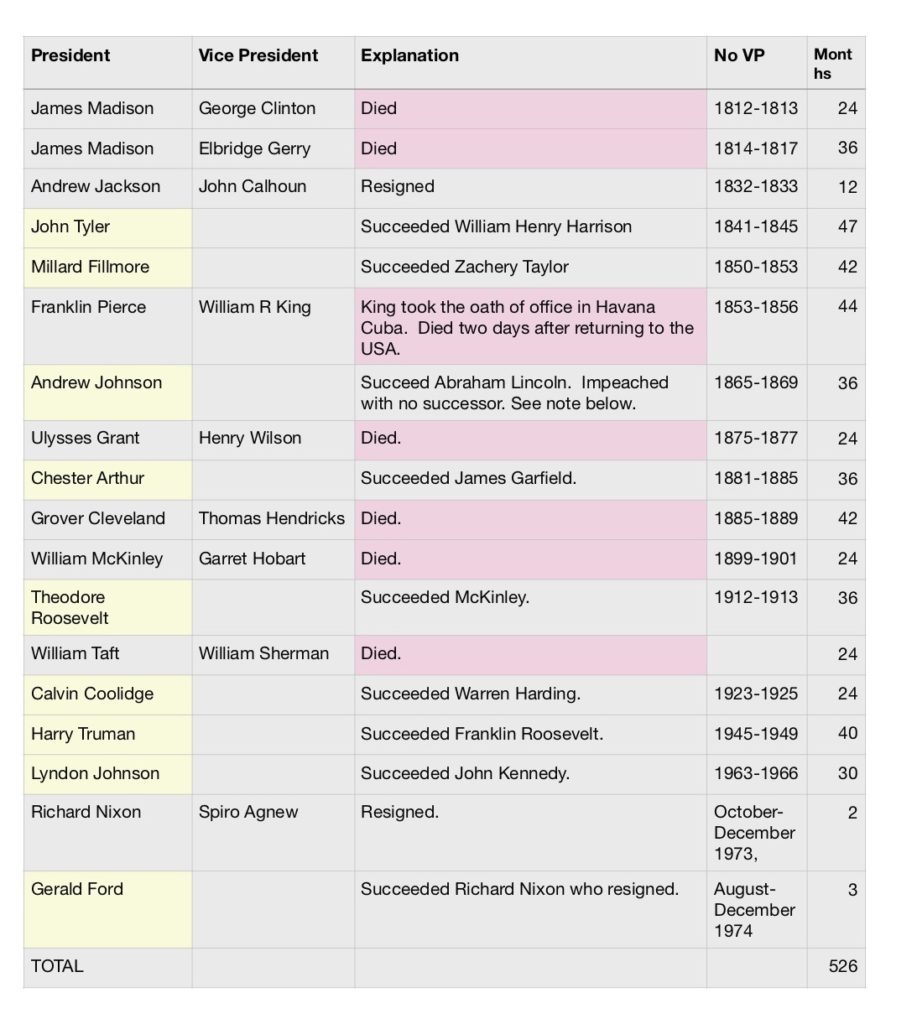

The revised constitution called for a President and a Prime Minister on the French model. The President elected and the Prime Minister the leader of a majority in the parliament. How then to elect the president. It was common for such officials to be elected by the legislature, The alternative was direct popular election. No one doubted that Mannerheim would win a popular election.

But he had many enemies in the parliament. The Agrarians of the right thought him Russian in disguise. The Liberals of the centre thought he was a Swedish coloniser. The few remaining socialists of the left hatred him because of the Civil War. The Conservatives suspected he would be a dictator. He would not win election in a parliamentary vote.

Mannerheim recognised the election of the first president in the new, sovereign constitution was a very important event for the future harmony and stability of the country and so in the interest of stability he accepted a parliamentary vote without argument. In due course, he was a candidate and lost decisively. Think of Churchill in July 1945 losing.

From 1920 to 1932 he was a private citizen, if a former supreme commander and head of state can be that. He traveled in Europe and became an unofficial representative of Finland, much to the annoyance of the foreign minister in Helsinki. His aim was to affirm Finland’s sovereignty, and win it friends and support in Western Europe against the tides of the future.

In Finland he remained a popular figure in the public mind, apart from socialists; his political enemies, the full spectrum from left to right, blackened his name at any and all opportunities. This was another reason to travel abroad.

Thanks to the influence of his sister, Sophie, when he retuned to Helsinki, he threw himself into good works and became president of the Finnish Red Cross where he was not content to be a figurehead on the letterhead. Instead he developed training and recruitment. He also strove to raise money and succeeded.

Then in the 1930s the political leadership realised that the League of Nations’ collective security would not protect Finland from the predators, especially the Soviet Union which had reactivated the Czarists claims to the whole country. Mannerheim was made chief of defence in a convoluted arrangement that was neither military nor political, but a little of both. In effect, he was chairman of a defence advisory committee. He was appointed head of the national militia, not the army. There followed another comic opera.

Was he entitled to a uniform? If so what kind? When could he wear it? And so and on. All of this had to be decided by a committee. He wanted symbols of office and others wanted to deny him those appurtenances. Meanwhile, the Soviets built roads to the border, dredged anchorages on the coastal approaches to Finland, flew over Finnish air space to photograph the ground, and so on, while in Helsinki they argued about tailoring. And to the south Hitler was arming Germany with bellicose claims about the oneness of Nordic peoples and threats to Danzig on the Baltic. While in Helsinki they argued about tailoring.

The impasse was broken when the national militia declared Mannerheim an honourary field marshal and presented him with a baton of command. This presentation was widely publicised because Mannerheim had learned to use the press, while his enemies had not. In the end, the parliament, begrudgingly, made him a field marshal of the regular army. But he only and always carried the first baton bestowed on him by soldiers, not parliamentarians.

He became a one-man lobby for increased defence spending, conscription, training, fortifications, aircraft, warships, a medical corps, and so on. He invited newspaper editors to dinners and argued his case with them. He also tried hard to secure an alliance with England and France and when that receded, he then tried for a Nordic defence pact but Sweden would not jeopardise its neutrality, on the assumption that the Russian bear would be content to eat Finland.

He also made an effort to learn Finnish. He had dabbled at this for years without systematic application. He selected two aide-de-camps who spoke only Finnish, and that meant he had to speak Finnish to them, to get a file, to get a match for a cigarette, to bring the car around for trip, to telephone newspaper editors…… He also hired a tutor who worked with him an hour every night. Then there were small dinner parties of four or five Finnish-speakers. These were not business meetings, not were they pleasure, but rather language practica. When this man decided to do something, he did it. In a few years he could speak enough Finnish to give speeches broadcast on radio, and read it, but he could never quite write it properly and retained an assistant especially for that purpose.

When he began inspecting troops, and interviewing field officers, he had cue cards in his pockets to remind himself what to say and how to say it.

Even in 1938 there were parliamentarians who assumed there would be no war that would involve Finland. Wrong! The Baltic Sea would be a prime battleground as Mannerheim saw it. That is one reason why he courted England with the Royal Navy.

The Soviet offensive.

The Soviet offensive.

Perhaps Mannheim’s most decisive achievement before the Winter War was to change the method of mobilisation. Instead of gathering troops at a few central points, arming them, and then transporting them to the front he changed the locus of organisation to many local levels and distributed the arms and accoutrements of war to warehouses throughout the east parts of the county. Mobilisation would them involve much less transportation, though it dispersed control.

When the Soviet attacked, Finns responded much more quickly thanks to this dispersal of men and armaments. It also left much more leeway for local commanders to use their own judgement, which many did to good effect. He had also implemented a training program for these local commanders to learn the best exercise of that judgement.

Finnish troops using reindeer as beasts of burden.

Finnish troops using reindeer as beasts of burden.

Though Mannerheim knew that details mattered, he never seems to have been a micro-manager.

The Winter War started in November 1939 while Germany and the Soviet Union were dividing up Poland. The Soviets had strategic and historic reasons to attack and they arranged a pretext, taking a page from Hitler’s Poland book. In the first phrase about 400.000 Soviet troops attacked about 150,000 Finns.

The Soviets were better equipped and that became a liability. their heavy tanks and trucks had to use roads through the forests or cross frozen waters. The Finns used those passages as choke points. Most of the Soviet effort was around Leningrad but there was also a strike above the Arctic Circle. This first Soviet offensive failed with terrible losses.

Stalin reacted as Stalin did. He murdered scores of Soviet generals, and formed a new offensive on an even larger scale. Soviet manpower in the army was unlimited compared to Finland. The second offensive included 600,000 troops.

The Finns resisted along the so-called Mannerheim Line in the South. It was nothing like the Maginot Line, representing the places where geography favoured the Finnish defence in the forests and lakes. Elsewhere the white-clad Finns concentrated on behind the lines raids to harass, slow, and deflect the invaders.

Resistance was futile, and many efforts to secure weapons and support from the West and Scandinavia failed. The Soviets offered negotiations, perhaps realising that to vanquish Finland might lead to a military clash with either Germany in Norway, or even the Western Allies.

Field Marshall Mannheim at his desk in early 1944.

Field Marshall Mannheim at his desk in early 1944.

Mannerheim strove to hold onto Finnish territory until spring thaws would clog roads and melt ice, which together would immobilise the Soviets. The spring was late, and the Treaty of Moscow was concluded in April 1940 on very hard terms. Perhaps 20% of Finland would annexed by the victors, and its population relocated to the rump of Finland. Financial reparations were exacted, paid for mostly by metals and minerals and control of Baltic islands. This might well have been the first bite, with another to follow.

A kind of peace ensued. Mannerheim had been made Commander-in-Chief of all arms during the war and that authority rolled on. His sway with the parliament was great now, because so many of them had been discredited for supposing no war would come, for cutting defence budgets, for not denouncing the Soviet Union earlier enough and loud enough, and for fleeing while the army fought on.

The Finnish national day had been heretofore the day that marked that the end of civil war. To the Reds of Finland that was a day of ignominy. Mannerheim changed the national day to coincide with the defeat in the Winter War. He saw in the months of the Winter War, as did nearly all others, one Finland, neither White nor Red.

If Finland made itself a geo-political entity — a state — in 1917, in 1940 the Soviet made Finland socially into one people — a nation.

From mid-1940, as World War II unfolded, Mannerheim assumed that the two colossi would clash and the Finland would be in the middle. While he did not favour an alliance with Germany, which was on offer, there would now never be any reconciliation with the Soviet Union. The Western Allies were too far away, and France was out of the war, and could not be counted on for support.

Once again he prepared Finland for the next war. Only locally made equipment could be had, but the army was doubled in size.

In the weeks before Operation Barbarossa, the Germans made demands on Finland for passage from far northern Norway to Russia, and the Finns agreed.

The Germans were so intent on practical matters, that they did not press the Finns for a formal alliance. The Finns, for their part, agreed to fight the Soviet, but only if the Soviet first attacked Finland. When the Germans invaded the Soviet Union, the Finns held their positions and waited. Sure enough a few days in the battle and the Soviets began bombing and shelling Finnish territory and the Finns became co-belligerants.

It is a technical point that later was of paramount importance.

The Germans had offered Mannerheim supreme command of all troops in Finland, German and Finn. He declined. That would have brought 250,000 German combat troops from the Arctic Circle to the Baltic Sea under his command, along with the 650,000 Finns in uniform. However that would also have made him subordinate of German High Command in Berlin, and he wanted scope to act independently in the interest of Finland, not as ordered from Berlin.

As much as 20% of the Finnish population was in uniform, including scores of thousands of women. It was prodigious national effort that could not be sustained long.

His prudence also meant that he directed the Finnish war effort at strategic targets rather than symbolic ones. Ergo the Finnish advances cut-off Leningrad from the north but did not directly attack Leningrad. Another fine point that later proved crucial. He assumed no subsequent government in Russia would forgive or forget an attack on that city so the Finns would not attack it.

To stress the Finnish nature of the conflict, Finns called it the Continuation War, the war that continued the Winter War. Every effort was made to keep it separate from the German war so that Finnish interest were seen as separate. Finland was divided into a northern and southern zones and the Germans in Lapland had the north. That meant that when the Germans attacked in the north the Finns did not support it. Rather they held their defensive positions much to the outrage of the Germans.

It was widely assumed in 1941 that Germany would knock the Soviet Union out of the war just as it had done in 1917, either directly or by precipitating a regime change.

The Finns in the south advanced to the 1939 border and stopped there and remained on the defensive. In the north the Germans were unable to cut the Murmansk railroad, and that failure registered with Mannerheim. The stout Soviet defence of Murmansk and the railroad led him to conclude that the Soviet regime would not be knocked out, nor would the regime topple.

Thereafter the prospect of a separate peace with the Soviet Union was discussed among Finns.

Hitler wanted to draw Finland closer as his Soviet invasion faltered, and a Fuhrer-visit was proposed.

Hitler and Mannerheim deep in the north woods.

Hitler and Mannerheim deep in the north woods.

Mannerhein advised the government against it, and himself stalled. Finally it was agreed that Hitler would attend Mannerheim’s 75th birthday lunch. On the grounds that he could not leave the front, this was held in a forest in east Finland with few guests and no media, apart from the offical photographers.

Instead of state visit in Helsinki with parades, flowers, presentations, speeches there was a two-hour lunch followed by coffee with a few candid photographs.

Inevitably, as we now know, the Soviet Union attacked Finland in 1944 with a numerical advantage of ten to one, and the front crumbled. The Finns fell back to the second line, to the third line…. Mannerheim told the government that one more push from the Soviets and it was over.

However, the push did not come. Instead Soviet troops transferred south to concentrate on the advance on Germany, while Finland imploded.

Any effort at a separate peace would invite German retaliation, but with no separate peace the Soviets would sooner or later attack again. To walk this fine line the parliamentarians, who were on a carousel by this time, changing governments weekly, proposed uniting civil and military power in Mannerheim. He declined several times but finally agreed and the parliament made him president while he retained the role of commander-in-chief of the armed forces and Marshal of Finland. The feeling was that only Mannerheim had the domestic moral authority to convince the populace to comply but not to lose hope. That only he had the authority to convince the Germans that Finland was serious about leaving war, and the Soviets that it would honour an agreement.

He set about securing a separate peace and preparing for conflict with the Germans. While Finland was a co-belligerent, Germany had been supplying much fuel, war material, and food. Once the rumour of a separate peace circulated these supplies stopped. In anticipation of just such a reaction Mannerheim had been stockpiling supplies for about a month beforehand.

The Soviet demands were territorial, financial, and moral. They wanted back east Karelia and to move the boundary on the Karelian isthmus north, huge reparations, and a treaty of friendship of the kind it had had with Estonia. (Gulp!) The Finns conceded the territory and the reparations but bargained away the treaty in favour of guarantees of neutrality. It was a return to the 1940 post-Winter War borders with a financial burden on top.

It may seem to have been wasted effort, but there was no third way for Finland. Had it not entered the war, the Soviets would likely have occupied the whole country to control the Baltic, and stayed. Sweden was far enough away to be neutral, but Finland was not. Had the Finns not entered the war, the Germans might have occupied the whole country and set up a puppet regime as it had done elsewhere, and used Finnish resources for German ends.

Finland was the only associate of either German or the Soviet Union to keep its independence and to continue its internal way of life, e.g., parliamentary democracy and religious freedom. Despite pressure Jews were not deported. Indeed Mannheim attended a memorial in a synagogue in Helsinki for fallen Jewish soldiers in the Finnish army, a fact reported in the local press.

In addition to the other terms, the Soviets also wanted the Finns to expel the German army in the North, some 250,000 Alpine troops around the Arctic Circle besieging Murmansk. This led to another conflict, called in Finnish history, the Lapland War. The exhausted, defeated, undermanned, ill-equipped Finnish army turned north to push the Germans back into Norway at the behest of the Soviets. While this was a low level conflict compared to what was going on elsewhere, another one thousand Finnish soldiers were killed.

This tumultuous period in sum:

Winter War April 1939 – May 1940

Interim Peace 1940 – 1941

Continuation War June 1941 – April 1944

Moscow truce 1944 ended Continuation War

Lapland War April 1944 – May 1945

Peace 1945

The War of Liberation, the War of Independence, the Finnish Civil War 1917-1919 made the geographic entity Finland. However it was the Winter War together with the Continuation War that made Finns into a single people. The national unity, especially in the Continuation War was palpable, and Mannerheim did everything he could to nurture and encourage it. He ended the celebrations and symbols of the Civil War, and created instead public holidays, awards, and recognition for contributions to these two later wars with the Soviet Union.

With the end of the Continuation War a Soviet Control Commission set up in Helsinki and intervened deeply into Finnish politics, society, and economy, but not as deeply as in the Baltic, eastern, or central Europe. There was no puppet government and sometimes negotiation was possible. But parliamentary candidates, court appointments, factory rebuilding, and more all had to be approved by the Soviet Control Commission, which in turn referred decisions to Moscow. The Soviets ensured that Finland did not receive aid from the Marshall Plan.

In 1948 many Finns, including Mannerheim assumed a communist putsch would occur in Helsinki as it had in Prague. He burned many archival papers at the time, and army officers cached weapons in anticipation of another, guerrilla war.

Mannerheim resigned as domestic politics went back to the old ways of backstabbing and undermining, much of it encouraged by the Soviet Control Commission which preferred disunity. His health was deteriorating and he spent time in Portugal and Switzerland, where he secretly worked on his memoirs. In the memoirs he tried to set the record straight, as he recalled it.

He died in 1951 at age 84. Even in death he polarised the society. Some wanted a state funeral and others opposed it, believe it or not. The army pretty much forced the issue and it was a state funeral which was boycotted by the communists in parliament.

Equestrian statue of Mannerheim in Helsinki.

Equestrian statue of Mannerheim in Helsinki.

On 5 December 2004, Mannerheim was voted the greatest Finnish person of all time in the Suuret suomalaiset (Great Finns) contest.

There were twenty years between the first and second volume, yet the level of analysis, handling of sources, expression are continuous. Well done.

The book is a model of economy, presenting vast amounts of information in a few pages. Would the other authors would do likewise. This volume is a mere 250 pages but each is fully loaded.

Perón always kept dogs and could be seen walking them in Madrid.

Perón always kept dogs and could be seen walking them in Madrid. Eloy Martinez

Eloy Martinez

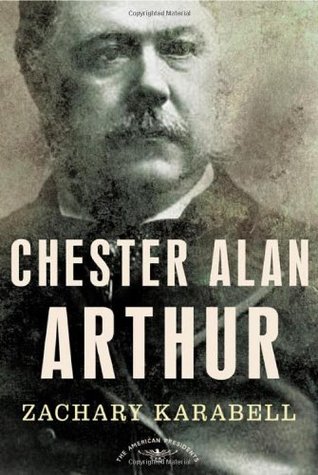

Roscoe Conkling

Roscoe Conkling James Blaine

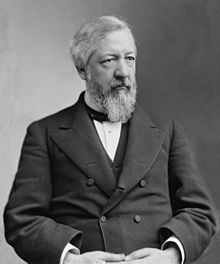

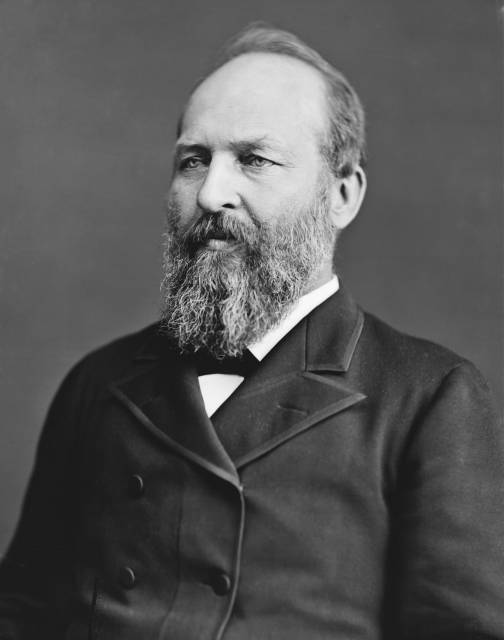

James Blaine James Garfield

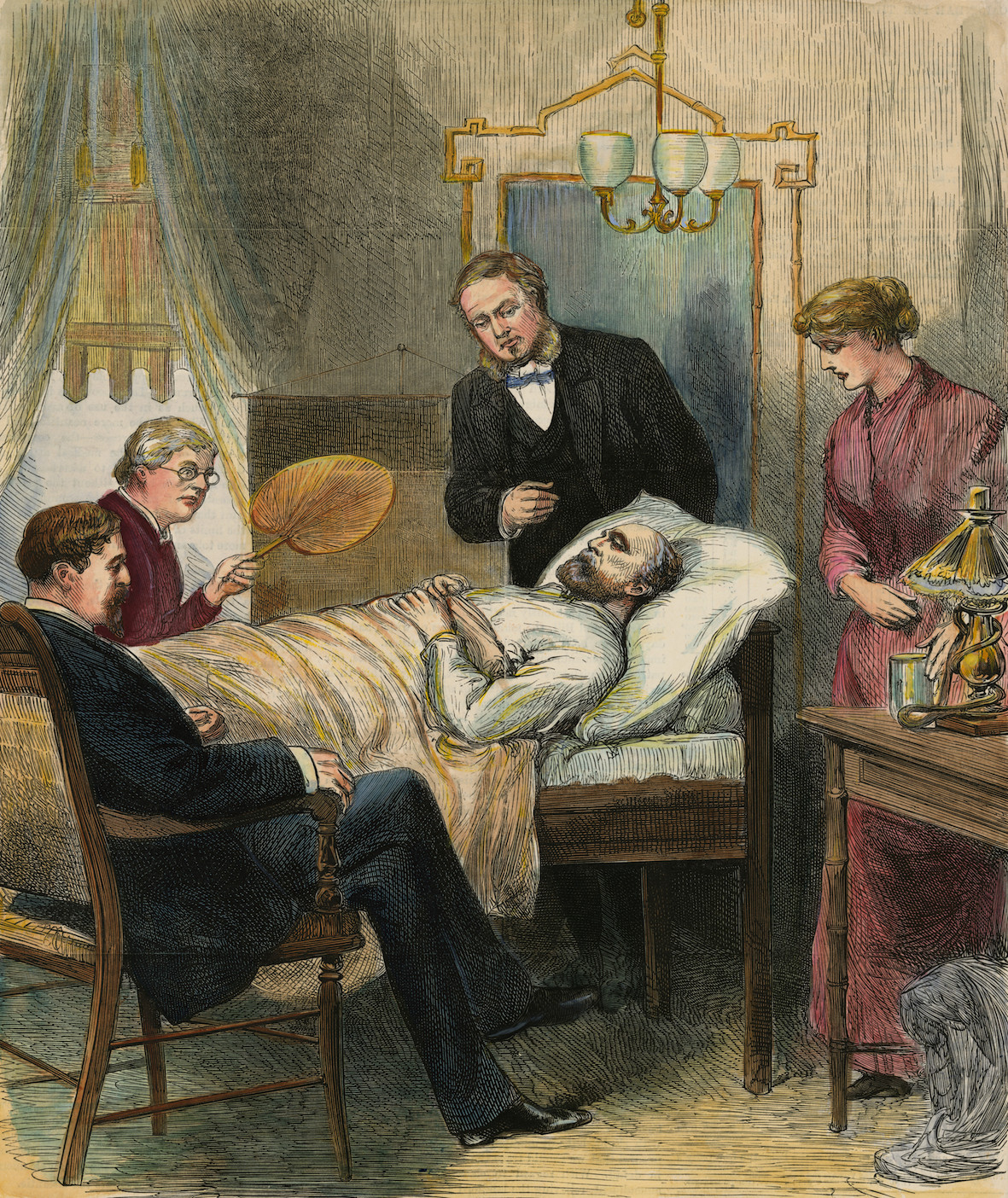

James Garfield Garfield, wounded.

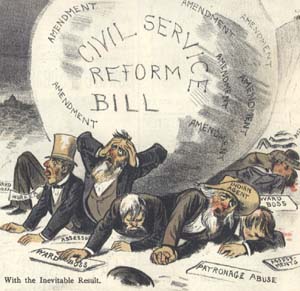

Garfield, wounded. An example of a Tiffany screen like one installed in the White House.

An example of a Tiffany screen like one installed in the White House.

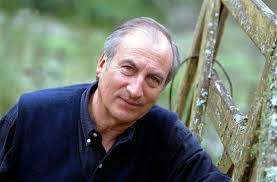

Zachary Karabell

Zachary Karabell

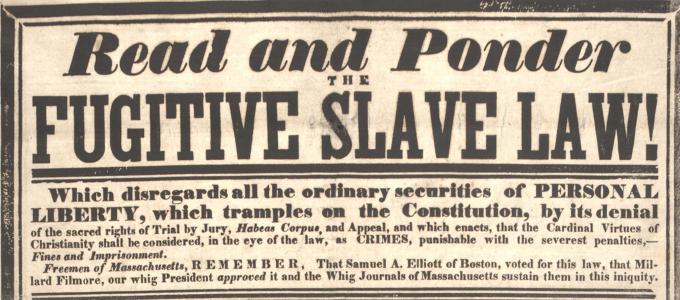

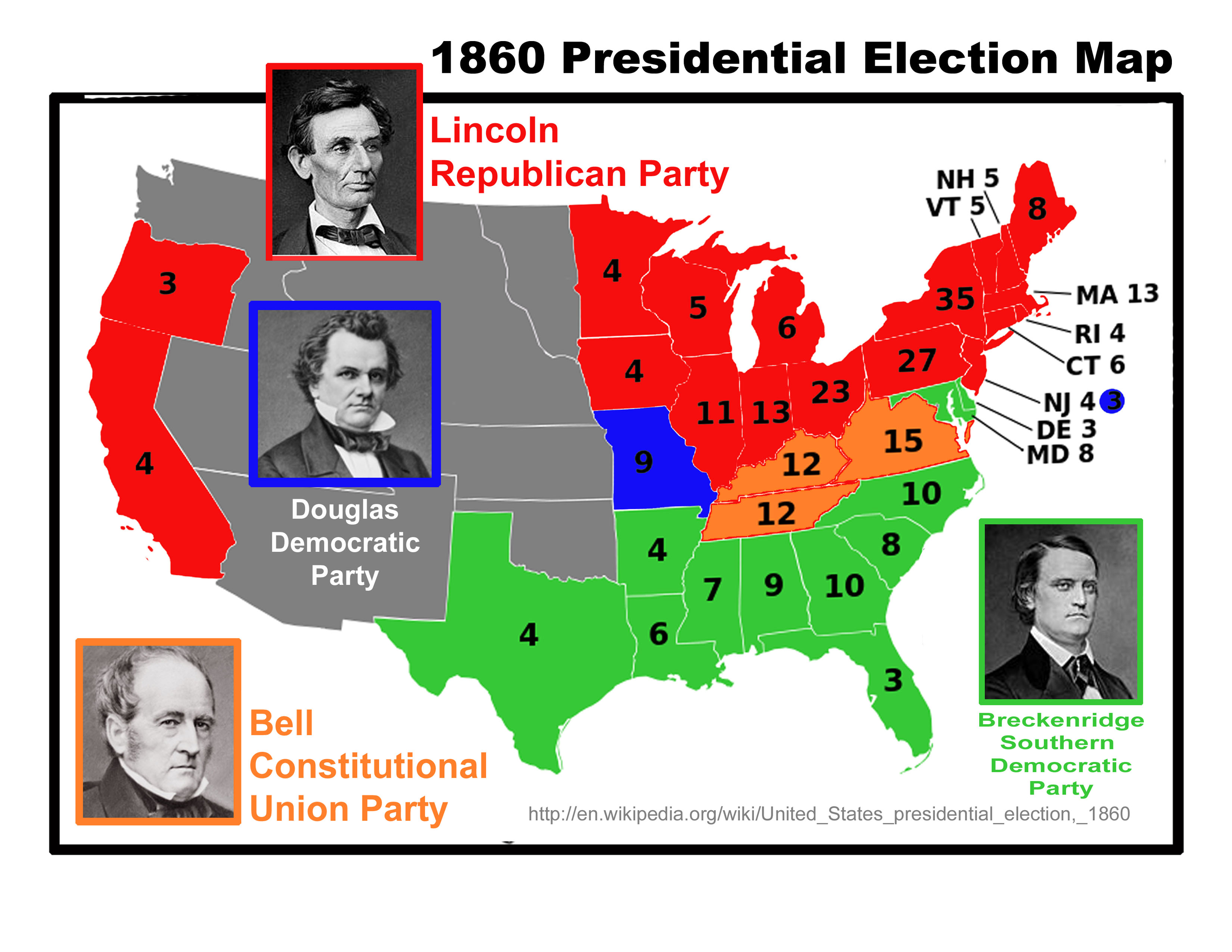

The Unorganised Territory was called Nebraska.

The Unorganised Territory was called Nebraska. Michael Holt

Michael Holt

Greater Finland, some maps also include Estonia in this national ambition in the same way that some maps in Jakarta include all of New Guinea island as part of a Greater Indonesia.

Greater Finland, some maps also include Estonia in this national ambition in the same way that some maps in Jakarta include all of New Guinea island as part of a Greater Indonesia. North is white and south is red.

North is white and south is red. The caption says it is White solders murdering Red prisoners.

The caption says it is White solders murdering Red prisoners. The Soviet offensive.

The Soviet offensive. Finnish troops using reindeer as beasts of burden.

Finnish troops using reindeer as beasts of burden. Field Marshall Mannheim at his desk in early 1944.

Field Marshall Mannheim at his desk in early 1944. Hitler and Mannerheim deep in the north woods.

Hitler and Mannerheim deep in the north woods. Equestrian statue of Mannerheim in Helsinki.

Equestrian statue of Mannerheim in Helsinki.

Now part of the US Virgin Islands.

Now part of the US Virgin Islands. Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton Aaron Burr, one time Vice President who murdered Hamilton and was later tried for treason at the order of Thomas Jefferson.

Aaron Burr, one time Vice President who murdered Hamilton and was later tried for treason at the order of Thomas Jefferson. Willard Randall

Willard Randall

William C. Davis

William C. Davis