John C. Breckinridge (1821-1875) was born to very comfortable circumstances in Kentucky. He was educated at the College of New Jersey (Princeton) where his father had many family members. Upon his return to Lexington, the young John Breckinridge went west to make his name and fortune to Burlington of the Iowa Territory where he was a lawyer to whom professional success came but slowly. Thus he spent formative years outside the slave-holding South.

He was erect, tall, courtly, well-spoken and thus invited to speak at a 4th of July occasion, where he struck the right note and that earned him both more speaking engagements and clients. His law partner, much like that of Abraham Lincoln, complained of Breckinridge spending too much time politicking and not enough lawyering.

By the way, one reason why the young Breckinridge found it easy to leave Lexington Kentucky for Iowa was that a girlfriend jilted him, she being one Mary Todd, later to wed the aforementioned Lincoln.

Though slavery was the issue that governed his life and everyone else’s at the time, he apparently had no particular opinions about it, one way or another. While he was not slaver, he did not oppose it. On every occasion he always sided, ultimately and if sometimes reluctantly, with the slave states on Lockean grounds of the absolute right of property. By the way, religion does not figure much in his life as told in these pages.

Breckinridge returned to Kentucky, the Iowa excursion had always been intended to be limited, and had more success, professional, political, and social in the Bluegrass State. His public speaking on patriotic occasions made his name known.

He served in the Mexican War, where he showed concern for the troops in his command, and learned the need for staff work to secure supplies, food, harnesses, boots, forage for animals, and medicine. These lessons he would use later in life. He also met the whole gamut of officers who would later figure in the Civil War. The list is too long to repeat here, but it included Hiram Grant and Robert Lee.

While in Mexico he defended an officer falsely accused of crimes. The accusation was hatched as a way to undermine the general commanding, Winfield Scott, whose presidential ambitions were plain to see. This was in hindsight a political conspiracy to hamper Scott’s presidential ambitions. But Breckinridge seems to a have taken it at face value. His defence was finely judged and widely reported and successful, giving him a national profile.

His service in Mexico was after the hostilities had ceased but before the treaty was signed, ceding California and New Mexico. Ergo there were still tensions and alarms, but not cannon fire. Unlike all those other Civil War generals, he did not attend West Point, and later learned to be a general on the job.

In the late 1840s and 1850s the Whig Party was destroying itself by infighting, and Breckinridge aligned himself with the rising Democrats. He vigorously campaigned for others, and in time won a seat in the Frankfort legislature. His public speaking is much emphasised. In these speeches he always took a positive tone and spoke about what was necessary, what he could and would do, and made it a point not to disparage his opponent(s). My, my that is lost art, emphasis on the positive.

When Abraham Lincoln visited his Todd in-laws in Kentucky, he met Breckenridge and thereafter they had an occasional correspondence, e.g., when one won a case reported in the press, the other would sent a note of congratulations.

As the Great Compromiser — Henry Clay, a Whig — lost his grip on Kentucky, growing old and frail, and because his party was eating itself, Democrats filled in the spaces available. Became of his attractive personality and eloquence, Breckenridge was pushed to the front. Clay seems almost to have endorsed him, despite the party differences, for they were often seen together.

In the state legislature Breckinridge was a dynamo for local improvements, from schools, roads, bridges, streets, public buildings, and so on. His staff work in Mexico had taught him the importance of detail and he applied this lesson in the legislature, while many others were satisfied with oratory, and though he was exceptionally good at that, he went beyond it to get the details right.

He married but his wife and family seldom figure in this account.

Unusual for the time, he had lived in New Jersey while in college, Iowa as a young lawyer, and being personable, attractive, and sociable, he made friends where he went and keep in touch by mail. His army service added to his contacts and gave him national publicity. As a budding Congressman, both Henry Clay and Stephen Douglas saw great things in him and said so. He campaigned for others in surrounding states.

As a state Legislator and later as a Congressman, he was a mediator. Where there was a deep divide, while keeping his own counsel, he was trusted by all to understand their positions, if not agree with them, and he would confer widely in search of some common ground.

There was only one issue: slavery, masked by states rights and the Constitution. Breckenridge played a key role in the Kansas-Nebraska Act. However much or little common ground Breckenridge could find in the wording of this resolution or that, it was never enough to paper-over the chasm of slavery.

He campaigned hard for Franklin Pierce in 1852, speaking three or four times a day in five states. While his speeches praised the Democrats, he did not belittle nor insult opponents, and generally struck a positive note, which increased the invitations to speak.

Pierce, whatever his merits, became the first, perhaps the only, incumbent president to try and to fail to secure re-nomination by his party. Though Breckinridge supported Pierce for re-nomination, when Pierce was eliminated, Breckinridge turned the eventual nominee, James Buchanan of Pennsylvania, who wanted a southerner on the ticket and one who was presentable to all regions, ego he tapped Breckinridge, though the two had nothing in common and had met but once, briefly. (Pierce never forgave him this switch, though Pierce had no chance of renomination.)

In those days the candidates retired to their homes and did not campaign, leaving that to others, and from this practice party organisations emerged. ‘Buck and Breck’ won for the Democrats.

Breckinridge had the same relationship to President Buchanan that all Vice-Presidents have with all Presidents. None.

Though the country was boiling with dissension and the parties were cracking along geographic lines for the first times, the Pennsylvanian Buchanan did not ask the Kentuckian Breckinridge to attend cabinet meetings. Indeed they had exactly one private meeting and that was in the last year of their term about a triviality.

Buchanan was unmarried and solitary by nature. Accordingly, he delegated ceremonial and social tasks to Vice-President Breckinridge, e.g. receiving ambassadors, hosting functions, addressing celebrations, all of which expanded Breckinridge’s horizons and networks.

His main duty was to chair the Senate and he did this scrupulously, unlike most of his predecessors. He was impartial in the chair during heated and intensely partisan debates, but more importantly he spent much time talking to senators before the debates so that he knew what to expect. Ever the mediator, he often was a go-between used by factions and parties to communicate with each other and at times he found that undiscovered country. – common ground to smooth over the crisis de jour. Even that most stalwart and violent Republican, William Henry Seward praised Breckinridge’s management of the fractious Senate for four years. It may be the only time Seward even publicly said a good word about anyone.

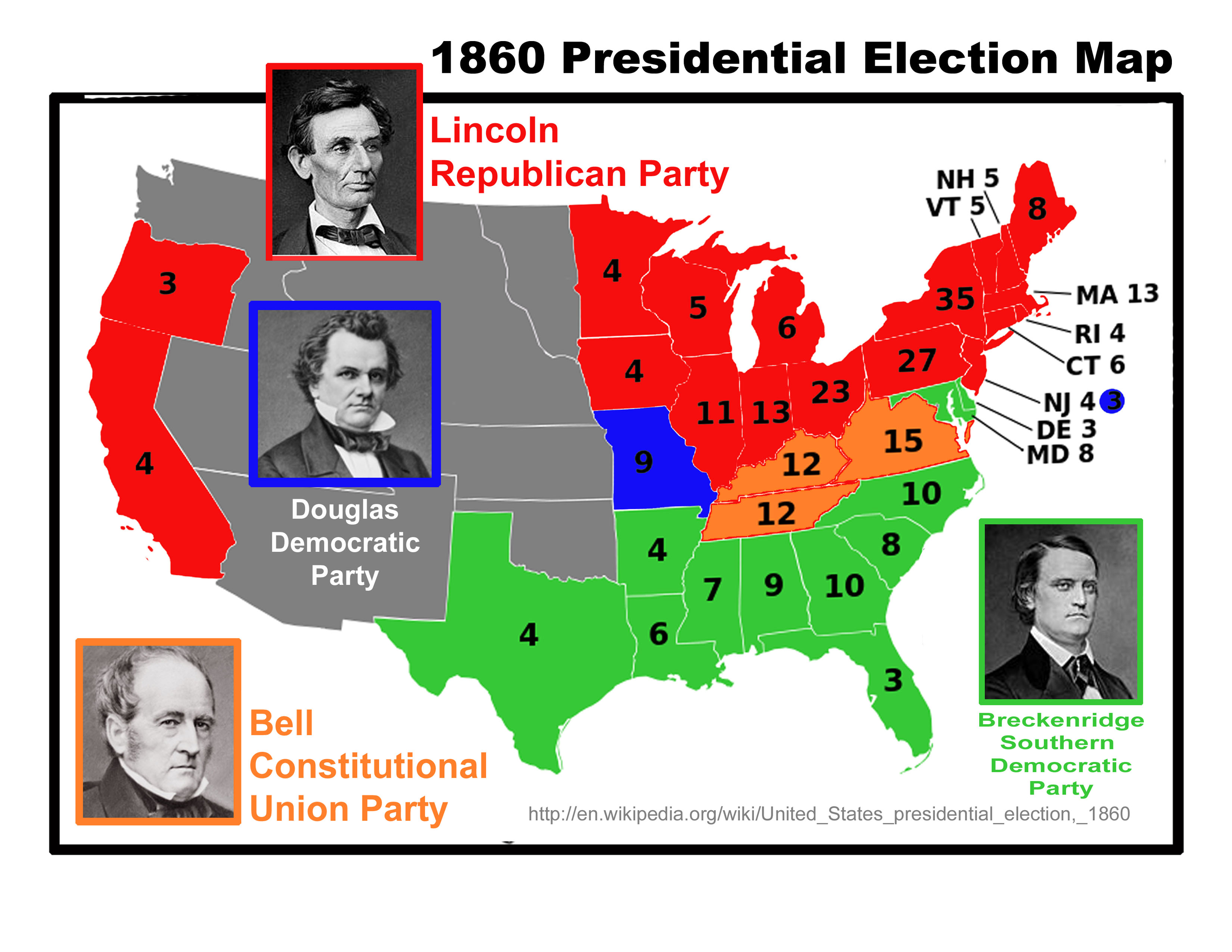

The machinations of the 1860 election are many. The Republicans put up an obscure western lawyer named Abraham Lincoln. The Democrats split along the geographic fault line of Mason-Dixon with Stephen Douglas as the northern Democrat candidate whom southern Democrats distrusted. John Bell became a third party candidate appealing for national unity in the border states like Kentucky, Delaware, Maryland, and Missouri. Southern Democrats nominated Breckinridge, and he accepted. But why?

Splitting the anti-Republican vote would insure that Lincoln was elected, and Breckinridge accepted the nomination precisely to avoid that split. How so? Pay attention now, class, this is today’s lesson.

Once Breckinridge was in the field, the hope was that Douglas would realise he could not win. Then the three candidates — Douglas, Breckinridge, and Bell — would meet and agree to withdraw in favour of another candidate and several were lined up, or the other two would withdraw in favour of Breckinridge. Note that Breckinridge did not seek the nomination in the first instance thinking it was inconsistent with his duties as Vice-President. Odd that. But he was certainly flattered to be nominated.

This plan never flew. Douglas made it clear that he would not withdraw and the four-way race ensued. By then it was too late for Breckenridge to withdraw.

The author makes a good point when he lists those who voted for Breckinridge, which include Robert Lee, Hiram Grant, Jefferson Davis, and Benjamin Butler. The point is that Breckinridge was a national candidate, as well as a regional one. He got votes in Massachusetts, Ohio, Virginia, and Tennessee. But it is also true that his vote was concentrated in the South and he carried all the slave state and Delaware, apart from Tennessee, Virginia (both taken by Bell). and Kentucky (ironic that, and shades of Al Gore) which also went to Bell. (Despite 30% of the total vote, Douglas won a majority only in Missouri.)

As the sitting Vice-President he organised the inauguration of Lincoln. He had won election to the Senate and while other southerners left as soon as Lincoln won in November 1960, he stayed after Fort Sumter in April 1861 and even after Manasses in June 1961. He was trying to calm things down but he gave up.

Meanwhile, Kentucky, divided between unionists and secessionists, tried to be neutral as the war started. But eventually Grant’s army crossed the Ohio River to Paducah, and in response a Confederate army entered eastern Kentucky. Breckinridge then returned to Lexington and accepted a commission from the secessionist governor in the state militia. Quite why he went grey and not blue is not very clear. Most of his relatives were secessionists, but not all, but in confusing times that is what he did, and once comitted he stuck it out.

He was now the soldier of the subtitle. He learned on the job, and learned quickly, but he did make mistakes. Braxton Bragg hated him, but Bragg hated just about every other officer in the army.

He served in a variety of places, including Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia, West Virginia. He took part in General Jubal Early’s 1864 raid on Washington DC and his troops shelled Fort Stevens while Abraham Lincoln watched from the ramparts, those two presidential candidates meeting again at this distance during a barrage.

In desperation, President Davis appointed him Secretary of War in early 1865, and he became a statesman again. This part of his career is the subject of another book reviewed elsewhere on this blog, namely ‘An Honourable Defeat.’ Here it suffices to say that it was his finest hour. He did much to bring a lasting peace.

His health was broken by the war years, and when he returned to Kentucky he eschewed public life, refusing even President Grant’s suggestion that he re-enter political life. But he became a symbol of one who accepted the defeat and looked to the future.

William C. Davis

William C. Davis

The book is meticulous and informative. The last chapter offers a very good summary and judgement of Breckinridge’s careers as statesman, soldier, and symbol of the Confederacy best elements.

Skip to content