The last days of a regime.

Regimes come and go. In most places in the world the change is rocky, ragged, and rugged: Mubarak in Egypt, Allende in Chile, Hitler in Germany, Amin in Uganda, Franco in Spain, or Peron in Argentina. Mobs in the streets, armed police off the leash, fires breaking out here and there, hastily packed bags, the Swiss account numbers memorised. It is even more difficult when there is a war on with marauding raids, artillery shells in the air, and masses of troops on the move.

That is the subject of this book, the transition of the government of the Confederate States of America out of existence from February 1865. The hour finds the man, Italians sometimes say, and this hour found John C. Breckinridge who is the major character in this telling.

An honourable defeat, as in the title, would mean the best possible negotiated terms for the men of the Confederate Army and Navy, e.g., that they would be allowed to go home and not be imprisoned or otherwise punished and also that civil order would continue even when the war ended, i.e., that the state governments would continue to maintain law and order, protect banks and private property, dams, bridges, roads and so on. None of this could be assumed, it had to be brought about…somehow. It also meant that the army would not disintegrate into bands of armed men preying on the civilian population.

An honourable defeat also meant that none of the tens of thousands of armed men pledged to the Confederacy would be encouraged by word, deed, or silence to resort to partisan or guerrilla warfare. That is. when the government capitulated, all its loyalists would lay down their arms. There would be no further resistance.

In return for that guarantee there would be no reprisals against individuals. Breckinridge also wanted the units of the army to remain together and march home, i.e., the Fifth Mississippi infantry regiment would march back to Mississippi en bloc and put themselves under the authority of the state government as a militia to keep order, if that were necessary, and the looting and banditry that occurred in Richmond and environs so quickly after Lee’s withdrawal made this a real possibility. Indeed if the units simply broke up individually, the fear was that some would turn to banditry, think of the James brothers. Even those who called themselves partisans would be a greater threat to Confederate civilians than to the Union army, e.g., the James brothers when they rode with William Quantrell.

To bring about an honourable peace was difficult, first, because the elected president of the constitutional government of the Confederate States, Jefferson Davis, did not accept defeat was inevitable. Second feelings ran high after years of death and destruction, would anyone listen. Third, getting any message out was nearly impossible given the destruction of railroad and telegraph lines.

A major part of this story is the intransigence of President Davis for whom every reverse meant only that others had to redouble their efforts and make more sacrifices. Under the blows of defeat, he increasing retreated into a silent shell, but when he did speak it was the same message of more effort, more sacrifice. Even when resistance would serve no purpose he would not accept the personal humiliation of defeat, at the cost of the lives of many others.

During most of the flight of the Confederate government from 2 April to the end of May, Davis was lost in a cloud of despair and denial, leaving Breckinridge to exercise the executive powers remaining to the government. These powers were few but they were not negligible for those affected by them. Chief of these was to maintain social order, but also extended the preservation of and then the orderly disposition of government property. He was de facto acting President.

President Abraham Lincoln had refused to recognise the Confederate Government and he would never treat with it in any way. Yet Lincoln’s murder changed everything, for the worse, and meant that the Federal government was even less likely to respond to any overture from the Confederacy.

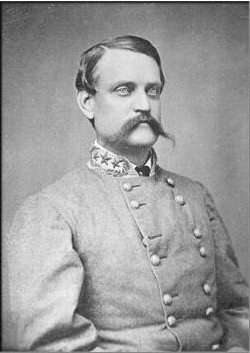

That the result was as peaceful, harmonious, and orderly as it was, the author credits largely to the efforts of John C. Breckinridge (1821-1875). He was a moderate from Kentucky with a distinguished political and military career. After a term in the United States Senate he was Vice-President in the administration James Buchanan (1857-1861). He was a candidate in the 1860 presidential election, one of four, and he won most of the Southern states, and so had a national reputation. After the election, won by Abraham Lincoln with far less than a majority of votes, Breckinridge returned briefly to the United States Senate.

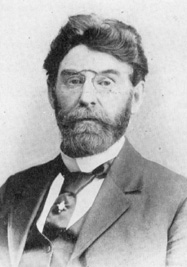

John C. Breckenridge

John C. Breckenridge

He had served in the Mexican-American War of 1846-1847, as did so many other Civil War soldiers did. When the Civil War loomed he was commissioned a brigadier general to raise Confederate troops in Kentucky where his family name was widely respected. During the war he rose in rank to major-general of the CSA and served at Shiloh, Stone River, Missionary Ridge, and New Market. Like everyone who had to misfortune to serve with Braxton Bragg, he was sidelined because Bragg, being one of the few with any influence over Jefferson Davis, convinced Davis that Breckinridge was disloyal. Go figure, after reading that list of battles.

Despite being in sole command at one of the few battles Confederate arms won in 1864 at New Market, he was relieved of command. Then in a desperation move, Davis appointed him Secretary of War. It was desperation because no one else wanted or would take the job, and Davis perhaps thought he knew and could control Breckinridge with threats of censure on the the trumped-up charges Bragg had lodged. In this case as in all others, Davis was no judge of men (and perhaps not of women either). Breckinridge took the assignment exactly because he knew the end of days was coming, and he hoped to see an honourable peace as outlined above, and would work hard and intelligently to achieve it.

While the Confederate government remained in Richmond in February 1865 Breckinridge schemed, planned, plotted, and conspired with likeminded others to pressure Davis to face facts and seek peace. It is both heartening and depressing to see that their efforts were constrained by respect for constitutional provisions setting forth presidential powers, upholding states’ right, making supreme the civilian control of the army, and so on. Breckinridge himself was so rule-bound and though he found others who agreed with him about the need to seek peace now, they were also rule-bound. Still others were unwilling to take a position because they still hoped for some benefit from the situation. Even in March 1865 there were some Confederate Senators who aspired to succeed or replace Davis. The ego drove some to hope to be themselves President of the Confederate States of America even as it dissolved. (Pedants note, Confederate presidential elections were scheduled for 1867.)

But Breckinridge never had in mind a coup d’état which would only create more dissension, animosity, and confusion. He and all he involved adhered to the letter of the Confederate Constitution. While the most prestigious figure in the Confederacy General Robert E. Lee agreed with Breckinridge, this demigod would not overstep the chain of command. He reported to Davis and took his orders from Davis and he would not depart one iota from that, though at the same time he would lay out the unvarnished truth of the situation to Davis in his reports. These Davis would hear in silence and as always thereafter speak of redoubled efforts. Breckinridge spent several twenty-four hour days trying to coax and coach Lee into submitting a written report that implied, if did not say, surrender. Lee would never go quite that far. The conclusions to be drawn from his reports were the responsibility of his political masters.

Breckinridge tried at the same time to put together a coalition Senators and Representatives to arouse the Congress to ask the President to report to it and during the subsequent debate the peace initiative could be raised. He could not quite gain the support of the right individuals or in sufficient number.

He also tried winning over this half-a-dozen cabinet colleagues to speak as one to the President to seek peace. Some were so jaded by then as to be indifferent. Others kept alive their own ambitions, if not to succeed Davis, then to return to a political career in a state. One was a complete David sycophant. To win one man over was to alienate that man’s rivals.

He also tried to find a way for the State Government of Virginia to recall its citizens from service in the Confederate States of America armed forces, thus emasculating them in the East, and then for Virginia to secede from the Confederacy on the assumption that other states would have to follow that example and so bring an end to the fighting. The Confederate Constitution recognised state sovereignty.

To sum up, Breckinridge tried six or more different approaches, singly and in combination, to create a coalition for an an honourable peace in the Confederacy. He tried cabinet. He tried the Senate. He tried the House. He tried the state of Virginia and later North Carolina. He tried the leverage of General Lee’s prestige. He tried, later, General Joseph Johnston’s last remaining army as leverage. He tried some of these avenues more than once and several in combination.

He tried to influence Lee to sign his order of surrender on 9 April 1865 as Commander-in-Chief of the Confederate forces, a hollow title Davis had bestowed on him in earlier. Breckinridge thought that nomenclature would justify the end of hostilities across the board. Instead Lee directed his order to surrender to his field command, the Army of Northern Virginia in his General Order Number Nine. He felt he had no larger authority to dictate to others in Mississippi, North Carolina, or Texas.

That might have been enough to keep a normal man busy, but while Breckinridge was doing all of this, and more, he was also managing the largest, most complex, and important department of the Government of the Confederate States of America, accomplishing feats of provisioning, storage, and distribution that had baffled his predecessors. Lee commented on the irony that his army had never been so will stocked with food, uniforms, and munitions as it was in the last few days of its service. That fact he attributed to the labours of Secretary Breckinridge.

To no avail, and on 2 April, General Lee withdrew the scarecrows of his army from the earthworks at Petersburg and fled south and east to avoid the closing jaws of the Union army. The government now had to evacuate Richmond which was open to Federal assault. Breckinridge had no general authority, but as Davis was nearly comatose with shock, he took it upon himself to organise the selection of archive material for destruction or shipment, the opening of warehouses to distribute the food and clothing that remained, before the Federals arrived and took them, the burning of bridges, the assembly of wagon trains to put the government into flight, and to piece together the railway trains to transport the cabinet and the treasure (perhaps $500,000). He also managed to raise a scratch force of horsemen of several thousand to escort the wagon trains.

By default Breckinridge became the de facto manager of the government’s flight and gradual decay. All the while he continued to search for a way to produce an honourable peace.

Nothing was easy and nothing worked smoothly. When they came at all, the trains were five or six hours late. Roads were impassible in the mud of early spring rains and horses were near starvation to begin with. People got lost in the confusion. Mobs choked streets in fear of the coming Federals. Looters got to work. In the confusion arsenals in Richmond were destroyed, setting fire to much of the city. There were fears and rumours of an armed slave uprising fomented by the Federal cavalry.

Apocalyptic it was.

There was no plan except to get the government out of Richmond. Breckinridge hoped it still might bring an honourable peace, though the capacity to do so diminished with Lee’s surrender, while Davis spoke of, take a guess, redoubled efforts. The merry-go-round stopped briefly at Danville Virginia. The cabinet set up shop in front parlour of a private home. Davis wrote a message to the people calling for…redoubled efforts. Breckinridge gathered intelligence about the armies and tried to find a way to make peace through the state of Virginia or then North Carolina.

Federal cavalry was out in force looking for this government on wheels, and Danville was so obvious a place that burned bridges or no, it had to move on, to Greensboro in North Carolina and on and on further south.

There was no master plan and it was only Breckinridge’s initiatives that kept the wagons rolling. The group started with thousands of men, soldiers and civilian officials, and their cargo and camp followers, and other citizens terrified of rumours of the Federal atrocities (attributed to black troops, who truth to tell were themselves victims of atrocities).

The purpose of the flight changed as time went on from (1) negotiation, (2) maintenance of social order, (3) personal safety and exiles of Confederate Government officials, and (4) to assist Confederate soldiers who had surrendered to get home, (5) to settle the outstanding debts of the Confederate government with that dosh. The disintegration of Confederate armies rendered negotiation moot. Social order did break down. As soon as the caravan left a town, the government stores, offices, and warehouses as other public facilities were ransacked, looted, and pillaged. As word spread of the comprehensive defeat, other civilians took to the hills, partly to escape the feared Federal atrocities and also to escape the likes of Quantrell.

There was never any intention to take the government into exile, though some of its individual members might go into exile to avoid Federal retribution, especially for the murder of Lincoln, which many in the North thought was a Confederate deed.

Breckinridge tried, on the retreat, to preserve War Department records. Those left in Richmond were put into fire proof safes, not all of which proved to be fireproof. As they shed wagons, railway cars, and load, more and more paperwork was left behind. Much of this he tried to leave in the safes of local banks, and in other cases put into chests and buried. In part he wanted the historical record to show what had happened. This accuracy of record became even more important with the murder of Lincoln. He wanted to demonstrate that the were was no involvement of the Confederate War Department.

He also held onto some of the paperwork long into the journey to the annoyance of some in the group because it slowed the pace. Among the papers he kept at hand were dossiers, documents, charge sheets, affidavits, testimony that identified Confederate officers who had committed atrocities, usually on black Union soldiers. While en route he tried to locate one such officer who had killed helpless black Federal prisoners. This had occurred in an area where Breckinridge had nominal command on paper, though he had become Secretary of War and had left the department, his name was still on the letterhead. That made it personal since these murders had occurred in his name.

Breckenridge authorised the dispersement of the treasure along the way to pay off soldiers in the escort, to buy provisions, shoes, and clothes for paroled soldiers trying to get home, and to buy medicine to treat wounded men. He himself took the soldier’s pay of $26.60 out of the hundreds and thousands he had in hand. This was the amount all soldiers. regardless or rank were paid, Several of his cabinet colleagues were much more grasping according to the assiduous financial records kept even on this trail of tears.

The trip goes on and on, as the group splits, and takes different routes. At the end of May after some weeks in the swamps of south Florida, Breckenridge made it to Cuba, His last act as an official was to appeal through the resident American journalists in Havana for all Confederates to lay down their arms and accept the result. After some years in exile he returned to Kentucky and lived quietly, refusing an invitation from President U.S. Grant to re-enter politics. His health had been badly damaged by war wounds and then the diseases and hardships of the flight through Florida.

Early in the odyssey he become the first and only Secretary of War to lead troops into battle when he led the cavalry escort in a counter attack on Federal pony soldiers who threatened the column (p 99). Would contemporary Secretaries of Defense be less likely to put boots on the ground in combat if the boots were theirs? Or their children’s? The answer is obvious: Yes.

Our author says Breckinridge, as a former Vice-President (1857-1861), was the most senior political figure to side with the Confederacy (p 167). Former President John Tyler (1841-1845) did so, too, serving as a Congressman from Virginia in the Confederate House of Representatives until his death.

A stylistic quibble, ’Secretary of War’ should surely be in capitals since it is a title, like a proper name but it is not.

I read this book near the publication date and when the upheaval of moving brought it to light again, I put it aside and dipped in, but once in I kept going since it is such a compelling and fast-moving story with a cast of characters from the ever-smiling in the face of adversity Secretary of State Judah Benjamin, the taciturn President Davis, the demigod Lee, the clever temporiser Joseph Johnston, the man of the hour Breckinridge, and many lesser known figures who rose to the occasion.

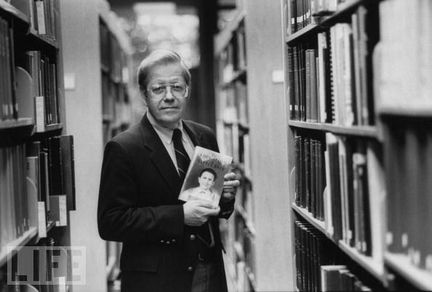

William Davis

William Davis

One such instance of rising to the occasion occurred when a month into the flight, Davis summoned the brigade commanders of the 2,500 escort troops to an audience. When they assembled, Davis spoke of redoubled efforts and still more sacrifices as they stood in dumbstruck silence. Davis expected them to salute in agreement. He did not assemble them for advice or debate but to agree with him and to obey.

As the silence prolonged, he finally asked them to respond. To his credit, the senior man of the five brigadiers, George Dibrell, stepped forward and said it was hopeless situation and useless to ask more of his men who had continued this long out of personal loyalty. In turn, the other four concurred. Davis paled, and as always when confronted with contradiction went into his shell. There was more silence. Finally, Davis’s manners returned and he dismissed them only later to bemoan their lack of resolve. All praise to General Dibrell for calling a halt to the madness.

Category: Presidents

‘George W Norris’ (2013) by Gene Budig and Don Walton.

George W Norris (1861-1944) of McCook Nebraska did much to make the United States what it became. He represented the third district in Congress for ten years, winning five elections, and then went to the United States Senate where he served five terms, thirty years.

Published in 2013.

Published in 2013.

He supported and championed liberal and progressive causes, as did so many of his fellow Republicans in the era of Teddy Roosevelt, but if Republicans changed, Norris did not.

He left his mark in three distinct ways, one in Nebraska and the other two nationally.

1.During World War I the Federal government built a cataract of dams and power stations in northern Alabama at Muscle Shoals to power factories to produce munitions. At the end of the war, the assumption was that it would sold off for a few dollars to commercial interest who would exploit the complex of energy and factories.

But why should private corporations reap the benefit of the immense public investment in the complex, asked George Norris who then introduced a bill to have the Federal government operate the complex as a public utility.

This was socialism, cried the business interests, which grudging lifted the offered purchasing price a few dollars. Norris lobbied hard, bombarded the press with facts and figures during the Coolidge administration, and, because his opponents underestimated him, he secured a majority vote for his bill in the Senate. The first time it passed, it then died in conference committee with the House of Representatives.

George W Norris

George W Norris

Norris was seasoned and he knew that it would be a long road, so he was ready in the Hoover administration with a second bill, re-worded but with the same effect, and it, too, passed, and this time it passed the through the conference committee and went to the president who dealt it a pocket veto.

When Norris presented his third version, Franklin Roosevelt was president, and Muscles Shoals became the first brick in the Tennessee Valley Authority. The hue and cry over the TVA raged for years but it came to be. See ‘The Wild River’ (1960) for the human side of the TVA.

The TVA

The TVA

2. That the electricity produced by the damns sustained the second major theme of Norris’s career, Rural Electrification. Readers of ‘Sad Irons’ by Robert Caro know just how revolutionary electricity was in the lives of untold millions. This, too, was denounced as a Communist plot, along with fluoride in the water.

Few will realise how stoutly the advance of Rural Electrification was resisted. The arguments against it are the old chestnuts much in use today about the evils of big government and the corruption of the flesh by easy living. Having electricity on tap would sap the vital energies of the people, and thereby lay them open to ever greater repression conveyed by radio propaganda….. Yadda, yadda, yadda said the Ann Coulters of the day.

3. The Nebraska element is the unicameral legislature that remains unique among the fifty states. Norris had seen in Lincoln and in Washington how the two houses of a legislature work and arrived at a counter intuitive conclusion. The more representative the houses, the less representative was the legislation. Already this is too hard for an ABC journalist out to demonise someone.

Invariably the two houses would pass bills that differed from each other and these two versions would have to be reconciled in a conference committee, typically of five individuals. This is standard operating procedure, and it is still is. This reconciliation goes on behind closed doors an is usually reported to the two houses in a list of items at the close of session without debate or fanfare.

Norris had seen legislation completely changed by a conference committee of five. The greater the volume of legislation, the more was delegated to conference committees, the less oversight there was applied to them.

He started a one-man campaign for a unicameral legislature and he kicked off in Hastings on Platte to reform the Nebraska state legislature by making it unicameral to squeeze out of existence this process of the conference committee. In a one-house legislature, he reasoned, all business would have to be done in the house, i.e., in public.

He upped the ante by also insisting that this unicameral be non-partisan. His proposals offended both political parties and the Hearst Press, the ‘Omaha World Herald,’ which thundered against this double-edged communist proposal: doing the public business in public! The lies and calumny was dished out Fox News fashion.

Against this mighty array of forces, Norris had two even more powerful allies: The Dust Bowl and the Great Depression.

These catastrophes convinced many that things had to change. Business as usual was inadequate to either of these challenges. In 1934 Nebraska adopted a non-partisan unicameral legislature. The monumental state capital building, only recently completed, had allowed for a second smaller, upper house which then became used for, among other things, the venue for auditioning contestants in a state-song contest. Ever practical those children of the soil are on the Great Plains.

By 1936 Norris was persona non grata in the Republican Party and he ran for re-election as an independent. Norris won then, but in 1942 lost to a real Republican, Kenneth Wherry, who is perhaps best remembered for anticipating Ann Coulter in claiming that all homosexuals were subversives and perhaps the other way around, too. Wherry is accorded all honours in the Republican Hall of Fame and Norris is absent entirely.

‘Oscar Underwood: A Political Biography’ (1980) by Evans Johnson

Oscar Underwood (1862-1929) was contemporary and sometime rival of Woodrow Wilson, William Jennings Bryan, and Eugene Debs.

Born in Alabama during the Civil War, Underwood’s childhood was during Reconstruction when the South was occupied and pillaged to pay reparations for the war. In particular the Republican Party descended on the South to insure it would never cause trouble again by manipulating laws and voters. This baleful episode was ending when Underwood came of age, but its legacy continued (e.g., in those Confederate flags on state capitol domes).

Patrician by birth, he was a man of his time and place. He thought women should be pregnant or in the kitchen or both. Negroes were beasts of burden best kept under strict control. Southern Europeans were failed human beings. Organised labor was anathema. In his political career, to be described shortly, he was parochial, only what was good for Alabama was important.

Why read about such an obscure figure? I am glad you asked that question, Mr. Spock! (1) He was a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in the famous hung convention of 1924 and (2) he was one of the ‘Profiles in Courage’ (1957) television series for his confrontation with the Ku Klux Klan. The little I knew of these events made them seem odd for an Alabaman of his time and place. (3) Having just read about the egregious Alabaman George Wallace, I wondered about his fellow Alabaman. Now is the time to find out more.

Underwood ran for Congress and represented the Ninth District (Birmingham) just as the Republican ascendancy was ending. He joined with many others to purge electoral rolls of blacks and to keep them off thereafter. He developed a lock on the Democratic Party nomination as the Republican Party died in the South.

He toadied up to the Speaker of House of Representative Champ Clark who had presidential ambitions. Clark rewarded him with the chair of the House Ways and Means Committee. At the time this was a minor post, but Underwood made it into an important one with some creative thinking, hard work, and unfailingly politeness. Underwood became indispensable to the business of the House. He was ever present, always ready to do what needed to be done, even if strictly speaking someone else was supposed to do it, no job too big, no job too small. He also proved to be adroit in stroking the many egos that needed to be stroked.

His main interest in Washington was tariffs affecting his constituency, and he laboured over the tariff schedules as though they were holy writ. He had always loved facts and figures and this subject played to that strength of this born accountant. The tariff was a major national issue and he became the master of the detail of tariff schedules, the impact of item #116 on Schedule B in Part 1.21 paragraph 2.0 on his constituency, and he soon schooled others in this detail, too, as it applied to their own constituencies.

The Ways and Means Committee, then as now, manages the business of the House of Representatives, and Underwood used this as an instrument to impose party discipline. In fact, in hindsight it seems that he had more success in securing party discipline than at any other time in the history of the House. Only when there was a two-thirds majority vote from Democrats in the Party Room, would he bring a matter to the floor of the House for a vote, but then he expected 100% compliance from Democrats on the floor of the House. Dissenters soon found strange delays in office cleaning, faulty telephone lines, etc. Nothing terribly subtle about it but then there was nothing personal in it either.

In time he grew bored. Holding the Birmingham seat was foreordained; he had party discipline to a fine art. He now contracted that virus so common in Washington, Potomac Fever. He became to think of himself as a statesman, and became a little less parochial, and he began to think another Southerner might one day soon be elected president. That Southern might as well be Oscar Underwood as anyone else. He was right, it was time for a Southerner: Woodrow Wilson.

In the 1912 Democratic Convention Underwood was one of the nominees, positioned to be a compromise candidate if the front runners, Clark and Wilson failed. Wilson prevailed, and he sounded Underwood out for the Vice-Presidential nomination, but Underwood declined. I am not at all sure how serious that sounding was, because even the naif Wilson must have realised two sons of the South on the Democratic ticket would be one too many.

Wilson’s victory was a Democrat landslide and the House majority became gigantic. Underwood used all the tactics, techniques, and tricks he had learned to discipline the mob of newbies that entered the House, each determined to right all wrongs, and change everything for the better. By that time he was an old hand at managing such upstarts. They soon discovered just how unimportant a Congressman is when there is a 100-vote majority. The object lessons were quick and decisive. Outspokenly independent Democrats had no office space, no secretarial assistance, the postage franking certificate was lost…. His handshake was firm, his smile warm, his determination to lead was Birmingham steel.

While Underwood personally had no time for the amateur newcomer Wilson, he sailed with the wind in Wilson’s canvas. And besides Wilson was far preferable to Bryan, in part because Underwood must have supposed he could manipulate Wilson, though the author is silent on that possibility. Wilson’s preoccupations with the high road and his absolute belief in the separation of powers meant that he left Underwood to run the House, and run it he did.

The first item of business was the tariff, and in the new Congress no hotel vouchers were issued, no office-space was assigned and no committee posts allocated, until the tariff schedules Underwood had devised over the preceding years had been passed. He really did hold them to ransom. Pass my tariff bill (it was an omnibus bill with 57 parts to make it harder to be amended, split, or qualified with riders) or else a new Congressman may never have had an office to sit in let alone a committee seat to brag about back home. Likewise he managed the floor debate with an iron hand. Debate was permitted but not one word off the topic was tolerated, nor were any extensions of time to debate granted. A speaker who wandered off topic would be handed a note from Underwood asking him to yield.

While the small Republican minority squawked, many of them enjoyed the spectacle of new Democratic Congressmen learning the Washington game the hard way. If Underwood’s touch seems heavy, it was light compared to that applied by the previous Republican rule when debate was often not allowed.

Underwood was both a social conservative and also a fiscal conservative, yet he steered Wilson’s progressive legislation through the House of Representatives. Politics makes strange bedfellows they say.

Like many other Southerners, to Underwood the Federal government was the enemy, and he constantly voted against appropriations for any and everything, unless the money was to be spent in Birmingham. He was one of the majority who voted to cut defence spending, public health spending, education spending, funding for scientific research, staffing for foreign missions, and so on and on. The only Federal dollars he voted to spend were those bound for northern Alabama. When, however, Potomac Fever gripped him he did try to broaden his outlook, though his heart was not in it.

With Wilson in the White House, and the House proving ever harder to control, Underwood decided to move up. He secured the Democratic nomination for an Alabama Senate seat. He fought off a challenger in the Democratic primary and easily won the election. The challenge was based on what was the central issue of national politics for some years — prohibition.

After twenty years in the House of Representatives with many accolades, Underwood entered the Senate as the newest of the new boys, and found an altogether different atmosphere. The Senate was a club whose members indulged each other. There was no urgency. Underwood who had insisted on party unity and discipline in the House became himself a dissident voice in the Senate, often speaking against Democratic measures, though at the end of the day he usually voted for them, a ploy that remains common today. Speak one-way and vote the other in the effort to please both camps. Thereafter he would often then vote against the appropriation of funds for measures he had earlier voted for. Another ploy that is time-honoured.

However Underwood did not enjoy the pleasures of the iconoclast for long and soon began managing bills in the Senate and by the beginning of his second term, he was Democrat leader in the Senate. The foreign crises with Mexico and Germany did not interest him much but he went through the motions that his ambitions required. He supported Wilson in the Great War (making sure plenty of contracts went to Birmingham) and then the Treaty of Versailles but without conspicuous energy or wit.

He had been nominated for the Presidential place in the 1912 Democratic Party convention which Wilson won. Had Wilson stepped aside in 1916, and there were such rumours, he would certainly have tried for it. In 1920, well the time was not right. He was up for re-election to the Senate and Alabama state law prohibited anyone from being a candidate for two offices in the same election. He preferred to secure six more years in Washington by contesting the Senate primary and election with an eye on 1924. He campaigned for the Democratic Cox-Roosevelt (F. D.) ticket nationally though it was a lost cause from the start.

At last we come to the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan was rooted in the South and had been rejuvenated by, of all things, the prohibition movement. It was violently prohibitionist, as it was violently racist, violently anti-Catholic, xenophobic, anti-union, misogynist, anti-intellectual…..

Underwood position on prohibition was local-option. Let each community decide for itself. That satisfied neither the Wets nor the Drys. Though Underwood was flexible and pragmatic on most issues that did not effect the material well-being of his constituents, he did stick on a few, and prohibition was one of those.

Strange right there. Alabama was prohibition heartland, leaving aside home-brew, and the Klan had been founded there. (I thought about including some Klan pictures, and there are plenty to be had, but they were all so vile, I did not.)

Perhaps it was his patrician outlook or the insulation of so many years in Washington D.C. that made him insensitive to this populist cause, but he would brook no compromise on this issue, though his entire legislative career was based on knowing the time to compromise. Moreover, when he launched his bid for the Democratic nomination he went to Texas, where the official headquarters of the Klan was located, to do it, and denounced the Klan in a speech in Houston: ‘It was a secret society that took the law into its own hands.’ The battle began. There were two other leading candidates, William McAdoo and Al Smith. McAdoo was ultra-Dry and Smith, as he used to say, was all-Wet. The Klan supported McAdoo and reviled the Catholic Smith as Satan with smile.

Again Underwood’s strategy was to be the compromise candidate if McAdoo and Smith stymied each other. He did not make the Klan the sole issue but he did repeat it many times in speeches in the north-east, mid-west, and the south. The 1924 nominating convention was in New York City and the Klan timed its national conclave to coincide with it across the river in New Jersey to show its force. Underwood introduced an explicitly anti-Klan plank into the Democratic platform, which was defeated. The gloves were off. The convention was marked by fistfights in the hall, clashes of marchers for and against the Klan in the streets, arrests of delegates, a spectacle that H. L Mencken adored. Underwood’s confrontation with the Klan, won him support from the north and west but eroded his southern homeland. This convention lasted three weeks and went to 102 ballots! As the wits said, ‘We have to make a decision, or move to a cheaper hotel!’ The nominee was John Davis….

That was high-tide for Underwood who returned to the Senate, and quickly lost interest in most things. His health had never been good, and now aged sixty-seven it got worse. He retired and spent the time dictating memoirs.

Apart from the strategic reasons of gaining a national profile in his confrontation with the Klan, I cannot understand from these pages why he did it. If it was a national profile he wanted, there were plenty of other issues to pursue that would have been less risky to his southern base, e.g., the tariff, railways, immigration, taxation, and so on.

In a fine concluding chapter the author sums up Underwood as a man of moderate ability who mastered the arcane rules of the House of Representatives and then the Senate in succession and led both, the first man to do that since Henry Clay, and the last one to do it. The author gives Underwood no moral credit for his conflict with the Klan, interpreting it purely as an electoral strategy, but that just seems too simple to this reader. If anything, it effectively made it impossible for him to be the compromise candidate between McAdoo and Smith, since it assured vehement opposition from the Drys, with and without hoods. If that was the aim, it was misguided from the start, this from a man who always counted the votes twice before they were cast. To get the necessary two-thirds of votes to win, Underwood would had to have some of McAdoo’s votes, and they should have been available to him as McAdoo was also a Southerner from neighbouring Georgia. The author does do a calculation that shows if Underwood had kept his Southern base of Alabama, Mississippi, Florida, Arkansas, and South Carolina he would have had a chance.

The book is an account of his political career, much of it paraphrased from the Congressional Record. [Cue, sound of dust settling.] In some passages we get a day-by-day account of the Underwood’s committee hearings, floor speeches, and roll call votes. It was a PhD dissertation and it shows in the mind-numbing and pointless detail. None of this reveals the inner man.

I could not find a picture of the author.

I learned virtually nothing about Underwood’s childhood and how that might have shaped him for later life, like the legacy of the Civil War on this child or his boyhood experiences with blacks.

Oscar Underwood was not related to the New Jersey Underwoods who made typewriters. Nor is he related to Frank Underwood. [Get it?]

Hitler or Churchill, who was the democrat?

Who was the democrat Winston Churchill (1874-1965) or Adolf Hitler (1889-1945)? (For those readers who do not recognise these names, stop here and turn on 7MATE, the two of you deserve each other.)

Wait! Before answering think! What does ‘democracy’ mean?

Most of the time, most people think ‘democracy’ means voting, voting, voting, and counting the votes. Journalists intone the solemnity of leaders submitting themselves to vox populi. Well, the voice of the people, since most would not dare use Latin, even if they knew it.

If voting is the criterion, how do Churchill and Hitler compare?

Short answer: Hitler led his party in far more elections than Churchill did.

Hitler was a candidate for chancellor in five national elections between 1928 and 1933. In those parliamentary elections the vote for his Nazi Party grew from 3% to 44%. He heard the voice of the people. In addition, he led his party in elections in several German states in that period. Moreover, he held a plebiscite in Austria to confirm the Anschluss (the unification of German and Austria).

Hitler campaigning in 1932.

Hitler campaigning in 1932.

Churchill, the great war leader and champion of democracy, became Prime Minister in May 1940. There was no vote. The Conservative Party changed leaders. There was no election in Great Britain during World War II (though there were in Australia, Canada, and the United States). The last general election in the United Kingdom had been in 1935. Churchill’s government decided not to call the elections due in 1940. Imagine the fuss a shock-jock would make of an incumbent government not facing the scheduled election. Horror! Outrage! Cliché!

Only in 1945, after the European War was over did Churchill call an election, and he lost, and lost decisively. (He remained leader and led his party to victory in 1949, that being the only election he won as leader.)

The 65-year old Churchill on his first day as Prime Minister in 1940.

The 65-year old Churchill on his first day as Prime Minister in 1940.

Yet, I would say Churchill’s claim to the title of democrat is greater than Hitler’s. Why?

First, Hitler campaigned in election-after-election AGAINST democracy. He proclaimed the idiocy of choosing leaders by votes and promised to do away with elections, once he had the authority to do so. He was explicit and overt about this. Elections counted the votes of Jews, bankers, women, trade unionists, Gypsies, homosexuals, cripples, and others equal to Aryan votes. ‘Stop that at once!’ he declared. He used the campaigns to air his views, identify, educate, mobilise, and license supporters. As the strength of his party grew in 1932 he unleashed those supporters to intimidate voters, forge ballots, burn ballot boxes from Jewish quarters, threaten voters at polling booths…

These are the facts.

We might speculate that had Hitler called an election in August 1940, November 1941, March 1942, even in February of 1944, he would have won easily and by a big margin. Here is a guess, he (and the Nazi Party) might have garnered 80% of the vote or more. There was after all no opposition left but we could imagine that one of the conservative agrarian parties that merged with the Nazis in 1930 breaking away as the opposition, against them Hitler’s victory might have been 90+%. The contrast is Churchill who called an election in July 1945 and lost while the Asian War continued.

Hitler greets the people after being sworn in as Chancellor.

Hitler greets the people after being sworn in as Chancellor.

Second, Churchill’s claim rests principally on his unstinting respect for and use of parliament during the war years. First he formed a national war cabinet by including the Labour opposition, and second he submitted himself and his government to parliament which remained supreme, though the mandate of its members had lapsed. He explained and justified his actions in parliament, and he replied to questions and criticisms. He permitted the criticisms in the first place. Churchill kept and respected the institutions of British government, including the courts, whereas Hitler fused authorities and abolished institutions, reducing everything to personal loyalty to him in the army oath, and executive orders. It is this respect for and adherence to procedure, process, and practice that adds credit to Churchill’s democratic account. Of course, it is true that there were compromises in the name of the war effort and security, and some of the constraints were probably unnecessary when judged in the cold, clear light of hindsight, but the fundamental institutions remained; there to be re-awakened.

In so doing, Churchill left the democratic culture of Britain undiminished. Men and women grumbled about the government, questioned the need for rationing, complained about health care, suspected profiteering, and wrote letters expressing their vexations to members of parliament, to the BBC, and to newspapers. Newspapers picked away at the foibles and mistakes of government ministries. During the height of the Battle of Britain, during all-clears orators on the ladders in Hyde Park, London, excoriated the British government for its continued hold on India. This was all constrained but compared to Germany after 1933 it was a riot of freedom.

By the way, there was a great deal of opposition to Churchill, within his own party for a start. He was too belligerent many thought, including the first of his foreign ministers. Some Conservatives wanted him to fail and be replaced by a more pliable figure. Theirs was a whispering campaign, true, but it would have been exterminated in Germany, whereas Churchill combated it though parliament.

Conclusion? Voting alone does not democracy make. A small conclusion it might seem but it has major implications.

‘The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, The Origins of the New Conservatism, and the Transformation of American Politics’ (2000). 2nd ed. By Dan T. Carter

Three men publicly declared their intentions to run the first time for public office within hours of each other, one in Massachusetts, another in California, and the last in Alabama: John Kennedy, Richard Nixon, and George Wallace (1919-1998), and despite his four presidential campaigns the latter, Wallace, has all but disappeared from the popular consciousness. The evidence is celebrations of anniversaries reported to television and the shelves of bookstores. Kennedy and Nixon appear now and again in those places. Pigmies (journalists) till occasionally try to hack a byline out of Kennedy or Nixon. Scholars continue to evaluate their achievements in monographs. The fiftieth anniversary of this or that has commanded television time. Hits on the internet are millions for Kennedy and Nixon.

But George Wallace, though in the time he preoccupied both Kennedy and Nixon, and commanded headlines around the world, is now all but forgotten except to specialists in American regional politics. Moreover, later in life, outwardly Wallace executed a 180 degree turn in his public persona and went from a fire-eater to a grand old man. Who was George C. Wallace?

He was the oldest son in a comfortable family, though its fortunes had declined in the previous generation, along with millions of others when the Great Depression hit. George completed high school and graduated from the University of Alabama with the help of the G.I. Bill of the (later despised) federal government.

He was small, and often called ‘Little George’ rather than ‘George, Junior. ‘ If that irritated him, he found an outlet for any resentment in Golden Gloves boxing. He did well in that as a bantam weight. More than once knocking out an opponent. As one coach said, George did not want to win the fight, he wanted to hurt his opponent. Trying to teach him to score points for a technical victory had no effect. George did not want to score points, he wanted to deck his opponent, draw blood, and have KO recorded. The pugnacity he showed later was there from the beginning.

He had served in the United State Air Force in the Pacific War and flew nine missions in a B-29 over Japan. He was the flight engineer for the large and complicated airplane. While the Japanese defences were weak sometimes it only took one hit to bring down even one of these super fortresses. In addition, the distances, the weather, the fatigue of the crew on 16-hour flights in combat conditions, and the temperamental nature of the aircraft combined to produce 5% losses on every sortie; if 500 planes took off for a mission, 475 made it back. Each plane carried 11-crewmen and so that meant 275 deaths. Yes, deaths because when the planes went down, whether over Japan or open water, all hands were lost. Air-sea rescue existed but the vast expanse of the Pacific ocean over a 6,000 mile course made recovery a million-to-one shot.

On at least one flight Wallace’s handling of the engines, the fuel flow, the oil pressure, the hydraulics saved the plane from disaster. Later he secured an honourable discharge despite some dubious behaviour. (From the details in these pages I rather think he served in the same unit as my father, likewise from the South, but there the similarity ends.)

When the war started Wallace knew he had to serve in order to secure his future political ambitions. And he had political ambitions that were articulated from about 15 years of age. He earned a place as an intern in the Alabama legislature and declared that one day he would be governor. Many a boy and today many a girl has done something like this. Few of them, however, conducted the kind of campaign he did to secure that internship. In early summer when school was out his father drove him to the capital, Montgomery, and young George laid siege to the legislature like Grant before Richmond. He had already written a stream of letters to every member of the legislature explaining his exceptional merits for one of the very few internships available, pledging to serve above and beyond the call of duty. Once in Montgomery he presented himself at the door of one legislator after another and talked his way into most. He slept at least one night in park and gave his suit an undergraduate iron, i.e., he slept on it. His father left him to his own devices. For the first but not the last time, Wallace wore down his adversaries and he got an internship. He loved it, and did do twice the work any of the others.

The man was something of a loner despite coming from a family of five children. He could keep to himself for days at a time, as he often did during this internship and later in the Air Force, but if he was with other people he was garrulous, excited, nervous, twitching with energy, and talking, and talking, and talking nothing but politics as one contemporary after another says, though what politics he talked from fifteen onward is not clear.

What is clear is that he had a burning ambition and politics was the field. The two defining poles of Southern politics were (1) hatred of the North (Federal) government because of the Civil War and Reconstruction and (2) white superiority at the cost of black oppression. The former meant that the federal government was the real enemy, though the largess from FDR’s many programs was quickly pocketed in the South, it was nothing more than overdue compensation for the great evils the North had visited on the South. Suitably encoded for contemporary sensibilities, we hear the same motifs today from the Tea Party and its media service, Fox News.

Leaving aside the details, which are thoroughly documented and dramatically presented in this book, from the beginning Wallace was a hollow man.

Wallace had a gigantic need for recognition which translated into an unquenchable ambition for political office (even before taking the oath of office as governor the first time he referred to running for president ‘next year’) that combined with his belligerent temperament. To serve that ambition he would cheat, steal, and lie while denying everything. His defiance of the federal government on civil rights was – it is abundantly clear – contrived to lock-in the white vote for his ambitions. He had no interest in the constitutional or legal aspects of the dispute. Nor did he seem to have any personal animosity to blacks. As Hitler never personally harmed a Jew, so Wallace never harmed a black person. Racism was necessary to win and he would not be out done in that. No sir! If racism got votes, he would talk racism day-and-night. Against such singleminded determination, the federal government wobbled. The Kennedy Administration wanted compromise not confrontation but Wallace wanted confrontation (before the television cameras) and not compromise of even the most cosmetic kind.

Wallace promoted the mayhem of Selma and the maelstrom of Birmingham. The descriptions of the bomb, the razor, poison, the truncheon, C-4 teargas (which is toxic), the torch, the shotgun, the knife, the pistol, the high-pressure firehose that broke limbs, the baseball bat, and the snarling police dogs, and let us not forget the electric cattle prods were, as one French journalist said, worse than any he had ever seen in banana republics. Wallace was indifferent to the blood he had let, ever ready to blame someone else. His message was clearly understood by those whites who wanted to fight. The haters came out in force and Wallace privately invited the Ku Klux Klan to mobilise to the drive the blacks off the streets.

George Wallace. ‘Segregation now! Segregation tomorrow! Segregation forever!’

George Wallace. ‘Segregation now! Segregation tomorrow! Segregation forever!’

Before reaching for stereotypes about Alabama, it might be noted that in the 1920s a governor of this very same state, Oscar Underwood (1862-1929), sacrificed his political career, including his own presidential ambitions, to confront the Klan. Equally, Wallace’s immediate predecessor in the gubernatorial chair, Jim Folsom was an advocate, albeit inconsistently, of racial accommodation. Wallace’s constituency was always a minority but it was an intense minority that he had identified, legitimated, recruited, mobilised, and unleashed with the full support of the state government and the connivance of some of Alabama’s Washington representatives and senators. I said ‘recruited’ because there is evidence that some of the perpetrators had flocked to Alabama from other states to seize the opportunity to crack skulls.

Wallace had found, as did another Southern midget, Alexander Stephens (1812-1883), that crowds were bored when he talked about states’ rights but responsive when he went in for race-baiting. What was am ambitious man to do, but play the race card? It was the only card in the deck.

Having just read some of the Robert Penn Warren’s essays written at the same time as Wallace was at his pinnacle it is hard to believe these two Southerners came from the same planet.

While Wallace ranted and raved at the evils of the federal government, he continued to receive and bank his monthly check for his war wound. War wound? His discharge was based on his unfitness for further duty due to mental instability, i.e. combat fatigue. For that disability he received a part-pension for the rest of his life. Imagine what an opponent as unscrupulous as Wallace himself would have made of that fact.

Wallace had a retentive memory and he made a point of remembering people he met, because they might be useful later, but he had no rapport with them, unlike Huey Long. They were assets to be catalogued not people whom he could help. Long’s faults are encyclopaedic but he never played the race card. There is a coldness at Wallace’s core, which is also evident in this relationship with women, including his ever loyal wife, Lurleen. So seldom did he see his children that she wondered if he would recognise them in a crowd.

In all he served three discontinuous four-year terms as governor, and his wife, Lurleen, served one four-year term as his surrogate. As to Wallace’s change of heart after his own ordeal, the author is sceptical. Wallace’s injuries were terrible and left him in constant pain. But after so many years and so many lies, perhaps the one person who believed his lies was George Wallace. The author gives very short shrift to this period in Wallace’s life which I took to be a silent comment on Wallace’s credibility.

Reading this book brought back those times to me, and it was disturbing to recall those days of the news each night of blowing up children in churches, burning to death families at the kitchen dinner table, the murder of university students in the street, a woman beaten to death with baseball bats by five men in a town square.… Worse, the culprits in many cases were well known, and some openly bragged of their deeds, others were on-duty police officers. Looking back, it beggars belief. I had no wish to see ‘Selma.’ The original was enough for me.

The author goes to remarkable lengths to be even-handed and let the facts speak for themselves. They do.

Dan Carter

Dan Carter

Presidential campaigns. Wallace’s strategy was to produce an indecisive election, i.e. no candidate with majority of electoral votes, and throw the (s)election of the president into the House of Representatives as prescribed by the Constitution at the time. There a combination of Southerners with some Northerners from blue-collar constituencies might give him enough votes to wangle a Vice-Presidential selection, and from that base the next time he would be the leading contender for the top job. It is not as crazy as it sounds.

1964. Wallace entered and campaigned hard in three Democratic primaries, Wisconsin, Indiana, and Maryland, and did well. That ended the supposition he was a regional politician with no appeal outside the deep South. After dropping out, privately he offered his support to Barry Goldwater in return for the Vice-Presidential place on the Republican ticket. Goldwater declined. LBJ swept all before him.

1968. Wallace ran as a third party candidate with Curtis ‘Bomber’ LeMay. Richard Nixon won but he feared that Wallace would split his vote. Once again Wallace let it be known he would accept the Vice-Presidential slot on first the Democratic and the Republican ticket. This messages were ignored. He got ten million votes, carried five deep South states with forty-five Electoral votes. This was his high tide. He seems to have taken votes from blue collar workers in the North who might have otherwise voted for Hubert Humphrey and from Southern rednecks who might otherwise have voted for Nixon.

1972. Wallace entered the crowded Democratic primary field and won Maryland, Michigan, as well as Florida. Once again he approached Hubert Humphrey through an intermediary about the Vice-Presidential slot and once again Humphrey did not respond. While Wallace got votes, George McGovern’s campaign was more astute at getting delegates, and there was never a chance Wallace could win, but he could certainly be a spoiler. Nixon was delighted to see him in the Democrat chicken coop but worried he might bolt once again and run as a third party candidate. Many calculation were made. Among McGovern’s campaign staff were Bill and Hilary Clinton. Then that weirdo shot him. HIs assailant sought fame and barely knew who Wallace was. One weirdo too many.

1976. In a wheel chair he entered another crowded Democratic primary field but had little impact and dropped out quickly. He was allowed to address the convention, but he was a shadow of the rabble rouser he once was, and his effort to play the elder statesman was lame. Jimmie ‘Who’ Carter won and won again, the nomination and the election.

Footnotes to Wallace

Hatred and fear, these win elections. This was the lesson the Republican Party took away from the Wallace experience it has gradually make its own since. To paraphrase a Republican campaign analyst in 1968, find out what they fear, find out what they hate, and play to those and only to those. If white blue-collar workers fear that lower-paid blacks will take their jobs, play that card. If white middle-class suburbanites fear blacks will move into the neighbourhood and lower real estate values and mix races, play that card. ‘Playing the card’ means articulating these fears for them in a way that is socially acceptable but unmistakeable — code it — so that they can say it and in so doing realise they are not alone. This crystallised into ‘The Silent Majority’ which was hardly silent and probably not a majority, but it was a brilliant conceptualization. People motivated by hatred and fear will go to the polls and vote. Wallace’s campaigns both in Alabama and in northern primaries brought many hundreds of thousands first-time voters to the polls in general or primary elections. That campaign manager used other examples and expressed them much more forcefully than I have done in deference to the PG-17 rating of this blog.

Demeaning accounts in press. The resentment that Wallace bore toward the North and its surrogate, the federal government, is easy enough to understand when reading the contemporary press accounts of him, his followers, and his campaigns quoted here. The ‘New York Times,’ ‘Time Magazine,’ CBC-TV News, all struggled to find a slot into which to place them, and they settled on the easiest one to hand. Drawing on their knowledge of the South from reading Al Capp’s ‘Lil Abner’, the pigmies of the Fourth Estate labelled them hillbillies, rednecks, hicks, yokels, and rubes. The early descriptions of Wallace on the campaign trail in North reek of condescension and deprecation. Everything about him was described as though he were a specimen in a jar, his wristwatch, his haircut, his finger nails, these were all subjected to the journalistic acid test, namely, can I get a byline out of this?

‘Jeremy Thorpe’ (2014) by Michael Bloch

This is a lengthy and detailed biography of one Jeremy Thorpe (1929-2014). Jeremy who? He served in the British parliament for twenty years (1959-1979) and was leader of the Liberal Party, 1967-1976, until a spectacular fall from grace. Educated at Eton and Oxford, he was a scion of the upper middle class of his time and place, reared by nannies, sheltered and seldom disciplined. His mother doted on him as the only boy in the family to the occasional resentment of his two older sisters. Jeremy was fifteen when his father died, and thereafter the money slowly ran out.

When German bombing threatened in 1939 his parents sent him (and the girls) to the United States, where he spent three years in middle school. There he found the environment freer with more emphasis on individuality than the conformism stressed at home. He was neither athletic nor bookish. He had a ear for music and accents, playing the violin quite well (sometimes in public) and mimicking teachers to the amusement of his peers. That combined with a theatrical bent, though he did not act in school plays. He craved to be the centre of attention, dressing to catch the eye, making grand entrances, and saying things to surprise or shock. This is all rather like most adolescent boys, but he did not grow out these but cultivated them as he matured. By the same token he was considerate of others, egalitarian in manner, one who looked to the future and not the past, gregarious, optimistic, and energetic, this latter being, I have always thought, an essential for anyone in politics. His American experience left him with a lifelong commitment to the Special Relationship across the Atlantic.

He had powers of concentration and a retentive memory. He would have made a good barrister, one who could absorb a brief inside out, as they say in chambers, if only he concentrated on it. If someone told him about a book he took it in, and made it his own, so that later if he told someone else about the book, it sounded as if he had read it himself. He focussed on people and he was good at remembering names. When he talked to someone – a duchess at a soiree or a dustman at a political rally — he locked onto them as if, for those moments, they were the most important people in the world. He did not fidget and look over their shoulder for someone else more important to whom to talk. These are assets in campaigning. But he was not particularly adept at debating and if challenged on a point by either the duchess or the dustman he was likely to escape with a quip or laugh.

Much influenced by family friend Lloyd George’s example, he committed himself to the Liberal Party nearly in cradle and never wavered from that though by the time he entered politics, it had been nearly extinguished. His mother was a dyed in the wool Conservative who held an elected office the local shire council, but she was unstinting in her support for his ambitious, and perhaps always hoped that he, like others who started out as Liberals, Winston Churchill and Harold Wilson, would change. He spent his years at Oxford pursuing impressive offices, ending as president of the Oxford Union. He was a very poor student and barely completed the law degree and only passed the bar examination on a second or third sitting thanks to the great effort of a chum to prepare him. He was an indifferent barrister, best at appealing to a jury’s emotions and completely unaware of points of law or court procedure, with no grasp of detail, as more than one judge said. His real interest was always politics.

While a student he campaigned often for Liberals in General and By Elections. When he was old enough, rather than vying for one of the very few safe Liberal seats, which might have been possible due to retirements, he picked a rock-ribbed Conservative constituency that had not voted Liberal in two generations, and set to work and seven years later he was elected. The man had application.

He made little money from law, but when ITV was born he applied for a job there and become the host for a popular science program. In an age when all television was live to air, he was just the man, an easy manner, a ready smile, a quick wit, an adroit ability to segue over cracks in the proceedings. He became a reporter on international news and went to Africa for the independence celebrations in Ghana, and he kept travelling and reporting as the Empire converted itself to the Commonwealth. He met and befriended many of the leaders of the emerging nations in Africa, and did his best to explain their causes to his audience in Great Britain. He had a career in television for some years while still practicing law, when there was client, and working in the constituency. Television gave him exposure but very little money. He practiced law in the constituency, too, at cut rates to establish himself. For years he wore his father’s clothes to save money but that also made him seem a dandy from another age that appealed to his sense of theatre, and he lived at home with his mother in Surrey from which he travelled on British Rail to London and North Devon, the constituency, and in all those hours on trains, he chatted up one and all, some of whom recognised him from television and he lapped that up. The man loved an audience. The first time he ran in North Devon he doubled the previous Liberal vote and lost. Four years later he doubled it again and won.

When Jo Grimond retired as Liberal parliamentary leader, Thorpe became leader of the ten Liberals in the House of Commons. Though the Liberals were then a tiny party in electoral terms they retained an elaborate party organization from the days when they were a governing party, councils, assemblies, committees, and boards in profusion. Thorpe proposed changes to streamline that but those who sat on those councils, assemblies, committees, and boards resisted, though they did next to nothing to promote the Liberal cause in the electorate. He then did the next best thing and ignored them. He had three jobs: member of parliament, barrister in London, and travelling correspondent for television, and now leader of a parliamentary party. It was too much even for him, and he quit the law which brought in less money than the cost of the chambers.

In politics he was a vigorous champion of human rights, at the forefront of many campaigns against apartheid in South Africa and the rebel regime in Rhodesia. He also espoused equality for women and recognition of homosexuality in British legislation. He likewise advocated British entry into the European Community. The high water mark of his career was 1974 when the Liberal won 20% of the vote and in the consequent hung parliament, the prospect of a coalition government arose. The Labour leader Harold Wilson wanted another election, not a coalition. Edward Heath, the incumbent Conservative Prime Minister conferred with Thorpe, but Heath refused to consider electoral reform, i.e., proportional representation, ending that brief episode. Sound familiar? In 2010, for those who have not been paying attention, the Liberals entered a coalition with the Tories and for their trouble were obliterated in the 2015 British election to the benefit of the Conservatives.

Bust of Thorpe in the House of Commons.

Bust of Thorpe in the House of Commons.

In this period Harold Wilson, first as leader of the Opposition and then as Prime Minister, encouraged the Liberals because they siphoned most of their votes from the Conservatives. Accordingly he always treated Thorpe well, invited him to events, praised his speeches, allowed him some patronage to distribute, enacted legislation that gave tax benefits to those who contributed to the Liberal Party, sent cars to pick him up…. By contrast Edward Heath found Thorpe a poseur of no substance, and could hardly abide him and made no such efforts to court him or the Liberal Party. What a triumvirate! Heath the detail-minded plodder, Wilson the wheeler-dealer, and Thorpe the razzmatazz showman.

Ted Heath, Jeremy Thorpe, and Harold Wilson.

Ted Heath, Jeremy Thorpe, and Harold Wilson.

The few people who remember Jeremy Thorpe today most likely recall the debacle that ended his career in 1976 when his name was regularly in 30-point type on newspaper screamers at every tube station in London and throughout Great Britain. He was a homosexual at a time when homosexuals in important positions were, in addition to the social, religious opprobrium, and illegality, were regarded as security threats thanks to Guy Burgess. Added to the animal satisfaction, in Thorpe’s case there was the added appeal of the secrecy, melodrama, and theatricality of secret homosexual liaisons. Such was his discretion that even well-known homosexuals who knew him did not realise he shared their orientation, though in time he became less and less discreet. The author gives quite a compelling account of how homosexuality meshed with Thorpe’s personality without descending into the prurient details of an ABC interviewer. Though a good number of people came to know of his homosexuality over the years, including the police and security services, they turned a blind eye but I am not sure why because as Liberal leader he had access to security and defence briefings. There many boyfriends and they came and went. But one of them, Norman Scott, plagued him for years and years and years. Asking for money, bragging to others of his hold on Thorpe, writing letters to Thorpe’s mother, appearing at Thorpe’s parliamentary office. Scott was by all accounts mentally disturbed though he was good looking and could be personable in short bursts. Thorpe tried for years to find a niche for him, securing a number of jobs for him while giving him money. Scott soon wore out his welcome at the jobs and came ever back to Thorpe for more, and more, and more. He even denounced Thorpe to the police who duly noted the allegation and ignored it, noting that Scott had spent time in more than one asylum.

In 1976 Scott’s life was threatened by a man with a gun who killed Scott’s dog. Did Jeremy Thorpe have anything to do with this…well, there is the mystery? He resigned as leader, very reluctantly, under great pressure from his parliamentary colleagues. Three years later there was a trial for conspiracy to commit murder and Thorpe was one of four arraigned, and it all came spilling out in every last detail. It was a feast for the carrion of the media and every morsel was chewed, belched up, and chewed again. His legion of friends and admirers melted away. The men involved, apart from Thorpe, were dubious characters and with chequered histories. Several were accomplished and repeated liars, and should they now be believed? In the end they were acquitted and Thorpe tried to turn that into a victory, but in the course of the trial a great deal had come out of the tube that would not go back. He ran again for parliament and lost….

In the midst of this sage with Scott, Thorpe married a women who knew his homosexuality but like many others found him engaging, and she enjoyed the glamor or Westminster, lunches at the Palace, trips to exotic Africa, and so on. Moreover, they shared intellectual interests in art and architecture. Many observers have since said that he changed as a result, became less theatrical, more relaxed, more confident. Thorpe timed his surprised wedding to upstage a coup against his leadership in the party, and it worked a treat. She was killed in a car accident two years after marriage and he went into a stunned silence for a year and a half. Emerging only occasionally to perform his public duties. He did re-marry on similar terms and this women stuck with him through the ordeal of the trial.

The book is lively and replete with incidents and colourful characters but at 600 pages the detail is so great, the names carpet bombed that I was lost most of the time. The pages are dotted with endnotes to sources of the assertions made and events reported, and replete with asterisked explanatory notes on the characters at the bottom of every other page or so. The author worked on this study over a 25-year period, interviewing everyone and anyone who knew, saw, worked with or against Thorpe, including Thorpe himself. It is all very dense. The length might also seem disproportionate to Thorpe’s achievements. As far I could tell, despite his many pronouncements no cause, no legislation depended on his advocacy his voice, vote, or his action. On the other hand, had he been silent or opposed these matters, then perhaps their progress might have slower. And he was one of the founders of Amnesty International, a tireless advocate for European union, and an effective publicist for the British Commonwealth as a model of cooperation. Even more impressive is to know that many of his most compelling speeches were unscripted.

In common with most contemporary biographers, Bloch says nothing at all about religion in Thorpe’s life, though I expect his parents were churchgoers and he must have been, too, as a child and boy. Not quite, there is one reference half way through within wife died and Thorpe spoke of the spirit living on.

There are a lot of might-have-beens in Thorpe’s story. Had he joined Conservative or Labour he would certainly have made it to the front bench and perhaps leadership. Had homosexuality not been illegal and socially unacceptable, he would have perhaps been even more successful as Liberal leader, because hiding his life as a homosexual must have drained a great deal of energy and concentration from his day job, and hiding it finally undid him. Had he followed the advice of several friends to call the bluff of his nemesis and get it over with once and for all even that meant going public, he might have weathered it.

Michael Bloch

Michael Bloch

The book delivers on the potential seldom realised in the biographies of showing that the boy fathered the man. The traits, attitudes, postures, affectations of young Jeremy formed the man he became. Indeed it does that explicitly and effectively.

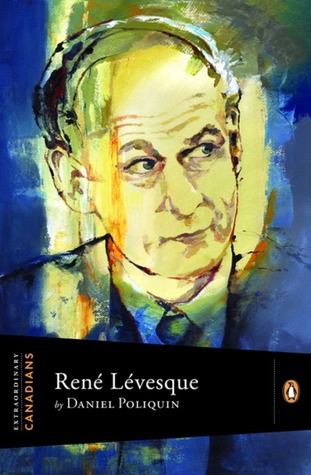

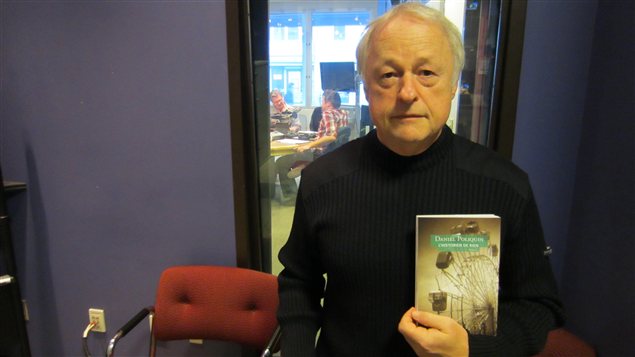

René Lévesque (2013) by Daniel Poliquin

René failed because he succeeded. Ever a paradox.

Many people loved René and many people hated him, and still more both loved and hated him. He is the one person whom I would say was charismatic. He burned with a message akin to those religious prophets that Max Weber coined the word to describe. I saw him once in person in a very small audience in Edmonton, and many times later on television. There are plenty of clips on You Tube. But, well, you had to be there to feel the electricity in the air. At the 1980 defeat the rapturous crowd response and his simple and direct statement: ‘I understand’ perhaps suggest his quality. Remember this is the leader addressing the troops in defeat. It is on You Tube.

The book does not try to be a biography inquiring into the growth and shaping of the man, but is rather a summary of his life and career. It filled in many gaps for this casual observer.

Readers who do not know René can start with the three facts.

1. He was always called René by everyone from bus drivers. journalists, enemies, admirers, voters, opponents, to body guards. Like the eponymous television characters Lovejoy or Morse, René had only one name.

2. When he resigned from office after nearly a decade and cleared out his one bedroom apartment where a plastic milk crate served as a coffee table, he took away his worldly belongings in a plastic supermarket bag. He had long ago given his apartment in Montréal to his divorced wife. (He lived his short years in retirement on his parliamentary pension.)

3. The epitaph from one close and sympathetic English-Canadian observer was: his words stopped more than one riot.

He was from Gaspé, a distant and isolated region where the living is hard, but his family had connections. He was a lousy student and dropped out of Laval University in 1944 for military service. But unlike the Québécois hero of Hugh MacLennan’s ‘The Two Solitudes’ he did join the Canadian army.

René did everything his way: He went south and enlisted as a translator and liaison officer in the United States army serving in Europe with Patton’s Third Army. He saw Dachau within days of it liberation, and that vision stayed with him for the rest of his days. In 1950 he went to Korea as a correspondent, this time with Canadian troops.

Like many, veterans and not, he later embellished these experiences in many ways, but somehow managed to live those fictions down. He did tell lies, to make it plain.

The author suggests three legacies his 1944 experiences that forever shaped the man:

1. Democracy. He arrived in London in 1944 to a society under siege, yet he saw Hyde Park orators excoriating Britain for its coloniziation of India. Here was a country on its knees, everything rationed so thin as not to exist, with nearly every man and woman in a crude uniform – some with wooden rifles, V-rockets falling every day killing thousands, and yet during all-clears polite Indian orators excoriated England to attentive and polite crowds. If that was democracy, it was what he wanted.

2.Les maudits Français. He never had any interest in or respect for France. Later when he met French presidents and foreign ministers, he seldom did more than go through the motions. De Gaulle’s (in)famous remark from the balcony of town hall in Montréal, sent René into a rage. Another Frenchman interfering in something he does not understand. More colonialism!