The last days of a regime.

Regimes come and go. In most places in the world the change is rocky, ragged, and rugged: Mubarak in Egypt, Allende in Chile, Hitler in Germany, Amin in Uganda, Franco in Spain, or Peron in Argentina. Mobs in the streets, armed police off the leash, fires breaking out here and there, hastily packed bags, the Swiss account numbers memorised. It is even more difficult when there is a war on with marauding raids, artillery shells in the air, and masses of troops on the move.

That is the subject of this book, the transition of the government of the Confederate States of America out of existence from February 1865. The hour finds the man, Italians sometimes say, and this hour found John C. Breckinridge who is the major character in this telling.

An honourable defeat, as in the title, would mean the best possible negotiated terms for the men of the Confederate Army and Navy, e.g., that they would be allowed to go home and not be imprisoned or otherwise punished and also that civil order would continue even when the war ended, i.e., that the state governments would continue to maintain law and order, protect banks and private property, dams, bridges, roads and so on. None of this could be assumed, it had to be brought about…somehow. It also meant that the army would not disintegrate into bands of armed men preying on the civilian population.

An honourable defeat also meant that none of the tens of thousands of armed men pledged to the Confederacy would be encouraged by word, deed, or silence to resort to partisan or guerrilla warfare. That is. when the government capitulated, all its loyalists would lay down their arms. There would be no further resistance.

In return for that guarantee there would be no reprisals against individuals. Breckinridge also wanted the units of the army to remain together and march home, i.e., the Fifth Mississippi infantry regiment would march back to Mississippi en bloc and put themselves under the authority of the state government as a militia to keep order, if that were necessary, and the looting and banditry that occurred in Richmond and environs so quickly after Lee’s withdrawal made this a real possibility. Indeed if the units simply broke up individually, the fear was that some would turn to banditry, think of the James brothers. Even those who called themselves partisans would be a greater threat to Confederate civilians than to the Union army, e.g., the James brothers when they rode with William Quantrell.

To bring about an honourable peace was difficult, first, because the elected president of the constitutional government of the Confederate States, Jefferson Davis, did not accept defeat was inevitable. Second feelings ran high after years of death and destruction, would anyone listen. Third, getting any message out was nearly impossible given the destruction of railroad and telegraph lines.

A major part of this story is the intransigence of President Davis for whom every reverse meant only that others had to redouble their efforts and make more sacrifices. Under the blows of defeat, he increasing retreated into a silent shell, but when he did speak it was the same message of more effort, more sacrifice. Even when resistance would serve no purpose he would not accept the personal humiliation of defeat, at the cost of the lives of many others.

During most of the flight of the Confederate government from 2 April to the end of May, Davis was lost in a cloud of despair and denial, leaving Breckinridge to exercise the executive powers remaining to the government. These powers were few but they were not negligible for those affected by them. Chief of these was to maintain social order, but also extended the preservation of and then the orderly disposition of government property. He was de facto acting President.

President Abraham Lincoln had refused to recognise the Confederate Government and he would never treat with it in any way. Yet Lincoln’s murder changed everything, for the worse, and meant that the Federal government was even less likely to respond to any overture from the Confederacy.

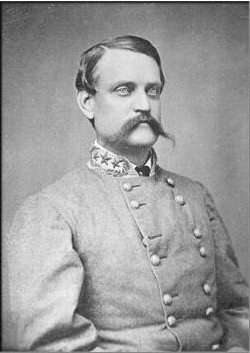

That the result was as peaceful, harmonious, and orderly as it was, the author credits largely to the efforts of John C. Breckinridge (1821-1875). He was a moderate from Kentucky with a distinguished political and military career. After a term in the United States Senate he was Vice-President in the administration James Buchanan (1857-1861). He was a candidate in the 1860 presidential election, one of four, and he won most of the Southern states, and so had a national reputation. After the election, won by Abraham Lincoln with far less than a majority of votes, Breckinridge returned briefly to the United States Senate.

John C. Breckenridge

John C. Breckenridge

He had served in the Mexican-American War of 1846-1847, as did so many other Civil War soldiers did. When the Civil War loomed he was commissioned a brigadier general to raise Confederate troops in Kentucky where his family name was widely respected. During the war he rose in rank to major-general of the CSA and served at Shiloh, Stone River, Missionary Ridge, and New Market. Like everyone who had to misfortune to serve with Braxton Bragg, he was sidelined because Bragg, being one of the few with any influence over Jefferson Davis, convinced Davis that Breckinridge was disloyal. Go figure, after reading that list of battles.

Despite being in sole command at one of the few battles Confederate arms won in 1864 at New Market, he was relieved of command. Then in a desperation move, Davis appointed him Secretary of War. It was desperation because no one else wanted or would take the job, and Davis perhaps thought he knew and could control Breckinridge with threats of censure on the the trumped-up charges Bragg had lodged. In this case as in all others, Davis was no judge of men (and perhaps not of women either). Breckinridge took the assignment exactly because he knew the end of days was coming, and he hoped to see an honourable peace as outlined above, and would work hard and intelligently to achieve it.

While the Confederate government remained in Richmond in February 1865 Breckinridge schemed, planned, plotted, and conspired with likeminded others to pressure Davis to face facts and seek peace. It is both heartening and depressing to see that their efforts were constrained by respect for constitutional provisions setting forth presidential powers, upholding states’ right, making supreme the civilian control of the army, and so on. Breckinridge himself was so rule-bound and though he found others who agreed with him about the need to seek peace now, they were also rule-bound. Still others were unwilling to take a position because they still hoped for some benefit from the situation. Even in March 1865 there were some Confederate Senators who aspired to succeed or replace Davis. The ego drove some to hope to be themselves President of the Confederate States of America even as it dissolved. (Pedants note, Confederate presidential elections were scheduled for 1867.)

But Breckinridge never had in mind a coup d’état which would only create more dissension, animosity, and confusion. He and all he involved adhered to the letter of the Confederate Constitution. While the most prestigious figure in the Confederacy General Robert E. Lee agreed with Breckinridge, this demigod would not overstep the chain of command. He reported to Davis and took his orders from Davis and he would not depart one iota from that, though at the same time he would lay out the unvarnished truth of the situation to Davis in his reports. These Davis would hear in silence and as always thereafter speak of redoubled efforts. Breckinridge spent several twenty-four hour days trying to coax and coach Lee into submitting a written report that implied, if did not say, surrender. Lee would never go quite that far. The conclusions to be drawn from his reports were the responsibility of his political masters.

Breckinridge tried at the same time to put together a coalition Senators and Representatives to arouse the Congress to ask the President to report to it and during the subsequent debate the peace initiative could be raised. He could not quite gain the support of the right individuals or in sufficient number.

He also tried winning over this half-a-dozen cabinet colleagues to speak as one to the President to seek peace. Some were so jaded by then as to be indifferent. Others kept alive their own ambitions, if not to succeed Davis, then to return to a political career in a state. One was a complete David sycophant. To win one man over was to alienate that man’s rivals.

He also tried to find a way for the State Government of Virginia to recall its citizens from service in the Confederate States of America armed forces, thus emasculating them in the East, and then for Virginia to secede from the Confederacy on the assumption that other states would have to follow that example and so bring an end to the fighting. The Confederate Constitution recognised state sovereignty.

To sum up, Breckinridge tried six or more different approaches, singly and in combination, to create a coalition for an an honourable peace in the Confederacy. He tried cabinet. He tried the Senate. He tried the House. He tried the state of Virginia and later North Carolina. He tried the leverage of General Lee’s prestige. He tried, later, General Joseph Johnston’s last remaining army as leverage. He tried some of these avenues more than once and several in combination.

He tried to influence Lee to sign his order of surrender on 9 April 1865 as Commander-in-Chief of the Confederate forces, a hollow title Davis had bestowed on him in earlier. Breckinridge thought that nomenclature would justify the end of hostilities across the board. Instead Lee directed his order to surrender to his field command, the Army of Northern Virginia in his General Order Number Nine. He felt he had no larger authority to dictate to others in Mississippi, North Carolina, or Texas.

That might have been enough to keep a normal man busy, but while Breckinridge was doing all of this, and more, he was also managing the largest, most complex, and important department of the Government of the Confederate States of America, accomplishing feats of provisioning, storage, and distribution that had baffled his predecessors. Lee commented on the irony that his army had never been so will stocked with food, uniforms, and munitions as it was in the last few days of its service. That fact he attributed to the labours of Secretary Breckinridge.

To no avail, and on 2 April, General Lee withdrew the scarecrows of his army from the earthworks at Petersburg and fled south and east to avoid the closing jaws of the Union army. The government now had to evacuate Richmond which was open to Federal assault. Breckinridge had no general authority, but as Davis was nearly comatose with shock, he took it upon himself to organise the selection of archive material for destruction or shipment, the opening of warehouses to distribute the food and clothing that remained, before the Federals arrived and took them, the burning of bridges, the assembly of wagon trains to put the government into flight, and to piece together the railway trains to transport the cabinet and the treasure (perhaps $500,000). He also managed to raise a scratch force of horsemen of several thousand to escort the wagon trains.

By default Breckinridge became the de facto manager of the government’s flight and gradual decay. All the while he continued to search for a way to produce an honourable peace.

Nothing was easy and nothing worked smoothly. When they came at all, the trains were five or six hours late. Roads were impassible in the mud of early spring rains and horses were near starvation to begin with. People got lost in the confusion. Mobs choked streets in fear of the coming Federals. Looters got to work. In the confusion arsenals in Richmond were destroyed, setting fire to much of the city. There were fears and rumours of an armed slave uprising fomented by the Federal cavalry.

Apocalyptic it was.

There was no plan except to get the government out of Richmond. Breckinridge hoped it still might bring an honourable peace, though the capacity to do so diminished with Lee’s surrender, while Davis spoke of, take a guess, redoubled efforts. The merry-go-round stopped briefly at Danville Virginia. The cabinet set up shop in front parlour of a private home. Davis wrote a message to the people calling for…redoubled efforts. Breckinridge gathered intelligence about the armies and tried to find a way to make peace through the state of Virginia or then North Carolina.

Federal cavalry was out in force looking for this government on wheels, and Danville was so obvious a place that burned bridges or no, it had to move on, to Greensboro in North Carolina and on and on further south.

There was no master plan and it was only Breckinridge’s initiatives that kept the wagons rolling. The group started with thousands of men, soldiers and civilian officials, and their cargo and camp followers, and other citizens terrified of rumours of the Federal atrocities (attributed to black troops, who truth to tell were themselves victims of atrocities).

The purpose of the flight changed as time went on from (1) negotiation, (2) maintenance of social order, (3) personal safety and exiles of Confederate Government officials, and (4) to assist Confederate soldiers who had surrendered to get home, (5) to settle the outstanding debts of the Confederate government with that dosh. The disintegration of Confederate armies rendered negotiation moot. Social order did break down. As soon as the caravan left a town, the government stores, offices, and warehouses as other public facilities were ransacked, looted, and pillaged. As word spread of the comprehensive defeat, other civilians took to the hills, partly to escape the feared Federal atrocities and also to escape the likes of Quantrell.

There was never any intention to take the government into exile, though some of its individual members might go into exile to avoid Federal retribution, especially for the murder of Lincoln, which many in the North thought was a Confederate deed.

Breckinridge tried, on the retreat, to preserve War Department records. Those left in Richmond were put into fire proof safes, not all of which proved to be fireproof. As they shed wagons, railway cars, and load, more and more paperwork was left behind. Much of this he tried to leave in the safes of local banks, and in other cases put into chests and buried. In part he wanted the historical record to show what had happened. This accuracy of record became even more important with the murder of Lincoln. He wanted to demonstrate that the were was no involvement of the Confederate War Department.

He also held onto some of the paperwork long into the journey to the annoyance of some in the group because it slowed the pace. Among the papers he kept at hand were dossiers, documents, charge sheets, affidavits, testimony that identified Confederate officers who had committed atrocities, usually on black Union soldiers. While en route he tried to locate one such officer who had killed helpless black Federal prisoners. This had occurred in an area where Breckinridge had nominal command on paper, though he had become Secretary of War and had left the department, his name was still on the letterhead. That made it personal since these murders had occurred in his name.

Breckenridge authorised the dispersement of the treasure along the way to pay off soldiers in the escort, to buy provisions, shoes, and clothes for paroled soldiers trying to get home, and to buy medicine to treat wounded men. He himself took the soldier’s pay of $26.60 out of the hundreds and thousands he had in hand. This was the amount all soldiers. regardless or rank were paid, Several of his cabinet colleagues were much more grasping according to the assiduous financial records kept even on this trail of tears.

The trip goes on and on, as the group splits, and takes different routes. At the end of May after some weeks in the swamps of south Florida, Breckenridge made it to Cuba, His last act as an official was to appeal through the resident American journalists in Havana for all Confederates to lay down their arms and accept the result. After some years in exile he returned to Kentucky and lived quietly, refusing an invitation from President U.S. Grant to re-enter politics. His health had been badly damaged by war wounds and then the diseases and hardships of the flight through Florida.

Early in the odyssey he become the first and only Secretary of War to lead troops into battle when he led the cavalry escort in a counter attack on Federal pony soldiers who threatened the column (p 99). Would contemporary Secretaries of Defense be less likely to put boots on the ground in combat if the boots were theirs? Or their children’s? The answer is obvious: Yes.

Our author says Breckinridge, as a former Vice-President (1857-1861), was the most senior political figure to side with the Confederacy (p 167). Former President John Tyler (1841-1845) did so, too, serving as a Congressman from Virginia in the Confederate House of Representatives until his death.

A stylistic quibble, ’Secretary of War’ should surely be in capitals since it is a title, like a proper name but it is not.

I read this book near the publication date and when the upheaval of moving brought it to light again, I put it aside and dipped in, but once in I kept going since it is such a compelling and fast-moving story with a cast of characters from the ever-smiling in the face of adversity Secretary of State Judah Benjamin, the taciturn President Davis, the demigod Lee, the clever temporiser Joseph Johnston, the man of the hour Breckinridge, and many lesser known figures who rose to the occasion.

William Davis

William Davis

One such instance of rising to the occasion occurred when a month into the flight, Davis summoned the brigade commanders of the 2,500 escort troops to an audience. When they assembled, Davis spoke of redoubled efforts and still more sacrifices as they stood in dumbstruck silence. Davis expected them to salute in agreement. He did not assemble them for advice or debate but to agree with him and to obey.

As the silence prolonged, he finally asked them to respond. To his credit, the senior man of the five brigadiers, George Dibrell, stepped forward and said it was hopeless situation and useless to ask more of his men who had continued this long out of personal loyalty. In turn, the other four concurred. Davis paled, and as always when confronted with contradiction went into his shell. There was more silence. Finally, Davis’s manners returned and he dismissed them only later to bemoan their lack of resolve. All praise to General Dibrell for calling a halt to the madness.

Skip to content