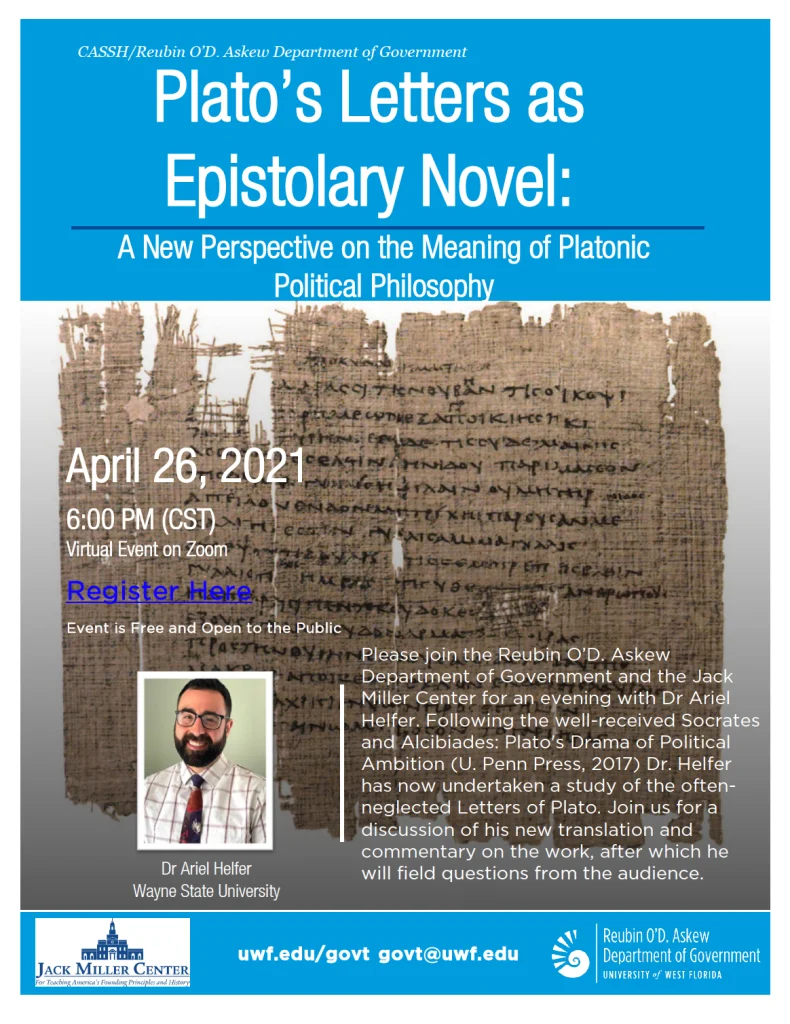

Plato’s Letters: The Political Challenges of the Philosophic Life (2023) by Ariel Helfer.

Good Reads meta-data is 301 pages, rated 4.0 by 2 litizens.

Genre: Straussian.

Verdict: Never has so little been made into so much.

Tagline: If you don’t know you cannot be told and if you know you don’t need to be told.

Leo Strauss (1899-1973) educated a well defined cohort in political theory in his years at the University of Chicago. He himself published a series of books that spelled out and exemplified his approach to interpreting texts, and his acolytes, while competing among themselves with the usual academic undermining and backbiting, continue the tradition to this day.

The north star of Straussianism was that great thinkers hide their meaning from both the oppressors and the masses, and these two can be one and the same. Ergo: meaning is hidden in plain sight in the text.

It takes an Indiana Jones of the seminar room to find this meaning, and avoid the snares and blind alleys left for the unwary. To find the way Jones first must study the explicit words of the great mind. That means learning the language used: ancient Greek, Latin, Italian, German, or French, and so on. One must acquire this tool before proceeding.

Next one must enter into the psychic world of the author by studying the context within which he (yes, they are all men) wrote.

Accordingly, there is a long apprenticeship of devotion to the task to be performed.

While great minds may be prolific, everything they wrote forms, if properly decoded, a single text. Note that the process is decoding, not just reading what is on the page but sensing the context in which it was put on the page and – even more important – noting what is not on the page to find what is implicit. Yes, as in aboriginal astronomy the key often is what is not there. If a reader sees a mistake in the text, the fault is in the reader not the author. Think again. Why would a mistake be deliberately inserted? Is it a red herring to distract the unworthy? If something is not there, stop and think, and think again. If it should be there, there must be a deep and dark reason why it is not. Look for the clues. Absence may be evidence.

The single text is like an old dark house where a hidden sliding door set into a wall leads to passageways built into the fabric of the building that Jones using the light of a Straussian lamp navigates step-by-step. Legend has it that some of Leo Strauss seminars spent a semester of twenty plus class hours pondering, often in Quaker-meeting silence, a dozen lines from a Platonic text. Tin foil hats were optional.

If the coded passageways twist and turn that is not an accident or a compromise with the circumstances, still less a mistake, but profoundly intentional. Great minds do not make mistakes or have accidents. Homer did not nod. Everything that is there is meaningful, however specious it seems on the surface (to wit, many of the preliminary arguments in Platonic dialogues are not chaff, warm-ups, or false starts but may be the real message encrypted for Jones to fathom). Moreover, what is not there may be even more meaningful than what is there.

The pièce de résistance is the numerology. Word, page, chapter counts and numbers themselves bear significance in this approach. The seventh word in the seventh chapter must be interrogated with Gestapo thoroughness. An old favourite of this kind is Leo Strauss’s expressed amazement that Machiavelli’s Discourses has 142 chapters, exactly the same number as Livy’s History of Rome. Astonishing! Is it? The Discourses is a chapter-by-chapter commentary on Livy’s History so it almost has to have the same number of the chapters. Thus does the Straussian endow the mundane with mystery.

As regards Plato’s Letters the chief argument of this book is that the letters are to be taken together as a single text, not a scattering of remnants. This is partly proven by the fact that there is nothing in them to indicate that unity, no cross references, few if any continuities. It is a hidden single text that only an acolyte will detect. Likewise, the positioning of the letters in the count strikes another Straussian chord. There are thirteen letters. That cannot be an accident. The longest and most significant is number seven. Again no accident.

This veneration of the text, one might think, is compromised in ancient authors like Plato because we have no original texts, but the Straussian thesis is that such genius as Plato’s prevails against the ravages of time and tide and translation from Ancient Greek into Arabic then Latin then later Greek then modern Greek then English for the masses. (Ancient Greek is to modern Greek as Old Norse is to contemporary English, I have been told.) Yes, the fog descends at this point but the momentum continues. For an outline of this approach I have tacked on at the end the notes I used to discuss this method with students in days of yore.

In most of the letters Plato is replying to someone who has asked his advice on what to do in a political situation. While the book runs to three hundred pages, its interpretation of Plato can be summarised this way: there is no point in offering advice because all existing polities are corrupt. This is true by definition because all that exists is frangible. Any advice would be corrupted and so serve no purpose. It takes 300-pages to air that less than nourishing conclusion.

Given the Straussian emphasis on context it is curious to note that in the discussion of the minute detail of Plato’s visits to Syracuse, the author makes no mention of the last time Athenians went to Syracuse in the Sicilian Expedition of 415 B.C.E. a generation earlier. It is all but certain that relatives of Plato’s took part in that debacle. But then Alcibiades, a leader of that expedition, is not mentioned in the text either, yet his name is on two alleged Platonic dialogues.

How do we explain spurious letters or other texts attributed to ancient writers like Plato? There was an incentive to forge letters in ancient world to sell to private collectors and to the libraries at Alexandria, Pergamon, and Byzantium and when these libraries fell down the memory hole, a quick and clever forger would turn out a letter that had allegedly been saved from the ruins and put it up for sale. Of course such creativity was not limited to letters. It may be the source for the spurious dialogues, essays, and plays attributed to Plato, Xenophon, and others. But short letters were the easiest to prepare and did not require much intellectual input. They sell on their provenance, not content.

….

How to read a book in the Straussian way.

First make explicit the assumptions naive readers make.

1. the text is accurate and complete as the author could make it.

2. the text conforms to the author’s intentions.

3. the author wrote freely, uncensored.

4. the unit of meaning is the chapter, paragraph, page, and line

5. the meaning is in the words used.

6. the author is trying to communicate with any and all readers.

7. errors, omissions, contradictions are errors, omissions, and contradictions. They may be explained but they have no meaning.

8. purpose of writing is to test arguments and propositions, and to persuade.

In contrast Straussian reading assumes:

1. There are Great Truths. The esoteric. Like the statue in the block of marble, they have to released.

But they cannot be explicitly spoken. Why not? Because they would infuriate both the elite and mass, because the elite is corrupt, and mass is inferior.

To speak the great truths would both shake the polity and so endanger the speaker.

2. Therefore the Great Truth sayers are always persecuted and censored. They react accordingly.

3. Great Minds know the Great Truths, and they know persecution prevails over Great Truths.

4. Great Minds elude persecution in writing Great Books.

Indeed, persecution is a necessary condition for writing a Great Book.

5. Great Books publicly deceive; they deceive censors and the censorious part of each reader.

Privately, between the lines, the Great Books carry a coded message to informed readers.

Great Books combine the advantages of general communication for being widely available but avoid the threat of censorship and danger with the advantages of private communication carrying a frank and important hidden message to select readers.

6. Great Books reveal themselves to Great Readers who:

– are careful for everything in a Great Book has meaning.

Everything. What is said and what is not said. What is there and what is not there.

– interpret not just each passage alone but each passage in the context of the work, and the life work of the Great Mind.

– read between the lines, giving meaning to silences, i.e., what is not there.

– realize that a Great Mind may repeatedly say A is B but mean by that repetition for the reader to conclude that A is not B.

– apparent errors, omissions, and contradictions are intended to encode the secret message.

– look for irony in things said but not meant. Thus is Plato’s repeated assertion that women equal men is dismissed as a joke.

- Divine that brevity may be a form of emphasis.

- perceive that the coding may be within the structure, the middle line, etc. Hence the numerology.

See Leo Strauss, ‘Persecution and the Art of Writing’ (1941) for details.

- —

This lengthy addendum is one reason why I don’t often comment on vocational reading. I get carried way.