When he retired William Lyon Mackenzie King held the record for the longest serving prime minister in the English-speaking world, exceeding the record then held by Robert Walpole, in all 21 years. To put that in perspective, note that Australia’s Robert Menzies had 18 years and Franklin Roosevelt 13, and Churchill 11. In addition, King was the leader of the Liberal Party for a total of 28 years. I expect he still does hold the record for longest serving party leader, too.

William Lyon Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King

Roosevelt had a charm even over the radio and daring ideas, Churchill could wake the dead with his rhetoric and was willing to try almost anything, while Menzies exuded confidence and calm. King had none of these assets. He was short, round, and pudgy. He had no love for meet-and-greets. He spoke in a high squeaky voice that sounded worse on radio than in person though it sounded bad then. He invariably read his speeches word-for-word badly. He had no electoral coattails to make backbenchers beholden to him.

Then why did he succeed? The short answer was said in an obituary ‘He divided us least.’

The legends of King are many, and most have to do with inaction: he never let his left hand know what his left hand was doing, he never did by halves what could be done by quarters and he never did at all what did not have to be done. Like a duck holding place against a tide, he paddled furiously below the surface while doing nothing up top. That image is from Churchill in another context but it fits King perfectly.

It is said that he had all cabinet ministers sign undated letters of resignation as a condition of being named to cabinet and that he kept those in his pocket in parliament during debates or question time occasionally bringing one or all out onto the desk as though about to date a resignation and by this means stimulating his colleagues to fervour. This book does not mention this last story and rather emphasises the care he generally took in stroking the egos of those around him in his earlier years, but it is also clear that he changed over the years, and grew ever more determined to hang on. Still he had plenty of wiles, like calling an election in the speech from the throne! Students of parliamentary procedure will realise how startling that would be.

In his youth, before the concept existed, he became an experienced and successful labor-management mediator in some pretty difficult circumstances. His approach was to get the parties talking, sometimes about trivial things, like where to meet, the shape of the table, and the like, to get them into direct dialogue about something, anything concrete. All the while he would present the factual context and try to get them to agree to the description of the situation. In this effort he was deferential, polite, patient, and had an iron butt to see the job out no matter what.

He was headhunted into politics when a PhD student in economics at Harvard. He entered parliament and became Canada’s first minister of labor in one swoop. His mentor was Wilfred Laurier of the $5 bill made famous in tribute to Mr Spock in 2015.

In office he championed social welfare measures but never tried to push ahead, always waiting for the community to accept such measures as child bonuses, pensions, and so on. His touch in these judgements was sure though there is no telling how or why he had it, since he seldom left Ottawa and when he did, he avoided voters as much as possible. In the few campaign rallies where he spoke he entered by a backdoor, read his leaden speech, and left. With experience he became a more accomplished speaker but never in the same league as his contemporaries, Churchill and Roosevelt. Canadians could hear both the latter often, and King did not try to compete with them.

His reluctance to push ahead irritated many who urged prompt action to use the votes he had in parliament, but King never hurried. Never. The votes in parliament were necessary but what was sufficient was the mood of the country, and divided Canada has many moods, all at once. For example, to some child bonuses were paying Catholic Québécois to procreate.

Divisions! Plenty of those. The prairie provinces are alienated from Ottawa. Not to be outdone the left coast of British Columbia is even more alienated. The impoverished Atlantic provinces are home to the forgotten people. Prince Edward Island cannot be found on some maps of Canada. Quebec is a world unto itself outside Montréal. Labrador and the Northwest Territory are on the dark side of the moon. Ontario owns most of the country. Federal elections were won and lost in the Ottawa River valley, i.e., Ontario and Quebec.

King became leader when he was the rising man, and also at a time when the Liberals seemed certain to lose and none of the other likely candidates wanted the job. He got it, and he kept it.

Many winners are born lucky in their opponents, and King certainly was. The Conservatives found one way after another to alienate vast sections of the electorate, usually by preferring Ontario’s interest to the exclusion of the rest of the country, and making no effort in Quebec which was ceded to the Liberals. In effect, the Liberals were the only national party (sound familiar?) in Canada for much of this period, getting votes and seats in every part of the country. There were elections in the only Conservative seats were from Ontario with a very light sprinkling from nearby Manitoba.

Having observed Laurier, King determined to keep Quebec Liberal at all costs. He did this by finding a loyal lieutenant, first Ernest Lapoint and then Laurier St. Laurent (who later succeeded him as leader and prime minister), to concentrate on Quebec. King pretty much gave them a free hand. He seldom went there, spoke no French, and viewed Catholicism with suspicion.

Over the years there many remarkable events, among the most outstanding were these.

First, the Bynge Affair. As the incumbent prime minister he was at loggerheads with the Governor-General after an election produced no majority. The Liberals lost a substantial number of seats and the Conservatives won many new seats but neither had a majority. The convention would have been that King resign and step back and let the Conservatives form a government, but he hung on for weeks and argued the point with Governor-General Bynge ad nauseum. He finally did resign and the Conservatives tried and failed and a new election followed where King secured a thin majority. Why he protracted the matter is hard to fathom and the author can only say that he was a selfish man, hardly a satisfactory explanation, since King was smart enough to know what he was doing, but what was he doing? King had predicted that the Conservatives would fail, indeed he told that to the Governor-General as a reason why he should stay in office, but he would not back his judgement until pinned to the wall.

Second, King advocated a Canadian foreign and defence policy so did not agree to accept all British decisions or recommendations. Unlike Australia’s Robert Menzies, he did not participate in the Empire War Cabinet in World War II. Instead he said Canadian decisions will be made in Canada by Canadians in the interest of Canada, spending very little time in London, again unlike Menzies. This line outraged the Canadian Britophils, especially in British Columbia which has long lived up to the first part of its name, but it soothed Québécois. It did not satisfy anyone but it did not completely alienate anyone either.

Third, though he advocated unemployment relief in principle, when the Great Depression hit he was unprepared for the magnitude, and he did not warm to John Maynard Keynes’s approach to government budget deficits. Moreover, he was rude and crude publicly in his reaction to protests. No man of the people was he. Moreover, he refused to let the federal government cooperate with the provincial governments held by Conservatives, a sorry example of vindictiveness replacing compassion. Not one dollar to those provinces which hath sinned against Mackenzie King! He lost the next election and found opposition dead boring, leaving the running to others. In a way this loss was lucky for King and for the Liberals because it left the Conservatives in office in the teeth of the Great Depression, and so left them to carry the opprobrium for not combatting it.

Four, there is no doubt his crucible was World War II and conscription. In World War I Canada had poured men into the Western Front, and had taken a perverse pride in the lists of dead. The drain on manpower was incredible, and Laurier slowly and reluctantly accepted conscription. While English Canada was ready for it, Quebec was not.

A brief aside, Québécois speak French but have no love for France. Like the Boers of South Africa who speak a Dutch, they feel they were abandoned by their country of origin, traded away at a conference table. At times Québécois think of themselves as Normans abandoned by Parisiennes.

Laurier legislated conscription in 1917 before the USA entered the war and it led to riots in Montrėal and produced few Québécois soldiers but much ill will. King wanted no repeat of that. His line, which pleased neither the zealots for Britain, nor the Québécois was no conscription unless necessary and conscription only if necessary. It had no ring to it. But if it did not please either camp, neither did it fatally alienate either camp.

In 1944 the Canadian army wanted men to replace its battle losses, including 2,000 at Dieppe which is barely mentioned in this book. But after the middle of 1944 the outcome of the war was inevitable and King would not budge, despite the pressures brought to bear from generals, Liberal backbenchers and ministers, the press, the opposition, and the British and American allies, he held firm. One argument for more troops was that a greater commitment would give Canada a larger role in the peace that followed, say at the United Nations. King had no interest in such aggrandisement. The price was too high. Conscription in July 1944 when the war was all but won in Europe, and Canada had little interest in the Pacific War, would have produced a rupture with Quebec, and would have jeopardised the Liberal lock on it.

While he held off those who wanted more troops he was calm up top, furiously paddling down below.

Five, in the post-war period when a Soviet defector revealed a spy ring in Ottawa, King smothered it, at least compared to the way similar revelations in the United States and Australia were fanned into flames. Those implicated were pursued but he did not try to exploit it with the electorate though that was urged on him by many associates. As always he preferred the minimum, not the Aristotelian mean, the absolute minimum.

In his personal habits he was notoriously frugal and recorded, in the best Scots tradition, every penny he spent. This personal frugality carried over into a reluctance to spend government money. Even for cherished projects like unemployment relief in the Depression.

He never married though many women were courted in his early life, none quite made the grade. There is no mistaking his loneliness in his mature and later years, though our author is insensitive to it. That he was a bachelor was an oddity, for then as now, the norm is that the democratic leader to be a normal, married man, façade though it may be. The exceptions are few and none with King’s endurance.

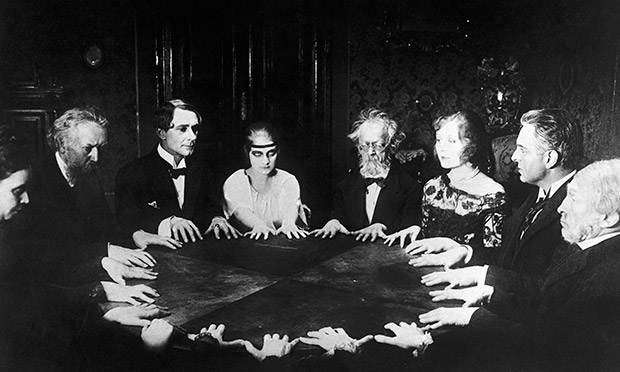

Stranger still was King’s life long obsession with spiritualism. The author has many derogatory things to say on this subject and only grudgingly notes that spiritualism had a following among many educated and intelligent people at the turn of the twentieth century. King attended sėances, consulted fortune tellers, had tea leaves read, and so on, all this meticulously recorded in a diary he kept all of his life, writing 5, 10, 15 pages a night in long hand which he had typed and filed each morning, leaving behind a houseful of boxes and binders of this diary.

Yes, Prime Minister!

Yes, Prime Minister!

He never seems to have read a book or listened to the radio for amusement or relaxation. His only relief from duty, apart from his love of dogs, was this diary. His only companion was a dog, three Irish setters, one after another.

Even more unusual is his near childlike belief in an enchanted world where a cloud formation foretold events, or a draft that blew a paper to the floor was a sign. Everything that happens, and I mean everything, from leaf drops, to birds in the sky, they were all communications of meaning which he recorded in his diary, linking the cloud shape to his decision to appoint X to this or that post. He confided these enchantments to his diary and did not tell X he got the job because of a cloud looked like him!

King combined this spiritualism with a Christian duty to serve mankind. The book is silent on his church-going habits and how he squared what he heard in church with his spiritualism. By the way the focal, but not exclusive, point of his spiritualism was his mother, giving the pop psychologists much fun. Our author has no feel for religion in one’s life and treats it as a hobby, one that is less amusing than the spiritualism.

As he aged King became a tired old man who took out his aches and pains, and loneliness, on his staff. He worked many to the bone, and some to death, and seldom thanked any of them. There is megalomania in all that. It is always about King. When a subordinate dies at his post doing his bidding, King’s first reaction is irritation that the chap let him down.

His name needs explanation: William Lyon Mackenzie King was the maternal grandson of William Lyon Mackenzie, himself a formidable figure in Canadian history and politics. It was his mother’s father’s example that led him into public life, and it was an inspiration he acknowledged now and again over the years in stressing his sense of duty. The author has hard time playing this with a straight bat. There are enough cheap shots in this book to please Bill Bryson.

The book has had many accolades. This reader will not join the chorus. I found the writing sloppy, the organisation repetitive, the analysis of King’s political successes and accomplishments just greater than 0. Instead there much sneering at the spiritualism, again and again, meanwhile accepting events as inevitable rather than examining the dynamic that brought them about. While the author notes King’s enormous capacity for delusion, he accepts most of the factual assertions in King’s voluminous diaries, seldom seeking confirmation from another source. Contrast this approach to Robert Caro’s Herculean double-checking in his biography of Lyndon Johnson. Most of King’s delusions stemmed from the enchanted world he inhabited, which often made him seem to be central figure. If Churchill wrote him a letter about some routine matter that was conclusive proof that Churchill admired, respected, and was influenced by him.

Allan Levine

Allan Levine

Explanatory note. Above I have referred to Québécois and not French Canadians. Many French Canadians live outside Quebec and they seldom identify with it and its causes.

Category: Presidents

Huey Long, ‘My First Days in the White House’ (1935)

It is now commonplace for presidential candidates, even early in pursuit of party nomination, to publish a book. Most of these campaign books are autobiographical of the ‘My Story’ sort. John McCain offered ‘Faith of My Fathers’ (2000) gently reminding readers and reviewers of his sacrifices. Mitt Romney in ‘No Apologies’ (2010) tried to make himself seem ordinary but special at the same time. Barack Obama in ‘The Audacity of Hope’ (2008) and Hillary Clinton in ‘Hard Choices’ (2014) have bowed to the convention. A host of lesser known candidates have had their ghost writers, too, briefly putting their names before the reading public in book stores. (As always, Hillary overachieves and has several other titles to her credit.)

In the current fashion these books emphasise the intangible, the character of the candidate. Seldom do they focus on problems, programs, or goals or have the intellectual content of, say Richard Nixon’s ‘Six Crisis’ (1962).

When the campaign book became an essential is hard to say. Since the 1960s it has become a fixture. Semi-literate candidates who have never read a book, now write one!

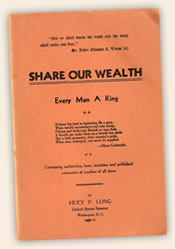

In 1936 a campaign book was not commonplace; Long’s ‘My First Day in the White House’ was unusual in its time and place.

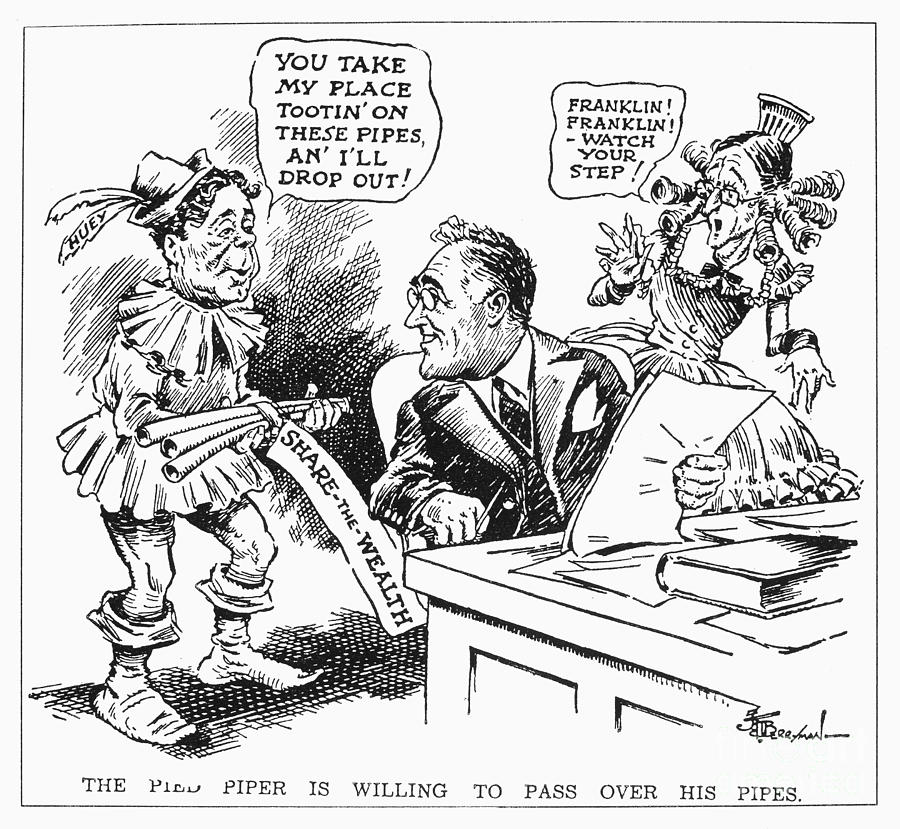

Long’s plan was to support an independent spoiler (Father Coughlin) with no chance of winning in the 1936 campaign to split the Democratic vote and elect a Republican, who would be unable to respond to the Great Depression, leaving the Republicans discredited and the Democrats without a leader by 1940 and the country desperate. Then Huey P. Long would accept a popular draft to take the Democratic nomination. During his short time in the United States Senate Long had begun to organise the spontaneous draft that was supposed later to impel him to the Democratic nomination. Huey never left anything to chance and he worked for the longer term.

This book, incomplete at his death, was a declaration of his intention. The custom at the time was for senators to declare their candidate for a presidential nomination at a press conference in the Senate cloakroom. Never one to follow form, Huey Long did it in this book.

In the hectic life he led, Long dictated this manuscript in 1935 in Washington D.C. where he was a senator from Louisiana, and Baton Rouge in Louisiana where he ran the state through a stand-in governor, often in cars, taxis, and hurrying from one meeting or speech to another, and on the train on his national campaign for his ‘Share our Wealth Clubs.’ He worked 24/7, getting by with four hours sleep most nights.

Long had one simple proposal that the ‘Share our Wealth Clubs’ expressed. Tax the rich! TAX the rich! TAX THE rich! TAX THE RICH! Get it?

It is more than taxing income, by the way, it is was also seizing the fortunes the rich had already amassed. The word ‘confiscation’ was not used but that it what it was. Compared to this spectre, Franklin Roosevelt was a bastion of the establishment.

But what of the book? It has an impish humour that is attractive, and a subtlety of mind and insight into the motivations of others with which he is seldom credited, but which he must surely have had to be as successful as he was. Like many other successful politicians he understood what motivated his opponents and how to manipulate that rather as a sailor learns to tact into the wind.

In these pages President Long hits the ground running, publicly naming a cabinet on inauguration day without bothering to inform those named! It is just what he would have done. He named, among others, Herbert Hoover to Commerce and Franklin Roosevelt to Defense. They could of course decline, but then they would have to explain to public opinion why they refused to serve their country in these roles! Now that is audacity. Needless to say in these pages, they comply with that great god public opinion in the person of its prophet Huey Long.

The millionaires resist but are won over through appeals to their better natures, long term self-interest, and Christian charity. That Baptist ascetic John D. Rockefeller was the first to surrender his fortune to the greater good. His fortune is a pittance compared to J. P. Morgan or John Hill but they, too, succumbed to saviour Long. In short order. Morgan and Rockefeller are redistributing their wealth and ohers’ in a ‘Leviticus’ jubilee.

The only tension is this parable occurs in Chapter Six when an unnamed governor stirs up popular resistance to Long’s initiatives. Long does what Huey Long always did, he goes to face down the crowd, and wins them over. The governor is contrite, saying he led the revolt, to force the Supreme Court to rule on Long’s many initiatives, which it did found and them all good.

The initiatives include nationalising the railroads (calling William McAdoo from retirement to reprise his World War I role as Tsar of the rails), endless funding for agriculture, education, and health, combined with a balanced budget (thanks the confiscation of the fortunes of the Robber Barons). After token resistance, everyone agrees with Long’s vision.

Most of the book is told through dialogue in meetings or letters. There are illustrations he commissioned as the work evolved. This one for example.

There is none of brow-beating, blatant bribing, sale of offices, strong-arm tactics, double-dealing, and threats, or beatings that fuelled his gubernatorial administration in Louisiana in these pages. It is a redeemed Huey that figures here now that he has ascended to the White House.

It is easy to parody the book these generations later, but in the late 1930s with the Dust Bowl suffocating six states, thousands displaced through foreclosure, hundreds of thousands of jobless men wandering the country, hardship without end for a decade, and against the backdrop of President Roosevelt’s tentative first efforts, placed within the organisation of the ‘Share our Wealth Clubs,’ the book would have been a lightning rod for both hope and despair, one that Huey Long would have wielded expertly. Of that there is no doubt.

The book offers a complete social vision, albeit supeficial, as naive and as inspiring as many utopian fictions. It shows the working out of the idea without any of the inevitable reaction, undermining, half-heartedness, and confusion of life. It compares to Edward Bellamy ‘Looking Backward’ (1888) or William Morris’s “News from Nowhere’ (1890).

‘Kirby Smith’s Confederacy, The Trans-Mississippi South, 1863-1865’ (1972) by Robert Kerby

Class, time for another quiz. Get those eggheads ready! Agitate those little grey cells!

In the 1860s, who…

1.negotiated treaties with foreign governments and corporations without any political authority?

2.created an elaborate parallel federal bureaucracy with no constitutional authority?

3.practiced state socialism?

4.monopolized trade?

5.seized private property to the tune of $30,000,000 in gold?

6.exercised the executive authority of a president without any political mandate?

7.abrogated habeas corpus in the pursuit of conscripts?

8.and did all of this over the area of Missouri, Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, eastern Kansas, and Oklahoma to the loyal supporters of the Confederacy?

All those who said General William Sherman in his famous March to the Sea, on with the dunces’ caps and look at a map!

All of this was done for more than two years (1863-1865) by forty-year old full General Kirby Smith, of the Confederate States of America army. How that came to be, why it happened, what he did and how are laid out in this fascinating study of a corner of American political history quite unknown to this casual Civil War buff.

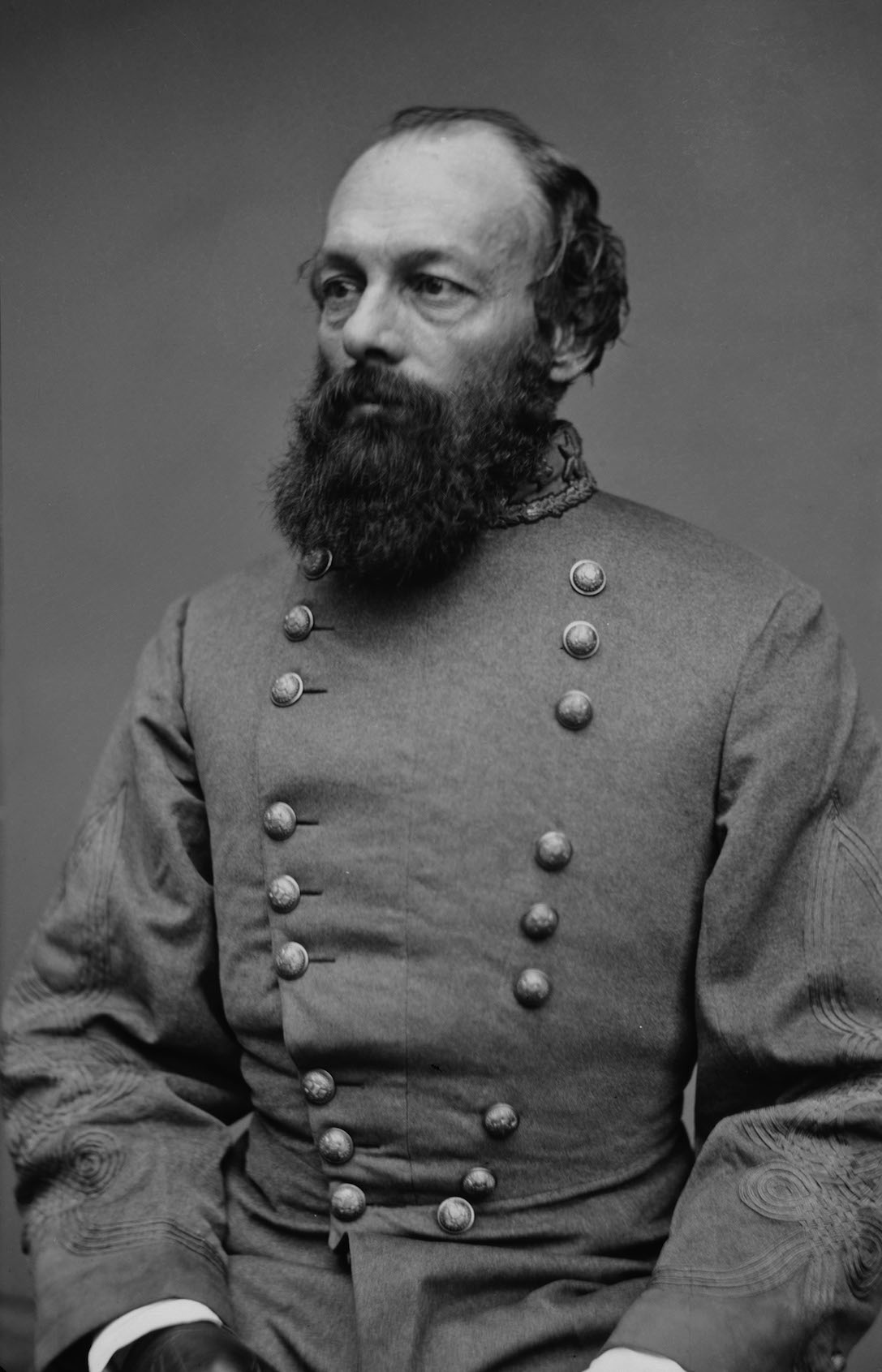

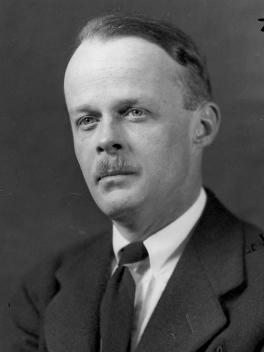

General Kirby Smith

General Kirby Smith

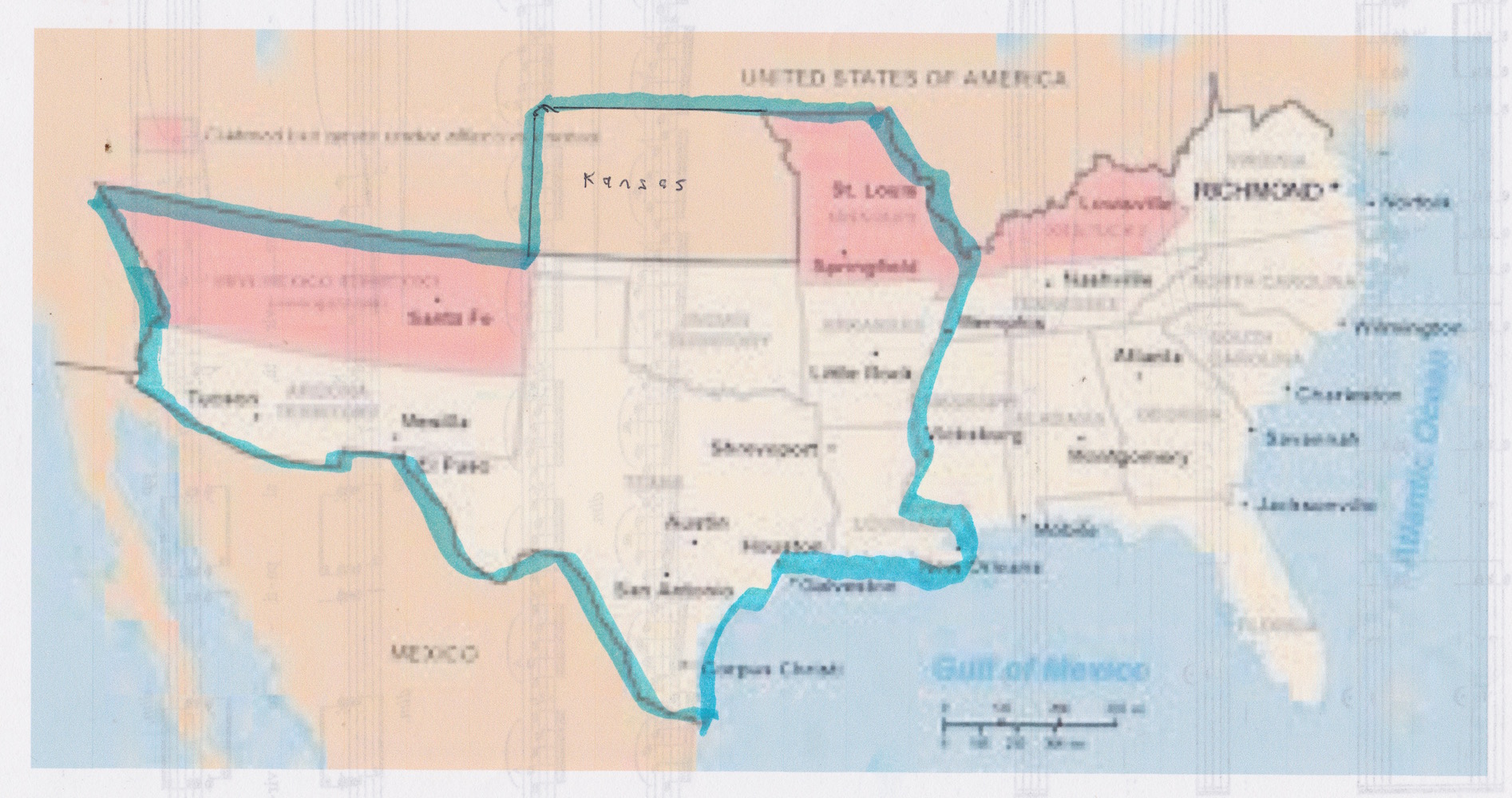

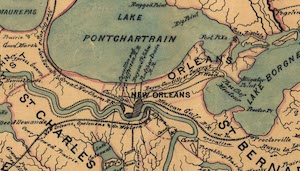

I had long known that the youthful General Smith had commanded Trans-Mississippi Confederacy though I was never quite sure I could find the Trans-Mississippi on a map. I now know it comprised four states (Missouri, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas) and four territories (Arizona, New Mexico, Kansas, and Indian [Oklahoma]).

The blue line encompasses the field of operations of the Department of Trans-Mississippi Confederacy.

The blue line encompasses the field of operations of the Department of Trans-Mississippi Confederacy.

His army, such as it was, was the last major force to lay down its arms in June 1865 as the news from the east made its way west. But knowing that was to know nothing of the detail.

After reading some other biographies of presidentials in the Civil War period I was reminded of Smith’s domain and decided to find a book about it. Pay dirt!

Not only does the book produce the goods on Smith and the Trans-Mississippi it makes the point that without the title or the legitimacy that goes with it, he exercised the prerogatives of a super-president unbalanced by a legislature and unchecked by a judiciary for two years. See that list of eight points above. If President Abraham Lincoln or President Jefferson Davis had done any of these, the opposition would have been great. Indeed, for what it is worth, Davis did none of them and Lincoln did only one, habeas corpus – he put a lot of people in jail indefinitely on the suspicion of sedition without trial. A lot. He provided a precedent for George W. Bush and Guantanamo Bay that was never cited!

First to that name ‘Trans-Mississippi’ for those who did not read Caesar’s ‘Gallic Wars’ ‘Cis-Alpine’ means on this – ‘cis’ – side of the Alps, and ‘trans’ means…? Yes, Class, on the other side of the Alps. Now apply that to the Mississippi.

No, Dunce, Caesar did not cross the Mississippi River at Rubicon! Do pay attention.

Cis-Mississippi is east of the Mississippi River and Trans-Mississippi is west of the Mississippi River. (Except in Des Moines Iowa where I repeatedly find on Skywalk maps that east and west are relative terms not fixed.) Now that we have nailed the name, let’s go to the man.

Kirby Smith (1824-1893), born in Florida, was a West Point graduate and a gentleman scientist whose collection of botanical specimens acquired while serving in frontier forts in Texas can still be seen in the of Natural History on the Mall. He served under Braxton Bragg in the Confederate Army of Tennessee and when his accomplishments made Bragg look bad, he removed him from command in one of this many fits of jealousy. Smith was thus available at the right time to go West in January 1863. The theatre he commanded was the biggest in space assigned to a general officer in either army and the means he had to defend it ranked the smallest on any measure. He said he liked a challenge, and off he went with a devil-may-care wink.

Within six months it got a harder. The Confederate stronghold at Vicksburg surrendered and in a few weeks the Mississippi River became a Federal lake, impassable to Confederates. Smith was now on his own, with very limited, very difficult communication with the Confederate government in Richmond. Intrepid individuals rowed skiffs, canoes, rafts, and logs across the Father of Waters bearing messages. They might wait weeks for Federal patrols on the River to move on, slacken, or be called away to a diversion before daring a night crossing. Anyone who has seen the current in the Mississippi above the Delta knows that this is a life-risking exercise. Many messages and some messengers were lost to the River, to Union patrols, and to self-preserving second thoughts.

At first Smith dutifully asked for instructions case-by-case from Richmond but after July he sought a carte blanche which in a series of agonising messages travelling this long, dangerous, uncertain route from Richmond to his headquarters in Shreveport Louisiana or Marshall Texas President Davis did not say ‘no’ to the request but then did not say ‘yes’ either. For equivocating, President Davis could give the Japanese lessons.

Finally, Smith just focused on Davis’s sentences that seemed to authorise him to do what Smith deemed necessary and ignored all the qualifications, asides, limitations, hedges, cross-references, hesitations, definitions, and the fog of indecision that Davis’s pen exuded. One reason Davis obfuscated was that he, as President, did not have the powers Smith wanted to exercise, a fact of which Davis was made constantly aware by newspaper editors, Confederate Congressmen, and state governors who enveloped him.

Smith’s forces were desperately short of war material (ammunition, firearms, gun powder, pack animals, cannon, shot and shell, uniforms, boots for the men and shoes for the horses) but most of he was short of men. Periodically he would launch an enlistment campaign offering such inducements as he could (immediate furlough and an enlistment bounty in worthless Confederate dollars). Desertion was astronomical, one division reported 300 men fit for duty and 4,500 absent without leave. To stop that he would take troops from contact with the enemy and set them to find deserters who would then be shot on the spot as a lesson to others. This was hardly an appealing duty and members of those patrols often themselves deserted. It was a downward spiral.

The best way to avoid conscription was to enrol in the state militia (which remained true during the Vietnam War; think George W. Bush). The state militias’ registers were bursting with names and for each name there was an exemption. None of the states had the capacity to arm these militiamen with any more than the farm shotguns they brought with them. Few states had officers who could drill and discipline them, and since the officers were elected (per the state constitutions), any officer who tried too hard was defrocked. Moreover, a state militia cannot go outside the state (again by the state constitution), limiting cooperation with others to nearly nothing. While Smith’s armies regularly opposed forces four or five times larger, vast numbers of able bodied men of soldierly age had their exemptions, and these very same men urged Smith to fight to defend their homes and property (slaves) from the Yankee scourge. It did not take long for this circle of irresponsibility to wear out Smith’s good humour. With no legal or political authority but the weapons of his press-gangs, he forced militiamen into the ranks. Of course some of them deserted and sicced governors and newspaper editors on to him, and a host of trial lawyers brought endless suits. He persisted with some success.

To pay his army, to pay civilians for their labor as teamsters or ditch diggers, to buy uniforms, ammunition, and everything else he need a source of such goods and he needed money. The source was obvious. Look at the map above. México! There were plenty of Méxican entrepreneurs to supply whatever was needed. Then the problem was the Readies to pay for it. The only resource of value he had at hand, and he had at hand plenty of that, was cotton. In warehouses, on farms, in sheds there were hundreds and thousands of bales which had built up when the Union occupation of New Orleans stopped the trade through that port. Those who owned the cotton would not, however, sell it for Confederate dollars. Smith tried bonds; he tried his own warrants; he offered interest on the Confederate dollars – no sale!

What was a general to do?

He seized it. In some operations 60,000 bales were impressed by his troops in one day. ‘Impressment’ is the fancy word for stealing with a gun in return for a chit of paper. Get this in perspective, the price of cotton on the world market was very high. One or two bales would be worth a fortune to a private solider. Yes, there was private enterprise among the ranks and not all the cotton seized entered the lists on Smith’s accounts. Even so, in one calendar year he sold cotton for $30,000,000 gold dollars in México. By the way, there is no evidence, none, that Smith enriched himself in this trade.

Cotton bales

Cotton bales

He started shipping cotton to México under armed escorts (yes, some owners formed posses and came after their crop) and he was in business. He created a Confederate Cotton Office and this bureaucracy identified, compensated (seized) crops, stored, shipped, and sold it. To do so it acquired (seized) wagons, mules, harnesses, reins, and teamsters (who were conscripted on the spot). States’ rights, habeas corpus, private property did not figure in the equations. His assertion of authority went beyond even presidential powers.

In addition, to keep the wheels turning on this enterprise much was needed, wagons, wheels, tackle, yokes, horse shoes …. Smith set up foundries and factories to manufacture all this. Soon there was a Confederate Army tannery turning out leather for harnesses, an ore and refining foundry for horse shoes…. To manage these affairs an Office of Army Supply was created that socialised all of these works. There were many objections, and law suits were spun, letters of complaint slowly found their way to President Davis’s desk in Richmond, and he would in turn chide Smith in a letter received eight months later. On the rare occasions when Smith received an explicit and direct order from Davis to cease an activity, he obeyed exactly.

In short order French armament corporations started swapping cannons for cotton along the Rio Grande. There was an increasing French military presence in México at the time and many French field officers found they had rifles, saddles, horses surplus to requirements which they swapped for cotton. The entrepreneurial spirt blossomed.

While England and France had limited sources of cotton in their empires, the mills of New England had ground to a halt for the want of cotton. Sure enough purchasing agents from New England were soon buying Trans-Mississippi cotton along the Méxican border. That is, they did not buy it but swapped it for Colt revolvers, ammunition, Remington rifles, steel knives, cassons, harnesses, heavy serge uniforms in grey which they brought with them from New England. That is right. In fact prior to the closure of New Orleans many of these … businessmen had been doing this since 1861, and they were merely relocating the trade in 1863 to the Rio Grande.

One result of this trade with New England was that the Confederate troops in the Trans-Mississippi were often armed with the latest weapons, just as the their Union counterparts received them, too. A shipment of 10,000 repeating rifles to New Orleans would be split, 5000 to stay and the other 5000 shipped on to México and Smith’s procurement bureau. Then when a Union cavalry patrol armed with Remingtons went out to blast Rebels, they quickly discovered the Rebels had the same rifles, and blasted back.

Since Napoléon the French had been leaders in artillery. The French sold cannons to Smith’s agents. Accordingly, Smith’s troops had better, though fewer, cannons than the Union forces they encountered. Better in that they were more accurate and easier to re-load.

To manage relations with México, France, Britain, and the New England traders Smith created his own State Department which negotiated agreements, exchanged agents, and so on. Everything was in writing. He made treaties with both Méxican and French authorities to pacify the border for this trade. Not only was he trading with foreign countries, he was trading with the enemy.

Nonetheless, his command often suffered privations because making or buying the material was one thing, distributing it over the vast reaches of the Trans-Mississippi with its few railways, many fordless rivers, its animal-track roads, disrupted raids by Federal cavalry was hard.

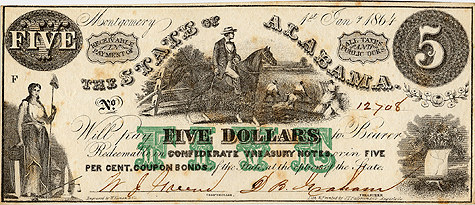

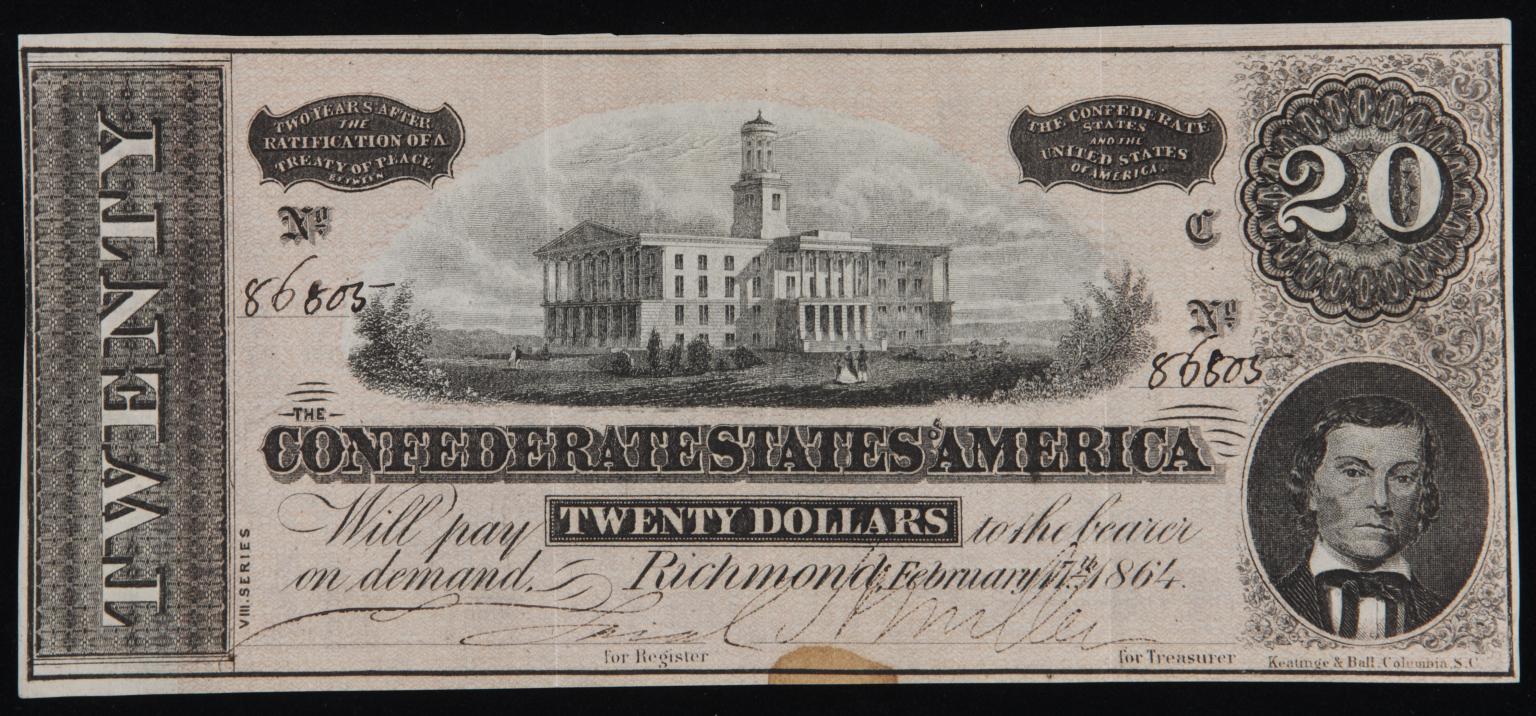

Cotton iconography features on nearly every Confederate bank note to remind the world of the white gold. On this five dollar note the overseer sits atop a horse with a whip in hand, ready to increase efficiency by using it on the blacks picking the cotton. All the while Lady Liberty on the lower left serenely observes. Most Confederate currency portrays blacks, too, always busy and happy at their work.

A good part of the book is taken up with accounts of military manoeuvres, battles, campaigns which make appalling reading. The size of the forces involved are microscopic compared to either the Virginia or Tennessee theatres but the death, the cold endured without shoes, the dying, the amputations, the disease, the swarms of stinging and biting insects, the gangrene, being constantly wet in the bayous, the malnutrition, the blinding heat, the field of rotting dead men are just as real.

The governors of each of the states and territories wanted Smith to defend every foot of their jurisdiction, the more so when the Union occupied most of a state. Missouri had to be defended, then recovered. Arkansas. Louisiana. Missions impossible, those. The Union picked and poked around looking for easy opportunities using the control of rivers to roam far and wide, supplemented by large bodies of cavalry riding on well-fed horses.

New Mexico and Arizona were the route to California gold and very early in 1861 Confederate expeditions went through Death Valley toward that El Dorado. Nature – it is called Death Valley for a reason – hostile Indians, and some Union army posts were enough to stop that. Even so there was a Confederate governor-in-exile and in the Confederate House of Representatives in Richmond sat a delegate from the Confederate Arizona Territory. Kansas figured as a continuation of the Jayhawk War and a refuge for raiders into Missouri, including the infamous William Quantrill (1837-1865), Jesse James (1847-1882), and other thugs later made into celluloid heroes. Slaughtering defenceless civilians was the preferred vocations of these men, e.g. Lawrence Kansas, not encounters with Union army patrols. There was also at least one raid into Colorado.

The Indian Territory (Oklahoma) was home to Cherokee Indians, regarded as the most civilised savages for they had adopted many of the white man’s ways: clothing, newspapers, slavery, and political representation. They negotiated an alliance with Kirby Smith against promises of future autonomy, i.e., no state of Oklahoma.

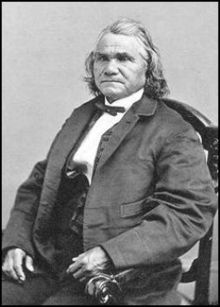

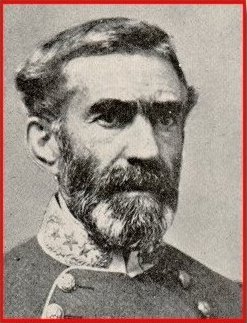

Apart from the shreds of papers affirming this alliance, it was embodied in a brigade of cavalry consisting of Cherokee and Creek Indians led by Brigadier General Stand Watie (1806-1871) himself a Cherokee, which remained loyal to the Confederate cause through thin, thinner, and thinnnest.

Stand Watie, Brigadier General C.S.A.

Stand Watie, Brigadier General C.S.A.

It operated independently, and mostly in today’s Oklahoma and disrupted Union communication and transportation, and occasionally joined one of Smith’s armies for a combined operation like the invasion of Missouri and then Arkansas. This brigade was one of the most reliable in Smith’s command.

While Texas was not often a scene of combat, when it was General John Magruder showed once again his tactical acumen and held off the threats made, including some French sabre rattling from México which Magruder saw-off in short order. In Arkansas General Richard Taylor did the bulk of the fighting in the Trans-Mississippi with the little wherewithal Smith could supply. He, too, had a tactical mastery that allowed him to overcome the odds often, but not always. On the debit side Generals Theophilus Holmes and Sterling Price made a mess of anything they turned their hands to, and Smith’s efforts to promote them to some harmless station, preferably in Cis-Mississippi, did not secure the support of President Davis, until it was too late.

By March 1865 a means of regular, albeit hazardous, communication had been established between Richmond and Smith at Shreveport. While the Confederacy was crumbling, the Confederate War Department launched an inquiry into the staffing Smith’s command. There were too many generals on the payroll! (Never mind that none of them, nor anyone else, had been paid in sixteen (16) months and then only in worthless Confederate dollars.) In an exchange of letters Smith was required to account for his every general and his duties in detail. Considering the vast distances within his command, he was not over-generaled, but try convincing the paymaster of that by letter.

So does the tail wag the dog.

Ever the dutiful soldier, he prepared the report but in the end he did not submit it. Why not? Because the War Department ceased to exist a fortnight later. Love it? The ship of the Confederacy is sinking, water is everywhere, and the head of payroll division sits grimly at his desk as the ship goes down demanding an explanation for those damn paper clips in the Trans-MIssissippi! It is the principle that is at stake!

As news of the surrender of Lee and then Johnston was broadcast in the Trans-Mississippi the scattered remnants of Smith’s garrisons, independent brigades, and armies evaporated. In some cases the local commander went to the Union line to surrender with some formality, but in most cases the Johnny Rebs walked away into the night. Smith surrendered formally at Galveston, and then took himself and his family off to México, because by that time, Lincoln had been murdered and the future was dark. He returned in late 1865.

He became a professor of botany and taught at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee for almost thirty years.

Conclusions? The author draws five conclusions from the study, and they make all the detail fall into place very nicely. However, I do wish they had been outlined at the start so I could have borne them in mind as I read.

1.The Confederacy conceived of the Mississippi River as a boundary, not a highway. Dividing commands at that boundary split forces that would have been better combined as the Federals proved repeatedly along the Father of Waters. This was the major strategic error. This decision divided command at the River, and then required explicit orders from Richmond for any cooperation across the River by Confederate forces on the two sides. More often than not, Richmond could not decide at such a distance what to do, and even if a decision was made, the communication was very poor. I trace this reasoning back to the general conception of military departments (matching state boundaries) which in turn paid court to states’ rights in the Confederacy.

2.Despite the hardships, the Trans-Mississippi Department sustained itself agriculturally and economically. It supplied the army with the necessities and civilian life went on. Though worn down and worn out it went on. The major problem was not production of the necessities of life, it was rather the distribution on the primitive roads, a problem compounded when the Mississippi River was closed.

3. Spared the extensive damage of general warfare experienced in Tennessee, Georgia, and Virginia, its armies never suffered a decisive defeat, yet the Trans-Mississippi did suffer a collapse of morale which was apparent in 1864, well before Lee’s surrender. That surrender was the the end of this collapse not the beginning. Kerby’s evidence for this collapse is ingenious.

4.Contrary to the conventional thesis that the ideology of states’ rights defeated the Confederacy from within, in the Trans-Mississippi General Smith worked effectively with the state governments in most ways, most of the time. Certainly, there was no Georgia in the Trans-MIssissippi, Georgia being the state that – some say – did more to defeat the Confederacy of which it was part then any other factor, except possibly South Carolina!

5.In the Trans-Mississippi the erosion of morale (see 3 above) that culminated with Lee’s surrender started very early in 1862. The initial cause was not defeat on the battlefield anywhere but the mobilisation of men and economy for war through conscription and impressment. Though everyone bore it, it sapped energy, enthusiasm, and spirit. Subsequent defeats sped the erosion but did not start it. Not sure what to make of this one. Again Kerby finds evidence, over looked by others, to sustain this thesis.

Robert Kerby

‘Alexander Stephens of Georgia’ (1988) by Thomas Schott.

When those who preferred compromise to war passed away, there remained those men of principle who preferred war to compromise.

Stephens had two brushes with the presidency. At one time the Little Giant of Illinois, Stephen Douglas, toyed with asking Stephens to be a vice-presidential running mate. Later the Secession Convention in Montgomery Alabama selected him to be Vice-President of the Confederate States. Indeed, he had even been mentioned as a president in the first days at Montgomery before Davis emerged as the preferred candidate.

Alexander Stephens (1812-1883), after a career in law, was a state legislator and member of the United States House of Representatives, where he was embroiled in the collapse of the Missouri Compromise, the Compromise of 1850, the Kansas Jayhawk War, the continuous crises that led to the Civil War.

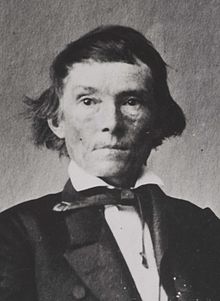

Stephens in 1855

Stephens in 1855

In his own mind Stephens was a pillar of virtue, a man of unblemished rectitude, absolutely consistent and forthright, unwavering, and never mistaken. He was also pivotal and influential in all matters he touched. That is his own opinion. He had no self-knowledge, it seems.

Schott shows in this well researched and nicely written book that Stephens was inconsistent, illogical, marginal, and often ignored. That Douglas briefly considered him as a running mate indicated how desperate Douglas was to hold together the Democrats as national party, spanning North and South, and how few Southern moderates there were that he might recruit. That he became Vice-President of the Confederate States is because more important players had contempt for this ‘empty compliment.’ Like most vice-presidents, Stephens found there was little for him to do.

Stephens was barely 5’ 2” tall and never weighed more than 100 pounds. He suffered ill health all of his days, and was often incapacitated for months at a time. He spoke in a shrill and high-pitched voice. Nor was he favoured by appearance. In today’s media he would never make it in politics.

He was a prodigious letter writer, and a finder of legal loopholes that made his legal career, an autodidact, who was as pompous as he was short. He had the intellectual vanity of a PhD.

When Jefferson Davis arrived in Montgomery to accept the presidency, he and Stephens met frequently. In those days, just as the assault of Fort Sumter occurred, Davis proposed a three-man commission North to negotiate a peaceful secession and asked Stephens to head it. Stephens declined because of ill health, he said at the time, and because, he added in hindsight years later, he saw no chance of success. Outliving many rivals, Stephens added much hindsight to his record; the the author does a good job of evaluating that hindsight against reality, seldom to Stephens’s credit.

While Davis and others argued that secession was a right to reconstitute a government, unconsciously aping John Locke, Stephens, ever in love with the sound of his own voice, delivered a paean on the divine justice of black slavery in his infamous Cornerstone Speech. That speech, widely reported and reprinted, lit a fire in the abolitionists of the North; even if Abraham Lincoln had been inclined to entertain the Davis peace commission that speech made it impossible. Stephens, the Vice-President of the Confederate States said that the purpose of secession was to defend slavery! He said further that it was a God-given right to enslave others. Moreover, that speech registered with the European powers Davis had been trying to convince to support the Confederate cause.

The author implies that Stephens’s speech was not intended to set a policy, but simply that when he started talking and mentioned slavery, the audience cheered, so he laid it on to milk more cheers from the audience. The author leaves little doubt that Stephens often talked without thinking. Before the death tolls mounted crowds North and South cheered all manner of claptrap. Don’t know what ‘claptrap’ is. Think Tea Party. Got it? Got it!

The Montgomery convention established a provisional government on the condition that the president be elected in one year. The critics of Jefferson Davis were legion. Some things never change and every newspaper editor in the South knew better than Davis how to conduct the government and wage a war, and said so often and in 30-point type. Even so, there were no other candidates; Davis (and with him Stephens) were re-elected unanimously. I cannot find out any more about this election from Wikipedia. There seems to have a popular vote of some kind and an electoral college vote.

What a utopia it would be if we were governed by the philosopher-journalists of the media who know everything.

He and Davis were much alike in their overweening egotism and thin skin, and when the government moved to Richmond, Davis no longer consulted Stephens. Accordingly, Stephens went home and spent most of the war in Georgia, and Georgia contributed as little to the war as possible.

Some historians say that Georgia made war on the Confederate government in the name of states’ rights. Georgia withheld men and material from the Richmond government on a significant scale. It stymied efforts to raise money with Georgia cotton and refused to cooperate with the Confederate Navy’s efforts to run the Union blockade, all in the name of states’ rights. Georgia Governor Joseph Brown won over Stephens with transparent and superficial flattery who then joined him in attacking his own government. Stephens could see no inconsistency in this behaviour. He never considered resigning, but continued to enjoy the status of being ‘Mr. Vice-President’ while disloyally opposing that government he formally served.

The Northern press fastened onto to this show of disunity with glee. European diplomats took note of this disunity, too.

The Confederate Constitution followed that of the United States very closely. It differed, however, in giving cabinet secretaries a seat of the House of Representatives where they would be subject to scrutiny. Schott accepts without examination Stephens’s claim to making this innovation, but the balance of evidence gives that honour to Judah Benjamin, the Attorney-General. (Benjamin had seen this practice in his travels to England.) In the event it seems not to have had any impact and it did not last since most cabinet secretaries stayed as far away from Jefferson Davis as possible by leaving Richmond.

Stephens on the Confederate $20 note which in 1964 would have bought a toothpick. The Confederate government printed about $1 billion dollars in notes, and most of the Southern states also issued their own script, then there were the bonds. In addition to inflation at the time, another result is that they have little value to collectors because there are so many of them. (Readers may remember that in the 1950s the judge in Carson McCullers’s ‘Clock without Hands’ had a stash of these notes which he proposed to put back into circulation to solve the economic problems of the day.)

Stephens on the Confederate $20 note which in 1964 would have bought a toothpick. The Confederate government printed about $1 billion dollars in notes, and most of the Southern states also issued their own script, then there were the bonds. In addition to inflation at the time, another result is that they have little value to collectors because there are so many of them. (Readers may remember that in the 1950s the judge in Carson McCullers’s ‘Clock without Hands’ had a stash of these notes which he proposed to put back into circulation to solve the economic problems of the day.)

Stephens never married and women are rarely mentioned in his extensive correspondence. He would say that he gave himself wholly to his country as a patriot. Did I say ‘pompous’?

While he fancied himself the only Christian gentlemen the country he did not attend church, though he read the Scriptures, and none of his opponents ever threw that in his face on the stump. Odd that. But he was not alone, e.g., Andrew Jackson.

Stephens’s political career started as a Whig, as did Abraham Lincoln’s. They sat together in the Whig caucus in Congress. As the Whig Party collapsed, unable to span the regional divides of North and South and of East and West, Lincoln became the second Republican presidential candidate, while Stephens sided for a time with Stephen Douglas as a Democrat. Class! Who was the first Republican nominee?

A pedant? His first election to the United States House of Representatives was as a member at large from Georgia, which had not yet been divided into Congressional distracts, because its western border was not surveyed. In his first speech in Washington D. C. he declared his own election invalid since the Constitution expressly required Congressional Representatives to be elected by districts of nearly equal size. He was satisfied with the startling effect on the few who heard it and did not act on his own contention, say, by resigning. By the way, the districts were surveyed and in two years he was re-elected from a district.

At the end of the Civil War Stephens was arrested and jailed for four months, the first two were pretty hard but the last two were lax. After his release he was a United States Senators-elect from Georgia but since he had not taken the loyalty oath, he was not allowed to take his seat. Later, after taking the oath, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives for ten (10) years where he served without distinction, and then briefly – less than a year – governor of Georgia.

In this post-bellum years Stephens proved (to his own satisfaction) that he had never erred, that he had opposed slavery, that he upheld the United States Constitution, that he had the right war policy, and more. His capacity for self-delusion had no bounds. That old adage about a person being promoted one level about the level of competence came to mind in his case. In the confusion of wartime, his promotion was several levels above his competence.

The book is meticulously researched and written with a light hand. It gives credit where credit is due to Stephens, e.g., he did visit wounded soldiers in Richmond hospitals now and again, something that Jefferson Davis could never bring himself to do because he thought it was inconsistent with the dignity of his office. After all, one of those hill-billy soldiers might not address him as ‘Your Excellency’, which the only form of address he found suitable for his high station! The book also points out Stephens’s volatility, repeated mistakes, lies, and more.

My one complaint though is that the there is no terminal chapter with a final, overview assessment of Stephens after readers have forced-marched through 520 pages of detail. A bigger picture at the end might give that details some added meaning. Without that picture a lot of that details seems, well, detail for the sake of detail.

A ticket of Douglas and Stephens would have give the wits something to talk about, for example, the Leprechaun ticket or the garden gnome slate at 5’ 6” and 5’ 2” respectively.

De Gaulle: The Ruler 1945-1970 (1985) by Jean Lacouture.

The story goes on, and gets even stranger. Although de Gaulle was wildly popular in France at the Liberation, the restoration of political parties, particularly the Communist Party which was taking orders from Moscow, made political life unpalatable to de Gaulle. This Fourth Republic from 1945 to 1958 was a replay of the Third Republic, divided, carping, jealous, each undermining the other for momentary advantage, negative, inward looking, oops starting to sound like Canberra. All this began while the Germans still occupied ten percent of the country. The parliamentarians had forgotten nothing and learned nothing.

Colonel Trinquier, one the leaders

General Massu and his paratroops, a pivotal actor

General Massu and his paratroops, a pivotal actor

Many of these ’wolves in the city’ (a reference to Paul Henissart’s book of that name) knew de Gaulle personally but they did not seem to know him at all. He had been on record since 1943 for self-determination in Algeria, yet they thought he would re-impose French domination there. By the way, there is plenty of evidence that a coup d’état was likely. Two regiments of paratroopers from Algeria were emplaned for Paris, and another regiment deemed loyal to the plotters was assembled in the Bois de Boulonge on the designated day. Tense!

Historians make careers in speculating about de Gaulle’s role in this plot. Lacouture concludes that he knew something as drastic as this was in the offing, and probably thought it would take such a dire threat to bring parliament to its senses, so he remained mute, allowing the plotters to think he was with them. That rare quality in a politician is the ability to keep quiet and say nothing, and de Gaulle had that.

The call was made and de Gaulle was sworn in as prime minister, that cooled the plotters who relented, standing down the paratroopers in Algeria, though there is an amusing story that two police officer riding bicycles through the pre-dawn Bois coming upon a regiment of a thousand fully armed paratroopers very early in the morning and ordering them to disperse, which they, lacking any further orders, did! Now that is civilian authority.

De Gaulle proposed the Constitution for the Fifth Republic which gave a president great powers and took that office by an indirect election. An indirect election? Political Science students know what that means but most punters do not. It means, in this case, that 80,000 office holders (municipal councillors, mayors, parliamentarians, and members of the judiciary were the electorate in this first presidential election under the Fifth Republic. They gave de Gaulle a two-thirds majority against a field of six other candidates, including the inevitable Communist. In the subsequent parliamentary elections it was another two-thirds for the supporters of de Gaulle, though by this time there were two Gaullist parties. The Communist Party nearly disappeared in this election, going from 120 seats to 10. Such indirect elections were the norm in the 19th Century well into the 20th Century.

De Gaulle remained faithful to his belief that circumstances determine all, and on Algeria he stalled, delayed, spoke in enigmatic phrases, while wooing first Algerian nationalists and then moderate generals in his own army, now and again offering a dissident general a plum appointment abroad as ambassador, promising others new commands if only the crisis could be resolved, coaxed parliament to defer to him, and took his time. During all of this he came to realize himself that there was no alternative but complete independence, though he had long preferred a more gradual option that retained a filial link, and finally he said so.

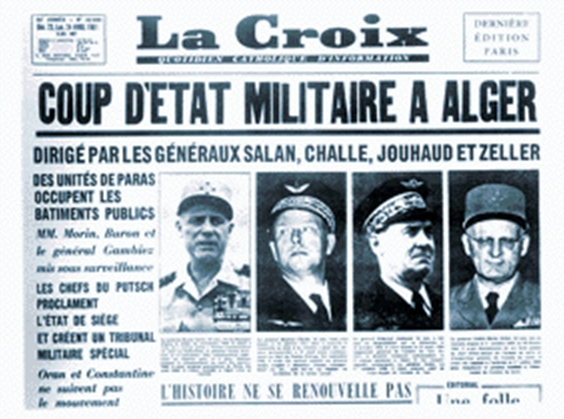

Then there was a coup d’êtat attempt, but by this time the plotters were too weak, too divided, the government too strong, the Algerian nationalists too disciplined, and having anticipated this, de Gaulle out manoeuvred them.

That led a fruitless and bloody civil war between the Organisation de l’Armée Secrète (OAS) – the ultras – and France, which was just as merciless and bloody as the repression in Algeria had been. None of this story is pleasant, but in the end a worse result, which was very likely at several stages, was averted and de Gaulle, love him or hate, must be credited with that. No one else could have done it.

Nor was any of it easy. Men who had been close to him for years turned against him. Others tried to kill him, several times; nothing he did satisfied the liberals, the nationalists, the Communists, the pied noirs of Algeria…. When he stalled and delayed lives were lost. It was a terrible time, and the OAS brought the war to Paris by bombing cafés. Yes, long before the IRA got around to blowing up customers drinking coffee, the OAS did it in Paris. It was all deadly serious. At the height of this struggle de Gaulle was seventy (70) years old. Reader what will you be doing at 70?

In 1965 he contested his only popular election and won 55% of the vote in the now familiar two-step process. He defeated François Mitterand.

Having learned how unreliable allies were in World War II, President de Gaulle hewed an independent line in foreign and defence policy. When England tried to prevent a European Union, De Gaulle committed himself to it as a third force between the Anglos and the Communists. Later when the United Kingdom wanted to join the European Union…. Likewise he wanted France to be a force to be reckoned with from now on, and that meant nuclear weapons, and developing these weapons could only be done outside NATO, so France left NATO.

Originally he wanted to occupy the east bank of Rhine, exact reparations from Germany, monopolise the coal from the Saar, and dismember Germany, if not quite as ruthlessly as Clemenceau proposed in 1918, but de Gaulle changed his mind. He originally wanted to manage the movement to independence of colonies, but he changed his mind. He originally opposed a European Union, but he changed his mind.

Instead of reducing Germany, de Gaulle led the way in bilateral relations with West Germany. In one remarkable instance he gave a speech in German at a factory in the Ruhr in which he challenged his auditors to do something very hard, very unlikely, never been done before, virtually impossible…to live together in peace! I did once find it on a web site but I have since lost the address.

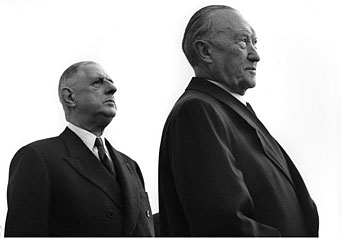

de Gaulle with Konrad Adenhauer

de Gaulle with Konrad Adenhauer

It is a common mistake that I have read in that self-important organ of opinion the Sydney Morning Herald more than once and heard on the ABC pulpit more than once that the demonstrations of May 1968 drove de Gaulle from office. In fact he left office in 1969, as always in his own time and in his own way. But what is a year to a journalist? Just another annoying fact, or so I was told by a Fairfax journalist when I pointed out this mistake.

In fact in the elections de Gaulle called after those demonstrations in June 1968 returned 352 Gaullist out of 487 seats in parliament. A resounding victory! In fact he resigned in April 1969, when he was seventy-nine (79), after the defeat of a referendum he sponsored on the reform of local government. He was ready to leave and the referendum was a convenient trigger. He died within a year.

A few loose ends. De Gaulle assigned the earnings from his memoirs and other books to the Anne de Gaulle Foundation that he and Yvonne started. The Foundation supported mongoloid children and their parents. The pygmies of the press give this gesture no publicity.

While head of the provisional government, prime minister, and president de Gaulle paid his own way. That is he charged almost nothing to the state. He paid for his own telephone calls. He had meters installed in the living quarters so he paid for the heat, water, and light there. Paid for his own postage stamps. We know this from biographers. He lived on his pension as a colonel; his promotion to general had not been confirmed by the Reynaud government during its flight and so was never technically consummated leaving him entitled to a colonel’s pension which he accepted without demure. Nothing was said about it at the time. I am not sure what conclusion to draw from his frugality except, as always, that he did things his way.

In the preface to this translation the author complains that the publisher abridged volumes two and three into a single tome. The original French three volumes were squeezed into two by combing the last two in one with much editing. It is not clear who did the editing. Was it the translator or the author himself? What I can say is that I found the blow-by-blow account of the political machinations from 1946 to 1969 is far more than I could digest in even this abridged form. What that detail does do is show how hard the work of politics is.

What I missed, and I do not know if it is there in the original, is detail of de Gaulle’s years in the wilderness. After all it was twelve years. He gave some speeches in the early years and he wrote his memoirs, yes, but what else? Did he reassemble his family? Did he go to his grandchildren’s christenings? Did he read a biography of Jean d’Arc? She by the way seems to me to be his alter ego. Whereas she heard God, he heard France.

Since his passing many politicians, parliamentarians, parties, and movements in France have said they are Gaullist. What does that mean, ‘Gaullism’? First, it means an independent foreign policy and that implies having the means to be independent. Second, it means planning and co-ordination in domestic policy. In economics it means Keynesianism. Finally, it means the expansion and defence of French language and culture along with social conservatism. In short, big government, big enough to please Gough Whitlam.

There is a plaque on the wall of a building in London at Carlton Gardens noting that De Gaule had an office there during the war. Virtually every word on this plaque is contentious. To Vichy he was not a general; his commission lapsed when he refused the order to surrender. When he set up an office in Carlton Gardens he was alone. The Committee came much later and by then de Gaulle’s headquarters had moved. Likewise, that well known term ‘Free French’ renders ‘France Libre’ which is much broader – Free France, not just some Frenchmen but the whole. Moreover, in 1943 when the Anglos were trying to displace de Gaulle they started using the term ‘Fighting French’ to undermine him. In 1940 there were no ‘forces’ with de Gaulle.

I long wondered about the 140,000 French troops evacuated from Dunkirk in May. Should de Gaulle have recruited them. He could not because they were transhipped from Dover to Bristol by train in a great hurry and shipped back to Bordeaux arriving just before the capitulation. At the time the ambition was to get them back into the war, since no one in England, least of all the French generals with the troops, anticipated a capitulation in June. It was Churchill who ordered the British to evacuate soldiers from Dunkirk without regard to uniform. Until he intervened the evacuation was limited to Brits. Thereafter, the evacuation included Brits, French, Belgians, and even some Poles who with the French.

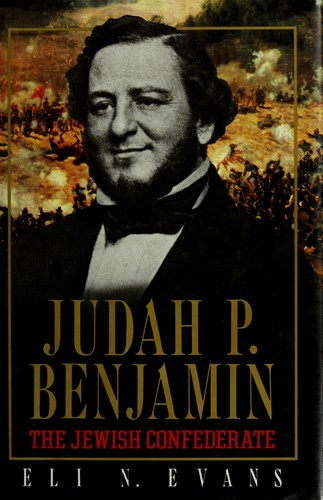

Judah Benjamin: the Jewish Confederate (1988) by Eli Evans

Reading about Jefferson Davis earlier reminded me of his alter ego in the Confederate cabinet, Judah Benjamin, and then a correspondent told me that one of Benjamin’s textbooks from his post war career in the 1880s is still on law school curricula, a fact that I verified easily. In an idle moment – half-time in a Niners game – I looked for a biography and this is the one I found. Published by Free Press, I took that as a mark of quality and acquired it. It is an excellent study with some surprises in it.

What made Benjamin notable in the lackluster Richmond government was first and foremost that he lasted the course of the war and no else did, apart from President Davis himself. As I discovered from reading Allan Tate’s biography of the irascible Davis, Benjamin was one of the very few who somehow got along with that moody, dyspeptic, volatile, and intemperate man. Evans suggests that Benjamin tried all his life to fit in without assimilating or converting to Christianity, though his Judaism was nominal.

Here then was a man who made a lasting contribution to legal knowledge, held very important national executive positions in cabinet for four years, and alone managed to work closely with his president. All in all a singular set of credentials.

Note, the only other person who managed to get along smoothly with Davis was Robert E. Lee, but they seldom met face-to-face, whereas Benjamin saw Davis virtually every day, and of course Lee had his military achievements as a buffer.

First, Benjamin’s background. His family were Sephardic Jews who originated in Portugal and then fled the Inquisition to England. His parents migrated to Charleston in South Carolina (which I visited last year) where Judah was born and grew up. Charleston was a major seaport then and had a sizable Jewish community. His parents were not devout and neither was he, but no one ever let him forget that he was Jewish. It was often thrown in his face, and, if not, then muttered behind his back throughout his life.

Like so many others, when he was of age, he went west, to New Orleans (NOLA) in the 1820s.

Louisiana had only just become a state. He apprenticed in law and made ends met by tutoring in English while himself learning Creole French. Then as always he had a prodigious appetite for work, and brought to it an organized and systematic mind. He made a tidy sum in NOLA by compiling a guide to the Code Napoléon that formed the basis of the Louisiana law.

It is a complex framework that he distilled, valuable to any law office, but the more so for other English speakers moving to Louisiana and encountering the Code for the first time. In this he demonstrated his eye for the niche where he could do well by doing good à la Ben Franklin.

He married a Creole woman who led him a merry chase for years before and during their marriage. Vexed as that was, it was thanks to her that he travelled to England and France, as well as Spain and Italy. For most of their marriage, she lived in Paris which he visited one month a year. To finance these trips he undertook commercial work in England and France that gave him knowledge and contacts that were an asset later.

In the 1840s the American political party system was fracturing as the old compromises wore thin and the great compromisers (Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, John Calhoun, who preferred compromise to war) passed from the scene and firebrand intractables who preferred war to compromise came to the fore in the North and the South. His legal accomplishments recommended him to NOLA Whigs who got him elected to the state assembly. His appetite for work (and lack of the distractions of a home life) made him their candidate for a Senate seat in Washington D.C. which he won. He lived for a while in Decatur House which stands today. As the Whigs dissolved he changed allegiance to the Democrats.

To step back, just before he ran for the Senate, in the last days of the Millard Fillmore Administration, President Fillmore had to appoint a Southern to the Supreme Court (regional balance then as now was honored) and he offered it to Benjamin. He declined. It was almost hundred more years before a Jew was appointed to the Supreme Court. Class, can you say who that was? Yes, that is right Woodrow Wilson had his beau geste and appointed Louis Brandeis of the Brandeis Brief who was not only a Jew but an innovator!

In the United States Senate Benjamin defended states’ rights but not directly slavery. He became a slave holder when he married and set up house in Louisiana with his errant wife, but had not grown up in a slave holding family. His legal mind, command of precedents, great memory for the dumb things others said, these combined with an assured posture and deep voice earned him a reputation as an orator in the well of the Senate. The important point is that he was a moderate, not a Fire Eater who proclaimed slavery or death like Henry Foote or Thomas Yancey.

When secession started and Davis composed his first cabinet he wanted a geographic spread and he knew Benjamin from the Senate. He offered Benjamin the post of Attorney-General, which he took. At the time it was supposed there was hardly any need for an Attorney-General so his appointment was accepted though his Judaism drew comment in the newspaper.

Benjamin on the Confederate $2 note as Attorney-General.

Benjamin on the Confederate $2 note as Attorney-General.

In the first cabinet meeting in February 1961 he made the only strategic suggestion that comatose body ever conceived. He proposed that the Confederate States government acquire (by purchase or requisition) a million bales of cotton and immediately transport them to England and warehouse them there as surety against future purchases of arms and ships. The proposition died on this lips. What did this short, rotund, Jew who had never served in the army know of war. It would be over the three months. Davis dismissed the proposal in very few words and patted Benjamin on the arm in a typically patronizing way.

That incident aside, Benjamin who had long studied those around him in court to assess the best tactics to use studied Davis, and found ways to make himself indispensable to the cantankerous and thin-skinned Davis.

Whereas the others members of cabinet put as much distance between themselves and Davis as possible, Benjamin took an office next door and socially paid court to Mrs. Varina Davis. He sent her theatre tickets, offered to do things for her children and so on. She soon offered him another point of access to Davis. In the office Benjamin became something like a chief-of-staff who handled the routine, acted as a gatekeeper for those who wanted to see the President, and drafted everything that needed to be written. In a few weeks Davis could not do without him.

When the victory at Manassas was not exploited the incumbent Secretary of War in the Confederate cabinet resigned in a huff and retired to Florida. Since Davis fancied himself a master strategist what he wanted in the War Department, such as it was, was an instrument who would do his bidding. Who better than Benjamin for whom no job was too small or too big. In June 1861 he was appointed Secretary of War, he of no military experience whatever, who had never fired a gun. He did not hunt, duel or any of those like manly arts so common among Southern gentlemen. However, he was a hard working administrator with an eye for detail and a willingness to work with others, qualities rare in Richmond.

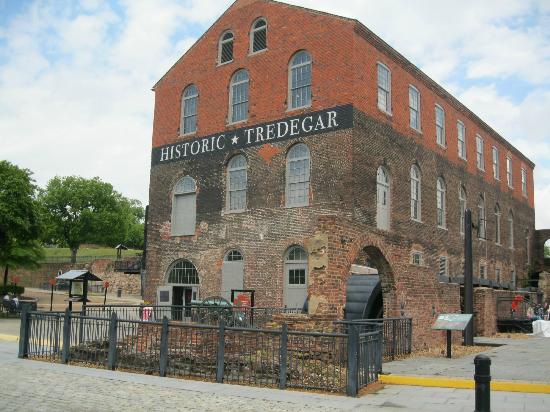

By the way, Evans argues that Richmond would have been the primary target of the war with or without the Confederate government in residence because it possessed the only ironworks sufficient to forge heavy weapons, cannons and shells, in the Tredegar Iron Works.

The Tredegar Works today.

The Tredegar Works today.

In fact, he argues the decision to move the government there had the effect, and perhaps that was the intention, of shielding these iron works with a great army. A point I had never before heard.

The Union anaconda strategy worked and NOLA fell early in the war cutting Benjamin off from his sisters there and his considerable property was confiscated by the Union army. He now was completely isolated in that sense, and Evans suggests that drove him to work even harder for Davis. If Benjamin lost office he could not retire to his home as others who left cabinet had done. His future, if future he had, was now in Richmond.

The winds of war blew more defeats and Benjamin was blamed for them. Evans produces a fascinating correspondence in one instance. Benjamin tells Davis he did not re-supply the Army of Northern Virginia after Antietam because there were no supplies left, no shot, no shell, no horses, no mules, no cannons, no rockets, no men in reserve, no corn, no feed, no salt pork, no nothing and not a gold dollar to buy it. But rather than admit that and (1) undermine civilian and military morale and (2) discourage potential European allies and investors that he would take the blame. Davis agreed to let him be the scapegoat in the newspapers and gossip, which went ballistic in the blame game. Watch the ABC news tonight for an example.

Yet Davis quickly moved to promote him to Secretary of State in late 1862, a post he held to the end in May 1865. Of course the pundits were outraged, Benjamin the Jewish fiend who had no doubt profited from stealing army supplies was rewarded for his perfidy with promotion! That from the Richmond press. But the Confederate Senate approved the appointment because its members knew how indispensable Benjamin was to Davis, even if they did not know about the lack of supplies.

Now Benjamin had a job for his talents. He spoke French and had done commercial law work in England and in France in his travels to his wife who was a favorite at the court of Louis Napoléon. He had many legal and social contacts in both countries. Davis and many others Southerns hoped that England and France would intervene in the war in some way. There is no doubt that it was a tempting proposition. To England it offered the chance to emasculate a commercial rival in New England and perhaps reclaim territory lost in the Revolutionary War. To France it offered the prospect of a Confederate ally to realise Louis Napoléon ambition of colonizing Mexico.

What Benjamin quickly realized that rather than risk a confrontation with the United States, what suited both England and France was to see the Americans in a deadlock. That would serve the purposes of both. England could trade and France could enter Mexico with no reaction from El Norte.

Benjamin went on the offensive. He arranged for Confederate sympathisers to go on public relations tours in both England and France. He paid unscrupulous journalists in those countries to write favorable articles and so on. He directed Confederate ambassadors in each country to offer inducement (bribes) to officials to draw their countries into the conflict.

Given the Union’s naval blockade, making these arrangement was difficult but he found paths through Mexico and Canada, though a letter might take three months to get from Richmond to Paris or London. And many letters did not make it. As a precaution against interception many of his official dispatches were coded and disguised as personal letters from a woman in Canada to a cousin in France, or a businessman in Mexico to a bank in England. In addition, he funded agents in Canada to foment trouble on the border with the United States. He also tried to organize support, financial and recruits, for the Peace and anti-conscription movements in the North, the Copperheads. One example in Vermont features in Howard Mosher’s delightful novel ‘On Kingdom Mountain’ (2008).

In short, he tried everything.

These confections, however ingenious, could not outweigh the realities of blood and iron. The Europeans would let the battlefield decide the matter.

As the military situation produced shortages. the scapegoating of all Jews, but particularly the most visible one, increased in the South. Jews were accused of hoarding commodities, when in reality they had nothing either, he least of all. When a French banker made his way through Mexico to Richmond to negotiate for cotton, he and Benjamin spoke French. Though the resulting contract was very favorable to the Southern cotton interests, it was not enough! The press, the Congress, the know-it-alls, society ladies, men in the ranks all denounced Benjamin for selling out the Confederacy in some invisible way. Why else would a Jew speak French to a monolingual Frenchman but to conspire?

This reasoning is not more stupid than we hear today from many quarters. Nothing is ever enough. The only explanation of a shortfall is personal malfeasance. Sounds like Pox News! Simple minded and loud. Or is that the ABC these days?

The more Benjamin was pilloried, the more he took the only refuge he had, namely Richmond’s small Jewish community. But seen in the company of other Jews only intensified the hostility that good Christians directed at him.