I wanted to read this little book (unpaginated) because my efforts—thrice over the years—to read Auguste Comte’s (1798–1857) ‘Système de politique positive’ (six volumes, 1851-1854) failed. While Comte was the centre of much intellectual ferment he has not attracted much attention so I have not come across another exposition. I also thought Mill a good expositor, most of the time.

Comte was private secretary to Henri de Saint-Simon, that father of French utopian socialism, in the tag that Karl Marx hung on him never to be shed, who was himself a relative of the diarist Le Duc de St.-Simon of the Sun King’s Court. Moreover, any history of sociology will accord Comte pride of place alongside such giants as George Simmel and Émile Durkheim. George Eliot, the novelist, mentions him in some of her novels in a very favourable way. His name comes up now and again. When I was in Montpelier for a conference I saw a plaque on a school where he was educated. Time to scratch this itch, if only a little.

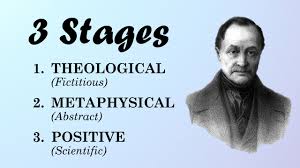

The ‘Système de politique positive’ offered a philosophy of history that explains humanity’s social evolution through the stages of theological and metaphysical, culminating in the age dawning in 1851, the age of Positivism. These stages take different forms in mathematics, science, the arts, industry and so on, and Comte described them in great detail.

Auguste Comte with the three stages of social evolution.

Auguste Comte with the three stages of social evolution.

In this context ‘positivism’ means a lot more than positive. It means saying only what is demonstrable. He is a materialist after Karl Marx’s own heart. Facts shape ideas, and not vice versa. One of many consequences of this foundation is that reason serves feeling but does not govern it. Herbert Spencer took much of this epistemology on board, and, like it or not, set it forth much more succinctly and clearly than did Comte.

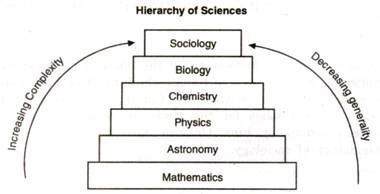

In Comte’s interpretation mathematics is THE science, the foundation of all else, because it is the simplest and sociology is the last science because it is the most complicated. The Wikipedia entry has a potted account that shows signs of the editorial wars for which it is infamous.

Social evolution, per Comte, thanks to Positivism, will lead to a unanimity on all matters, starting with mathematics, by sticking only to the demonstrable. The result is utopia, though Comte does not use the word. Once this unanimity is achieved, then a corporation of philosophers, regarded with reverence, but excluded from political power or material riches, with a modest support from the state, will direct the on-going education (and life) of each individual and the society as a whole. While they have no authority, a sanction from this college of philosopher has a crushing social and moral force. They superintend both the public life and the private life of each and all. They are a panel of very Big Brothers.

Comte’s hierarchy of the sciences.

Comte’s hierarchy of the sciences.

There co-exists a temporal government which is comprised of an aristocracy of capitalists, led by bankers, seconded by merchants, then manufacturers, and finally agriculturalists. In each case the noun refers to the owners not the workers in these domains. There is nary a word about a role or voice for the multitude who do not own banks, grands magazines, factories, or farms. However, there is completely free discussion. The elephantine six volumes brings forth this rather simple-minded pastiche on Plato’s philosopher-kings. Absent is any mentioned of women, contra Plato. By the way, St. Simon was a banker.

Comte could see no reason why inferiors should elect the superiors who will rule them. Public officials should be responsible for training and selecting their own successors subject only to the approbation of their own superiors. This is a man who believed in hierarchies. A citizen must have a settled career by thirty-five, and after that may not change. This is a man who believed in order at any price. No one may pursue occupations that are not useful. So much for basic research. He was specific about stopping useless research into magnetism, archeology, astronomy, and more. Imagine how popular he would be today with budget cutters. The corporation of philosophers will decide what is useful. End. This corporation will also decide which one hundred, yes, one hundred books will survive and the rest will be burned! One hundred is enough, the rest mere distractions.

Comte regarded rich capitalists as a public functionaries and stipulated that they must act accordingly. Talk about a dreamer. What socialists would achieve by law, Comte hoped to achieve by education and suasion, capped with the peer pressure of public opinion.

Such a result may cause a reader to doubt that it is worth the effort to study the volumes that lead to it in order to understand how Comte arrived at such banalities. So says Mill in one of his drôle asides.

The second half of this unpaginated book is another essay on Comte’s later works which were just as ponderous. Comte took the time to explain his own genius. He never read anything but reflected within himself. Echo Rousseau. The result is an autodidact with a great conviction. He was mentally unstable as a youth, voluntarily spending time in an asylum, and later attempting suicide. In middle age, like Mill, he found the love of his life and told the world. This comparison to Mill’s austere passion for Harriet Taylor might have warmed Mill to Comte.

In the latter works Comte goes even further, devising a social religion that leaves behind the metaphysical and theological claptrap of organised religion and preaches this doctrine and this doctrine alone: live for others. In arriving at this creed, he coined the word ‘altruism.’

‘Live for others’ is literal. One should only do what benefits others. This is not Jesus’s admonition to love neighbours as oneself, but rather not to love oneself at all but only to love neighbours.

Comte was systematic as indicated by the title of the work cited above, and he carried this creed through in everything, from diet (eat only enough to be able to serve others), to dress (simple and utilitarian to serve others), and so on. Everything becomes a moral question settled by this one doctrine. In short, he required that each of us live as a saint practicing self-abnegation in our every act. Followers? He had none. Nor is there any reason to belief he lived as he advocated, rather like most pundits today, he preferred preaching to practicing.

His lady-love died within a year of their conjunction, consequently Comte, like others so bereaved, was attracted to spiritualism. He included guardian angels in his civil religion, and it seemed to be more than a metaphor.

He also proposed an elaborate civil religion with a Pontiff Positive, which would preach the doctrines he proposed. He supported Napoleon III’s coup d’état because it did away with the charade of elective democracy (which Comte always dismissed as the English disease), and predicted that in a few years Napoleon would turn over government to three wise men. Guess who would be the first to be chosen. That day came and went without the magi.

Comte was not a man who knew when to quit. He proposed to give each day of the year a name, to make the week ten-days along, to rename the planets, to change spelling and orthography, spending pages and pages on the evils of diphthongs. (Look it up!)

The more one reads of Aristotle, the more clear is his towering genius. Ditto many others. In the case of Comte, the more one reads, the less one wants to read any more.

Recently I saw on Télévision Française 2’s news broadcast aired by SBS each morning, which I watch for my daily French lesson, the induction of a scholar into the immortals of the Collège de France, the robes, the ritual procession, the pecking order, the props were all very Masonic to this vulgarian. (There were no more than three women; the immortals number one hundred and no one may resign, ergo someone has to die for a new member to be selected.) These individuals are the sort Comte had in mind for rule.

Collège de France logo. I could not find any imagines of a ceremony such as I saw on the news.

Collège de France logo. I could not find any imagines of a ceremony such as I saw on the news.

Of course, while they retain the trappings of veneration, in fact the broadcast had the air of curiosity more than reverence.

This book is not Mill at his best as an exposition. But it soothed my it itch for Comte. Each sentence is a thicket of dependent clauses, noun phases so long that a GPS is needed to find the predicate, encyclopaedic asides, orphaned relative pronouns, that it taxed this reader. In the essays, for which he was paid by the word, Mill is prolix; in his books which he paid for publishing by the word, he is terse. Go figure. His father had Scots ancestry.

Skip to content