Genre: fiction, biography

GoodReads meta-data is, in the order listed above, 496, 452, and 544 pages, totalling 1,492 pages, the trilogy as a whole is rated 4.6 by 308 litizens. Each of the separate titles has an entry on GoodReads, as well, with a separate rating for detail hunters.

Verdict: Robert Harris is a genius at such historical fiction.

‘What nation has ever erected a statue to a man because he was rich?’ Sorry Clive Palmer but there it is.

‘A home without books is a body without a soul.’

For reasons only known to the high priests of publishing, the separate novels have different titles in the USA and UK editions to confuse librarians, readers, and buyers. Beware.

The three titles of this trilogy offer the reader an eye witness to the long fallout of the Roman Republic as experienced by Tiro, slave to Cicero. The author’s premise is that long after the events, Tiro wrote down what he saw and heard, making use of the extensive notes he had taken along the way, as well as his prodigious memory. The result is a biography of Cicero in all but name. Well, I read it that way.

Tiro was Cicero’s confidential secretary and they were seldom apart in waking hours for forty years. Cicero had a mania for detail and wherever he went, Tiro was there to take notes of everything said by Cicero and others. These notes were possible because Tiro had devised a shorthand notation that allowed him to keep pace with even the most garrulous speakers. Tiro is credited with the ampersand ‘&’, the abbreviations etc, NB, i.e., e.g., and much more. Xenophon had some primitive version of shorthand nearly four centuries earlier but none of it survives. He used it for notes on his campaigns.

Tiro’s written records were a novelty and it often gave Cicero an edge against his numerous opponents, rivals, and fellow travellers. Tiro’s perspective allows the author some distance from the subject, while making clear Cicero’s towering achievements, his errors, foibles, and lapses are there to see.

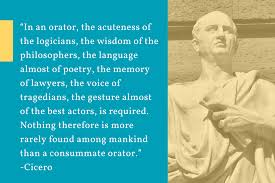

Cicero was a wordsmith and much of the novel takes the form of dialogue and even speeches, yet it is so well judged that it does not seem wordy, nor does the pace slow, despite the verbiage.

Other intellectuals like Thomas More, Niccòlo Machiavelli, Alexis de Tocqueville, John Stuart Mill, and Max Weber, all had political careers, but none of theirs was anything like Cicero’s. A country bumpkin, he rose steadily with ambition and ability in the Roman Republic. HIs rise is the more remarkable for his disinterest in the sword and his lack of money, normally the keys to success. What he had in plenty was words with which he often found a high ground unseen by others quick to the sword or awash in money.

His legions were his words, and by them he rose and survived, often against the odds, and occasionally cut down his enemies. If he finally lost to the sword at sixty-two he mused that having lost the past and the present, his words might still win the future: the judgement of history. In that he was right. We know him, his words, and his fame but those of few of his many enemies.

He also became a household name then and now, sort of. Great oratory, like great poetry or music, is a distillation of emotion into an exact form. But to convince other he himself had to be convinced, and part of the story here is how he convinced himself of this course or action and that, sometimes in contradiction to one to the other.

He was neither a demagogue nor a patrician, but at times allied with each. At times one faction used him and at other times he used that faction. He steered toward the best interest of Roman, and that chiefly was stability without civil war and with civic freedom. His incessant search for a compromise brings to mind another orator, Henry Clay. In his flexility in trimming to steer to the distant shore of peace he likewise brings to mind another Kentuckian, Abraham Lincoln. Cicero had few principles but he had a goal that determined his method.

Seeking stability meant making strange bedfellows, and changing them from time to time. Patronage, when he had it, was used to divide and confuse enemies, not to reward friends, and later that tactic cost him friends.

He lacked the consistency so loved by the simple-minded of journalism. The straight line is seldom the shortest way between the here-and-now and peace in the world of politics.

He revelled in the political world: ‘Politics is history on the wing! What other sphere of human activity calls forth all that is most noble in men’s souls, and all that is most base?’ Hmm, well most major sports now fit that bill but….

The best analogy for statesmanship in Cicero’s opinion is ‘navigation – now you use the oars and now you sail, now you run before a wind and now you tack into it, now you catch a tide and now you ride it out. ‘Just as the purpose of a pilot is to ensure a smooth passage for his ship, and of a doctor to make his patient healthy, so the statesman’s objective must be the happiness of his country. One merely adapts to circumstances as they arise.’ Navigating politics takes years of skill and study, not some manual written by a deep thinker.

Into the mix of the Roman Republic came a lightning bolt named Julies Caesar wearing the mask of a wastrel while scheming for an even bigger prize than Cicero ever imagined. And the rest is history….

Cicero succeeded beyond his wildest dreams but his cursus honorum to success left many discarded allies, out-distanced rivals, and bred in the bone enemies, and with success Cicero changed, became complacent, over confident, and even, surprisingly for this restless man, lazy. Meanwhile, his enemies accumulated. In semi-retirement he was no longer a player but he was a symbol that those enemies, some of them patricians and others plebeians, could use to arouse followers, the discarded allies and the beaten rivals.

Then the final rupture came and he came back into a no-win situation where this wily old fox was outwitted by a gangling teenager called Octavian.

Among the vast cast of characters there is the anti-Cicero, namely Cato, who lived like a pauper, despite his great wealth, and embodied his uncompromising Stoic philosophy. When he learned that Caesar would arrive the next day he did as he advised others to do: he bathed, dined, read philosophy, and then fell on his sword to commit suicide. N.B. Cato did not bathe often and seldom ate more a few olives.

The history is well known and Harris takes some liberties with it to make a coherent story seen from Tiro’s point of view by occasionally back-filling. In lesser hands these occasions would have seemed intrusive and didactic but not so here. There is also some fiction in this work of fiction.

A patient reader finds many rewards in the descriptions of the time and place, and in Cicero’s insights into the world of Roman politics. Here is a sample of Cicero’s perspective on Roman democracy, such as it was. ‘You can always spot a fool, for he is the man who will tell you he knows who is going to win an election — an election is a living thing – you might almost say, the most vigorously alive thing there is – with thousands upon thousands of brains and limbs and eyes and thoughts and desires, and it will wriggle and turn and run off in directions no one ever predicted.’ And that living zoological aspect of elections is what Cicero found so fascinating. He added that elections in the end were ’perhaps one of the things that killed the republic: it gorged itself to death on votes.’

Or consider his remarks on history: ‘To be ignorant of what occurred before you were born is to remain always a child. For what is the worth of human life, unless it is woven into the life of our ancestors by the records of history?’

Those readers who know these Romans and these times through Shakespeare and the many derivations from the Bard, will find a harder and darker reality in these pages. Shakespeare, too, took liberties for his purposes, because he was not writing history. That is fine, the problem is some naive readers take it that way, as the same naive viewers take a film like ‘Dunkirk’ (2016) to be history when it certainly is not.

It is one of ironies of fate that most of Cicero’s many books are lost, destroyed in the debacle of the fall of the Roman Republic and then the divisions and destruction of the Roman Empire. While Plato’s works, five hundred years earlier, survived, having been widely disseminated before the collapse of the Greek world.

I have never managed to read more than a few pages of Cicero. I found him a high context writer and I did not have the context. I have looking for the copies I have on the shelf, and maybe…. My favourite Roman from this period is Decius Caecillus Metellus the Younger, who does not appear in Harris’s pages, but in the pages of the escapists series of krimis by John Maddox Roberts.

Skip to content