Martin Bora is a police officer now in the Wehrmacht, assigned to the German embassy in Moscow in 1940 from whence he is dispatched to Crete on the whim of a superior to fetch some Cretan wine. The early scenes in Moscow are interesting period pieces as the allies of convenience dance around each other.

Equally fine are the descriptions of the heat and light in Crete, after the chilly gloom of Moscow. While the weather is different, the social atmosphere in Crete under German occupation is as tense as that in Moscow.

The simple errand of finding the wine and escorting it back balloons out as readers knew it would.

The Germans have only just secured the island.

The German airborne invasion.

The German airborne invasion.

The Greeks have surrendered and the British have once again been driven into the sea, but there are still many British soldiers at large in the hills and dales, and some Cretan armed resistance has begun. It is much more dangerous than Moscow.

In the midst of this volatile situation a British prisoner claims a war crime has occurred and produces photographic evidence of the murder of a household of civilians. Hmm. Best to investigate this ourselves is the German conclusion, and do so before the International Red Cross takes an interest. It would have been a refreshing change from the stereotypes, if one of the Wehrmacht generals wanted the truth to root out indiscipline among his men. Instead it seems one of the victims was an acquaintance of the egregious Heinrich Himmler (1900-1945) and the quickens the pace.

But with Crete largely subdued and the demands of the next offensive now in train, combat troops and field officers are being transferred and reassigned in rapid succession. Ergo the only Wehrmacht officer of sufficient rank with relevant experience who is not subject to a movement order is …Martin Bora.

It is a good set-up. Bora does what all good plods do and interviews the accuser and at the end of one of their discussions when they have sparred is a nice touch. Both are highly educated men and Bora speaks perfect English so has no translator, though there are guards present and many other prisoners milling about. The Brit decides to reveal a secret to Bore to help in the investigation but swears him to secrecy. Then just to make sure the word does not leak out he switches to Latin to provide the clue. Bravo.

Bora meets a local police officer who is resigned to German hegemony and an American archaeologist, a woman, becomes his unwilling guide. Both of these characters are rounded individuals.

To find an eye witness to the events shown in the photographs in the battered camera, Bora takes to mountains of the interior to find a British soldier who allegedly fled that way. In the course of this trek the descriptions of the flora and fauna, the heat and the light are excellent but they become repetitive and thereby frayed.

It is a long way from the tourist resorts now on the coasts.

It is a long way from the tourist resorts now on the coasts.

Less palatable to this reader is Bora’s incessant need to feel sorry for himself, and bore the reader with his back story. How a solider who went through Poland and then France can be so inward looking is the mystery here. This is no Odysseus!

That he and the woman guide are at odds is well done, and unusual in this genre when the femme is usually either a fatale or a conquest. This one is not very femme though she does try to be fatale.

Bora’s meetings with those who have fled to the mountains and those who live there are uneven. The Catalonians he finds there are a cardboard plot device, period. Ditto the distant maidens in the field. Hardly more credible are the Cretan guerrilla band members. More convincing is another archeologist whom Bora finds at a dig in the mountains. Major Busch, Bora’s immediate superior, is also credible.

That Bora begins to think he is on an Homeric odyssey just seems silly. Likewise the resolution of the plot coiling back on itself is so far fetched it would take Apollo astronauts to bring it home. It is not what Aristotle would call a coherent plot.

By the way, the description on the Amazon web site, from which I acquired this book, errs on two counts. It is a not Red Cross representative who is murdered. Nor is Bora sent to investigate the murder, rather he is there when an investigation is needed and he is put to work.

Ben Pastor

Ben Pastor

This title is part of series. Ben Pastor is a woman, one who writes about soldiers, she proclaims on her website.

Author: Michael W Jackson

‘The Man from Berlin’ (2013) by Luke McCallin

Captain Gregor Reinhardt continues to struggle with his conscience in this entry to a police procedural series set in the German Wehrmacht in 1943. He is Abwehr officer, that is, Wehrmacht intelligence service, whose usual task is interrogating prisoners of war. He talks to them rather than beating them, and his makes him odd, but he gets enough results to be insulated from critics, though they circle. A successful detective in Berlin he entered the army to escape the thugs that the new regime of 1935 promoted, and its racial approach to identifying villains. Some escape.

He is in Sarajevo going about his business, trying to focus on the main things and ignore…. [much].

But he is despondent and depressed, his wife has died and he is estranged from his only son who has become a super Nazi. Is life worth living in this Dantesque universe, he might have asked, for he is learned, but he did not.

Then he is assigned a case to investigate and the old policing instincts are aroused, and he has a purpose each day. He meets the usual obstacles and obfuscations readers expect though they are heightened in this Balkan inferno. He presses on, though there are doubts. He meets some truly despicable people, including one of the late victims, a beautiful young woman film-maker who enjoyed torturing Jewish women in front of their children before filming their murders by her Ustaše comrades. If the supply of Jews was low, she would turn to Serbs for such fun.

The book offers a socio-politico topography of war time Yugoslavia, the Chetniks, the Red Partisans, the Ustaše, the Croat Army, the Italian occupation force, and the German, within whose ranks are many deep divides. Only the Italians seem to be civilised and they are a minor player. These groups make shifting formal and informal alliances. In the brew come some British advisors so the plot thickens.

It is a murder that Reinhardt must investigate. One of the victims was the woman film maker and that would be left to the civil police in the puppet state of Croatia, but also murdered a few steps from her was a German army lieutenant. It becomes a joint investigation with the Croat police for whom all acts of villainy, apart from their own, are done by Jews, Gypsies, Serbs, or Reds. Ergo find the nearest Jew and that is the culprit.

This plot is very thick and it just gets thicker. There is much about the city of Sarajevo, its Ottoman and Austrian pasts, its troubled present, and its byways. The divides among the Germans are many and varied. Their are personal animosities, unit competitions, status consciousness to an insane degree, service rivalries, venal as well as moral corruption and incompetence, and the usual assortment of thugs and bullies assembled by krimi writers, most of them wearing uniforms in this instance.

The comeuppance of the primary bully was a delight. (Where do I get one of those Reinhardt specials?) There is also a captivating portrait of a German general with something of Erwin Rommel in him, a war lover. He is in a word, charismatic. Even the jaded and cynical Reinhardt feels the urge to follow where this man leads but tries to resist it, and then realises all is not as it seems. The blue herrings are piled up and neither of the short-priced favourites was the perpetrator. That is enough of a spoiler.

The story Reinhardt tells of one of his famous cases in Berlin is nicely done. He tells the story but suppresses much of the truth, which will sound familiar to anyone who has worked in a large organisation, the backsliding, the backstabbing, the blinding incompetence, the stubborn resistance to the obvious, the incapacity to act in a coordinated fashion. The usual. Then add to that the racial elements and the brew goes from noxious to toxic.

This is the third novel I have read of late featuring such a military police office. Perhaps inspired long ago by ‘The Night of the Generals.’ That is not counting Bernie Gunther whose career I have not followed.

Perón: A Biography (1983) by Joseph Page

Juan Perón (1895-1974) dominated the political life, and more, of a large, diverse, far flung, and advanced society for two generations, and even today his name is magic for some Argentines. He did so without coercion or force. His rule was authoritarian but not with a gun, and at least in one moment of truth when he was urged to order combat to save his regime he refused.

Ergo while he might, on some grounds, be classed with Hitler, Franco, Stalin, or Mussolini no one ever imagined such restraint from them. Moreover, while he did everything to hamstring critics and opponents, they were not rounded up and sent to Patagonia or worse on an industrial scale. Indeed, at times he boasted of the freedom conceded to his critics. If at times that was more lip service than reality, it is still not something that those others would not have done.

Nor did he unleash a social revolution to purge the society of undesirables as the dictators did. Rather he tried to balance the contending forces, seeing himself as a conductor. Indeed, he liked to be called El Conductor. The orchestral image is intentional for he always liked orchestra music for the way it blended the diversity of sounds and instruments into a smooth whole. At the start that was his aim though at the end things spiralled out of control.

Finally, there is no doubt that in his early years in government, first as an eminence gris, then a Vice-President, and then President, he had a social program to redistribute wealth to urban and rural workers. To do that he more or less created labor unions in Twentieth Century Argentina.

He was born in 1895 under the sign of Libra. As a youth he lived with his family in Patagonia for several years where they worked the land before attending boarding school in Buenos Aires. He was a poor student and on a schoolboy dare took the entrance examination to a military academy. He passed and took it as a way to escape another poor report-card from the boarding school.

He liked the order and regularity of the army and soon found himself an officer where he excelled at instruction. At the time he was popular with subordinates because he was considerate of their dignity. When a private proved inept or a made a mistake, there was no shouting or punishment. Rather, after the unit was dismissed he could call the malefactor aside and give him one-on-one instruction or correction and encouragement. This was so odd that his own superiors wondered if it disqualified him from advancement, on the other hand his unit performed above the norm, and so he continued in the army.

He travelled to Europe in 1938-1939 to visit Italy and Spain. He admired the social mobilisation and energy he saw in Italy, in contrast to the disarray of France through which he passed. He attributed the virtue of Italy to Mussolini and the disorder of France to democracy. Even more striking to him was the devastation and hatred he found in Spain; that the Spanish had nearly destroyed their own country and were so divided that they hated each other more than any external enemy left him with a lasting memory. The biographer suggests that is one reason he did not resist the coup d’état that ousted him. He had no wish to start a civil war.

The Argentine army often interfered with civil life and government and in 1929, while a young colonel, he was directed to settle a wildcat strike. He did this by negotiation and not with rifles. Odd again, but success was enough.

Later in yet another military government, someone had to be secretary for labor, a minor post at the time, and because of his success with that strike he was appointed. Rather than repressing trade unions, as other Latin American military governments did, he set about creating them. He sold this approach to his superiors and their oligarchical supporters on the ground that, while it would redistribute some wealth through wage settlements, it would produce a profitable stability in which most of the wealth would remain in the hands of oligarchs. He was quite a salesman and he prevailed over much resistance. Likewise he sold the unions to labourers as a new benefit that could be achieved now.

In this marketing campaign he perfected two techniques he would use ever after. First, he set so many hares running there was confusion among his opponents. He encouraged the formation of so many unions, that they collided with each other, and he become the umpire of their disputes. Second, he learned to play his opponents off against each other because the oligarchs were not homogenous and he saw rifts among them, and likewise within the army.

There was third technique that came later and that was simply to deny everything and start over. Like an athlete, he did not dwell on failures or mistakes but pressed on.

He might have laboured at this level for the rest of his days but for an act of god. A terrible earthquake destroyed whole cities and killed thousands in 1944. The military government had to mount an emergency relief effort far beyond its own means. Civilian help was required. Who was the man of the hour? The man with contacts among all of the unions of truck drivers, entertainers, stage hands, waiters and cooks, stevedores, nurses, porters, water engineers, sanitation workers, and other working stiffs? Came the hour; came the man.

He threw himself into the work and in those days he had a very competent office staff to shoulder the task. In no time at all a whirlwind of aid developed. He went further.

Giving a blood donation made him think of using a thermometer to chart the collection not only of blood donations but also money and two large symbolic ones were erected in downtown Buenos Aires.

To raise money and blood, gala performances by entertainers of all kinds were staged before them. He attended the inaugural event, resplendent in a white uniform, modelled on those worn by Red Cross officials, and that is where he met Eva Duarte (1914-1952).

He was called the man with the toothpaste smile.

He was called the man with the toothpaste smile.

The story goes she was one of many in a group of twenty sitting far away from Perôn at the start of the evening, but by the end they were side by side and stayed that way for the rest of her life. He had a knack for publicity with his ready smile and quick wit. She added to that timing, contacts in show business, and a sense of the dramatic. They were a power couple par excellence from that night onward.

Juan and Eva.

Juan and Eva.

The generals pushed each other into and out of the office of president, and one such elderly general left most of the work of president to his aide-de-camp, Colonel Perón, who remained simultaneously the secretary of labour creating a working class constituency for himself. That may be the wrong way to say it because there is no sense that he was planning ahead. Rather he found the exercise of managing events fascinating and discovered he could do it.

Then he was Vice President and in that position ran ever more of the government. His programs built roads and bridges to allow crops to reach cities at affordable prices, social insurance, hospitals and schools, severance pay, accident insurance, and more. He had no ideology but he saw in such measures stability and harmony.

Eva’s influence led to reforms concerning women and children, including, in time, the franchise, divorce, and creches. While he was an average public speaker, she was a firebrand and she became the voice of Perón. He was measured and rational; she was immediate and emotional. Together they covered all bases and they often spoke in tandem.

At times these benefits were reduced to meet other economic goals and he spent a lot of time explaining this to those affected. Our author suggests that in other circumstances he would have been happy to be a teacher since he enjoyed such exercises.

He made enemies, of course, and the ride was rough at times. He masked his efforts behind the smokescreen of a myriad of projects and activities. Confusion was his strategy. Divide and conquer was his tactic.

When an incumbent military government went through the motions of an election to placate world opinion and attract foreign capital, he became a candidate and the Perón and Eva combination overwhelmed opponents. He got two-thirds of the vote. He was aided by the clumsy efforts of the US ambassador to defeat him. Perón added the anti-American card to his tactical arsenal.

The suspicion existed that Perón was a fascist. His influence then explained why Argentina stayed out of World War II for so long. Leave aside the fact that Argentina had no interests involved in the war, apart from satisfying the United States. That there was a resident German colony of long standing in Argentina, come originally for engineering projects, was used to explain how he learned his fascism. Leave aside the fact that he had nothing to do with them. That together with public admiration for Mussolini’s Italy as he saw it in 1938 was conclusive in Washington.

In 1944 while the war in Europe continued no expense was spared in Washington to research captured German records to find something on Perón, producing a Blue Book that contained nothing of substance. I noticed some of this was recycled lately from copies of the same German records seized by the Soviets. The one part I read had Perón instructing Argentine diplomats to encourage French citizens who did not want to continue living in France or to return there to migrate to Argentina. He also encouraged the local German community to recruit technically skilled Germans to start over in Argentina. How damming was that! He personally did not stamp Eichmann’s passport, honest.

One of the hallmarks of European fascist regimes was social revolution that changed the society, usually by genocide or proscription. There was never any of that in Perón. On the contrary he liked diversity, the better to play one part off against another.

As president Perón put a lot of pressure on British interests, which were deeply rooted in Argentia, especially in the railroads. He did nationalise some British assets but also paid off a billion dollar debt to the Bank of England at the same time. He created marketing boards for crops and some industrial products that would negotiate international sales. One was the Argentine Wheat Board later to be the unstated model of the Australia Wheat Board.

None of this was programatic and that needs to be born in mind. He had no ideology. He just tried things, and if they worked, then fine. If not, he walked away to try something else. He had a capacity to recognise defeat and quit, unlike the ideologues today who keep trying the same thing again and again, willing it to work despite the costs.

In the Cold War he was a vigorous anti-Communist not as a matter of principle so much as because it was foreign and godless. He tried his hand at international statesmanship by giving speeches in Chile and Brazil about a third way between capitalism and communism. Capitalism in the much of South America was identified with the rapacious practices of some American businesses, and communism was anathema to Roman Catholics. He had a tin ear for diplomacy and soon gave it up.

Thereafter sports was the one field in which he promoted Argentina on the international stage, and the bid of Buenos Aires for the 1956 Olympics was defeated by one vote, and the games went to Melbourne.

He promoted economic independence in the post war world and shunned the Bretton Woods agreement that created the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the International Monetary Fund. While Great Britain owed Argentina huge sums for food imported during the war, it could not pay in hard currency. Some of this debt was offset again the British owned railroads.

Inflation beset Argentina and Perón had no remedy. Belt righting by workers was a help but not enough. Higher taxes on wealth helped but not enough. And each of these measures made enemies.

He won a second election in a campaign that was heavily restricted. Only in the two weeks before the election were political parties allowed to exist and campaign, and by then radio and newspaper were either controlled by the regime, some owed by Eva, or obedient to it.

‘La Prensa’ was a newspaper the regime targeted and one that fought back. Its resistance to the censorship of the regime, and physical attacks on its plant, rallied the international press to its side. The irony is that at the time ‘La Prensa’ was a rag (think News Limited) that supported the oligarchs but all this international attention somehow caused its writers and editors to live up to the image of embattled heroes of free speech and ‘La Prensa’ became, thereafter, as a result of this ordeal, a very fine newspaper. Something it had not been before.

A few numbers might indicate the scale of activities in his first two terms. more than 4,300 health care facilities were built and staffed. There were 8,000 new schools with teachers, and several hundred technical institutes to train nurses, mechanics, midwives, and others. More than 600,000 homes were built for low income families.

Investment was also made in industrial projects like dams and harbours.

Eva Perón created a foundation and Juan directed that a one percent of the national lottery funds go to it and influenced (ordered) the tame trade unions to see to it that their members contributed to the Foundation one day’s pay a year. The Foundation employed 15,000 people to run clinics, transport midwives, build old-age home, workers holiday resorts, build playgrounds, orphanages, and create soccer leagues. To play in the soccer leagues the boys and girls had to have a physical examination by a doctor, the first time for most of them. At practices and games they got a hot meal designed by dieticians. The Foundation paid for all of this.

She was on track to be his Vice President when cancer laid her low. Her death and the subsequent treatment of her cadaver are the stuff of legend. Juan was rendered speechless for days after her death. He who had hardly ever had a sick day refused to believe she would die, until she did.

The inescapable conclusion is that even before Eva’s death, Juan had grown bored with politics. He needed a new challenge, hence the dabble in international statesmanship, and so he provoked a conflict with the Catholic Church. It was needless, but once it started he went at it hard. proposing to tax church property. Churches were burned by some of his enthusiastic supporters whom he encouraged, though did not direct. This was madness in the confessional society that was Argentina.

His enemies who had been squabbling among themselves for years, now united behind the church. No sooner was he re-elected, in 1952 another coup succeeded. Several earlier ones had failed due to rivalries among the plotters.

There is no doubt that the Perón regime had its ugly side. Thousands of teachers were dismissed because they were insufficiently enthusiastic about Perón. More importantly, Peronism changed from measures aimed at social harmony to measures aimed at keeping Perón in office as an end in itself. The means had become the end. One of the strengths of this study of the man is that it shows how he changed. After ten years he no longer felt the need to sell his ideas. He just gave orders. He did not have the instincts of a democrat.

And Perón wanted to stay in office, not to accomplish anything in particular, but to continue to play the politics game.

To his credit, however, Perón did not fight the coup, though there were armed Peronist militias ready to do so, and he had still many army supporters in the lower ranks. Instead he went into exile. The shadow of the Spanish Civil War remained with him.

Despite all the rumours circulated by his domestic and international enemies he had no ill-gotten fortune. He lived on the largess of his hosts in Paraguay, Panama, Dominican Republic, Venezuela, and finally Spain. That is one reason way he moved on each time, his welcome was worn out. The new Argentine military regime spent millions of pesos to eradicate every vestige of Juan and Eva Perón. Teachers from Patagonia to the Amazon basin spent one summer blackening their names out of textbooks. Street names were painted over. Statues destroyed. Back files of newspaper were burned. The Mausoleum to house Eva’s embalmed remains that was under construction was demolished overnight to become a carpark.

Then Argentina went through a long period of instability with coup and counter coup as the military factions brought order and discipline to the society! If the succession of musical chairs military governments promised stability, they did not deliver it. One president after another came and went. Planes bombed the presidential palace on occasion.

Naval personal kidnaped a president. Another was assassinated by a rival’s supporters. On it went.

Civilians took up arms, too, some encouraged by Perón from Spain. He termed them ‘special formations.’ Once off the leash, they stayed off the leash.

Five years after Perón was expunged from Argentina, a military government made tentative steps towards civilian rule through elections, as much to placate foreign investors as to satisfy domestic demands. From exile in Madrid, Perón advised his followers to cast blank ballots. They did and that was the plurality result, about 30%. In the rush to appear democratic that fact was ignored and a civilian government with 25% of the vote was installed and it fell at the first feather. The generals returned.

Peronism — with or without Perón — came to dominate Argentine politics. There were first those who were anti-Perón, the land owners, industrialists, bankers, intellectuals like Juan Luis Borges, and much of the older generation of the army who felt he had betrayed the uniform by siding with workers who were all closet communists. That was one-third. The Peronist made up the other other two-thirds. One portion of them were ideologues who saw a program in what the Peróns had done and these became the left-Peronistas. Another portion became followers of the man himself. Whatever Perón says goes. It was a messianic cult as much as it was a political bloc. These were the right-Perónistas. In between were the trade union moderates who concentrated on the sewer socialism of wages, accident insurance, and medical coverage. (The term ‘sewer socialism’ is explained in an earlier post on Milwaukee.)

None of these positions was satisfactory and in the 1970s the fissures opened. A wave of urban guerrilla warfare arose with the Montoneros and then their rivals. There were also armed labour factions that battled out union elections with bullets rather than ballots. Foreign investment disappeared. Inflation ran out of control. Strikes were daily. Infrastructure repair ceased, as did buses and trains. A flight of capital occurred allied with a brain drain.

In this turmoil another general-president looked to Perón for help. No doubt this general overestimated Perón’s potential influence, but Juan Perón was not going to disabuse him. Courtship was undertaken. Perón was rehabilitated, given an Argentine passport, his back pay and pension were resumed, his statue appeared once again in the line of presidents in the official residence. (What a line-up that is, since one held the office for two days and an another for two weeks between coups.)

While in exile Perón had long continued his game playing by mail, by telegram, through emissaries, while those who aspired to bask in his glow travelled to Madrid at their own expense for an audience with him.

Presidential elections occurred and Perón’s handpicked candidate, Hector Cámpora, a dentist, won a resounding victory. Perón returned, Cámopra resigned, and in new elections Perón won again, a third time. This election was much more fair than the last one in which he triumphed, but his win was just as decisive.

While exiled Perón had met Isabel Martinez (1932+) and married her. She too was a performer and bore a slight resemblance to Eva before cancer took its toll. He was 66 and she was 30 and looked younger. In no other way was she like Eva. Indeed she was very insecure about her place in Perón’s life.

Early in his career the dynamic Perón had attracted a lot of capable people and put them to work. Gradually he shed most of them, because he wanted to be the master of the situation not upstaged by any minor players, still less to nourish a successor. His entourage then swelled with acolytes, yes-men, toadies, and the like. He had little or no interest in these hangers-on but took their service – door opening, bodyguard, floor sweeping, typing, housekeeping, dog walking, telephone answering, car maintenance – for granted, though he was unfailingly polite to one and all. For an Argentine a few months in the Perón household could be translated into celebrity back home. There was never a shortage of volunteers who paid their own way.

The chronic instability of Argentina and the extremes of the military governments attracted much attention from Washington during the Cold War, lest it become another Cuba. The American interests could never find evidence to support the charge against Perón that he was a Nazi or sheltered war criminals despite much effort, nor could they ever find the illicit millions he had allegedly drained from Argentina. He lived modestly in Madrid, dependent on admirers and the Franco government. Later when his army pension was restored he wanted a lump sum for the back pay to settle debts. Though, by the way, Franco choose never to meet him in the twelve years Perón spent in Spain.

He returned to an Argentina that was demoralized, broke, and riven. Armed bands roamed the streets looking for trouble which they found. The damage done in the last coups, shell holes in buildings, and wrecked vehicles were left in situ. The army was torn by personal rivalries and enmities. After years of repression few civilians ventured into politics. It was a devil’s brew.

Yet Juan Domingo Perón became president for a third term at age 78. For comparison Ronald Reagan took office at 70 and left at 78. Perón’s heart was poor but this was concealed from nearly everyone.

The touch he had had in years gone by remained. While he could match the contradictory confusion of Joh Belke-Petersen, he had no plans and no staff to execute them. He tried to rein in the violence, much of it done in his name, by meeting leaders of the factions but without success. It was as though all waited for a miracle.

Eva’s body had an odyssey of its own. When the putsch ousted Perón plans for her mausoleum were shelved, but the body had already been embalmed for display.

No one wanted to be the one to destroy it, so it was boxed up and left in a basement marked as ‘Radio Parts.’ When a new building manager came along later, not knowing what was in the box, he moved it into a hallway to make use of the space in the basement. There it sat. By this time those who had boxed it up were displaced, some killed by rivals, others themselves in exile. Then a new Minister took office and wanted to reorganise the building. The box was a fire hazard in the hallway. He ordered it moved. To move it the workmen decided to open it. Surprise!

The box was quickly sealed and put back in the basement while the matter went to then president. Before he could act, there was another coup and there followed another pause. Then it was decided to bury her, but not in Argentina. The body was transported to the Argentine embassy in Rome and then buried in Milan under her mother’s name.

Were she buried in Argentina the location would inevitably leak out and then most likely become a site of pilgrimage for Peronistas. Hence the decision to send the remains abroad. Argentina had good relations with Italy so blind eyes were turned and the deed done.

When a moderate general=president restored Juan’s citizenship and pension, the general-president also arranged for her body to be disinterred in Milan and delivered to Perón in Madrid who accepted it and put in an unused bedroom upstairs, where it stayed even after he returned to Argentina with Isabel.

While the body was in the bedroom, one of the entourage who dabbled in Brazilian black magic convinced Isabel to take part in seances, let us call them, to conjure Eva’s spirit into her own body. The individual in question was certainly nutty enough to do this and Isabel was very easily led, so she may have played along in the hope of securing her position as Perón’s paramour. (Argentine’s are quick to label anything they dislike as Brazilian.)

Shortly after the third election Perón had a serious heart attack, that sapped his vitality. It seems to have been a spontaneous gesture by his supporters to put Isabel on the ticket with him as Vice President and he had let it ride.

Isabel.

Isabel.

The author is sure it was not his intention to elevate her because he was using that card to tempt and control rivals. That dabbler in the black arts, Daniel José López Rega, became his personal private secretary and controlled access to the man himself.

He was 73 in this photograph. Hair dye?

He was 73 in this photograph. Hair dye?

Perón had no new cards to play and the 1973 oil shock hit hard. The armed conflict continued, mostly between the ideological left Peronistas and the trade union Peronistas. Many believe López Rega formed the first Death Squads and turned them loose on one and all. Rather than peace and stability, Perón’s return led to an escalation in violence.

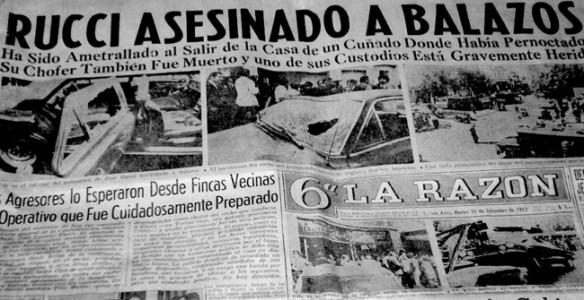

Yet another murder.

Yet another murder.

He worked hard in his third term, but to little avail. Then in June 1974 he had a series of heart attacks and on 1 July 1974 he died. Millions mourned Perón. Isabel succeeded him, and she was heavily dependent on López Rega and the state terrorism became systematic. The Dirty War had begun. In March 1976 yet another coup d’état displaced her. By the way Amnesty International estimated that the Dirty War killed 30,000, imprisoned a multiple of that, leaving them scarred, and intimidated most of the population. Though what is was about is lost in the mists. It became score settling as end itself, and discredited most state institutions, the police, the army, government officials, and school teachers for the subsequent two generations.

A crowd to hear Eva speak.

A crowd to hear Eva speak.

The word ‘charisma’ is so overused I am reluctant to employ it but that does seem to be the word to use here. Juan bore a message and for a while subordinated himself to it. Eva added an emotional touch to that. It was interpreted as a message of hope by the rural and urban working classes. He delivered a lot to them, certainly more than ever before or after. It is estimated that about a third of the nation’s income was redistributed, directly in income, to these peoples, and more indirectly through the social welfare programs.

He also had John Ford luck, a phrase from Hollywood that explained why the sun always shone when Ford scheduled out door filming. When Perón had an outdoor rally it never rained and always shined. So it was said. He was personally attractive and a tireless worker.

But his luckiest break was to be in exile when all the wheels fell off, so that he was untouched by the endless corruption and conflict of that seventeen year period. Though experienced and connected he returned with clean hands.

On the debt side is his later preference for sycophants and his willingness to encourage violence, perhaps on the mistaken assumption he could quell it with a word. He could not.

He was an authoritarian populist who did deliver to his supporters, but less and less. He gave no thought to succession. Isabel was in way over her head. Unlike Salazar of Portugal, Perón was bored by routine. He never quite had the grip on sprawling Argentina that Salazar had on compact Portugal and so devoted an inordinate amount of his time to securing his own position and over time that displaced any social or economic goals.

No doubt there are those who know this era of Argentine history better than do I, because they have seen the movie! But I am reminded of the film reviewed elsewhere on this blog, ‘The Secret in Their Eyes’ which offers insight into Argentina after the ‘Dirty War.’

This is an excellent book. Carefully phrased, thoroughly research, slow to judgement, and measured in expression.

Joseph Page

Joseph Page

Chapeaux!

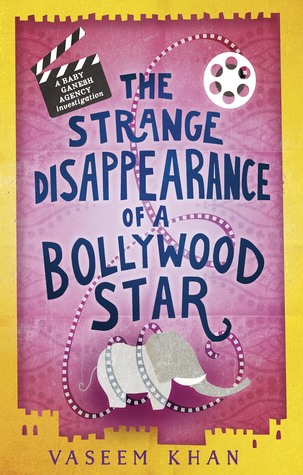

Vaseem Khan, ‘The Strange Disappearance of a Bollywood Star’ (2017)

The third entry in this perfectly charming series set in contemporary Mumbai, a world rich with colour and incident.

The plot? A spoiled brat of a Bollywood star is kidnapped, and the stops are pulled out to get him back, to save the blockbuster movie he is starring in, to satisfy his doting mother, to avert a massive insurance payout. There is only one man for the job in all of India, of course.

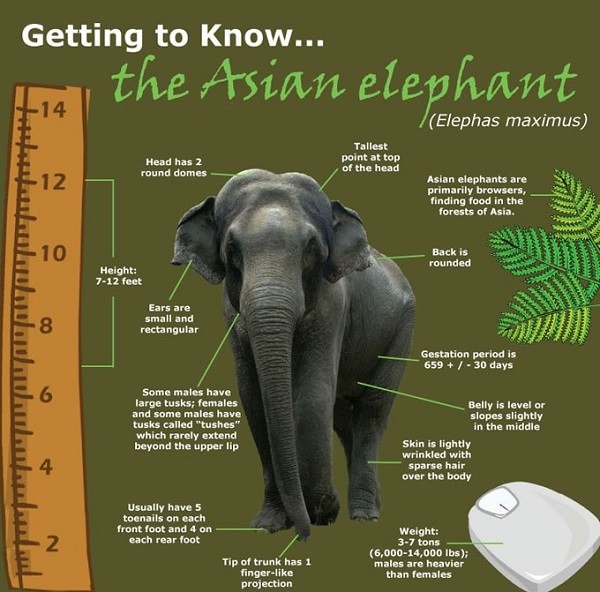

Chief Inspector Chopra (Ret.), enemy of all crime, and his sidekick, Ganesha, the little elephant, get the call. Everyone knows about police dogs, well Ganesha is a police elephant!

The Asian elephant.

The Asian elephant.

In Bollywood, nothing is as it seems, and Chopra swims through many blue herrings to end up back where it all started. Reality is even more unlikely than the cinema!

Along the way there is much to’ing and fro’ing in Mumbai and a cast of many. Holy days upset the schedule, and Ganesha finds the vital clue and also saves Chopra’s life again. Once more Ganesha proves to be no ordinary elephant.

Meanwhile, Chopra’s trusty assistant settles his own case among the lowest of the low in the Indian caste system, the eunuchs, and learns some things about himself in so doing.

The lowest of the low.

The lowest of the low.

In addition, Poppy, Chopra’s wife, rises to the occasion by staging a daring jailbreak, aided by the ever reliable Ganesha, and the chef’s number two curry! Poppy runs a restaurant and she recruits the chef for the heist. Chopra refuses to take money from friends, so when he needs help, they turn out in force.

Poppy, earlier, made an alliance with the officer who replaced Chopra at the nick, a very belligerent woman, but once she is on your side…. Get a flak jacket!

Then …… That is a spoiler. Delete that.

It works out in the end, though Chopra’s nemesis Deputy Commissioner Rao is not done yet. That is clear. This is a tale of redemption, and ends with Ganesha doing a star turn.

Vaseem Khan, away from the keyboard.

Vaseem Khan, away from the keyboard.

‘7th Cavalry’ (1956)

The ‘7th Cavalry’ (1956) is about the aftermath of the Battle of Little Big Horn in June of 1876 when many plains indians united in the Great Sioux War. George Custer led his seven hundred troops into a trap of which he was warned by scouts and against the objections of subordinates. Though dead when this story starts, Custer’s pall lies over it all. He is lionised as a great leader, soldier, general, man, and paragon down to his yellow hair. On him more at the end.

Lobby poster.

Lobby poster.

The story is a combination court room drama, star crossed lovers (for once Scott gets the girl), dissension in the ranks, and a culture clash.

The tension arises because Scott was sent on leave by Custer just before he set out for the valley of the Big Horn River. It was verbal order and in a subsequent inquiry the suspicion arises that Scott had deserted and is lying about the order. (How anyone could believe for a nanosecond that Scott would do something so dastardly beggars belief.) The result of the inquiry is inconclusive.

Then comes an order from distant Washington D.C. to retrieve the bodies of the now honoured dead. Gulp! The war is on and that is a battlefield. There are seven hundred dead, only a few hundred remain in the fort, demoralised, frightened, and confused without the great Custer.

Who will do it?

I’ll go.

I’ll go.

Scott steps forward. (Of course.) He’ll go where the others fear to tread. With a detail of a few misfits not otherwise needed by the garrison, off he goes, tall in the saddle as always. The misfits include J. C. Flippen, Frank Faylen, and Denver Pyle. Familiar faces all. How this handful of misfits is going to bury hundreds and cart home the remains of the officers is anyone’s guess.

There are many vistas of the Alabama Hills where it was filmed, and much dissension in the ranks, which Scott deals with – wallop. Denver Pyle is ever reliable as a malingering whiner.

The high point of the picture is the negotiation at the Big Horn with the Sioux, who are forbearing, dignified, and conscientious.

The negotiation.

The negotiation.

The Sioux belief that the spirit of slain enemies nourishes their strength means the dead must remain in situ, especially Yellow Hair, the leader. Hearing this explanation from a Christian mission-reared Sioux, Scott says, ‘but you know that is all superstition’ to which the Sioux replies ‘just like your Christianity.’ Scott offers no reply. Superb. A moral and intellectual standoff between two well-meaning individuals who are now on a collision course.

Spoiler alert! Though guns are drawn and arrows slung, an ominous silence reigns. What Hollywood director would dare do that today? Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse have no wish to desecrate the field, but neither will they relinquish the bodies.

For the denouement have a look on Daily Motion.

It is a loose end that the messenger whose testimony finally and fully exonerates Scott does not seem ever to have delivered this testimony, and is killed without a comment. It was Harry Carey Jr.

George Custer had a great press, partly because of the efforts of wife and widow. He was careless with the lives of his men throughout his career, though of course he took the same risks himself, if that is any consolation. In the spring of 1865 when the ghost Army of Northern Virginia manoeuvred out of the deathtrap of its trenches at Petersburg, Custer ordered his cavalry division into a frontal attack on a scant division of emaciated infantry under Richard Anderson’s command.

Think about it. Men on horseback at a distance of several miles array in a line and then gallop over water courses of a wet spring and scrub bush toward a line of infantry men who, seeing them far off, had enough time to build defensive breastworks of fencing and wagons, unlimber and aim artillery, and to lock and load, take aim, and fire, long, long before the horsemen get close. An infantry musket had a killing range of five hundred yards. In the hands of a marksman the range was as much a 1,200 yards.

The feeble grey infantry killed a great many mounted bluecoats and broke the attack. It was madness. Custer’s command had the latest repeating rifles but even if an trained horseman could handle the weapon while galloping, the chance of hitting anything were near zero and reloading once the first seven shots were fired was impossible at a gallop.

The advantage of numbers saved the day, and the headlines, for Custer. His vastly larger force withdrew and flanked the Confederate line and compelled a withdrawal. How much better it would have been for the widows and orphans of the men in his command if the flanking move had preceded, and thereby obviated, the frontal attack. There was no Tennyson to immortalise this catastrophe. Yet the Custer publicity machine turned it into a great victory for him at Little Sailor’s Creek.

‘Ride Lonesome’ (1959)

This might be the best of the seven Ranown (Boetticher-Brown-Kennedy-Scott) movies. Why? The complexity of the plot and the surprise ending. Well, it surprised me and I thought I knew the formula backward. In fact, the end, the last scene is most fitting, though it left me wondering about a few things.

A lobby poster.

A lobby poster.

It starts as the usual story. Scott is the cryptic loner who appears from the dust to aid the damsel, Karen Steele, in distress. He has in tow the murderous James Best, who, as always, makes one’s skin crawl with his servile, whining, inept, craven villainy. Moreover, Scott with Best and Steele falls into the company of a dubious pair, played superbly by Pernell Roberts and James Coburn, both outlaws themselves but not in Best’s class. The shadow of a future confrontation between this pair and Scott is obvious both to the viewer and to the parties. This was Coburn’s first film role.

Roberts and Coburn confer.

Roberts and Coburn confer.

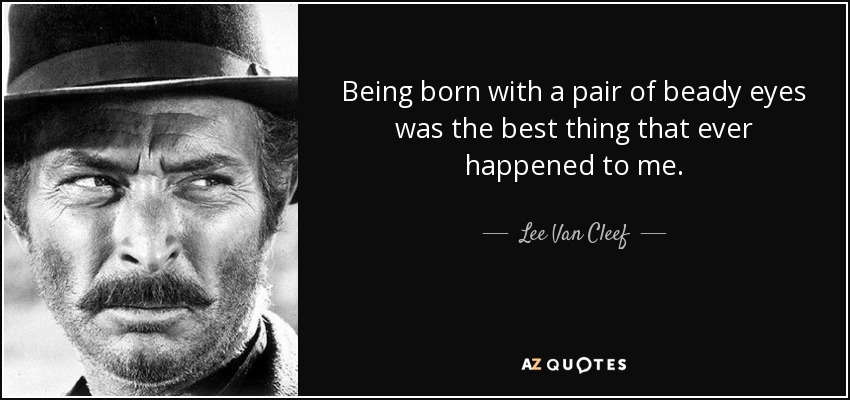

Best brags repeatedly that his big brother, the redoubtable Lee van Clef will be coming to his rescue and kill them all. I would certainly fear Lee VC, as he liked to be called.

Lee Van Clef on his film career. Regrettably most directors asked no more of him than to squint those beady eyes.

Lee Van Clef on his film career. Regrettably most directors asked no more of him than to squint those beady eyes.

Before that confrontation they have to elude the raging Mescaleros, Apache Indians, who are raiding and have killed Steele’s husband. This is one occasion in the series when the indians are a mere plot device and given no explanation. This party of five had better make tracks to escape the indians and Van Clef.

Yet, at Scott’s insistence, they take the long way, travel in daylight, and cross open country rather than sticking to tree lines and ridges, moving at night. No effort is make to cover their many tracks. It dawns on Roberts that Scott wants to be caught, not by the Apaches, but by Lee van Clef, because…

Roberts and Coburn have a powerful incentive to take Best away from Scott and deliver him to the law, for then they will gain amnesty for their own earlier and lesser crimes, and so be free to live an ordinary life. Roberts is magnificent in wrestling with this temptation. Understated and taciturn per the screen play but endowing it with depth and delivering it with timing. Coburn as a naif is the perfect foil to his ruminations.

Scott never has doubts and so never ruminates: Best is a murder and he must be delivered. He is Scott’s prisoner and so he will deliver him. End of story.

Well not quite because there is a confrontation with Lee Van Clef, the one villain in this series who is not fleshed out but left a cypher, as Van Clef usually was.

Then comes the surprise.

Then comes the ending.

The end.

The end.

‘It figures,’ says Roberts in another of his diamond lines tossed over his shoulder.

‘Comanche Station’ (1960).

My homage to Randolph Scott continues, after an hiatus. This one is near the end of the series, and the formula shows through it. Scott, as ever is a loner somewhere, sometime after the Civil War in the West. Reticent, stoic, confident, straight as the Indian arrows he dodges, here he is st age sixty-two.

A lobby poster.

A lobby poster.

His path crosses that of a damsel in distress, and she finds the enigmatic Scott compelling, yet he a distant and perfect gentleman and she, usually, is another man’s wife. To spice up the mix there must be villains, and to the credit of these productions the chief villains are never Indians, though they are there, but other Europeans. The villains are thrown together with Scott and his charge in hostile circumstances and, in this case, they have to cooperate to avoid the Indians, but we all know a showdown is coming at about minute 70. We all know who will prevail, but the skill of the writer and director still manage surprises through the supporting players like the damsel and the naif.

Inevitably, the naif grows to admire Scott and the naif’s commitment of the Villain-in-Chief wobbles. Inevitably, the damsel misunderstands Scott’s motives and only gradually sees through that misconception to his noble core. Thus there are several nested stories. The overarching narrative is to survive the hostile circumstances and return to a town. Within that we have the menace and final confrontation with nemesis. Nested still more are the doubts of the naif and also the dawning realisation of the damsel that Scott is a knight without armour. When all these themes have played out, inevitably Scott rides off alone. Oh, and inevitably Scott wears a neckerchief. Don’t know why. To hide a scar?

Another credit to the production is that the villain has personality, and is not just the CGI cipher villain now in Hollywood productions. In this tale the villain is Claude Akins, who combines a rude charm with a bottomless evil.

The protagonist and antagonist discuss their differences.

The protagonist and antagonist discuss their differences.

I was disappointed to see Akins’s name in the credits when it rolled off ‘Daily Motion,’ the website from which I streamed it, because I remember the caricatures he used to play on television in the 1950s and 1960s but here he projects a distinct individual who is not all bad and yet is – in a different sense – all bad. He is aided in his villainy by the ever reliable Skip Homeier, who is knocked off too early for this connoisseur of slim-balls. The villain in this formula usually has two acolytes, and third in this party is Richard Rust, otherwise unknown to me, who is a naif who has fallen into bad company and knows no way out. The list of chief villains Scott bested in these last films is impressive, starting with the most complex, Richard Boone, Lee Marvin, Pernell Roberts, Lee Van Clef, and Warren Oates, and many others.

Indians, I mentioned Indians and they are here and on the warpath, but they are also shown to be honourable. The Comanches kept the deal they made with Scott at the outset. Moreover, that they are making war is, we learn, precipitated by the murder of many of their women and children by still other bad Europeans off camera. In fact, they are victims who are lashing out at those to hand.

Scott made at least a hundred films and perhaps eighty of them were Westerns. He got type cast but he also liked that. He rode on to the screen time after time with a self-confidence and poise born from having been through it all before, again and again. It is no wonder Sheriff Bart invokes him in ‘Blazing Saddles’ (1974).

Seven of the films Scott made at the end of his career have been the object of my veneration in this homage. Why these? Because by that stage in his career, with the astute management that made him a millionaire many times over, and too old to remain under contract to a studio, he was a free agent who could decide what he wanted to do and then do it. This he did with some long time friends and associates producer Harry Brown, director Budd Boetticher, and writer Burt Kennedy. They were made in the Alabama Hills on the east side of the Sierra Madres. Each films includes many elegiac passages as the cast travel through the area. All of them also put the life-and-death human concerns against a timeless and limitless backdrop that shows just how small those concerns are in the ultimate scheme of things.

Budd Boetticher at work.

Budd Boetticher at work.

Clint Eastwood and Martin Scorcese and others have both expressed their admiration for these films. Look for them on You Tube. It is exactly this sort of the film that George C Scott refers to in ‘They Might be Giants.’

Scott’s career culminated in one of the greatest Westerns, ‘Ride the High Country’ (1962), Sam Peckinaph’s first western, featuring a near-sighted Joel McCrea with an arthritic Scott, the ingenue Mariette Hartley, the drooling Warren Oates, and more. The gossip is that Scott and McCrea flipped a coin to see who would play which part, one a huckster and trickster and the other a pillar of unassailable integrity. Both were pitch perfect and both quit on that note. I will also sneak a peak at one of his defining films that etched itself into my prepubescent mind, ‘7th Cavalry’ (1956).

The President of the Electoral College

How is it that the USA Presidential incumbent retains the support of his voters when he acts repeatedly against their material interests?

Wake up! It is simple.

The President of the Electoral College of the United States delivers to his core supporters every day the two most important things they value. All else pales into insignificance against these two.

First, he is not a black man.

Second, he is not a woman.

End. It is primal. It is not about policy, not about politics, not about consistency, not about probity, not about government….

Politics is simple, until analysts make it complicated for their own reasons.

He also delivers to this constituency in other ways, too.

He is not an immigrant.

He does not have a foreign sounding name.

The title of this entry is taken from Vicente Fox, one-time president of Mexico, who has poked fun at Trump Donald on Facebook with more wit and zest than most others have done.

‘The Book Smugglers of Timbuktu’ (2017) by Charlie English.

The word ‘Timbuktu’ entered vernacular English in 1863 as the most distant place imaginable, according to the OED. It has had many spellings over the years but the one used here is the standard in Wikipedia. Most who have heard the word take it to be mythical, but in fact it can be found on a map, in the sub-Sahara West African nation of Mali.

Timbuktu gained some recognition among the Nerd Empire in the late 1990s for the collection of medieval and even ancient manuscripts gathered there, and more when these treasures were threatened by fundamentalists whom god had told to destroy all. Not all the nut cases are in D.C.

A building in Timbuktu.

A building in Timbuktu.

The airport at Timbuktu

The airport at Timbuktu

This book combines the Nineteenth Century story of Europeans exploring the interior of Africa to find this very place with the Twenty-First Century story of saving its aforementioned records from the flames.

The quest for this African El Dorado began in the mid-Victorian period when intrepid chaps in Britain were looking for new adventures. Africa, the dark continent, beckoned. It was called the ‘dark continent’ and ‘darkest Africa’ not because of the colour of the skin of the natives but because it was unknown, in the dark. There was plenty of racism but this term was not an instance of it at the outset. Later, yes, certainly. say as it was used in the 1950s in Disney cartoons.

In part the book traces the efforts of the African Association in London to explore, map, and study Africa, partly directed by the affable Joseph Banks, who as a young man had accompanied James Cook on his voyage to Australia, and after whom Bankstown is named, along with flora. The method this private organization took was to recruit a series of intrepid men and send them off one-at-a-time. Off they went and mostly disappeared into darkest Africa, never to be seen or heard again. Disease, dehydration, animals, sand, stupidity, accidents, villains got them one after another. Inevitably, a Société d’Afrique in Paris got into the game so that the rivalry between England and France was played out on the way to Timbuktu. Then came the Germans looking for that fabled place in the sun.

On the other hand is the story of the threat posed by fundamentalists, which is told in the choppy and breathless manner that distinguishes contemporary journalism. It is a sandstorm of names and places that mean nothing to this reader, and at no point is there an orderly exposition of what the manuscripts, papers, and documents are, how they came to be in Timbuktu, and who had formal responsibility for them. Nor is there anything more than the repeated assertion that they are valuable to justify the importance assigned to them. In the telling, it sometimes seems this town on the sand just by chance was home to a number of private collectors who had somehow gathered the written material and at other times there are references to libraries, catalogues, steel boxes, and UNESCO grants. Later there are few references that indicate that Timbuktu became a centre for learning in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries, but by then I was so lost it did not help.

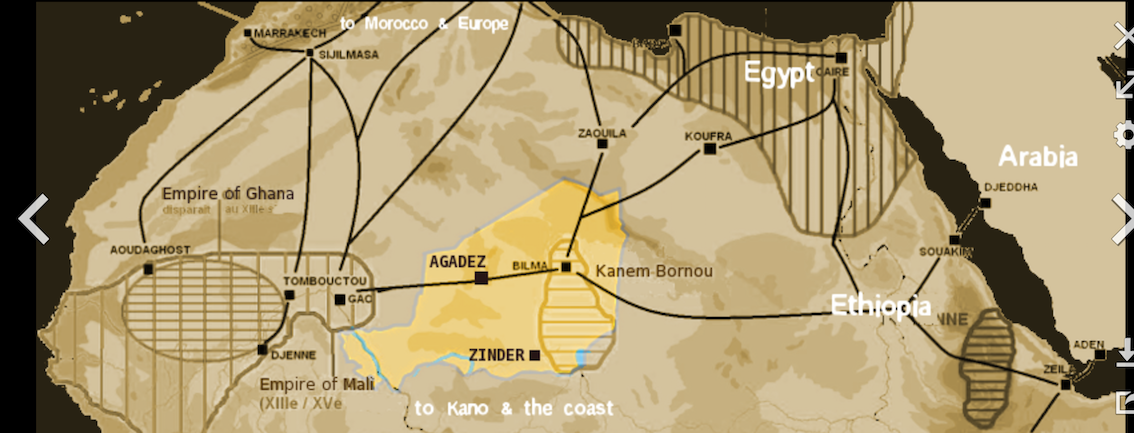

This map below from Wikipedia shows when and why Timbuktu (Tomboctou) was an important crossroads that benefitted from proximity to the mighty Niger River, from which proximity it also suffered when the river flooded. The lines are trade routes used at various times.

That combination of two stories is both an asset and a liability. It is an asset because it makes clear the importance of Timbuktu and its holdings and a liability because the author has a lot more to say about the latter story than the former and so it is unbalanced.

Trashed books in Timbuktu

Trashed books in Timbuktu

While the telling is repetitive and confusing at times, the subject is so important that I tried to persevere through all the confusion that the author reproduces.

There is a shower of proper names, descriptions of men with guns, the arrival of trucks, comings and goings as though this is a thriller. Well it is a mystery to this reader. One that remains unresolved.

Charlie English

Charlie English

I supposed the author was a journalist from the disjointed style, the disregard for readers, and the indifference to exposition, and then I checked. Sure enough. He and this book get a lot of space on the ‘Guardian’ web site. Make up your own mind. I have. With perseverance I made it about halfway through before deciding I would learn more reading Wikipedia. No doubt Good Reads is replete with fulsome comments. No doubt the dust jacket of the hardcover proclaims it a best seller. No doubt.

Dollmaker (1995) by J. Robert Janes

Inspector Hermann Kohler and Chief Inspector Jean-Louis St-Cyr, an odd couple of Occupied France, get no rest. No sooner have they nailed a culprit than a telegram arrives ordering them on an all night dash across blacked out France to another crime scene. This time it is Lorient near Saint-Nazaire. These two ports were the principle bases for German U-Boats from 1940 to 1944.

The fateful telegram came directly from Admiral Karl Dönitz, nicknamed the Lion for his mighty bellows, commander in chief of the U-Boat fleet. Dönitz became head of the government for about three weeks after the death of Adolf Hitler. The telegram was odd in that he ordered them to investigate the allegations against the Dollmaker, per the title.

It is literal, the chief suspect is a dollmaker, who is also a very successful, and still living, U-Boat commander. Toy-making was a major German business for a long time and grew especially during the Weimar period to earn export income, because there were so many restrictions of German industries and shortages of material, wooden and clay toys were made. This captain has discovered deposits of very fine clay around Lorient and dreams of reinvigorating the family business when on leave between voyages.

A very unpleasant shopkeeper has been murdered on a cold and wet winter night along a railway embankment. Left it situ, Kohler and St Cyr arrive to investigate to the great annoyance of the local gendarme commander.

The nearby stones of Carnac provide the brooding presence of eternity for the nocturnal wanderers during the long black-out nights of winter. There are thousands of stones, some to rival Stonehenge.

With the death of the shopkeeper a great deal of money also seems to be missing, the money the dollmaker raised, mostly from his crew, to invest in a dollmaking enterprise with the deceased shopkeeper. Strangely though, as Kohler and St Cyr note, no one seems now to be worried about the money.

The suspects are many. It is surprising how many people were out and about on the railway embankment at the time of the murder. There is the shopkeeper’s daughter, who was probably spying on him for her crippled mother. There is a woman married to a musician who has gone silent. She may have been looking for her husband who roams the stones at all hour to listen to their music in the wind or for a lovers’ tryst. Their daughter was probably also out there, either to spy on her hated step-mother or to find her father. Then there is that gendarme commander who seems to have left footprints in the oddest places. The U-Boat captain was certainly there and readily admits it while denying the murder. Members of the U-Boat crew may also have been on the lookout to safeguard their investment.

As usual, claims to the Resistance are made both by the Germans to explain away the murder and exonerate the captain and by suspects to hide their guilt. Kohler is indifferent to these claims and St Cyr positively bristles because he has heard this plaint often used to cloak evil. To add to the brew there is at least one Jew hiding in plain sight and a young boy may have stolen the money to bribe passage to England to join De Gaulle. Or he may be dead. The Jew has no chance. The fatalism is endemic.

Around and around Kohler and St Cyr go questioning everyone, being told repeatedly not to question anyone least the morale of the U-Boat crew be undermined or the Resistance revealed. They are threatened, harassed, misled, and lied to. All typical. The U-Boat campaign is interrupted on every clear night by RAF bombing attacks, one of which nearly kills St Cyr, while members of the Resistance are preoccupied with setting differences among themselves with weapons dropped by the British during the distractions of the bombing raids.

The submarine bunkers remain in tact despite the RAF bombings.

The submarine bunkers remain in tact despite the RAF bombings.

The well known fatality rate of U-Boats is sufficient to erode morale, and the Resistance is conspicuous by its absence in the tightly controlled area around the ports. Submarine connoisseurs will realise this is the area where ‘Das Boot’ opens.

Hardened kriminologist will have no trouble spotting the villain early on, but the interest in these stories is the trip, not the arrival. Lorient is a closed military zone rather like an island and its denizens know each other well, German and French. Kohler and St Cyr peel away the layers of lies, deceptions, half-truths to arrive at a conclusion or sorts. On the one hand it is a formulaic police procedure but on the other it is a study of humanity in such inhuman circumstances. The atmosphere that Janes draws is the chief interest to this reader.

Food is scarce, fuel nonexistent, warmth but a memory, tobacco beyond price, exhaustion general, rather than fear most people, German sailors or French civilians, are numb and weary. Yet the nightmare goes on and on.

The crew of the captain’s U-Boat have no desire to return to the depths, fearing they cannot beat the odds again, but if they must to back to sea, they certainly want the dollmaker at the helm and not a new officer, ergo he cannot go the slammer even if he killed the shopkeeper.

Before becoming a full-time writer, Janes taught high school mathematics.