Moustaches, butter chicken, cricket, Pakistan, history, international intrigue, terrorism, samosas, this caper has it all!

India’s greatest PI is once again on the job. That is PI as in Private Investigator not as in Principle Investigator. Vish Puri by name, he lives in Delhi but in this outing his travels include Mumbai and…. Pakistan! Gasp! It is further away and more alien than Mars, New Jersey, or Indian take away in Ballarat!

While at a banquet after an Indian Super League cricket match in which his nephew played, Vish is there when a visiting Pakistani falls dead, face down in a dish of butter chicken. Holy samosas! Vish had earlier espied this Paki skulking about in the garden, though he did admit that all Pakistanis skulk as far as he is concerned. This dramatic death throws Vish off the current case of the moustache-napper. There are contenders for the title of the longest moustache in India and they are being shaved in their sleep! The mo disappears and a clean lip remains. Nothing is sacred in secular India!

His team consists of Tubelight, Handbreak, Facecream, and assorted others contracted in when needed. Back in the office Madame coordinates. It is a smooth operation, usually, mostly, sometimes. He meets contacts around Delhi in air conditioned ATM lounges (cages), those glassed in ones, where he sticks up a ‘Closed’ sign to deter others while in conference. No tricks are missed.

Along the way, much Indian cuisine is consumed, and why not. He has stuck a dowel in the bathroom scales so his weight remains constant when Madame checks him, which is all too frequently.

The plot thickens with international gamblers, Scotland Yard detectives, a digital gecko, and more. It become necessary for Vish to travel to Pakistan! He spends some time trying to avoid it, but in the end, applies for a visa, and after more delay crosses the border, where he expects to be murdered immediately. He is astonished to find he is treated civilly and respectfully. In the end what drove him to go was not the case but the chance at tasting a delicacy in Lahore. This is not the cesspit of violence and corruption he had expected.

There is much about the terrible days of the Partition, enough to put anyone off religion as Muslims hacked up Hindis who happily reciprocated.

An unknown story to me.

An unknown story to me.

The sins of fathers and mothers live on.

In fact the murder was part of the long fall-out of those dark days. Much to his surprise Vish finds several Pakistanis who are stalwart and amiable, and they share information. But he also discovers that his Mummy, who has long had a penchant for interfering in his investigations, much to his annoyance, has a deep and dark past. In fact, she was a secret agent for the Indian Rescue and Recovery Commission during Partition and went on many dangerous missions, as one of his new Pakistani associates tells him with admiration. ‘Mummy!’ Vish cannot believe it but somehow it fits. Not a word has she ever spoken of those days.

Together they crack the case of the murder and also the international gambling, while the team finds the mo-napper.

Much of the subject is serious, but the touch is light, and while the history is detailed, it is crucial to the plot and focussed, as well as informative. I also found enlightening Vish’s defence of India as a society compared to Pakistan and its generals. India may have corruption and incompetence galore but it has never resorted to the rule of the gun. Another a good show.

Category: Book Review

‘The Mummy’s Quest’ (2017) by Robin Bailes

This novel is a tribute to Universal Studio’s ‘The Mummy’ (1932) which spawned continual imitations, successors, parodies, and mutations. There have been so many successors that they have nearly obscured the fount. The original, by the by, is moody, understated, and terse, whereas most of the spawn are bland, bloated, and blurred.

It starts with a museum of antiquities in Cambridge (England) among myopic bookworms and nerds, along with some shadowy figures who turn to kidnapping when Google Translate fails, and a dark prince. In addition, far away there is a newly discovered and untouched tomb in the Egyptian desert. With these ingredients the ride should be fun! It is a mile a minute once the big gong sounds!

The prize Mummy in the Cambridge Museum breaks out of the glass case that has held its 4000 year old remains. Gulp! He staggers around with an ancient hangover. Woe to anyone who gets in his way. Careful, all ye who look upon Mummy!

Soon the Brotherhood of Wannabe Villains appears to assist Mummy, while the Librarians rally to oppose them. Caught between are assorted Gypo nerds. There is a demonic cat. Feline situation normal.

The cast assembles in the desert where they find the requisite dusty diggers under the direction of Maggie, a fiery site manager, who scares the Mummy. In a straight-up no-holds-barred fight Maggie against the Mummy, the fraternity brothers bet on the Mags, but then changing the odds, the evil queen-pharaoh is reanimated for the showdown in a gore feast. Bad! Good! Turns out, at the moment of truth it was the wrong Mummy! How’s that for a plot twist. It is so hard for evil queens to hire good help for an eternity. Incantations, EEO, hexes, KPIs, mesmerism, spells, LSAT, GPS, minimum wage; nothing is enough!

There are flash backs to the Lost Dynasty Egypt to explain the shrouded players: the priest, the pharaoh-queen, the rebel, and…[was there a cat?]. These seem to go on a little but it is all relevant at the end.

The prose is expository, no flourishes, no elevation, no psychological depth, no big words, but well paced. The characters are differentiated in manner and speech. It reads like a film script to some extent, a comment that would please the author, I expect.

I came across Robin Bailes’s ‘Dark Corners’ movie reviews on You Tube by accident but once I found them, they became addictive. The man has a razor tongue and a mastery of the form with few equals. His five-minute reviews are informative, amusing, insightful, and devastating. Other reviewers on You Tube are, by comparison, self-indulgent, verbose, unfocused, and boring. Better yet, I lodged a suggestion for a film to review and he replied, and later screened the review acknowledging my suggestion. That feedback loop worked, a rarity that.

I signed on as a You Tube follower, became a regular hit at his web site, donated to his cause at Paetreon, and now bought this, his first novel, does all of this make me a Bailesee?

‘Solaris’ (1961) by Stanislaw Lem

Deep space travel is routine and many planets have been surveyed. There was nothing of interest about the planet Solaris and so it was ignored for years. An astronomer then noted that its orbit was odd. Because it circles a double star, one red and the other blue, its orbit should be erratic but it does not confirm to the laws of physics. (The same is often said of the fraternity brothers.)

Solaris receives closer inspection. It is nearly completely covered by an ocean with only a few rocky outcrops like a few tufts of hair on a bald man’s head. Landing parties use those but cannot find anything relevant, but they do see that the ocean’s motion is varied and unexpected. Again they wonder about the laws of physics. After years of study, the field of Solaristics concludes there is an intelligence in the ocean regulating the orbit by some means. The book is replete with a gentle satire about academic specialisation as an end-in-itself.

More studies fatten cvs and efforts to stimulate communication are made using radio waves, ion streams, pictures of Mother Teresa, neutrino bombardments, pamphlets, and an unauthorised use of intense x-rays and other more destructive means to no avail. Solaris seems immutable like reasoning with a Republican.

A research station is placed in orbit to observe with a crew of three on a three-year stint and has been there for years. Then the one day commander of this station a the time requests base to send a psychologist. Isolation in space does lead to mental problems so shrink Kris Kelvin is dispatched. The novel opens with his arrival and the preceding information emerges piecemeal.

No one greets him. Odd. No one seems to be about. Odd. Moreover, there is disorder everywhere. This is no way to run a space station! He finally finds one of the scientists cowering behind a barricaded door. The other scientist will not leave his lab and speak to Kris. The plot thickens.

The commander who asked for the visit committed suicide that very morning. Odd! What to do? Kelvin decides to examine the corpse in the best tradition of the police procedural. En route he hears barefoot steps and passes a large black woman in tribal dress. She blankly ignores him. He is astounded. That is only the beginning.

Cutting to the case, each member of the crew has a spectral guest. It is someone a memory of whom is found deeply etched in his psyche. This is not necessary someone he wants, but it is the deepest, most ingrained memory. In Kelvin’s case his guest is Harey, a girlfriend who also committed suicide, so that he feels guilt, regret, and remorse.

These guests, the crew concludes, are from the Solaris ocean which is engaged in a Communicate with the Humans Project of its own. The Solaris guests have assumed the identities they have because of the importance of the memories to each scientist. Once embodied the guest seems to know a lot but have no memories of specifics. Harey is sweet and clingy but has no idea how she came to be there, but strangely she knows things about Kelvin that occurred after her own death. Evidently to some extent the guest can tap the host’s mind. But the commander’s guest has remained after his death! Talk about overstaying a welcome!

Various methods are tried to analyse the guests and to eject them from the station but they keep coming back. Meanwhile, Kelvin finds it easy to have Harey around. They engage in many conversations as she becomes aware that she is some kind of aberration, clone, replicant, or dream.

She is a virtual reality girlfriend. She is self-conscious, intelligent, capable of learning but she can never be more than Kelvin’s memories of her. In that way she is limited, and realising all of this she grows despondent. Of course the fraternity brothers wanted to know whether she is full functional but that is not made explicit.

There are many conversations with one of the scientists about the ocean, god, creation, Amex bills, morality, metaphysics, ontology, bratwurst, on and on. It is talky. We never find out about the other guests, nor is there any contact with the ocean. It is all trip and no arrival.

Is the omnipresent but uncommunicative behemoth of the ocean of Solars a metaphor for…. Soviet Communism viewed from the observation platform of Poland? Or just a yarn?

It is a meticulously written and original work to read it today, let alone more than fifty years ago. I sat through the Soviet 1972 film version years ago without it making any impression on me apart from the cruel and unusual length of three turgid hours.

The Grand Jury at Cannes is made of stronger stuff than am I.

The Grand Jury at Cannes is made of stronger stuff than am I.

But in the age CGI Über Alles I expect it will have to be done again one day. No, I have not seen the Yankee 2002 version either, well, except for some scenes that I came across somewhere.

Channel flipping, no doubt.

‘The Stars, My Destination’ (1956) by Alfred Bester

A bildungsroman of sorts as Gully Foyle grows and changes with his experiences, and the greatest changes occur at the instruction of women. The first is the one-way telepathic black woman whom he rapes and, in a way, sets free. Later they form a team of convenience. The second is Jiz whose influence on him is considerable, making him grow and change. Finally is the White Icicle who attracts and repels him in equal measure. Least influential but last is Moira, the stay at home.

Gully begins the story as an uneducated barely verbal spaceship hand on the Nomad. Think of the channel 7Mate demographic without the drooling and scratching and you have him. By the end he is richer than all the cynics who own Channel 7Mate put together.

The Nomad is a wreck floating in space and Gully alone has survived the attack by dumb luck and a resourcefulness he did not know he had. A friendly spaceship hoves into view and he signals it, quickly and repeatedly. Yet it passes him by, contrary to all the laws, rules, norms, and ethics of spaceflight.

Thereafter he swears revenge on that ship. Driven by that desire he survives, and later prospers, and learns, and seeks the guilty ship. The adventures are many, the plot twists are deft, the characters differentiated, the settings detailed and followed through, and the science fiction is etched into the story and the characters.

The first, and as it turns out, the last key, to the narrative is that in this world of 2550 teleportation is as common as walking is today. To move from one place to another one teleports oneself, clothes included and anything one is carrying or holding. Distance varies with ability and practice. It is safer than walking since there are no crazed drivers on King Street to dodge. The method is a mental discipline developed by a Mr. Jaunte, and so it is ‘to jaunte.’ The telekinesis involved is crucial to the narrative and the denouement.

There are three treasures in this quest. First is a vast fortune of Credits 20 billion, where a hundred credits is a great deal of money. Second is a rare mineral that releases vast quantities of energy, far exceeding uranium and its mutant cousins. Third is Foyle himself, much to his own surprise, and to the reader, too.

There is much satire of the super rich, so much it grew tedious to read, but it is fitted to the overall plot like a jewel in a ring. In a world where movement is by thought conspicuous consumption to signal one’s riches becomes conspicuous transportation.

Nicely embedded in that satire is Foyle’s hiding in plain sight for a part of the time, as the most ostentatious and conspicuous transportee, while he seeks leads to the hated ship. Although his choice of an alias was a quick and certain give away it took the villains a long time to figure it out.

There are also a couple of surprising passages for a 1956 publication about the role of women in this wealthy society, sequestered, hidden, and rather like pets in a zoo. None of that applies to the first three women whom he encounters, though the last one is of that sort of society. Finally he returns to Moria as we all do. One is an illegal immigrant and the second a convict.

Without any explicit comment, Bester also shows a society with deep, very deep class divisions so that members of the working class where Foyle started, are barely educated, civilised just enough to do a job like living machines. Indeed he is so dense that at first the target for his vengeance is the spaceship itself. Only later does understand that the crew made the decision and then he targets them, but in time the realises that the captain gave the order.

There is no preaching by the author but the reader gets that point. So much Sy Fy is spoiled by childish preaching by the author using the keyboard as if it were a sledgehammer to drive points home to the dense reader all too much like the morons on Fox News yelling at the camera.

Alfred Bester

Alfred Bester

Another flaw that has stopped me reading a few Sy Fy titles is the ostentatious erudition that some author parade to show how clever they are, like the pointless CGI of so many movies, but which advances neither plot nor character. This title is free of that egomania.

That it opens with an excerpt from William Blake’s most famous poem which is integrated into both plot and character.

I read it in an adolescent Sy Fy phase but had forgotten all the details.

By the by, holding physical objects accountable for the consequences arising from them may seem absurd to us — we know the spaceship itself did nothing — but Athenians did not. A building block that fell and killed some would be tried, sentenced, and smashed.

‘The Invincible’ (1964)

The spaceship Invincible with its formidable array of technologies and a very experienced crew of space explorers arrives at Regis III to find its sister ship Condor which landed there two years before and has since failed to report.

Great precautions are taken. Force fields and robots are deployed. There is a lot of science in the text about these machines and their programs. The crew numbers about eighty. They find Condor and most of its like-numbered crew are dead. Despite full larders on the ship the doctors are sure most of the Condor’s crew starved to death. Very strange. Was it one of those fad diets!

There are no signs of life on the inhospitable planet. If Condor had surveyed it and left, the planet would probably not have been bothered again since there seems to be nothing there of interest or use and there are so many other worlds to visit.

But now there is a mystery to solve. What happened to the Condor’s crew? Exploration occurs. Speculation is riff. The scientists compete in boring each other to death with wild hypotheses.

Then some of their crew go off the air. They are present in the flesh but seem unconscious though wide awake. Think of a Republican congressman and there it is. Mouth open but brain off. This happened to more of them every time that black cloud is around. The black cloud is around more and more.

The black cloud is in fact comprised of a myriad of tiny, fly-sized, microbots evolved from some alien technology of a race long since dead, say two million years ago. The bots surround one’s head and that net burns out the electricity in the brain and makes one into a slavering idiot incapable of anything, eating, drinking, hailing a bus; the victims are only able to vote for Australian idol.

They try to fight the bots with the Invincible’s mighty array of weapons, blowing up a good part of the planet but not landing a punch on these micro-terrorists. Sounds like the foreign policy of some stupor power does it not?

In the end the Captain finally capitulates and decides to blast off, but first the crew has to be accounted for. One principle of space flight, says the Captain, is that no one is left behind alive by mistake or purpose.

Since no Republicans were handy, they hit on putting colanders and tin foil on their heads to hide their brain activity, and set about retrieving their dead and missing. This method works per innumerable Sy Fy movies.

Off they go.

Stanislav Lem wrote reams of Sy Fy, including the novel on which is based the movie ‘Der Schweigende Stern’ (1960) reviewed elsewhere on this blog, though his novel lacks the propaganda inserted into the movie, which insertion led Lem to withdrawing from the production per the official web site of Stanislav Lem.

The initial mystery is intriguing and the description of the apparatus of the Invincible is detailed but mostly superfluous to the plot, story, and characterisations. After such a detailed and long built up the climax seems a squib.

‘Nemesis’ (2014) by Jon Martin

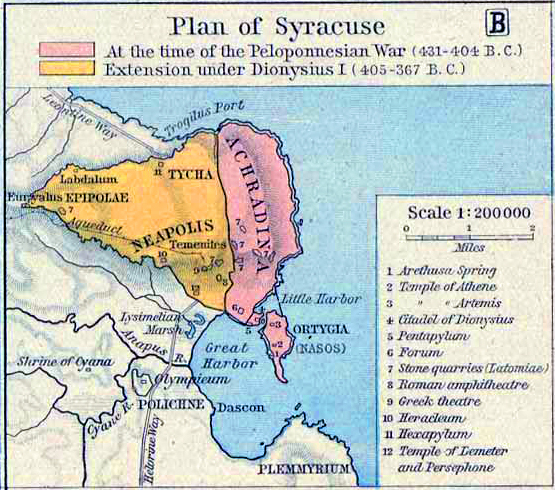

A superb novel that traces the early life and career of the Spartan Gylippus of the Fifth Century BC. He was a major figure in the Peloponnesian War and the spine of the novel is derived from Thucydides’s ‘History’ of that war.

There is much insight into the inner workings of Sparta. The author knows the detail well but wears the learning lightly, though making no concessions to readers by spelling everything out. The reader is left to figure it out when Greek terms are used or to refer to the glossary at the end.

The divisions in Sparta are well realised. There are personal and clan rivalries and also personal ambition. As one character says much later to Gylippus from the outside the Spartans appear as one man. Hardly. The author makes the Spartans all too human, at times vain, myopic, venal, ambitious, resentful. But those tensions are played out behind many curtains.

Athenians are no better and their fractious conflicts are largely played out in the open air.

The contrast to Gylippus is the Athenian Nikias, another giant from the pages of Thucydides. Nikias does all in his considerable power to avoid war, and rejects command twice when it is thrust on him, and yet he dies in the war on duty,

Readers of Thucydides will know that the crucible for both Gylippus and Nikias was the Athenian invasion of Sicily. The arc of the story begins with the Athenian reduction, pillage, and rape of Melos, where the cry ‘The Athenians are coming!’ anticipated the German cry ‘The Russians are coming!’ in 1945.

That was Athenian democracy at work. The opening scene of the Athenian slaughter of chained Melian prisoners and then forcing the surviving women to stack the bodies of their faheres, husbands, sons, and burn them are gruesome indeed. After that the rape begins, followed by a slave market. Two young girls escape, and though that was unlikely, as a plot device it takes them to Sicily for later events.

We went to Melos in 2007 as homage to this atrocity.

On a pretext Athens invaded Sicily to seize the island and its agricultural wealth now that the Persians have closed the Egyptian grain trade. The expedition was gigantic and command was divided and proved contradictory, aggressive in one instance, and passive in another. Nikias searched for a political solution to accommodate the appetite of the demos on the Pnyx in Athens, while the other generals wanted a battle in which to be a hero. There is no pretence at unity among the Athenians.

Melos had appealed to Sparta for help in deterring the Athenians, but Sparta did not act.

In Sicily the democratic city of Syracuse likewise appealed to Sparta, and Sparta sent one man, and that was enough. ‘Throughout time allies did not sent to Sparta for ships, or money, or soldiers, but for one man,’ said Plutarch.

The divisions within Syracuse are well realised, and full of the irony of reality. The staunch defenders of democratic Syracuse’s independence are the oligarchs, while the Syracusean democrats sell out to the invading Athenians at every opportunity. They do so not for ideological reasons but because they hate the oligarchs.

The Athenians expect a show of force will bring Syracuse to its collective knees, and are mildly surprised by the resistance, but they remain confident that Sparta will not act. Though Nikias is less confident about this than his associates. Indeed he is so very cautious that he does not want to risk a battle for the gods can be fickle and his army is a long way from home, so he set about winning local allies on the island, establishing a supply base and so on. Time passes with small skirmishes.

Then comes Gylippus. There is a marvellous scene where the Athenians are marching around the walls of Syracuse in a demonstration of shock and awe when they encounter in a field a battle-line of hoplites standing at rest. The raw Syracuseans do not stand easy. When they lined up for a battle earlier, they fidgeted, wavered, squirmed, twisted, turned, and all but ran long before the fighting started. Not so on this day. The line is firm.

The Athenian force is great and this opposing line is much less and it is near the end of the daylight. Yet these hoplites stand calm and relaxed with their shield turned side ways to the Athenians. The Athenians approach and then on command the hoplites turn the shields faces catching the last rays of the setting sun to the Athenians who then see the lambda on the shields for Laconia, or Sparta.

The shield is big enough for a man to hide behind it when the arrows fly. Together with body armour from toe to head the load on a hoplite was about thirty kilograms in battle.

The shield is big enough for a man to hide behind it when the arrows fly. Together with body armour from toe to head the load on a hoplite was about thirty kilograms in battle.

The Sparta have, this time, come, about a thousand of them face this Athenian contingent of perhaps five times that number. The frisson through the Athenian ranks is electric. Spartans! Darkness falls and no battle is joined but the news travels fast and by sunset everyone knows the Spartans have come.

Game on. Over the next three years there is much cat-and-mouse between the protagonists, each undermined by rivals there and back home. Both Nikias and Gylippus have a two-front war, one military the other is a double political one with their respective home cities and local allies.

While Gylippus did not come quite alone, he came with only a token force compared to the forty thousand in the Athenian expedition. He relied on the defensive walls of the city and concentrated on cutting Athenians supply lines and stealing silver from them so they could pay the mercenaries that comprised the bulk of their forces.

Nikias was often infirm but he was not permitted by the demos to resign and he dared not leave on his own initiative for the demos had more than one unsuccessful general put to death, sometimes along with a few relatives to drive the point home. Likewise Gylippus, frustrated as he is by his reluctant allies in Syracuse, cannot go home without a victory.

The use Hermocrates makes of the two escapees from Melos is cleverly done by the writer. The exposition of the divisions within Syracuse are well set out though the Athenian sympathisers are largely cardboard. The author leaves aside the larger question that confuses modern readers, how could democratic Athens attack democratic Syracuse. The answer is, of course, that Athens by this time would eat anything. Even as this expedition was launched there was talk of Carthage, then but a legend.

The writer’s wit, insight, sympathy for the principal characters and the way he interprets the facts recorded by Thucydides is wonderful.

Jon Martin

Jon Martin

Clearly he has walked over all the ground he describes and done so with a sponge in his mind soaking it all up. I read his ‘Shades of Artemis’ (2004) about Brasidas some years ago and found it fine, too.

Gervase Phinn, ‘Head over Heels in the Dales’ (2000)

Third in a series of novels about life in the Yorkshire Dales of England: Low key, rural, disarming, and downright charming. The eponymous hero is one Gervase Phinn, school inspector. Some will remember these (in)spectors who were often the object of fear and trembling.

Gervase is one of a team of four inspectors presided over by a senior inspector assisted by a secretary. This unit in turn reports to head office at the county. They are employed by the county but work to rules set by the Ministry of Education in distant London. Whatever the organisational chart, they are a small unit within a large organisation, combing the best and worst of each kind of organisation.

The master narrative is Phinn’s life and career. In this entry it is his second year on the job and in these pages he gets married to Christine and they set up house in a ‘builder’s delight’ of a cottage on the Dales, which are lovingly described.

Think of the countryside of ‘All Creatures Great and Small.’ Their efforts to make the cottage habitable are monitored by a neighbour who makes many observations, all of them laconic and most of them ironic, careful always never to lift a finger to help.

At work Phinn visits schools, sits in classrooms, talks to children, and attends one speech day after another. He also participates in staff development exercises at a training centre. The bulk of the novel strings together such episodes, many of which are delightful, as when a five year old girl in a class asks him how to spell ‘sex.’ No spoiler.

At Christmas he sits through four nativity plays in schools as he delivers the end of year reports. Dreary it may sound. Repetitive it may seem. But in the telling it is neither. The four plays are done in different ways, and Phinn, the writer, has the eye and ear for detecting those differences and conveying them to the reader. Wonderful.

At work the senior inspector and head of the unit, Harold, announces that he will take very early retirement in a few months, meanwhile a successor is appointed. In due course a much credentialed new senior inspector is named. Prior to taking up the job he pays several visits to the unit and the county office.

He speaks but McKinsey and talks but key performance indicators.

He bristles with changes and more change, and further change. Everything must change from the colour of ink in the reports to the number of rings of the telephone before answering. Everything must change from the time spent on task to the numerical indicators harvested from audits. Bullet points must replace text and text must replace bullet points. He is a very image of the modern major manager. As much as he is caricature he is also reality. In his hours of consultation, where he does all the talking, he never mentions children, teachers, schools, learning, or education. But the generic McKinsey-speak rolls on, and on. [Pause.]

Each of the members of the unit reacts to him. The Irish woman, Geraldine, is the first to realise the news is bad. Later when they catch on, David and Sidney are stunned into silence, an unusual state for either. Julie, the office secretary starts looking for another job. When this McKinsey clone refers to Connie at the training centre as the janitor, she …. and gets her revenge. She is the building supervisor! And proud of it!

The cast of characters is an amusing lot and given plenty of page time in the manner of all those character actors that enliven Frank Capra movies.

Lest it all seem light as air, note that there are serious moments. When David, with his usual insensitivity makes a stupid, sexist joke concerning unwed teenage mothers, both Geraldine and Connie set him straight in a one-two punch combination.

More than once Phinn is confronted by the conundrum of means and ends. The Ministry requires teachers to keep a tidy classroom, plan every teaching activity two weeks in advance, make written records of each class meeting, involve students in activities in prescribed ways, improve students language use and written expression in measured steps, and so on. This is the administrative approach to teaching much favoured by administrators and ostensibly it is the means to the end of education. Most teachers comply and most are adequate, and nothing more. Consider that approach applied to gardening for a moment to see it weakness. The plants are growing all the time in unplanned ways right now, not two weeks from now. A neat and well organised gardner may nonetheless have a dead garden.

But Gervase encounters in these pages two extraordinary exceptions. The first has a chaotic classroom in which the children do most of the talking as they explain things to each other. The room is untidy. Extremely! There is no plan. But there is excitement, curiosity, focus, learning, engagement, interaction, experimentation, argument, and more which the teacher seems to manage with hints and materials. It is all palpable but ineffable on the pages of the pro forma of the report Phinn must complete. Which is the priority? The Ministry standards or the children’s learning, because they are certainly learning, of that he has no doubt. Hmmm. Of the second deviant teacher there will be more in a moment.

Drafted to speak to a ladies’ club. He meets the president at her home where she orders her husband, Winco she calls him, to and fro like a wind-up toy. She blusters and demands and Winco complies with an amiable ‘Righto’ on each occasion. Phinn finds them both pathetic.

Only later does Phinn realise the Winco has every medal the RAF bestows, Distinguished Service Cross, Battle of Britain Ace, George Cross, two Life Saving ribbons, and others and that ‘Winco’ is short for ‘Wing Commander.’ Still later he learns that this woman was a Air Raid Warden with her own set of medals for pulling people from burning buildings while delivering babies in the rubble with the other hand. Never judge a book by its cover contra Bill Byson who never does anything else.

Gervase visits a Church of England school where all the most delinquent and troublesome students are sent within the high walls around it. Most of the teachers are rugby players. Most go through the motions with the sub-verbal, primeval slime they see as their students but are well organised with pristine paperwork. Phinn is shadowing one such amoeba who surprises him by her anticipation for the last class of the day, Religion. Huh? Well, he is not sure. She does not seem the sort to be ironic, but she is also difficult to understand mumbling through lip and tongue studs with a thick accent and three-word vocabulary.

Lo and behold! These students who have been indifferent and hostile in every other class that day, are completely rapt in Religion. The instructor goes at the Bible as though it were a football game, narrating the stories and eliciting reactions from the bleachers, and react they do! With four-letter words unusable for a family blog like this. Pontius Pilate gets a right barracking! At the end, they file out arguing about their reactions of events just unfolded. Engaged they are! Learning they have been, but how to square that with the Ministry pro forma? That is the question.

Gervase Phinn

Gervase Phinn

The book ends with a school fete and a verse reciting contest which Phinn must judge. His previous experiences at judging were none to happy. However deservingly obvious is the winner, the others have parents with a great deal to say. It is climatic, and great fun.

Future Man versus the Man from Lisbon

Future Man won!

‘The Man from Lisbon’ (1978) by Thomas Gifford was homework for our 2018 Iberian excursion. It chronicles the escapades of Reis who lies his way into an engineering job in Angola in 1915. Africa seemed better than the Western Front. I got it from Audible, about which more below.

From humble origins, his father a mortician, Reis strives to better himself. But to get started he needs an angle in the stultified society of Portugal and this he procures by faking a degree from Qxford University in engineering. There will be few Oxonians in Angola, he reasons, and he will not be challenged. He does have some technical school training in mechanics so off he goes, diploma in hand, with his adoring wife and faithful sidekick in tow for Africa.

His forgery is nothing more elaborate than some expensive paper on which he writes out a diploma for himself. That ought fool ‘em! It does.

The little he knows together with the willingness to do the hard work himself lead to success in Angola. Soon he is doing two full time jobs as director of public works for the colony and director of the Angola railroad company with ease and raking in the escudos. While other engineers think the railway bridges will fail under the weight of the new engines he has imported, Reis is confident they will not. It is a confidence based on nothing. Damn those pesky stress tables! Even the laws of physics yield to his will power! Miraculously they do. It seems those stress tables were fake news avant le mot.

He returns to Lisbon loaded with dosh but blows his fortune on the vanities of automobiles, luxury fittings in his home and office, speculative investments that come to nothing. Getting desperate. he tries yet another bold swindle and this time the stress tables are right and he goes to the slammer in Oporto! I stopped at this point because I did not care about his fate, though I see on Good Reads some were gripped. It runs to be in all more than 21 hours. Agony without ecstasy.

Of passing interest was the account of early twentieth century Angola and its myriad natural riches. The colonials are sun-stunned alcoholics for the most part and the natives all but absent. Reis’s basic knowledge of mechanics sufficed, together with his readiness to get his hands dirty by doing the work himself, for his early successes, and also set him apart socially. The few other engineers in Luanda supervised natives who did the dirty work, but Reis did it himself, and got it done in record time and with good effect. These successes of course angered the others.

The references to World War I ring true because Portugal did join the Allies and suffered for it. But scant are these references. The Portuguese division on the Western Front was obliterated in a single day in an offensive. Its replacements met the same fate later. The survivors brought home Spanish flu.

The prose has many nice images. This Iowan Gifford could write, if only he had something to say.

Thomas Gifford

Thomas Gifford

But my disbelief did not remain suspended. How could that hand written fake Oxford degree in Portuguese fool anyone? Second that will power prevails over stress tables, i.e., the laws of physics. But most of all, there was nothing about Reis of interest, a superficial egoist. So what, a dime a dozen they are.

The narration is by a Portuguese speaker who handles the proper and places nicely while mangling the English. Possessives invariable are said as ‘es’ and extra letters creep in elsewhere, too, e.g., ‘dastardsly’ and more. This became predictable and distracting. Twenty hours of this narration would be enough to put me off going to Lisbon in 2018 and so I took no chances.

However it was the inanity of the narrative that exhausted my good will. Thomas Mann’s ‘Felix Krull’ was the confessions of a confidence man (like Reis) whose career revealed the venal and moral corruption of post World War I Germany, told with wit, insight, grace, and rueful good humour. It dissected events and individuals with a scalpel. Not so here, where soft focus prevails. Me, I kept hoping the jerk, Reis, would get his comeuppance, and the sooner the better. I left him stewing in the Oporto slammer.

In contrast Captain Future together with his Futuremen in ‘Worlds to Come’ by Edmond Hamilton (aka Brett Sterling) from Radio Archives has to save the universe from a shape-shifting critter out of the sixth dimension! That narrative had purpose AND drive! This, too, was from Audible.

Loved the death rays, atom pistols, proton canons, and other NRA boy-toys. Then there is the robot assistant who took itself apart to pass through a small hole in a wall and reassembled himself on the other side. That reminded of something I tried once without success near a girls’ dorm. The deathless brain floating around in a plastic box caused me to re-examine some of the leftovers in the refrigerator Tupperware. Yuk! Is that the fate for professors emeritii, I had to ask?

Of the moon pets the less said, the better. I am not picking up after them! And that is final.

The scientific explanations of the hijinks was pulp fiction which where it all began (1940-1951) and so suitable for a climate change denying anti-vaxxers. While I turned off ‘The Man from Lisbon’ I could not turn off ‘Future Man’ and I will go back for another episode of exploits, there being at least another fifteen! Whopee!

Ed Hamilton

Ed Hamilton

There is a ponderous entry on Wikipedia about ‘Future Man’ that almost destroys the pleasure in it. It has all the appurtenances of Cultural Studies. (I always fear the worst when I hear the phrase ‘Cultural Studies’ and it has never let me down. The worst follows that term as the night, the day. It is an even more reliable indicator of nonsense than ‘Post-Modern(ism.’)

I acquired both books from Audible, whose customer service is superb. I reported a problem in downloading these titles on the web page and got a phone call within the hour walking me through the correction. This was followed by an email setting it out in writing for future reference. Many profuse thanks. Of course, the problem was obvious once I realised it. Doh!

My listening is done on solitary dog walks while Majic sniffs the trees on nights when the diva is rehearsing or performing, or mornings when I am at the gym where I passed a hundred visits on the current annual membership as I have each of the retirement years to date.

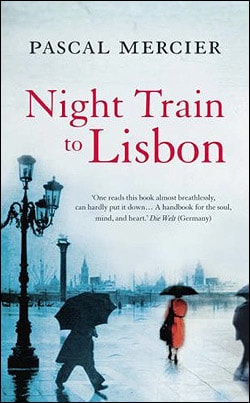

‘Night Train to Lisbon’ (2008) by Paul Mercier

Raimund Gregorius, known as Mundus, teaches dead languages to gymnasium students in contemporary Berne, Switzerland. He eats and drinks dictionaries of ancient Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, barely noticing when his wife leaves him. His only topics of conversation is the ablative case in Latin, declensions in Hebrew, and inflections in demotic Greek. He can bring boredom to any dinner table and so is invited to few, well, none.

Think Immanuel Kant, Mundus is a man of unvarying routine, a routine not interrupted by the aforementioned wife’s departure. Every morning at 8:15 a.m. he walks across a bridge to the school, where students and staff are silently agog at his myopic intensity. This he has been doing for thirty plus years for he is now fifty-seven.

In the rain, with wind inverting his umbrella, he trudges to school with a brief case full of marked essays to return to students whose every error, great and small, has been meticulously annotated, and he has prepared a lecture on the main themes in their work, mostly about their errors, which lecture he calls to mind as he wrestles the umbrella.

Losing the battle with the wind, he sees ahead a woman in a red coat, standing next to the bridge rail in the rain staring at a piece of paper. (Immediately I saw Irene Papas in the rain from ‘Zorba the Greek.’) The rain continues and the paper is sodden. Is she going to jump off the bridge into the gorge? He quickens his step; as he approaches he can see the ink running on the page. He looms up and she is startled out of her reverie and in reaction he drops his brief case spilling out the essays. In the ensuing confusion he takes her to a coffee shop across the bridge to regain composure. Even before getting away from the rain she extracts a piece of paper from him and writes down a telephone number, which in the coffee shop is copied again on a dry piece of paper, while Mundus sweeps the sodden copy along with escaping essays into his brief case. She keeps the telephone number once it has been transcribed.

They speak French and he discovers that she is Portuguese. He takes her along to the school where she can dry out in one of the women’s cloak rooms. He is thus late for his class; moreover the janitor is stunned to see Mundus late AND in the company of this woman, dripping on the just mopped floor. She goes off to dry, and with a word of thanks leaves. Enigmatic.

He goes to the classroom and thinks about what he has just seen, and done. He did not ask her the obvious questions. What were you doing standing there on the bridge. What is so important about that telephone number? Who are you? What is a Portuguese doing in Berne? He has spent his life not taking an interest in others and does not start now. Yet he cannot let it go.

As he hands back the essays, he notices the wet paper with the telephone number on it. (The pedant in me wondered how he could tell it was a telephone number, and not an account number, or social insurance number, a series of soccer scores, or…. ) He stumbles through the morning double class, quite uncharacteristically letting errors go unmentioned, and then goes to lunch. Ah, the life of the scholar.

This man is a loner and seldom mixes with others. On that score he has reverted to routine. He sits in another café letting the food and drink he ordered get cold: Portuguese, a Romance language derived from Latin, but that is all he knows. Instead of eating he goes to a bookstore that specialises in languages and finds Portuguese books. As a scholar he relates to books. He does not look for Fado music, or a Portuguese restaurant, or DVD of Lisbon travelogue. Bored on a rainy day and in awe of Mundus, of whom he knows, the store owner, who just happens to know Portuguese, reads some passages to him from a book of reflections, the substance of which reminded this reader of Michel Montaigne’s musing on life. Mundus likes both the sound of the spoken Portuguese and the musings which owner translates for him. He buys the book, along with a Portuguese dictionary and grammar and goes home, blowing off his afternoon class. This is the first class he has ever missed.

Overnight he begins to learn Portuguese. That may sound impossible but Ekkehard with whom once I shared an office in the Netherlands was a linguist who soaked up a language like a sponge. After a few days in the Netherlands he was speaking Dutch. Mundus finds the train connections to Lisbon by telephone (no internet for him) while dodging inquirers from the school come to look for him at the door and on the telephone, and he sneaks out of his apartment to go to Lisbon! By train. At night.

He has that telephone number. He has that book of musings. But why is he going? He asks himself that very questions more than once. He does hesitate but on he goes.

The local takes him to Geneva, where he changes trains for Paris, where he will change again for Irún in Spain and then on to Lisbon. While he rides he reflects on what he has left behind, a routine set in concrete that contains within its walls more sub-routines, and nothing at all, a series of nested do-loops that lead nowhere.

A European train station at night.

A European train station at night.

Mundus’s recollections of academic conferences, seemed familiar. All those people trying to prove (to themselves as well as each other) how smart they are. Yes, the one-up-man-ship is eternal, phrased ever so politely and usually by reference to some obscure secondary source from a foreign language. Who needs primary sources, after all. But also all those smart people for whom the subject is simply a commodity, today it is Louis Althusser and tomorrow it will be Michel Foucault, and then Jacques Derrida, with no inner feeling for or commitment to the subject matter, despite the ritualistic mouthing these days about passion. The passion is always about the ego, the self, not the subject. Though such poseurs would be the first to decry universities advertising degrees like products, they themselves approach their subject in the same detached way.

Mundus nails many academic pretensions on show in any seminar or conference.

– the high-flown gibberish that means nothing outside the classroom and very little within it

– French notions introduced as seasoning not substance, and unnecessary at that

– study is not fodder for an academic career, it is life itself with colour and melody to which a reader submits but does not conquer

Amen, Brother Mundus.

In Lisbon he begins to investigate the author, Amadeu de Prado. and pieces together his biography. There is detective work here, and the characterisations of the still-grieving sister thirty years later is a masterpiece as also some of the surviving school friends, especially Maria.

Lisbon

Lisbon

Amadeu is Mundus’s alter ego, yet he, too, was a creature of habit. Amadeu lived through the Salazar years and like all Portuguese still bears the marks of those days, good and bad. This is a new world to Mundus as he interviews family, friends, teachers, and others who knew Amadeu, who died years ago of a brain disease. Amadeu’s life is a microcosm of the life in Novo Stato of Salazar in his latter years with the PIDE, the secret police, had a free hand.

In Lisbon he makes no mention of the mysterious telephone number or the woman in red on the bridge who was the catalyst, but only that it seems. Indeed he stops thinking about her altogether and she does not reappear. If she did, I missed it, as explained below.

The musing is beautifully realised. Particularly striking to this scholar was the exchange of letters with the head of the school he left behind. When I mentioned this novel and this episode in particular to a lunch gathering of jaded scholars, there was a respectful silence, which I took to be each imaging the exhilaration that would follow walking away from a yet another pile to essays to mark, yet another pro forma about key performance indicators, yet another research grant application, yet another decanal briefing.

All that and more is true, but it does seem to go on and on for 4 5 8 pages. Mundus wanders through Lisbon, travels to Coimbra, and Finessterre in Spain, following links in Amadu’s life. Then he goes back and forth to Bern and…..THE END.

Like a bad student, doing a reading assignment badly, I kept watching the percentage tick by on the Kindle, ever so slowly. I kept at it because of the jewel like prose, the insights into friends, filial love, comradeship, chance, and so on, but there is no narrative drive. All trip and no arrival.

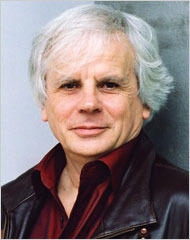

Pascal Mercier.

Pascal Mercier.

The story is very well measured and the prose is exact, and yet a certain mystery remains. The film derived from the novel passed through the Newtown Dendy a few years ago and I was tempted by the prospect of a European travelogue but put off by the prospect of watching Jeremy Irons for two hours. Seeing him always makes me think, and no doubt this is just me, that he has haemorrhoid pain which he manfully bearing, just short of grimace.

The travelogue reminded me of my travels in those parts. I went to Geneva (from Zurich) by train to burrow into the archives of the League of Nations housed there by the United Nations when I was investigating the International Brigades for ‘Fallen Sparrows’ (1994) and then on by train to Neuchâtel to see some Jean-Jacques Rousseau manuscripts, an article based on this study appeared later. To this nerd boy both were thrills. In Geneva I found a 3” x 5” card file prepared by a Greek diplomat in 1939 of individual Brigadiers walking out of Spain to France: name, nationality, age, gender. Nothing much but authentic to the touch. Each soldier an Odysseus and few with an Ithaca to which to return. In Neufchatel I held in my hands, there being no requirement to wear gloves, pages that Rousseau himself had written. He would go on and on for pages after page of quarto, say thirty of them, and then there would be one cross-out, the prose just flowed from his quill in a steady pulse for twenty or thirty pages before it hit a rock. These are nerd-boy thrills.

Moe recently we took a night train from Amsterdam to Prague and back with DeutscheBahn. We did not do much musing. On boarding there were no directions or staff, but everyone with heavy suitcases, narrow corridors, and tiny compartment numbers elbow high. The compartment was a broom closet and the train was boiling — it must have been sitting in the sun for hours. Food was nearly non-existent. But there was worse. The toilet. [Gasp!]

The Man in Seat 61 recommended this service, and said it stopped four times. Get a new abacus, Mate! It was twelve times, each punctuated by bells, whistle, red flashing lights, and much yelling, no doubt all dictated by safety. We arrived exhausted and swore off such travel.

‘The Piano Cemetery’ (2010) by José Luis Peixoto

The Lázaro men are carpenters and in their workshop there is backroom, usually kept closed, full of broken down pianos – the cemetery of the title. That much I got. It is set in Lisbon.

José Luis Peixoto

José Luis Peixoto

It has been well reviewed in ‘The Times’ (London) and ‘The Financial Times,’ and it has many stars in Good Reads reviews. He has many other titles.

This is homework for our Iberian travels in the future.