The Rabbit Factor (2020) by Antti Tuomainen

Good Reads meta-data is 301 pages, rated 3.78 by 5,053 litizens.

DNA: Finland.

Verdict: A hoot and a holler! (The highest rating.)

Tagline: The Rabbit did it, twice.

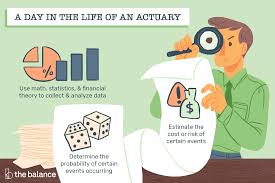

Actuary is McKinsey-managed out of his 15-year position after being tortured by an open plan office with weekly ‘soft flow’ training sessions to release his inner creativity. The open plan office makes it impossible to concentrate on all the possibilities and assign them values, and the soft-flow training induces nausea in his hyper-rational mind. He has no inner creativity, nor does he want any.

At age 39 for the first time in his life, he is unemployed. Well, no problem, as long as people die there will be work for actuaries. He thought. He was half right. People still die, and more to come, well, to go. He was half wrong because the schools are churning out more mathematicians than anyone knows what to do with. Employers don’t want experienced actuaries who are set in his ways, they want young and strong employees desperate for their first job. Having never spent a Euro in vain, Actuary sits tight on his savings and waits, and waits, and waits with Schopenhauer to keep him company. Hmm.

Then things get worse. His seldom-seen brother dies. Oh, well, he will do the duties that need to be done in a cost-efficient way. It is then that he discovers he now owns his brother’s adventure park, and also his debts, both white and black. Then there is the rabbit.

The ride is slow and unsure, and then wild and unpredictable. Despite the odds, which he has carefully calculated, Actuary discovers things about the park, people, himself, and life. His reaction to art and the artist are charming, if life threatening. I will never smell a cinnamon bun again without flinching.

The managementese interspersed throughout alone is worth the cover price. A close second are the musings of Schopenhauer — in both incarnations — that are interspersed in the text. But then there are Actuary’s efforts to reduce his decisions to Gaussian equations!

Loose ends remain. Johanna runs the kitchen with an iron hand in an iron glove and never wastes anything. That combination made me wonder what she did with freezer man.

This is the third title I have read from this author, and I am very glad I did. The first was so-so, but I liked the north woods setting and finished it. Another was more diverting and I finished that, too, but this is the cake-taker. No, not the cinnamon bun-taker. No way! I have my eye on its two mammalian sequels. Stay tuned for further updates.