Olivier Zunz, The Man Who Understood Democracy: The Life of Alexis de Tocqueville (2022).

GoodReads meta-data is 472 pages, rated 4.08 by 37 litizens.

Count Tocqueville’s life’s work was the reconciliation of liberty with equality. It began when he was twenty-five and went on to the end. Liberty can only exist if it is self-limiting. Democracy with its countervailing institutions might offer a means to that end. This is a counter-intuitive conclusion because for most people liberty means license, that is, no limits, meaning anything goes. Of course, if anything goes, liberty will soon destroy itself, e.g., shouting fire in a darkened theatre.

This self-destructive tension pervades and explains everything he did and wrote.

John Stuart Mill put it this way: the maximum liberty consistent with a like liberty for all. We can only be as free as everyone else, and vice versa. By the way, he and Mill were correspondents, and Karl Marx may well have been in the British Library on the days Tocqueville visited with Mill.

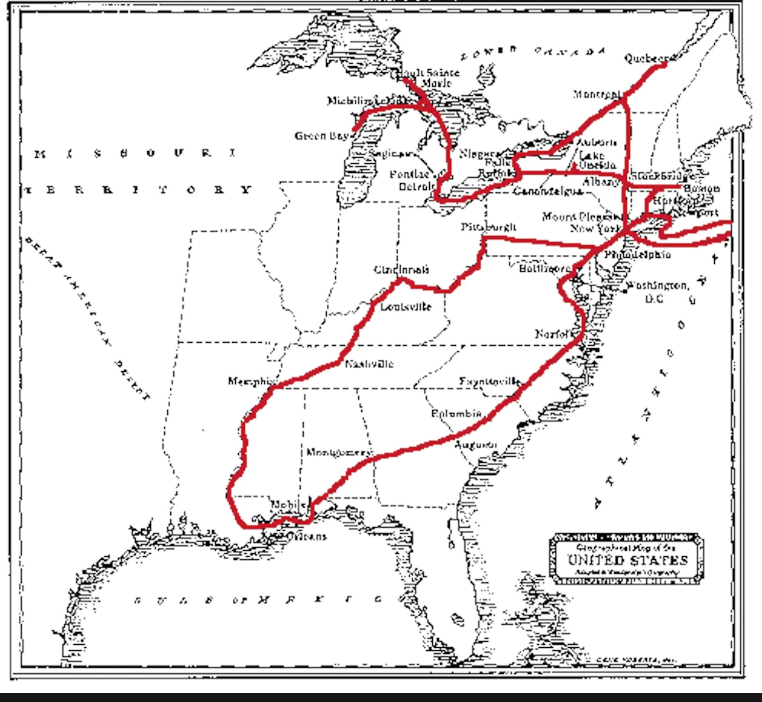

It all began when as a bored lawyer with little to do, Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-1859) and his friend Gustav de Beaumont (1802-1866) went to the New World in 1831 for nine months, which to them was less a geographic than a political expression. The New World they wanted to see (and to report back to France upon) was Democracy which happened to be located in North America. Making use of their aristocratic connections during the reign of King Louis-Philipe, they got themselves commissioned to study prisons. This writ related to a movement to reform French prisons to rehabilitate inmates rather than only to confine or to punish them. The commission gave them letters of introduction and entrées to French counsellors but no financial support. The trip was funded by their families.

They did visit many prisons like Sing-Sing and they did write a report (1833) which few either read or cite. More importantly, Tocqueville wrote the magisterial Democracy in America, and Beaumont wrote novel called Marie (1835) (about the evils of slavery and racism which he had seen).

The trip itself is worth reading about: they went by ship, steam boat, canoe, barge, horseback, foot, raft, dog sled, mule, and stagecoach from New York City, Boston, Montreal, Quebec, Detroit, Sault St Marie, Green Bay, Pittsburg, Cincinnati, Louisville, Nashville, Memphis, New Orleans, Mobile, Columbia (SC), Fayetteville (NC), Norfolk (VA), Baltimore, Washington (DC), Philadelphia, and many points between from May to March of the next year through swarms of mosquitos, boiling heat, enervating humidity, hail, driving rain, sleet, snow, over black ice, and repeat. See Anne Bentzel, Travelling Tocqueville’s America (1998).

They met all manner of people from President Andrew Jackson, former president John Quincy Adams, Davy Crockett, Sam Houston, to rising magnates, and French-speaking native Amerindians around the Great Lakes, German immigrants who spoke no English, and more. This trip and these experiences were the formative years of his life and later as he wrote the two volumes, the experience made him the man he became. The book was his teacher as he ordered, culled, refined, discarded, reinterpreted, digested what he had seen, heard, and learned, and it changed his mind about many things. To be sure, the man certainly made the book, but the book also made the man.

Having seen France go through one cataclysmic disaster after another, each of its own making, Tocqueville hoped to find a new way to live in Democracy and to communicate it to his fellow citizens. This ambition was no abstract exercise for him. His parents, just married, had been arrested and sentenced for the crime of birth to the guillotine during Robespierre’s Terror. They endured 10-months or so on death-row waiting for their turn at the blade, such was volume of prisoners, as all of his wife’s family from her aged great grandfather to her teenage nieces, nephews, and cousins were beheaded one after another to the audible cheers of the crowd. They were spared, and later Tocqueville was born, only when Robespierre was ousted and there followed a brief respite in the blood-letting.

The author avoids the pious homilies that others shower on Tocqueville when he points out more than once the obvious that he missed, like the suppression of his Catholic brethren in New York City and Boston, like the emerging political machines in those cities, like the continued theft from Amerindians, like the oppression of French in Canada and the Irish in the States, the early gestation of the abolitionist movement in Boston, and so on. Nor did he have much of an eye for the wonders of nature. There was so much to take in and almost all of it was new to this ingenue, so that he did not perceive it all.

What he did have was a thirst for knowledge, and he filled one notebook after another with observations of towns, crossroads, inns, street scenes, hotels, and endless interviews with all and anyone would talk to him. He spoke a fractured English swotted up during the sea voyage to New York. In addition to the high and mighty he met, he also talked to wagoneers, hunters, inn keepers, travelling salesmen, farm wives where they bunked en route, gamblers, deck hands on river boats, a day labourer at a harbour, and a slave or two. When they took ship to return to France he had three large steamer trunks filled with the notes and artefacts he had collected from government reports to a bow and arrow and a buffalo rug.

As he travelled through North America he hatched the idea of a book on democracy, but upon return he and Beaumont decided they had to write the prison report immediately to complete that obligation. They did so post haste: On the Penitentiary System in the United States and Its Application to France, which runs to 300+ pages, nearly half of which being appendices of notes and documents. What they found was no system at all but variations between and within states. A great deal of hindsight has been applied to this report by scholars in search of a topic.

Tocqueville is so judicious, careful, and hesitant in Democracy in America that he gives lengthy accounts of opposing points of view, subsequently providing ammunition for others to quote for and against every proposition he considers. He can be quoted for and against democracy itself, since he recognised and catalogued its flaws and failings. Moreover, he did not suppose the American example could be transplanted to France, so he did not recommend that, but rather sought, and continued to seek, the underlying mechanisms that could be developed in France. Hence, his later research into the origins of the French Revolution, where he elaborated what a hundred and fifty years later would be called the J-curve explanation of revolution. (Look it up, Mortimer.)

Every US President, except for the illiterate one, has had occasion to quote, cite, or refer to Tocqueville, yet one suspects that they have seldom turned a page of Democracy in America (1835 and 1840), making it a classic that fits Mark Twain’s definition perfectly. It is widely cited and equally unread. I have to plead guilty to that charge. I bought the abridged student edition of the two voluminous volumes when I was an undergraduate and read whatever was assigned at the time and no more. Since then I have picked over other sections when investigating this topic or that. I tried and failed to read the long chapter ‘The Three Races.’ It is a safe bet that few, very few, of those who quote from Democracy in America have read even as much as that, and sure thing to bet that they have not read more.

By the way, while topics like the tyranny of the majority command many citations, one of the best parts of the book concerns the development of public opinion in the spiral of silence.

See also, as reviewed elsewhere on this blog, Leopold Damrosch, Tocqueville’s Discovery of America (2010).

By the there is a phd to be had in a comparative study of theorists in parliament, Tocqueville, Mill, and Max Weber had a term in office. Who else?