Those good old days! Before Dawkins. (Don’t know what a Dawkins is? Hit google for “John Dawkins.”)

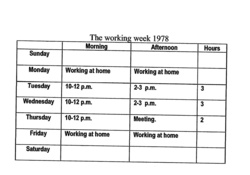

A second obvious change over my years of service at the University of Sydney is the use made of the campus. In the 1970s and later it was a Human Right for lecturers to do all the teaching and office work they did between 10 a.m. and 3 p.m. Tuesday and Wednesday. The justification for this compressed work week was that students would not come to classes scheduled at any other time. This point was explained to me in pitiless detail by several colleagues whose names I well remember.

It was a message that I did not receive. By my second year, I scheduled classes at 8 a.m. and on Friday afternoons. Those colleagues who said to me “They won’t come” were wrong about that, as about so much else, I discovered. Students came and were glad to do so, since their choices were electives, to get some classes done so they could go on to other activities. Even then there were part-time students who had other commitments of work or family. Yes, even in those Golden Days of Yore so beloved by those with faulty memories, there were students who had part-time jobs or were part-time students. The real and final justification for scheduling was always the convenience of lecturers. I add that my efforts to extend the working day and working week enjoyed very little support. At least one Head of Department tried to talk me out of it.  Nor did colleagues respond well. It was just further proof, quite unnecessary, that I was a jerk. So I heard from a student, reporting to me on a remark made about me by a learned colleague. I might add by way of qualification that students had free choice of electives, nothing I scheduled was compulsory for any individual. Of course, once they chose to do a unit I taught, then students had to comply with the schedule. Yes, Virginia, but the schedules were known to students before they chose, and they could change for a while (too long) after the classes began.

Nor did colleagues respond well. It was just further proof, quite unnecessary, that I was a jerk. So I heard from a student, reporting to me on a remark made about me by a learned colleague. I might add by way of qualification that students had free choice of electives, nothing I scheduled was compulsory for any individual. Of course, once they chose to do a unit I taught, then students had to comply with the schedule. Yes, Virginia, but the schedules were known to students before they chose, and they could change for a while (too long) after the classes began.

Those 10 a.m. – 3 p.m. lecturers were busy, while at the office, for the two or – if they were applying for promotion — perhaps three days a week they visited.  The noteworthy exception was Pay Day. In those days before internet banking, pay day stimulated apparently superhuman efforts by some lecturers to get to the office, and once that effort was made … recuperation took time. In the tea room (on that institution there will be more later) I once had the benefit of sermon from a colleague who was explaining to me that I would only understand some particular aspect of the place once I had been there as long as he had been. Hmm, I thought I had already spent more time there, on campus, than he had, since I was there every day, unlike him. I said that. Hmm, no wonder many colleagues found – find – me a jerk. Calling pompous bluffs like that.

The noteworthy exception was Pay Day. In those days before internet banking, pay day stimulated apparently superhuman efforts by some lecturers to get to the office, and once that effort was made … recuperation took time. In the tea room (on that institution there will be more later) I once had the benefit of sermon from a colleague who was explaining to me that I would only understand some particular aspect of the place once I had been there as long as he had been. Hmm, I thought I had already spent more time there, on campus, than he had, since I was there every day, unlike him. I said that. Hmm, no wonder many colleagues found – find – me a jerk. Calling pompous bluffs like that.

The members of the general staff in the Department office were trained to say of the absent lecturers that they were working at home. I always admired the straight-faces with which general staff said this. Little sign of this prodigy of homework, if based on the hours not at the office, was ever seen. Those who worked at home the most, published the least, returned assignments to students the slowest, and came unprepared to meetings. (Relations between academic staff and general staff are another subject for comment later.)

In short, in those hazy days before John Dawkins became Minister with responsibility for Higher Education, the working week was abridged to two, or at most, three days. It was further reduced by declaring 1-2 p.m. to be the sacred lunch hour when nothing could be scheduled. I was lectured on the inviolability of this hour, too. Then there were the Department and Faculty meetings. Because the early and mid-1970s had a storm in every tea cup, there were constant meetings. Department meetings were scheduled every Thursday 12-2 p.m. and we met at least twice sometimes four times a month. (On those Department meetings, more later.) Faculty meetings were monthly on Fridays, and there were often two of those a month. There were ever fewer hours left. Accordingly, classes, committees, meetings, supervisions, and the like had to be accommodated in between 10 a.m. – 1 p.m. and 2-3 p.m on, at most, three days a week. For many it added up to two four-hour days in an eight hour week. No wonder members of the academic class were so quick to the barricades (on Tuesdays and Wednesdays) when conditions of employment were examined by the Canberra paymaster.

Though I admit we never reached the standard John Stuart Mill set.  He noted somewhere that his duties at the India Office never took more than one hour a week. Bleaders are invited to provide the source for this claim by Mill.

He noted somewhere that his duties at the India Office never took more than one hour a week. Bleaders are invited to provide the source for this claim by Mill.

Needless to say, but say it I will, there were honourable exceptions to these generalizations about time spent on campus, but understand that is just what they were, exceptions. The scheduling of classes was the property of lecturers. If a lecturer wished to take into account in scheduling the interests of students, say those with part-time jobs, that was optional. If a lecturer thought a work ethic dictated a five-day week, well that is one lecturer’s opinion.  Thus was everything reduced to the quirks of personal preference.

Thus was everything reduced to the quirks of personal preference.

Since those days we have hesitantly extended the teaching (and by implication, if not fact, the office week) from Monday to Thursday. There is little or no teaching on Fridays in the part of the jungle I walk. And we have extended the hours. In particular we teach in the evening, though some think the evening starts at 4 p.m. (see next paragraph), so that classrooms may in use from 8 a.m. to 9 p.m. In addition, we teach on weekends with some regularity. Bad enough? Yet there is more. We also teach in summer school in January and February thanks to air conditioning, and in July between semesters. It is a four semester year. If the reforms John Dawkins set loose those years ago were partly inspired, as he said at the time, to get more use from the assets of universities, it has certainly worked.

Another of the wars of words has been over what the meaning of the word ‘evening’ in the phrase ‘evening teaching.’ Here is how Wikipedia defines ‘evening:’ Evening is the period between the late afternoon and night when daylight is decreasing, around dinner time. Though the term is subjective, evening is typically understood to begin before sunset, during the close of the standard business day (about 6 pm) – and extend until dusk, the beginning of night. Evening thus spans the period of twilight, but begins before it and depending on definition may extend past its end. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evening But I am sure a self-regarding seeker can find somewhere another source that defines “evening” as 4 p.m.

Many loose ends surround the extension of the working day and the working week. Information and administrative offices are seldom open after 5 p.m. and never on weekends. Getting food on campus just before a 6 p.m. class in Summer School is a very long shot. There is no point in even trying for food on weekends. For the information after hours, students are referred to web sites. For food after hours, there are a few vending machines, when they can be found. But I fear a critic would observe that offices closed at 5 p.m. and food was not available for some long time before internet and vending machines came along. Teaching on Friday remains rare. It has been said recently to me in 2010 that students simply will not enrol in or come to Friday classes. An echo from the 1970s in 2010. Hmm, I taught on Friday many a time with a full house.

The transition to longer hours of use has been slow, a kindly observer would say.