I spend my life in academic circles. Round and round I go. While circling I sometimes notice what other people are saying. Can’t be helped.

One of the things I notice them saying is a general contempt for, derogation of, and enthusiastic debunking of great men and women. Here as in so much else the academy mirrors the wider world among those journalists, bloggers, Facebookies, and writers who think of themselves as intellectuals with self-appointed role is to be critical of our culture, well, really of everything.

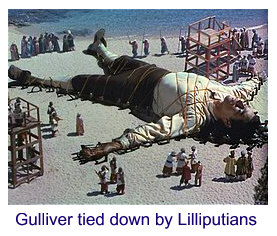

Bringing down the great is a blood spot. Here these Lilliputians are hard at work:

The biographers spare us no detail about hair dye, punctuality, reading habits, pain-killers, alcohol, the shenanigans of offspring or siblings, and – and in the great tradition of the mess media (that is not a typo I mean “mess media”) saving the best for last: sex. There is no matter too small, too private, too irrelevant that it is not touted, shouted, and blogged to diminish and to demean the great.

“Quiet up there in the back, I will say what I mean by the ‘great’ in a moment. Right now I am setting the scene. Take a deep breath and count to ten, while I go on.”

I have seen every one of the items listed above trotted out as if it were the news of the moment. Did the premier dye his hair? If so, will he admit it? If he does not admit it, is it a deceit that goes to the heart of his character? One imagines the empanelled Sanctimonious Ones on ABC1 wisely nodding heads. On SBS the journalists interviewing each other would furrow their brows. One reaches for the remoter! “On his deathbed a former US president was reading a Western novel!” Shock! Horror! That one was presented to despoil the legacy of a two-term U.S. president. Punctuality? Well a British prime minister was always late, so the foreign policy of that government was suspect. All of this is noxious enough but more genteel and abstruse versions of the same approach exist in the academy. There they pass for more than entertainment.

In classrooms bespectacled, bearded, uncombed, bejeaned lecturers, for whom finding a parking place is THE major challenge of the day, sarcastically belittle the likes of Winston Churchill for the titillation of undergraduates. Much of social science is always the assault of pygmies on giants.

In another context Churchill once said, now that the war of the giants is over, the wars of the pygmies will begin. He meant that now that World War II was over, there will be fights over the remains. See The Irrepressible Churchill, ed. by Kay Halle (1966), p. 249. Exactly so.

That assault goes on with renewed vigour these days. That which is so far from our own experience we scholars ridicule. Thus does Homo Academicus rule. Of course, armed with PhDs, we are clever enough to conceal our jealous ridicule in polysyllabic terminology borrowed from the French or the German to make it sound important.

The ‘great,’ by the way (I said I would get to this term), are those that have to face those terrible challenges that life deals out to but a very few and who have prevailed: War and peace, life and death, now or never, and the like on a national or international scale. Presidents, prime ministers, generals, citizens in the firing line, these people have to do something that affects a great many others. Action not discourse analysis!

Among those that do have to face these matters, some enter the pantheon of greatness, as Winston Churchill, who was voted the Greatest Briton in a BBC exercise a few years ago. No sooner was the last video broadcast confirming that Churchill was the Greatest Briton to the British people, than the scholarly detractors searched the mental soft disk for the old notes setting to rights Churchill’s claims to fame. Though long dead, he is still a good career-making target for the pygmies. (Yes, I know about evil and incompetence on a grand scale, but that is not the focus here. Do pay attention.)

Churchill, they said, was not great because … he did not rescue enough Jews, he invaded Norway, he did not invade Sweden, he either did not help Greece enough or helped Greece too much, he was wrong about India (was he ever!), he was but a nationalist just like Hitler, he drank too much, he took too many risks, he did not take enough risks, he did not hold war time elections, and the list still goes on. The list is so long that it becomes difficult to see why we once, evidently mistakenly, thought so highly of him. Abraham Lincoln has been periodically accorded the same debunking. As has just about everyone else from Jean d’Arc to Sister Teresa. Only the mediocrities escape the opprobrium. Chester A. Arthur’s good name is safe from the attention-seeking scholar or journalist.

In a televised panel discussion on the ABC a noted journalist, well he said he was noted but I had never heard of him before or since, said in passing of John F. Kennedy “now we wonder what we ever saw in him.” This from a scribe who never went near a nuclear button over Berlin, never contemplated the missiles of October, and still less was never responsible for the lives of the crew of a PT boat rammed by a Japanese destroyer in the darkness of night in a black sea. My goodness how smug and superior we can be, we who have faced the parking lot crisis.

Having come this far Reader, and I know some slackers have not stayed this long, there is a larger point here about how social scientists, and the replicators in the mess media, see the world. To keep it simple, there is structure and there is agency. To a social scientist, just about everything that happens is due to structure. Agency, taken to mean the unique, sui generis contribution of individuals, one at a time, explains virtually nothing, and so is not taken seriously. Social forces are massive but invisible and impersonal, and they explain everything. Emile Durkheim laid the foundation for the concentration on structure with his remarkable study of what seemed to be that most private and idiosyncratic of all acts, suicide, and showed the social causation that explained variations in its occurrence.

Social forces may be economic, religious, ideological, or political, or social and they flow through the world, rather as the atmospheric highs and lows that we never see, determining the social weather. Exemplary individuals are created by the patterns of these social forces, as are thunderstorms. It is this context that an analyst can say that as colourful and extra-ordinary as Churchill was with all his habits, tics, and contradictions, none of it was unique to him but rather created by the English class system, its political expression, and the like. Had the individual we know of as Winston Churchill been killed crossing the street in Manhattan while on a speaking tour in 1929, as he very nearly was, then somehow or other Britain would still have held out until the United States and the Soviet Union tipped the balance in World War II. It is not quite determinism but it almost sounds like it. But leaving that aside, the point is that the dominance of structure leaves no room for the expression of agency, when all of the fine points have been pointed, the qualifications qualified, and the quibbles quibbled, if ever that end is reached.

Indeed in some sense, social science grew into a profession in reaction to the explanation of events as the actions of great men in history by Thomas Carlyle. The social sciences arose to study society as itself causative, leaving aside the greats, as well as the smalls (we mere mortals).

Every social scientist knows that structure prevails in every important way and they say this in the research they do and in the classes they teach (yet, I suspect, they harbor the belief that they are creative individuals – agents, themselves an exception to the rule they preach). Accordingly social scientists routinely decry the great man in history focus on extra-ordinary individuals like Winston Churchill.

Social science took individuals out of social explanation. It was in reaction to this dehumanizing of social life that leadership studies emerged. Sometimes leadership studies descend to a set of steps to follow to be a leader, a sort of Churchill’s Handbook approach, which by implication denies uniqueness to Churchill while attributing agency to him. “We can all be little Churchills, if we try” is the message. That message is ludicrous but it does answer to some need because those books about leadership are legion. The covers change and the titles come and go, today’s talk-show sage is forgotten tomorrow, but the books on leadership spill off the shelf. The fact that there are so many of them itself suggests that readers believe there are leaders. Something social scientists know is just silly.

Well, many social scientist act as if they know that when they denigrate Churchill, though as noted above, they may also think of themselves as exceptions to the rules they apply to him. The academic custom of making oneself an exception was codified by Karl Mannheim when he wrote of ‘free-floating intellectuals’ who are in but not of the society, and so able to perceive its structure. Try his Ideology and Utopia (1929).

The representatives of the mess media do not have deadline-time to go into any of these doubts and qualifications, so they say. They do have time to smirk, sneer, and opine – they call it subjective journalism, I am told – sure in the faith that any claims to leadership are dishonest, false, and dangerous. (It seems sometimes to be a collective and endlessly rerun Watergate investigation: one leader became a crook, therefore all leaders are always crooks.)

A journalist was once waxing on about the void of leadership everywhere (except, by the implication of silence, in the mess media) when one interlocutor demurred and said ‘no man is a hero to his valet.’ It was a show stopper.

Since the interlocutor was not a native speaker of English the words came out with the emphasis on the wrong syllables, and true to form, this journalist could not seem to understand English spoken by someone who does not speak Leagues-club English. So the remark had to be repeated a few times for the compère to get it. Then it had to be explained.

Here is the explanation: The valet does the laundry, makes the bed, tidies the closet – this is the world of the valet, that is all the valet sees of what the employer does. Napoleon’s valet saw only dirty socks, ripped jackets, and other detritus. One person’s dirty socks are much like anyone’s dirty socks, so there is nothing in the valet’s world distinctive about Napoleon. And that is the point, no man is a hero to his valet (it was said by Georg Hegel) not because no man is a hero, for some clearly are, like Napoleon (in this case ‘hero’ can be taken to mean larger than life), but because the valet is only a valet, i.e., lives in the valet’s world where dirty socks are the reality. Hmm. Most journalists these days are content with dirty socks because they seem only to see the valet’s world.

By the way the compère’s confused and condescending response to this aphorism from someone whose English was not League’s-club standard was a clear example of a more general phenomenon. Members of the Australian mess media sometimes seem unable to understand English from non-native speakers in a way I am told Japanese just cannot fathom Japanese, even letter and tone perfect, spoken by a European. Hence those ABC television news items with subtitles for a speaker who is perfectly clear, if labored, in English. Remember those Dutch bankers in the 1980s who went to Perth to question Alan Bond’s many instances of creative accounting, long before it unravelled, in heavily accented English only to excoriated by the mess media for challenging our great man (see, yes, I know claims to greatness can be dangerous, salt can be dangerous, too, but it is part of life). For a time the pygmies preferred nationalism. But that changed.

No, most people probably do not remember these Dutch bankers because when that great man’s fall came this part of the story was sent down the memory hole by those in the mess media who latter wanted to take credit for his downfall. Only those with clipping files retained it.

2 thoughts on “Pygmies and giants”

Comments are closed.

Nice job. The term “mess media” which describes it well 🙂 As a budding journalist, or at least studying for such, I admire the arugments and reasoning! The idea for comparison between the valets and the journalists, judging without any perspective, is just brilliant! Really,there are so many things for me to be learnt from your post!

No matter if we are faced against a giant or pygmies, we have to select the battles we participate in- this is one of the most complicated philosophies in life- to judge which battle is worth it and which not.