The genre is the academic novel. That category might make one think of Tom Sharpe, David Lodge, Malcom Bradbury, Mary McCarthy, Kingsley Amis, C. P. Snow, or the ineffable Willa Cather. But John Williams is in a class nearly by himself in Stoner (1965).

Williams’s prose is windowpane clear. The emotions of his principle character Stoner are deep but nearly silent and all the more elemental. Stoner is surrounded by people who do not understand him, and lives his life entirely in their company.

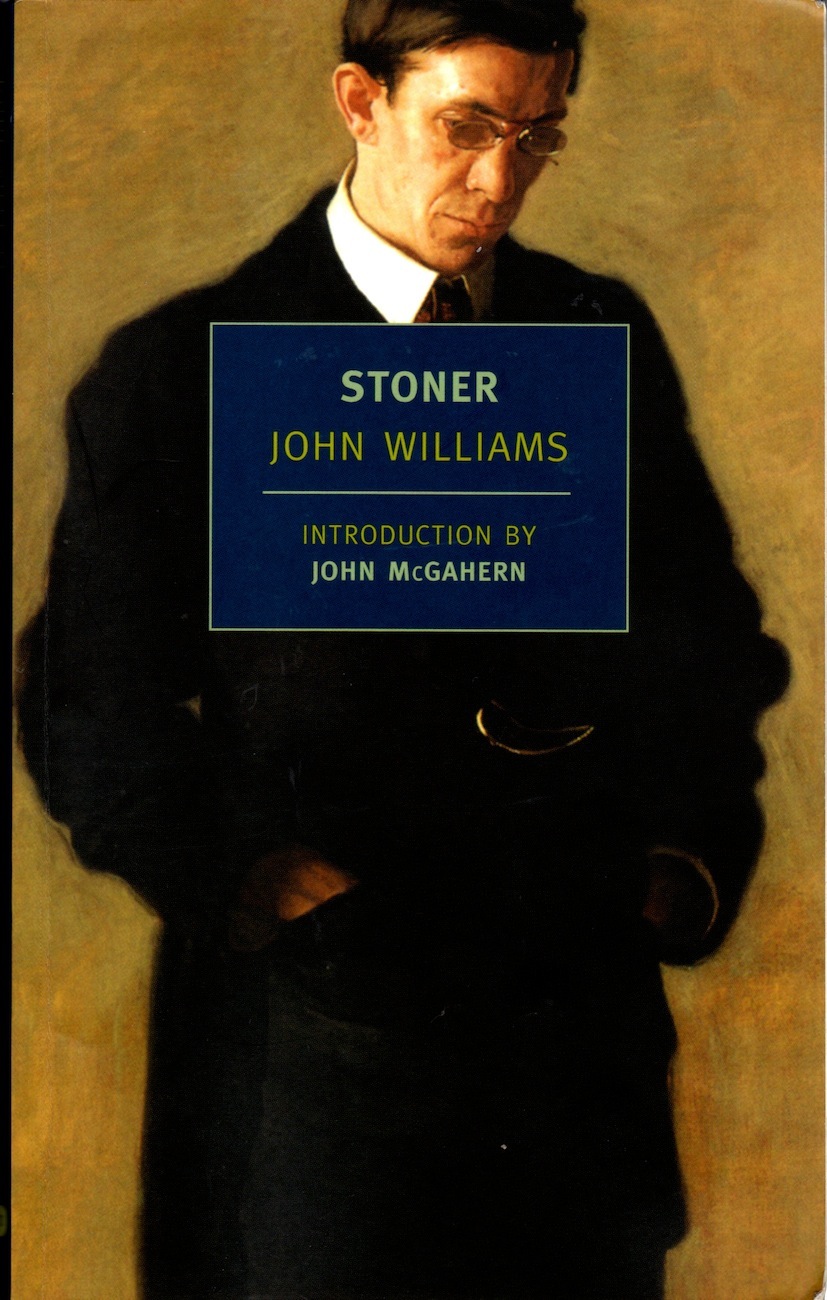

http://www.amazon.com/Stoner-York-Review-Books-Classics/dp/1590171993/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1339811528&sr=8-1&keywords=stoner

What is incomprehensible and mysterious about Stoner is that he loves the worlds that words make in books. In the English Department at the University of Missouri between 1920 and 1960, where he passes his days, this love is neither well-known nor highly regarded. That he lives only to read, to write, and to talk about literature makes him an academic failure in the company of career-makers who care nothing for words and ideas.

The accounts of Stoner’s several transformations from boy to student to scholar are marvellous. The best of these transformations is perhaps the last when his hand brushes a book and its pages quiver with life. That is the moment he dies forgotten, unlamented, and unmissed.

I did find the plot mechanical. Edith, the wife, and Lomax, the Head of Department, were ciphers there to bedevil Stoner, but who were otherwise empty of meaning. Nor did I find it creditable that the dean, Finch, would be so staunch. But each of these three characters provides a mirror for Stoner’s reaction and that is enough.

I said that Williams is in a class nearly by himself. Together with him I would assign Willa Cather, The Professor’s House (1925), a seat. She, too, captures something of the wonder and awe of learning that the other scribes listed at the outset are too jaded to realize and probably incapable of portraying.

My thanks to Trevor Cook for mentioning this book.

Skip to content