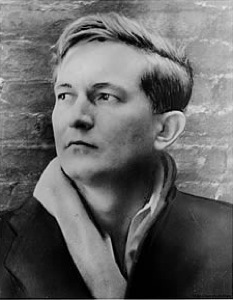

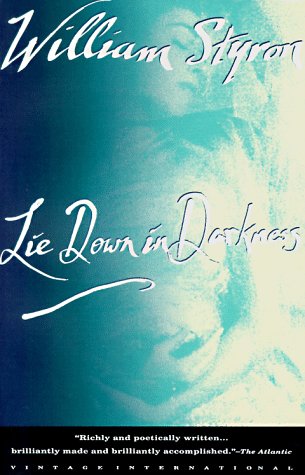

William Styron (1925-2006) published the novel Lie Down in Darkness (1951) when he was twenty-six, a boy. Recommended for adults.

How could a boy have had all those voices in his mind: Milton, the alcoholic lawyer; Helen, the angry, self-martyred wife; the Elektra-like daughter, Peyton; Carey, the childish churchman; and all the others. It was hailed as a masterpiece when it appeared but it has not weathered so well in the eyes of some reviewers. On that more later.

First for the uninitiated it is a southern novel, what has been called, Southern Gothic (for a definition see:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Southern_Gothic).

Styron did not write another novel of this ilk, though he wrote others that are better known: The Confessions of Nat Turner (1967) and Sophie’s Choice (1979). I have already commented on his The Long March (1952). By the way, a reader would never connect the spare prose of that book with the languid and at times moving descriptions of people, places, and gestures in Lie Down in Darkness. The two books seem to come from two different hands.

Recent retrospective reviews that I have read seem to be driven by the need of the reviewer to demonstrate superiority, moral, technical, literary, to Styron and his novel. Thus they comment on the condescending references to blacks, the drumbeat of negation that runs through the story, the unbelievable medical interludes, the inconsistent references to psychoanalysis, the stream of consciousness chapter is labeled imitative of William Faulkner (who thought highly of this book), the Sunday school theology, and even the geography of the story. To read such reviews one might wonder why bother.

Here’s why.

When the needs of the reviewer takes priority over the book reviewed much is taken out of context and rendered disproportionate. The book is no dirge. There are arresting passages of great beauty, as when Helen describes her love of Maudie, the oldest daughter with brain damage and polio; as when the juggler appears in the rain; as when the train rocks through the woodlands of northern Virginia; as when Milton swears off drink (again, and again, and again); and most of all in that stream of consciousness chapter inside Peyton’s broken soul. It is certainly not imitative, transcendent rather.

There are novels of that time and place that do more justice to blacks, agreed, here I think of many examples in Faulkner, but they are few, too few and too singular to be a standard against which to judge this book. Nor does one read a novel to learn of medicine, psychoanalysis, theology, or geography. Let the poet have license.

Of course, there is no explanation of why Peyton was so fated. She just was. That is the premise of the story. The parents, Milton and Helen, blame each other, as mature adults do. But given that she is what she is, then the rest unfolds.

I first read this novel when I was about twenty, not much younger than Styron was when he started writing it, nd that makes it all the more remarkable that he had all those voices in his mind, though he could not always control them each, nor orchestrate them just so. For all of that, it remains a masterpiece.

Tools for underlining, hyperlinking, and other formatting remain unavailable.