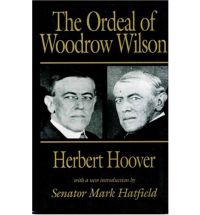

This is a book about a president by a former president. It is unique and must reading for presidentialistas. It is all the more distinctive since Wilson was a Democrat and Hoover a Republican.

Could it happen again? Would a Republican Bush write a tribute to a Democrat Kennedy? Or a Democrat Clinton to a Republican Reagan?

The ordeal is the war and the peace of the Great War 1914-1917, though it only concerns the American participation in the War 1917-1918. Hoover was enmeshed in Europe from 1914 on in organizing food aid for first Belgium and then France, and from November 1918 onward for all of Europe as far east as the Volga River in Russia. It was colossal undertaking that just got bigger.

Hoover worked for Wilson in several capacities, directly and indirectly in these years and some of the work was very intense, urgent, and truly life-and-death. I have traced some of Hoover’s astonishing humanitarian efforts in the review of the Hoover presidential library elsewhere on this blog.

The book was written forty years after the events it describes when Hoover was in his twilight years.

There is no indication that Hoover kept a diary at the time but he certainly kept copious files. In addition to the papers he himself had, Hoover also consulted reams of declassified official files to which he had easy access and he was assiduous.

There is no doubt that Hoover had a great admiration and respect for Wilson, as an intellect, as a moral champion, as a tenacious reformer, as a titan for work, as a man of personal rectitude, and more. He writes in glowing terms of Wilson in nearly each chapter.

The book compiles a great deal of detail on the points it touches. We read about the pounds of wheat in a shipment, or the number of delegates seated around the table at a committee meeting. It rehearses the arguments made in dark days when much of Europe was starving to death between 1917-1919. It produces an anatomy of the enduring antagonism between the French and Germans, the racial hatreds among the Balkan peoples, territorial ambitions of every country involved with the Treaty of Versailles. I certainly found some of that eye-opening.

Yet there is no insight whatever into the subject Wilson. In fact, apart from some laudatory paragraphs at the beginning and end of each chapter, Wilson only appears in the book to support Hoover, to agree with Hoover, to praise Hoover, to ask for Hoover’s help, etc. More than anything else it reads like a log of their business dealings from Hoover’s side.

Robert Lansing, Secretary of State for Wilson, appears here to be the absolutely straight arrow he is seen as in others studies of the time. I stress this because he has sometimes been belittled in Wilson’s shadow. Jack Pershing seems to have been the very man for the hour; when he spoke everyone listened. The rank of general ratified what he already was, a leader. In these pages Georges Clemenceau certainly lives up to his reputation as the Tiger, completely unyielding, hoping to destroy in the peace every German who survived the war. Winston Churchill is preoccupied with retaining the British Empire, despite espousing Wilson’s Fourteen Points. Colonel Edward House is constantly moving here and there though he holds no position, except as Wilson’s friend, a very small club that.

There are a few striking anecdotes. During the Armistice and the never-ending peace talks, American army officers, numbering a thousand or more, were sent all over Europe to keep track of the American food aid flooding across Europe. Long after they had been recalled Hoover got a personal letter from a lieutenant at a railway station in East Prussia who was still recording the train cars going past, asking if he could please get a new winter coat, apologizing for contacting Hoover directly but doing so because no one in the chain of command, long since disbanded unbeknownst to him, had replied to his previous requests. Upon checking Hoover found this dutiful lieutenant from that dreary East Prussian train depot had been telegraphing data to an empty office in Paris for eight months. Hoover made sure this forgotten man was recalled immediately and treated him to a luxurious few days in Paris before sending him to his unit to be demobilized.

Of greater moment are Hoover’s descriptions of the negotiations in Paris. More than ninety governments were represented in one way or another, each anxious to retain every foot of territory and every citizen it claimed, each ready to take more territory and citizens with a list of historic grievances to support expansion, each proclaiming Wilson’s Fourteen Points while violating them, none willing to make a single concession, each distrustful of all the others. What an atmosphere! Moreover, many delegations were even more deeply divided internally. The newly created Republic of Banat (look it up) had a fractious delegation of twelve who each insisted on going around en bloc because not one of them trusted another out of sight. To put one of them on a committee meant putting all twelve on. In other cases there were two or three rival delegations each claiming to represent, say, Osteria. Which one speaks for Osteria?

Rufus T. Firefly of ‘Duck Soup’ would be the straight man here. An ordeal indeed for any sane, rational man trying to do the right thing in such a ninety-ring circus.

Hoover defends Wilson from the common charge of being a hopelessly naive idealist with a compelling and convincing list of the material achievements Wilson made in Europe starting with ending the war, saving tens of millions of starving people, undermining the tide of communism, displacing some murderous tyrants who had risen from the ashes in Eastern Europe, establishing the International Court of Justice at the Hague, creating the International Labor Organization in Geneva, and founding the League of Nations which in turn did much forgotten good and paved the way for the United Nations and the international organizations that exist today.

But most of all Hoover credits Wilson with inserting into the vocabulary of international relations the language of rights, conscience, liberation and freedom that did not exist prior to his oratory. One might say that Wilson translated the emancipatory rhetoric of the the King James Bible into statesmanship, supplanting the existing language of gunboats, maps, spheres on influence, mandates, concessions, and survey lines. That Wilsonian rhetoric remains today. spoken by people with no knowledge or interest in the man Woodrow Wilson.

It is not an easy book to read for many chapters consist of quotation after quotation from speeches, committee reports, newspaper articles, diplomatic assessments, letters, and telegrams strung together with a few transitional remarks from Hoover. In hindsight Hoover has no second thoughts and no feel for the human drama all around him in those meeting rooms. But what raw material for novelist! Bring on Frank Moorhouse of ‘Grand Days,’ Georges Simenon of ‘The President,’ or George-Marc Benamou of ‘The Ghost of Munich.’

I hesitated to read this book since I found the Herbert Hoover in retirement portrayed the biography I have already read of him so bitter and unforgiving I supposed this book would be merely a record of that. Only a few asides did I perceive that rancor, primed to see it as I was. It would probably not trouble most readers who were not aware of Hoover’s ripened bile.

The forward by Senator Mark Hatfield adds little to the book.

Skip to content