Hannah Arendt’s essay on space flight and humanity is a meditation on the impact of technē on us. It was written in 1962 long before smartphones, tablet computers, medical wrist bands, iWatchs, slave cameras, iris identification, bio inserts, and the like. Yet with a few changes it anticipates this world now, more than fifty years since she typed it. (Yes, as readers of biographies know, she typed the first several drafts of all her works herself.)

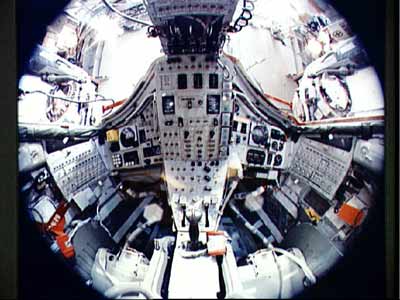

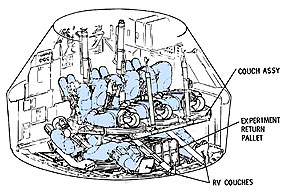

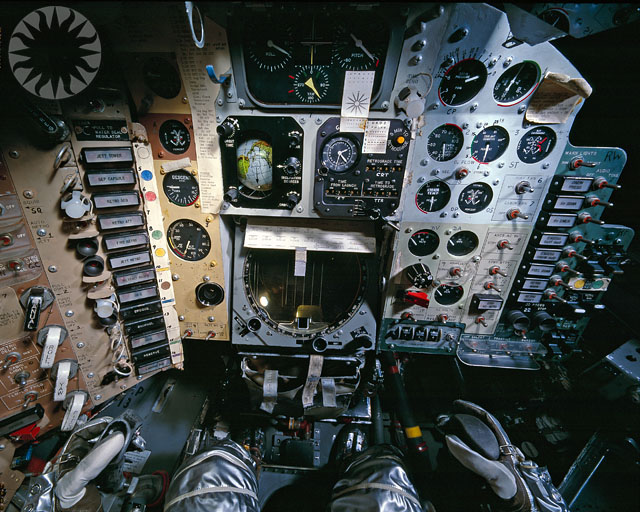

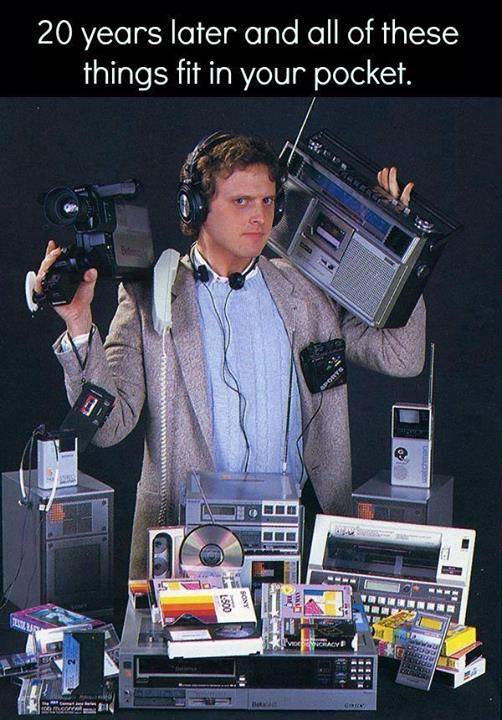

The changes would de-emphasize space flight with all the gadgetry and gizmos that go with it to protect the person and extend the astronaut’s ability inside the machine of a rocket, lander, or gravity suit. Instead of this kind of technology, it would refer to digital layers that now beguile and enfold us.

To make these digital technologies work, we have to cooperate with them, just as astronauts had to do with their equipment. We have to care for them. We patiently wait for them to boot-up. We keep them in cool environments so that they do not overheat. We feed them electricity, sometimes in carefully regulated doses to keep the batteries charged. We present ourselves to them in ways they can recognize, accept, and respond to whether that it through a keyboard or stylized gestures. We keep them charged up. We keep updating the app software. We discipline ourselves to work with the devices. (No one calls them machines, though that is what they are.)

The more the technology does for us individually, the more willing we are, one-by-one, to meet it halfway, or more.

It all fits into the smartphone which fits into a pocket. Smaller and smaller gets the smartphone, so small soon that…. Use the imagination.

In some places now a person has a single telephone number that incorporates both a fixed landline at home and a mobile number. Once that number is mine, it remains mine even if I move to another home. That number is me … and I am that number. Like it or not, I am my telephone number even if I don’t resemble it.

Imagine the day when that telephone number merges with my Social Security Number, with my tax file number, with my Medicare number, with my VISA card number … That day will come. (Pause to think of all those totalitarian nightmares of dystopian and science fiction writers.) In fact, in this scenario the metadata is me in all important aspects. Publicly no one needs to know my idiosyncrasies, opinions, or needs, all that counts is the relevant bar coded number to scan.

In the face of these temptations, Arendt urges readers to reverse Descartes, to ‘I doubt, therefore, I am.’ How that translates to digital technology, that is the question for today. She did not have to face that question directly since the space technologies that fascinated her, were not consumer goods. There was no iGravity Suit. But as always what she meant was to think, not to react, but to think. Reacting is easy, thinking is hard, slow, and sometimes wrong.

The full integration of these digital technologies will erode, compromise, limit, and, perhaps, destroy our humanity. We will slowly and voluntarily become Borg. I may never resemble my phone number but I am nothing but that number, despite my vanities. I published an earlier piece along these line as ‘The beast that blushed: on modern manners,’ ‘Spectrum, Sydney Morning Herald,’ 30 September 2000, pp. 6-7. (Speaking of vanities.)

No, she did not refer to the ‘Borg,’ bio-mechanical creatures who inhabit the fictional world of ‘Star Trek.’ But they may exemplify her conclusion in some way. Her fascination with technology traces to homo faber in her book ‘The Human Condition’ (1958).

Arthur Eddington once said it was foolish to suppose that he resembled his telephone number, it is said, but I found no text to support it.

Skip to content