A wide ranging study of Richard Nixon — the man, the career, and the times that shaped both the man and the career. It is uncanny in the way it a foreshadows Nixon’s self-destructive impulses: his paranoia, his introversion, his secrecy, his distrust, his self-doubts, his insecurities which combined to lead him to Watergate’s half-truths, deceits, prevarications, denials, lies, enemies list, and so on.

The Nixon that emerges from these pages is hardworking, and always over-prepared for everything, a man who scripted and edited his every word and gesture. If he seemed wooden and without spontaneity it is because he was his own puppet master, jerking the wires to jaw and arm. Supposing himself to lack the assets of others (the personal charm of Charles Percy, the grace of William Scranton, the wit of Adlai Stevenson, the courage of John Lindsay, the gravitas of Robert Taft, the respect accorded Dwight Eisenhower, the dignity of George Romney, the mental agility of Harold Stassen, the experience of Henry Cabot Lodge, the wealth of Nelson Rockefeller, the good looks of John Kennedy) Nixon compensated for all these these gifts bestowed on others by working longer and harder than anyone else with that famous “iron butt.” Everything he ever did in public was practiced, rehearsed, revised, practiced, rejected, redone, and so on until he reached the robotic result we all saw.

He would never give in to the human impulse to look at his watch while listening to a voter rant as George Bush (once did and was excoriated for so doing).

If Nixon throughout his career looked tired it was because he was, not having slept but instead planned, edited, and revised the next day’s every word and gesture. Nixon never trusted himself still less anyone else. This deep-rooted sense of inferiority seems to have come from nowhere; his childhood and family life before politics are numbingly ordinary.

As early as 1952 Nixon supposed that even members of his own party despised him (for his lack for such gifts as mentioned above) and this conclusion made him all the more determined never to put a foot wrong. One result of this determination was his distinctive reluctance ever to say anything in his own voice; instead he would say: “as a voter I met in Arizona said…,” or ‘as President Eisenhower said…,’ or ‘sources close to the Prime Minister said,’ and so on. It is likely that the first few times these attributions were true but in time it became a habit to distance himself from himself. Wills describes how Nixon reacted to his own successful nomination in 1968 as an example. Convincing.

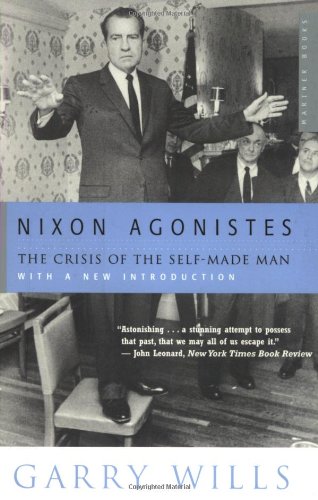

Nixon leaving the White House after resigning, giving his victory gesture. ‘Victory?’ Nixon-logic.

Then there is his first inaugural, an embarrassing parroting of Kennedy’s, as if somehow to capture that magic. This Nixon reminds me of Kenneth Widmerpool when Barbara Goring poured the sugar bowl on his head (or the earlier banana incident); he was grateful to be noticed: even if as a fool. (Widmerpool is the central character in Antony Powell’s magnificient twelve volume novel, Dance to the Music of Time.)

The chapters were magazine articles on the 1968 US presidential election, and so range far and wide. Only three focus on Nixon, but that is plenty. There are also delicious accounts of Barry Goldwater, a man who loved his country so much he refused to saddle it with a lightweight president and campaigned to lose, and lose he did, and Nelson Rockefeller, a Hamlet of presidential politics whose fortune blunted his competitive ambitions and yet who later sacrificed himself rather than jeopardize President Gerald Ford’s nomination. The abiding hatred of Goldwater (acolytes) for Rockefeller is visceral. Apart from that noble sacrifice, Rocky’s finest hour was facing down the Goldwater mob in 1964. It can found on You_Tube as ‘Nelson Rockefeller denounces Republican “extremists” at the 1964 Republican National Convention.’ Those whom he denounced now run the joint.

Though it has nothing to do with Nixon, I particularly enjoyed Wills’s deflation of some of Arthur Schlesinger Jr’s many pretensions. That made me wonder how they cooperated when Schlesinger commissioned him to write the brief biography of James Madison (2002) in a series. Time may have healed that wound.

Wills, for those who do not know of him, is a master stylist, a seeker of facts, an insightful observer, a staunch Catholic, a self-described conservative, a ruthless diagnostician, an astute evaluator, an honest broker among competing ideas, a measured concluder…. He also has tangentites, a condition the spell-checker does not recognise but readers do. Sometime he can neither stop nor get to the point. That combines with some very Jesuitical logic-chopping that seems pointless, albeit spirited. At times he seems determined to find fault in anyone who takes a position, this the luxury of the journalist who never has to do anything as vulgar as come to earth.

Garry Wills

‘Agonistes’ is Greek for contestant.

In 1969 Wills refers to ‘men’ when he means ‘people.’ This will outrage anachronistic style police. I found it distracting and annoying,

Skip to content