A fabulous book about a titan. It will take two entries to review the basics. This is part 1.

It is all there in the title, and I do not mean that word ‘Caesar.’ What I do mean is that it includes neither the definite article ‘the,’ nor the indefinite ‘an.’ MacArthur is beyond those mundane grammatical considerations: one of kind, sui generis. A giant and a midget in one. Astounding achievements combined with a pettiness that seems out of character but was not. He was all one package.

He was widely maligned after the Korean War, and had a lot of buckets dumped on him earlier in World War II. He brought much of this criticism on himself by his unending paranoia that everyone in Washington was out to get him, by his colossal ego in which he was always trying to live up to his father’s mythical reputation, by his absolute determination to see through whatever he put his hand to despite changing circumstances, by his use of moral arguments rather than military one to justify his strategies and tactics though these were genius, by his unsocial nature through which he preserved his mystique but held most people at a distance, by his completely one-eyed devotion to and utter dependence on his wife Jean. He was a hard man to like.

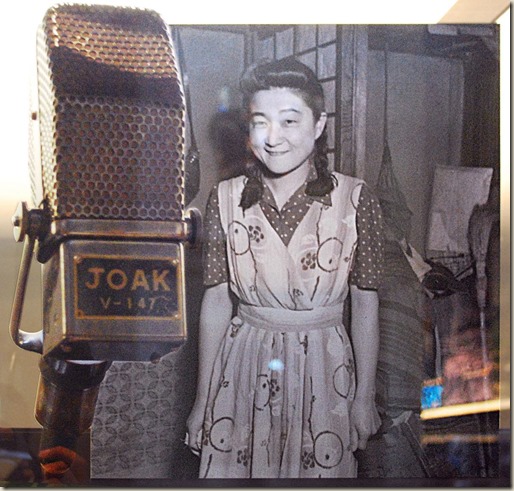

Yet, as William Manchester shows MacArthur was born to the sword though he never carried a weapon yet he was in battle time and after time. He led, he directed, he observed, but he did not pull a trigger. The exception is in Manila when Tokyo Rose

in 1941 broadcasted that Japanese squads were descending on the city to capture him and his family to deliver them to torture, ignominy, and execution. The aim of the broadcast was to frighten MacArthur and thus to show to Filipinos that not even their Field Marshall was safe.

Then he pocketed a revolver with three bullets, giving the rest of the bullets back to the ordinance officer to put to other uses. A typical beau geste from a man who made so many grand gestures that they became irritating. (Reader, tax that brain, figure out why only three bullets were necessary.)

He went over the top in World War I with riding crop in hand wearing the star of a general on his shoulders without either a helmet or a gas mask, he led patrols into No Man’s Land in the night, he stood in trenches attacked by Germans… Those exploits won him five Silver Stars for valor, each well deserved. But his theatrics drove Jack Pershing mad. No division commander should go on a patrol, go over the top, or even be in a front line trench, let alone one under attack.

When carpeted by Pershing and threatened with censure, MacArthur — clearly thinking of Douglas Haig who had never seen a trench, Joseph Joffre who bragged of not have heard a rifle shot, but not mentioning these Allied generals — said he wanted to see what it was like for himself and also it heartened the men to see a general sharing their risks and hardships. Pershing took that as an implicit criticism of himself and ordered him removed from command, Pershing forever joining the mental Enemies List MacArthur carried around for his whole life. As happened repeatedly MacArthur had arranged for his exploits to be publicized to acclaim in France, England, and the United States, and Pershing could not then censor a hero.

It gets worse because Pershing had commanded George Marshall to prepare the order for removal, which he did, and that entered Marshall’s name, too, on MacArthur’s Enemies List. Once on that list, there was no remission.

The occasions in World War II when MacArthur was shot at, bombed, strafed, sniped at, are all too numerous to mention. He exposed himself to enemy fire time after time, in a garrison hat with the stars of command visible. He was on the point with an Australian patrol in Borneo when the two officers with him were killed by enemy fire. An Australian captain pushed him down and screamed at him to leave. Chastened, he did. More Silver Stars came. He had a child-like delight in medals and awards throughout his life. Each one was precious to him. If the Sultan of Obscuria proposed giving him a medal, he wanted to have it. Yet he seldom wore them.

Leaving aside the details, which William Manchester assembles and presents in a compelling prose (without recourse to the adolescent present tense), the best testament to MacArthur’s military genius comes from Japanese war records. They show that they found him unpredictable, deceptive, cautious and bold, and never where they could hit him. In 1942 they thought he would give battle on the plain north of Manila, instead he withdrew into the Bataan peninsula with his forces intact in a move the Japanese described as brilliant. The Japanese had not expected that and were neither supplied nor organized for a siege.

The tunnel was the headquarters on Corrigedor, the island off the Bataan peninsula.

In 1944 he sewed confusion among the Japanese in the Southwest Pacific leap-frogging over their strong points (Rabaul, Wewak) and cutting them off.

Manchester shows that his casualty rate and use of supplies set against destruction of the enemy (Japanese soldiers incapacitated, area taken, time taken) was about ten times, yes 10 times, better than that of Dwight Eisenhower in the European Theatre of Operations, and 20 times better that Admiral Chester Nimitz (he of Saipan, Tarawa) in the North Pacific. The priority of Europe meant supplies were lavished on Eishenhower’s command, while Nimitz hit objectives head-on, signaling long in advance his next target – no subtlety there.

MacArthur would not have attacked a stupendous fortification like Saipan or a deathtrap like Tarawa but would have bombed and shelled each in a demonstration, and then leap-frogged over each to the next weakest island to cut their communication and supply. He would then have left them quarantined and boxed in. He put out of the war a dug-in Japanese army on Rabaul of 120,000 front line troops shipped there especially to give him battle by taking two barely defended islands north of it with the loss of some hundreds of casualties. Nimitz had 27,000 dead marines to take Saipan with its 80,000 defenders. The Japanese on Rabaul stayed there on ever decreasing rations until the Emperor told them to lay down their arms in 1945, so there was never a dramatic American flag raising on it like Iwo Jima, but then there was no comparable butcher’s bill.

On the offensive his many victories were often so quick and, in contrast to the gruesome backdrop of Tarawa or Saipan, so bloodless that they were even not reported back home, and did not enter the annuals as the great strokes they were. In fact, in the Philippines in 1944 he was criticized for moving too slowly by maneuver and not by head-on assault with the overwhelming fire power at his command. His response was public and clear, and as always in the first person: ‘I will take any objective I can by maneuver and feint to preserve every life I can, and I am sure that mothers, wives, sisters, fathers at home want it that way.’ We can be pretty sure the Grunts agreed. But for him to call a press conference and answer criticisms in this way was JUST NOT DONE! But that was the MacArthur way, his way.

Saipan

Like Napoleon at Waterloo, Lee at Gettysburg, or Haig anytime, MacArthur blundered. There are many recorded instances of very successful generals in the midst of a crisis lapsing into nearly a waking coma. Napoleon at Waterloo stood silent for hours, not replying, seeming not to hear the reports and requests of subordinates, which grew more and more urgent. Lee at Gettysburg seems to have entered a trance after he gave the order for Pickett’s Charge early in the morning and stayed that way for the rest of the day, even though it was clear things were going wrong even before Pickett’s men moved into position to carry out the order. Who can wonder at it?

The pressure, the burden these generals had borne for so long, the momentous events before them, the responsibility of the blood, these would crush most of us.

MacArthur had such moments, too. During the New Guinea Campaign, he had tried everything to avoid a direct assault with aerial bombardments, naval attacks, feints around the island, commando raids, and none had sufficed. Time demanded action before the Japanese could be reinforced. The result was the Kokoda Trail. No Australian needs to be told about this battle (though the spellchecker does not know it) in which nature took five (5) soldiers for everyone lost in action. While it raged in conditions straight out of Dante’s Hell, MacArthur had such a comatose period when he seems to have tuned out, sitting at his desk at times like an effigy of himself, silent, motionless. He was impervious to the explanations of General Robert Eichelberger about those conditions; he never stirred himself to examine the ground; he barely spoke to the Australian General Thomas Blamey whose troops did the foul work; he seems almost to have been in denial that it was happening. For MacArthur to sit quietly for hours on end was extraordinary because he was usually a restless pacer, either on his own, thinking, or with a retinue of subordinates. In fact his office space was chosen to allow him to pace, as was his accommodation. For him to be sympathetic and attentive would have made no difference whatsoever to the ordeal that had to be endured, but it would have been human.

This is the first of two parts.

I read this book in my Presidents Reading on the grounds that MacArthur, like Eisenhower after him, had many supporters who pushed him as a candidate, first in 1944 and again in 1952 after President Harry Truman dismissed him.

Skip to content