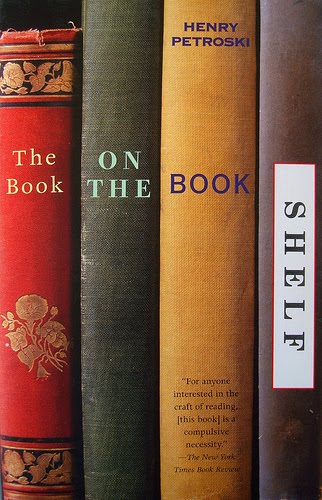

A book about the bookshelf and, more importantly, how bookshelves and books interacted and evolved by a civil engineer. It starts from papyrus scrolls and ends with the e-book which in 1999 was referred to as the Overbook.

As Books Bagshaw once said ‘Books do furnish a room.’ English Prime Minister William Gladstone seriously demonstrated that two-thirds of a gentleman’s home should be dedicated to books. He was thinking of about 25,000 books. Yes, 25,000! (If Books Bagshaw is unknown, show some initiative and find out who he is.)

There was much to learn as books and the shelves that store them progressed through history.

In the 15th and 16th entries books were often sold as loose leafs which the purchaser then had bound, either at the place of purchase or back home in the castle.

In the medieval and early Renaissance Europe context books were precious.

There were traveling book cases, useful to be able to pick up the collection and move when the bad guys came, be they royal agents looking for booty to steal, ahem, taxes, brigands looking for loot, a foraging army in the Thirty Years or One Hundred Years Wars.

These shelf-boxes were often designed to press the books within when closed. Book presses. In time individual books might have a lock on the cover or a hasp with a strap. With parchment books, moisture was the enemy and the books presses, in boxes, straps, or locks were designed to pressed the pages together to exclude moisture. Though over time books pressed would deteriorate anyway. These boxes often had three locks taking three quite different keys held by three different individuals. That is even more distributed security that the firing pin on a nuclear armed Polaris missile on a U.S. Navy submarine. They have only two keys.

Henry Petroski

From these boxes we get the armoire, and the linen press.

It came to pass that bound books were shelved vertically. Who started that is lost in time, but it was a revolution that led to more revolutions.

At first the spine of the bound book faced inward on the self for several hundred years. It often accommodated a metal hasp which held a chain, the other end of which attached to a rod bolted to the furniture. This is the chained library such as the one I saw in Avila. A reader consulted the book right there as the chain was short. The lectern beneath the shelf served the reader with its angled face and foot to keep the book stable. From this evolved the lectern in the front of the class room. The books were chained, as all librarians immediately understand: to keep readers from nicking them!

On those very rare occasions when a chained book was freed, say to be lent to another monastery, it was a major effort to uncouple it from the iron bar that might have twenty (20) other books attached to it. The bar itself was held in place by a lock, which often took more than one key to open as above.

Then there was the question of light. First candle light, then windows, then electric lights. In the early 20th Century glass floor tiles to diffuse the light had a fashion. Light was also an enemy when the inks and dyes were organic, yet it was also necessary so great efforts were made to find a balance.

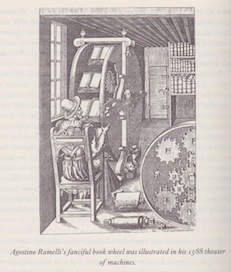

Petroski compiled many drawings, wood cuts, plates, paintings, and other illustrations to show the evolution of the storage and use of books in Europe which edify and amuse. My favorite is the book wheel. It has been literally true for some readers of my acquaintance who always (claimed to) read many books at once and beyond the literal, more importantly, it is a metaphor for the life of a reader like me.

When books became cheaper and thus less valuable, the chains came off. That made it possible to turn the binding outward, and in time the title was printed on the spine, in Britain reading up and then in the United States, thanks to Ben Franklin, reading down.

George Orwell said that ‘People write books they cannot find on library shelves.’ Nowadays we scholars write book no one is looking for.

One of the pleasures of the book is seeing mention made of many libraries I have visited, like Widener at Harvard, the Bibliothèque National in Paris, the Library of Congress, the British Library, the New York City Public Library, the Bodelian at Oxford, Firestone at Princeton, the Hoover Library at Stanford, and so on.

The book ends with an whimsical appendix on methods to order books on bookshelves in a private collection. Each of the 20 or so methods Petroski enumerates has drawbacks that require an arbitrary rule apart from the method. For example, if the method is alphabetical by the author’s last name, the pitfalls come quickly. Is ‘O’Henry’ with the ‘Os” or it is “Henry, O’ with the ‘Hs” and if that hurdle is past what do we do with pseudonyms. Then there are multiple authors and so on. O’Henry was William Porter by name.

By the way, the Overbook is the Kindle today.

This gem was unearthed in the process of sorting and cataloguing books at home. I am pretty sure I have his great book The Pencil (1990) somewhere.

Skip to content