Two American presidents have not been presidents of the United States. I have read a biography of one, Sam Houston, who served two terms as president of Texas when it was a sovereign state. The time came to read of the other, Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederate States of America from 1861-1865. It is an unique story and this is an odd book.

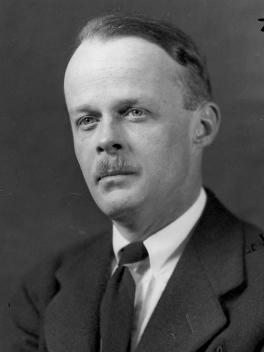

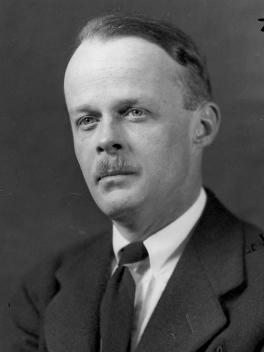

Allen Tate (1899-1979) has a commendable reputation as a poet; he was Poet Laureate of the United States for a time. When I looked for a biography on Davis I recognized Tate’s name (a faint residue from the 8:00 a.m. Saturday morning course I did in college on American Poetry with Dr. Hardwick). That seemed as a good a criterion of choice as any. The book is dazzlingly to read, the words flow, the images are powerful, the rhythm is palpable. It is far better written than Carl Sandberg’s ‘Lincoln,’ he being another poet of note. Moreover, Tate is no apologist for Davis. His strengths and weaknesses are exposed, examined, evaluated, and summarized. To these I now turn, leaving further comment on the book to the end.

Allen Tate (1899-1979) has a commendable reputation as a poet; he was Poet Laureate of the United States for a time. When I looked for a biography on Davis I recognized Tate’s name (a faint residue from the 8:00 a.m. Saturday morning course I did in college on American Poetry with Dr. Hardwick). That seemed as a good a criterion of choice as any. The book is dazzlingly to read, the words flow, the images are powerful, the rhythm is palpable. It is far better written than Carl Sandberg’s ‘Lincoln,’ he being another poet of note. Moreover, Tate is no apologist for Davis. His strengths and weaknesses are exposed, examined, evaluated, and summarized. To these I now turn, leaving further comment on the book to the end.

Davis had an easy life. His father sent him to the best schools, and then West Point, where Davis was an indifferent student, on a merit list 40 out of 60. Davis served in the army in the Wisconsin and then Iowa territory, where he formed a very high opinion of his own military capacity, to judge from his letters. In the Mexican War of 1846 he served with distinction, which he took as further proof of his genius, though in each case Tate suggests others did the heavy lifting, Davis just arrived in time to accept the accolades.

He married, and seemed destined to disappear into Mississippi plantation life, but both bride and groom fell prey to typhus on honeymoon in New Orleans, and his bride, whom he had courted for one year, died within six weeks. He gradually recovered, though he remained dyspeptic thereafter, being stunned and stunted. For the first and only time in his life he became bookish and read in a study all hours, becoming the worst sort of know-it-all autodidact.

His older brother who had, by primogeniture, inherited the paternal planation, took him in, coaxed him back to life by propelling him into politics. Davis won a seat, another indication of his genius, never mind that the opponent was a numbskull, and his brother had arranged for a great deal of support. On he went, each time without much effort on his part, to the House of Representatives, and then the Senate, in Washington. He spoke well, cut a good figure, and his distant manner set him apart. He had by this time re-married, his brother having introduced him to every eligible woman in three states, and seemed contented.

To bring geographic balance to cabinet, and to make way for another to hold that Senate seat, President Franklin Pierce in 1853 appointed him Secretary of War, where he proved himself to be a micro-manager.

He was an exact contemporary of Abraham Lincoln, the two being born within a few miles of each other in Kentucky before their families moved. Whereas, Lincoln had to work, and work hard, perhaps even as hard the legends say, for everything, advantages dropped into Davis’s lap. Tate suggests that Lincoln learned much about working with others and getting along with them, respect for facts, the need to husband resources, modesty, and more, all of which entirely escaped Davis. The Davis in these pages seems born to the priesthood, ready to tell others what to do… Period. Not to persuade, not to sympathize, not to lead by example, not to negotiate. But ever ready to declare. To those who faltered his reaction was scorn and vitriol in equal measure.

He would never rise above himself, his clique, his region, his prejudices to deliver a funeral oration like Lincoln at Gettysburg, nor offer such compassion to mortal enemies as Lincoln in the Second Inaugural. Davis would conclude by some convoluted logic that such speeches impaired his majesty as president, and pandered to the mob for whom his contempt was open. He was never elected to office in the ordinary way. He was appointed to fill a vacancy by death in the House of Representatives. The Mississippi legislature selected him for the Senate twice, thanks to machinations of his brother. As for the Presidency of the Confederate States, read on.

Davis accepted the mother’s milk of states’ rights and took it to be a constant of the universe. Any objection to it was sin to be castigated and cauterised. For all his uncompromising defense of the indefensible, the slavery that was the purpose states’ right, he was not an extremist rushing to war in the manner of Howard Cobb, Robert Rhett, or William Yancey. Indeed when a Mississippi convention voted to secede, he was one of the few to vote against it.

Davis combined a profile among the political elite as an advocate of states’ rights with administrative experience in the War Department and the reputation of a moderate, a combination led him to the Confederate White House. When the leaders of the first six states to secede, those from the deepest South, met in Montgomery Alabama to constitute themselves as a separate sovereign nation they unanimously choose Davis, who had not attended the meeting, to be president. The Fire-eaters who led the secession movement checked each other, and some preferred, consistent with the doctrine of states’ rights, to remain in their state. That left Davis as harmlessly acceptable to all. At this Montgomery convention each state had a single vote, and so Davis won six votes. Surely the smallest vote for any president. As I said above, he had no experience of that fickle beast, the electorate.

When he answered the call of duty for a six-year term, Davis discovered that the Confederate Constitution (modeled on the Articles of Confederation of 1781, hence the name ‘Confederated States’) vested few powers in the President but he determined to make it work. There he exhibited his deficiencies as well as his personal courage and dedication. He worked himself mercilessly at micro-managing the promotion of lieutenants, how ambassadors should be received, and counting blankets. No ambassadors ever came, but had they, he was ready!

His health had been compromised by the typhus and he was fragile, often hors de combat for days at a time.

He was prickly and thin-skinned, unlike Lincoln with that rhinoceros hide. Davis was distracted and apoplectic by any criticism, and often took suggestions and advice as criticisms. Only those who learned to flatter and sugarcoat their approaches enjoyed access and even a modicum of influence with him. Any letter that did not address him as ‘Your Excellency’ was likely to be crumbled up and discarded. When a Confederate general became popular, he was damned in Davis’s eyes as a usurper of the president’s prestige. When a very good proposal came from an individual who had once slighted him, in Davis’s opinion, it was dismissed. When an aide suggested the President show himself in public to bolster civic morale, he was dismissed from service, because Davis took that suggestion to be a criticism and an affront to Presidential dignity. Rigid, inflexible, yes he was. The cause was just, the mob should not be placated but rather chastened to do its duty.

Robert E. Lee is the exception to all of this, and Tate acknowledges that but offers no explanation. He seems to have found it as inexplicable as the reader does.

Tate suggests that in his cloistered autodidact phase after the death of his first wife, Davis read a lot of political science about sovereignty and the divine right of kings, and when the presidency fell, unbidden in his lap, it was the one role model he had, even if unconscious of it.

Much in Tate’s account of the Civil War puts paid to the myth that an external enemy unites people. Not so among the Confederates. The first six states never agreed among themselves, and never deferred to the Richmond government. The second five states likewise. Davis’s cabinet opposed his every move, and he made few enough of them. Here is one example from many, while Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia starved in rags over the winter of 1864-1865 in an agony worse than George Washington’s Continental Army at Valley Forge in 1777, the Governor of Georgia at the end of the railway line from Richmond had 95,000 wool uniforms in storage and three months army rations for 30,000 men. The Georgians in Richmond zealously defended the right of Georgia to retain these provisions though some had been paid for by the Richmond government. Davis would not deign to intercede as it would be beneath his presidential dignity to plead with a state Governor. He did however send him angry letters which made cooperation all the more impossible. No, the Governor did not have an army of 30,000 but he kept the uniforms and rations just the same. That is until Sherman’s Union army found the stores and burned the lot.

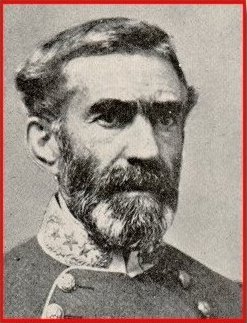

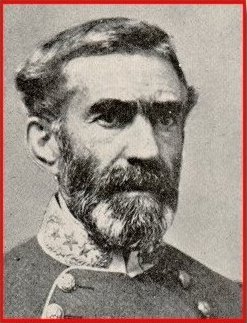

The other example is personal enmity. There was much of it among the politicians and generals, but the most striking embodiment is Confederate General Braxton Bragg whose titanic incompetence made Davis stick to him all the more! Once Davis appointed Bragg, despite the overwhelming evidence of Bragg’s repeated failures, for Davis to replace him would be implicitly to admit he had been mistaken in appointing him, so he did not. Bragg was always careful to address Davis as Your Excellency.

Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg

Bragg thus secured from his own breath-taking errors, devoted himself to undermining his comrades in arms least they succeed where he had failed and show him up, pursuing these personal vendettas even while Atlanta burned. Davis promoted him to higher responsibility from which he continued to destroy the Confederate Army from within. He might almost have been a Union agent. That would explain his actions. As a standard of incompetence, he rivals George McClellan’s stellar achievements. And he had in addition a personal spitefulness and venom McClellan never knew.

Today revisionist historians, searching for a new and provocative and topic, rather than deeper insight, are now rehabilitating Bragg. Mission impossible!

Tate argues that the move of the Confederate capital from Montgomery in the geographic centre of the rebellious states to Richmond was a fatal error that distorted both the military and political strategy that followed. I had never thought of it that way before.

Davis feared ceding a foot of territory to the Union, and so spread Confederate forces very thin, allowing the Union armies to pick off, smaller, isolated garrison one after another. Tate repeatedly disparages Davis’s approach, failing to mention until the last chapter that all the rambunctious Dixie governors wanted it that way and would not have cooperated with the concentration of the army. It reminded me of that spectral Brisbane Line in Australia in 1942. Though the need to concentrate was obvious, it dared not be said, the political trumping the military.

The book is at least half a summary history of the Civil War, and starts with two long chapters that are hard to swallow, blaming everything on the rapacious North and glorifying slavery. No apologist for Davis is Tate but he is a one-eyed apologist for the Slavocracy. Reminded me of the Tea Parody rantings in its profound irrationality.

Believe it or not. I offer no detail, it is too tedious to recount. The result is less of biography than the title promises.

Least a generous spirit excuse Tate for his racism, as of his time and place, note that in the same year that this book was published, 1929, Tate’s fellow Mississippian William Faulkner published ‘The Sound and the Fury’ peopled by thinking, feeling, reasoning blacks wherein Faulkner describes Southern racism as a cancer that is killing black and white, the latter more slowly but just as dead.

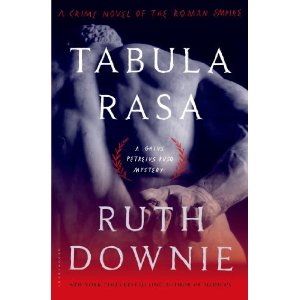

Ruth Downie

Ruth Downie Map of Hadrian’s Wall

Map of Hadrian’s Wall

Allen Tate (1899-1979) has a commendable reputation as a poet; he was Poet Laureate of the United States for a time. When I looked for a biography on Davis I recognized Tate’s name (a faint residue from the 8:00 a.m. Saturday morning course I did in college on American Poetry with Dr. Hardwick). That seemed as a good a criterion of choice as any. The book is dazzlingly to read, the words flow, the images are powerful, the rhythm is palpable. It is far better written than Carl Sandberg’s ‘Lincoln,’ he being another poet of note. Moreover, Tate is no apologist for Davis. His strengths and weaknesses are exposed, examined, evaluated, and summarized. To these I now turn, leaving further comment on the book to the end.

Allen Tate (1899-1979) has a commendable reputation as a poet; he was Poet Laureate of the United States for a time. When I looked for a biography on Davis I recognized Tate’s name (a faint residue from the 8:00 a.m. Saturday morning course I did in college on American Poetry with Dr. Hardwick). That seemed as a good a criterion of choice as any. The book is dazzlingly to read, the words flow, the images are powerful, the rhythm is palpable. It is far better written than Carl Sandberg’s ‘Lincoln,’ he being another poet of note. Moreover, Tate is no apologist for Davis. His strengths and weaknesses are exposed, examined, evaluated, and summarized. To these I now turn, leaving further comment on the book to the end.

Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg

Pavel Kohout

Pavel Kohout

Tsai Ming-liang

Tsai Ming-liang Here she is.

Here she is.