Reading about Jefferson Davis earlier reminded me of his alter ego in the Confederate cabinet, Judah Benjamin, and then a correspondent told me that one of Benjamin’s textbooks from his post war career in the 1880s is still on law school curricula, a fact that I verified easily. In an idle moment – half-time in a Niners game – I looked for a biography and this is the one I found. Published by Free Press, I took that as a mark of quality and acquired it. It is an excellent study with some surprises in it.

What made Benjamin notable in the lackluster Richmond government was first and foremost that he lasted the course of the war and no else did, apart from President Davis himself. As I discovered from reading Allan Tate’s biography of the irascible Davis, Benjamin was one of the very few who somehow got along with that moody, dyspeptic, volatile, and intemperate man. Evans suggests that Benjamin tried all his life to fit in without assimilating or converting to Christianity, though his Judaism was nominal.

Here then was a man who made a lasting contribution to legal knowledge, held very important national executive positions in cabinet for four years, and alone managed to work closely with his president. All in all a singular set of credentials.

Note, the only other person who managed to get along smoothly with Davis was Robert E. Lee, but they seldom met face-to-face, whereas Benjamin saw Davis virtually every day, and of course Lee had his military achievements as a buffer.

First, Benjamin’s background. His family were Sephardic Jews who originated in Portugal and then fled the Inquisition to England. His parents migrated to Charleston in South Carolina (which I visited last year) where Judah was born and grew up. Charleston was a major seaport then and had a sizable Jewish community. His parents were not devout and neither was he, but no one ever let him forget that he was Jewish. It was often thrown in his face, and, if not, then muttered behind his back throughout his life.

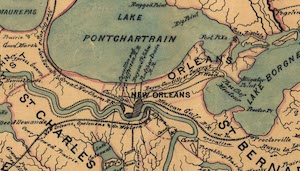

Like so many others, when he was of age, he went west, to New Orleans (NOLA) in the 1820s.

Louisiana had only just become a state. He apprenticed in law and made ends met by tutoring in English while himself learning Creole French. Then as always he had a prodigious appetite for work, and brought to it an organized and systematic mind. He made a tidy sum in NOLA by compiling a guide to the Code Napoléon that formed the basis of the Louisiana law.

It is a complex framework that he distilled, valuable to any law office, but the more so for other English speakers moving to Louisiana and encountering the Code for the first time. In this he demonstrated his eye for the niche where he could do well by doing good à la Ben Franklin.

He married a Creole woman who led him a merry chase for years before and during their marriage. Vexed as that was, it was thanks to her that he travelled to England and France, as well as Spain and Italy. For most of their marriage, she lived in Paris which he visited one month a year. To finance these trips he undertook commercial work in England and France that gave him knowledge and contacts that were an asset later.

In the 1840s the American political party system was fracturing as the old compromises wore thin and the great compromisers (Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, John Calhoun, who preferred compromise to war) passed from the scene and firebrand intractables who preferred war to compromise came to the fore in the North and the South. His legal accomplishments recommended him to NOLA Whigs who got him elected to the state assembly. His appetite for work (and lack of the distractions of a home life) made him their candidate for a Senate seat in Washington D.C. which he won. He lived for a while in Decatur House which stands today. As the Whigs dissolved he changed allegiance to the Democrats.

To step back, just before he ran for the Senate, in the last days of the Millard Fillmore Administration, President Fillmore had to appoint a Southern to the Supreme Court (regional balance then as now was honored) and he offered it to Benjamin. He declined. It was almost hundred more years before a Jew was appointed to the Supreme Court. Class, can you say who that was? Yes, that is right Woodrow Wilson had his beau geste and appointed Louis Brandeis of the Brandeis Brief who was not only a Jew but an innovator!

In the United States Senate Benjamin defended states’ rights but not directly slavery. He became a slave holder when he married and set up house in Louisiana with his errant wife, but had not grown up in a slave holding family. His legal mind, command of precedents, great memory for the dumb things others said, these combined with an assured posture and deep voice earned him a reputation as an orator in the well of the Senate. The important point is that he was a moderate, not a Fire Eater who proclaimed slavery or death like Henry Foote or Thomas Yancey.

When secession started and Davis composed his first cabinet he wanted a geographic spread and he knew Benjamin from the Senate. He offered Benjamin the post of Attorney-General, which he took. At the time it was supposed there was hardly any need for an Attorney-General so his appointment was accepted though his Judaism drew comment in the newspaper.

Benjamin on the Confederate $2 note as Attorney-General.

Benjamin on the Confederate $2 note as Attorney-General.

In the first cabinet meeting in February 1961 he made the only strategic suggestion that comatose body ever conceived. He proposed that the Confederate States government acquire (by purchase or requisition) a million bales of cotton and immediately transport them to England and warehouse them there as surety against future purchases of arms and ships. The proposition died on this lips. What did this short, rotund, Jew who had never served in the army know of war. It would be over the three months. Davis dismissed the proposal in very few words and patted Benjamin on the arm in a typically patronizing way.

That incident aside, Benjamin who had long studied those around him in court to assess the best tactics to use studied Davis, and found ways to make himself indispensable to the cantankerous and thin-skinned Davis.

Whereas the others members of cabinet put as much distance between themselves and Davis as possible, Benjamin took an office next door and socially paid court to Mrs. Varina Davis. He sent her theatre tickets, offered to do things for her children and so on. She soon offered him another point of access to Davis. In the office Benjamin became something like a chief-of-staff who handled the routine, acted as a gatekeeper for those who wanted to see the President, and drafted everything that needed to be written. In a few weeks Davis could not do without him.

When the victory at Manassas was not exploited the incumbent Secretary of War in the Confederate cabinet resigned in a huff and retired to Florida. Since Davis fancied himself a master strategist what he wanted in the War Department, such as it was, was an instrument who would do his bidding. Who better than Benjamin for whom no job was too small or too big. In June 1861 he was appointed Secretary of War, he of no military experience whatever, who had never fired a gun. He did not hunt, duel or any of those like manly arts so common among Southern gentlemen. However, he was a hard working administrator with an eye for detail and a willingness to work with others, qualities rare in Richmond.

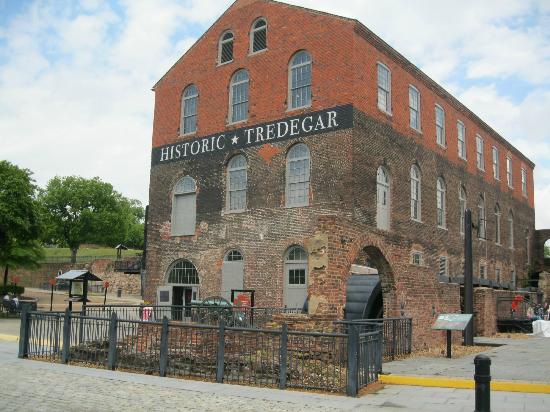

By the way, Evans argues that Richmond would have been the primary target of the war with or without the Confederate government in residence because it possessed the only ironworks sufficient to forge heavy weapons, cannons and shells, in the Tredegar Iron Works.

The Tredegar Works today.

The Tredegar Works today.

In fact, he argues the decision to move the government there had the effect, and perhaps that was the intention, of shielding these iron works with a great army. A point I had never before heard.

The Union anaconda strategy worked and NOLA fell early in the war cutting Benjamin off from his sisters there and his considerable property was confiscated by the Union army. He now was completely isolated in that sense, and Evans suggests that drove him to work even harder for Davis. If Benjamin lost office he could not retire to his home as others who left cabinet had done. His future, if future he had, was now in Richmond.

The winds of war blew more defeats and Benjamin was blamed for them. Evans produces a fascinating correspondence in one instance. Benjamin tells Davis he did not re-supply the Army of Northern Virginia after Antietam because there were no supplies left, no shot, no shell, no horses, no mules, no cannons, no rockets, no men in reserve, no corn, no feed, no salt pork, no nothing and not a gold dollar to buy it. But rather than admit that and (1) undermine civilian and military morale and (2) discourage potential European allies and investors that he would take the blame. Davis agreed to let him be the scapegoat in the newspapers and gossip, which went ballistic in the blame game. Watch the ABC news tonight for an example.

Yet Davis quickly moved to promote him to Secretary of State in late 1862, a post he held to the end in May 1865. Of course the pundits were outraged, Benjamin the Jewish fiend who had no doubt profited from stealing army supplies was rewarded for his perfidy with promotion! That from the Richmond press. But the Confederate Senate approved the appointment because its members knew how indispensable Benjamin was to Davis, even if they did not know about the lack of supplies.

Now Benjamin had a job for his talents. He spoke French and had done commercial law work in England and in France in his travels to his wife who was a favorite at the court of Louis Napoléon. He had many legal and social contacts in both countries. Davis and many others Southerns hoped that England and France would intervene in the war in some way. There is no doubt that it was a tempting proposition. To England it offered the chance to emasculate a commercial rival in New England and perhaps reclaim territory lost in the Revolutionary War. To France it offered the prospect of a Confederate ally to realise Louis Napoléon ambition of colonizing Mexico.

What Benjamin quickly realized that rather than risk a confrontation with the United States, what suited both England and France was to see the Americans in a deadlock. That would serve the purposes of both. England could trade and France could enter Mexico with no reaction from El Norte.

Benjamin went on the offensive. He arranged for Confederate sympathisers to go on public relations tours in both England and France. He paid unscrupulous journalists in those countries to write favorable articles and so on. He directed Confederate ambassadors in each country to offer inducement (bribes) to officials to draw their countries into the conflict.

Given the Union’s naval blockade, making these arrangement was difficult but he found paths through Mexico and Canada, though a letter might take three months to get from Richmond to Paris or London. And many letters did not make it. As a precaution against interception many of his official dispatches were coded and disguised as personal letters from a woman in Canada to a cousin in France, or a businessman in Mexico to a bank in England. In addition, he funded agents in Canada to foment trouble on the border with the United States. He also tried to organize support, financial and recruits, for the Peace and anti-conscription movements in the North, the Copperheads. One example in Vermont features in Howard Mosher’s delightful novel ‘On Kingdom Mountain’ (2008).

In short, he tried everything.

These confections, however ingenious, could not outweigh the realities of blood and iron. The Europeans would let the battlefield decide the matter.

As the military situation produced shortages. the scapegoating of all Jews, but particularly the most visible one, increased in the South. Jews were accused of hoarding commodities, when in reality they had nothing either, he least of all. When a French banker made his way through Mexico to Richmond to negotiate for cotton, he and Benjamin spoke French. Though the resulting contract was very favorable to the Southern cotton interests, it was not enough! The press, the Congress, the know-it-alls, society ladies, men in the ranks all denounced Benjamin for selling out the Confederacy in some invisible way. Why else would a Jew speak French to a monolingual Frenchman but to conspire?

This reasoning is not more stupid than we hear today from many quarters. Nothing is ever enough. The only explanation of a shortfall is personal malfeasance. Sounds like Pox News! Simple minded and loud. Or is that the ABC these days?

The more Benjamin was pilloried, the more he took the only refuge he had, namely Richmond’s small Jewish community. But seen in the company of other Jews only intensified the hostility that good Christians directed at him.

None of this carping influenced President Davis, who was nothing if not stubborn. That stubbornness together with his poor health, he was often bedridden for days and weeks at a time, meant he relied ever more Benjamin who together with Varina tried to conceal Davis’ weakness, least the Confederate Congress start thinking about a new president. Poor health or not Davis made it to 83.

Yes, Class, there was a Vice-President, that tubercular Georgia pygmy Alexander Stephens, who fell out with Davis in Montgomery in 1861 and retired to his home in Atlanta where he stayed until General Sherman came calling. Few people could cope with Davis.

When Davis was laid low by one of his many complaints or was travelling, which he did a couple of times, Benjamin was Acting President in all but name. He called cabinet meetings, he issued directives, replied to letters addressed to Davis and so on. He reported all this to Davis after the fact, and Davis seems to have accepted it. Benjamin often did this work in concert with Varina whose advice he sought and heeded, unlike her husband.

After Gettysburg in July 1863 Benjamin began thinking about a Confederate emancipation of slaves in return for military service (shades of Robert Heinlein’s ‘Starship Troopers’), but he dared not broach the subject with anyone but Varina. Others also realized the dire need for manpower in the army and in 1864 some generals also said the unmentionable, notably Patrick Cleburne, whose reputation as a stalwart soldier was unimpeachable.

Benjamin maneuvered for months to allow Davis to make this bold move and Benjamin enlisted Varina to help persuade Davis, step-by-step, but to no avail. The details are many and best read in book. The larger point is that Benjamin was willing to give up slavery and tried to bring that about, but failed.

A recurrent theme in any book about the Civil War is the Southern dream that somehow it would prevail despite the material odds that favoured the North three or four to one. I tried to pick apart some of reasoning in this list, which is a rough chronology of the progress of the War.

1. Their cause was just and God would see to it, i.e., states’ rights and the white man’s burden of slavery.

2. After the Southern victory at Manassas: They would outfight the Northern city slickers.

3. This dream endured for most of the war: King Cotton was essential to Europe and England would intervene to get it.

4. This, too, surfaced periodically: the English desire to trim commercial rival in New England.

5. In 1863 when Louis Napoléon began interfering in Mexican affairs: French ambitions in Mexico would bring it into the war.

6. Benjamin tried this angle from later 1863: Entice French and English investments which they would then protect.

7. A widely held hope from February 1864: War weariness in the North, Peace Party, anti-conscription riots would change policy and the president.

8. Bruited in 1864 after Lincoln’s re-election. The South would emancipate the slaves and level the moral playing field which would influence European and Northern opinion, the former to intervene and the latter to stop fighting.

9. In March 1865: The Confederacy would recruit soldiers from the slaves with the promise of freedom.

Each of these straws was grasped at one time or another and none bore the weight. England turned to Egypt and India for cotton. Foolish as Louis Napoléon was, he would not act without England.

Louis Napoléon, looking as drug-addled as a celebrity today.

Louis Napoléon, looking as drug-addled as a celebrity today.

He would interfere in Mexico but nothing more. Lincoln won re-election on the Federal army votes. No Southern official would publicly support emancipation, except Benjamin himself. Yes, the Confederate army did accept blacks volunteered to it by their owners to be soldiers in March 1865 but there were only two hundred who were never armed.

The end came in April 1865 and Benjamin fled. The assassination of Lincoln made him a Christ-figure and did not Jews kill Christ. What was Benjamin but a Jew. Worse, some of the agents he had employed were related to one of those implicated in the assassination. That thread would have sufficed to see Benjamin hanged. The yellow Pox press in the North made this connection within days of Lincoln’s death. Lincoln was murdered by a plot hatched by the scheming Jew Benjamin! If it needs to be said, neither Benjamin nor any other Confederate official had any part in the murder of Lincoln.

Benjamin escaped it to England and started a third, or is it a fourth career: Code Napoléon lawyer in New Orleans, United States Senator in Washington D.C., and then Secretary of State of the Confederate States. In England he became a barrister and then a Queen’s counsel. As in Louisiana he found a niche for himself by compiling and publishing in 1868 ‘A Treatise on the Law of Sale of Personal Property, With Reference to the American Decisions, to the French Code, and Civil Law’, which had its most recent edition in 2010 and is still be found in the curriculum of commercial law.

The 2010 edition.

He spent the last years of his life in Liverpool in commercial law, travelling regularly to Paris to see his wife.

The portraits of Benjamin, as those above, invariably show a faint smile on his lips. Even when the Confederate cabinet was in flight, made all the more desperate by the assassination of President Lincoln, Benjamin had that smile. He had frequently been asked why he smiled all the time over the years. His repeated answer was ‘que sera, que sera’ and meanwhile enjoy the moment.

The book is partly a parallel biography of Jefferson Davis in the opening chapters. I had not expected that from the title and even in retrospect I am not sure it was necessary, though it did reveal to me more of Davis than the Allan Tate biography reviewed earlier. The justification for this emphasis is the close association between the two men for the four years of the Confederate States government. But that is only four years of Benjamin’s seventy-three (73) years. Of course it was these years that led me to read about him.

It is the work of a professional historian, well written and thoroughly researched. It does emphasize the Jewish heritage as indicated in the title. While the Judaism does not seem central to Benjamin’s life it was the inescapable first perception of all he met.