When those who preferred compromise to war passed away, there remained those men of principle who preferred war to compromise.

Stephens had two brushes with the presidency. At one time the Little Giant of Illinois, Stephen Douglas, toyed with asking Stephens to be a vice-presidential running mate. Later the Secession Convention in Montgomery Alabama selected him to be Vice-President of the Confederate States. Indeed, he had even been mentioned as a president in the first days at Montgomery before Davis emerged as the preferred candidate.

Alexander Stephens (1812-1883), after a career in law, was a state legislator and member of the United States House of Representatives, where he was embroiled in the collapse of the Missouri Compromise, the Compromise of 1850, the Kansas Jayhawk War, the continuous crises that led to the Civil War.

Stephens in 1855

Stephens in 1855

In his own mind Stephens was a pillar of virtue, a man of unblemished rectitude, absolutely consistent and forthright, unwavering, and never mistaken. He was also pivotal and influential in all matters he touched. That is his own opinion. He had no self-knowledge, it seems.

Schott shows in this well researched and nicely written book that Stephens was inconsistent, illogical, marginal, and often ignored. That Douglas briefly considered him as a running mate indicated how desperate Douglas was to hold together the Democrats as national party, spanning North and South, and how few Southern moderates there were that he might recruit. That he became Vice-President of the Confederate States is because more important players had contempt for this ‘empty compliment.’ Like most vice-presidents, Stephens found there was little for him to do.

Stephens was barely 5’ 2” tall and never weighed more than 100 pounds. He suffered ill health all of his days, and was often incapacitated for months at a time. He spoke in a shrill and high-pitched voice. Nor was he favoured by appearance. In today’s media he would never make it in politics.

He was a prodigious letter writer, and a finder of legal loopholes that made his legal career, an autodidact, who was as pompous as he was short. He had the intellectual vanity of a PhD.

When Jefferson Davis arrived in Montgomery to accept the presidency, he and Stephens met frequently. In those days, just as the assault of Fort Sumter occurred, Davis proposed a three-man commission North to negotiate a peaceful secession and asked Stephens to head it. Stephens declined because of ill health, he said at the time, and because, he added in hindsight years later, he saw no chance of success. Outliving many rivals, Stephens added much hindsight to his record; the the author does a good job of evaluating that hindsight against reality, seldom to Stephens’s credit.

While Davis and others argued that secession was a right to reconstitute a government, unconsciously aping John Locke, Stephens, ever in love with the sound of his own voice, delivered a paean on the divine justice of black slavery in his infamous Cornerstone Speech. That speech, widely reported and reprinted, lit a fire in the abolitionists of the North; even if Abraham Lincoln had been inclined to entertain the Davis peace commission that speech made it impossible. Stephens, the Vice-President of the Confederate States said that the purpose of secession was to defend slavery! He said further that it was a God-given right to enslave others. Moreover, that speech registered with the European powers Davis had been trying to convince to support the Confederate cause.

The author implies that Stephens’s speech was not intended to set a policy, but simply that when he started talking and mentioned slavery, the audience cheered, so he laid it on to milk more cheers from the audience. The author leaves little doubt that Stephens often talked without thinking. Before the death tolls mounted crowds North and South cheered all manner of claptrap. Don’t know what ‘claptrap’ is. Think Tea Party. Got it? Got it!

The Montgomery convention established a provisional government on the condition that the president be elected in one year. The critics of Jefferson Davis were legion. Some things never change and every newspaper editor in the South knew better than Davis how to conduct the government and wage a war, and said so often and in 30-point type. Even so, there were no other candidates; Davis (and with him Stephens) were re-elected unanimously. I cannot find out any more about this election from Wikipedia. There seems to have a popular vote of some kind and an electoral college vote.

What a utopia it would be if we were governed by the philosopher-journalists of the media who know everything.

He and Davis were much alike in their overweening egotism and thin skin, and when the government moved to Richmond, Davis no longer consulted Stephens. Accordingly, Stephens went home and spent most of the war in Georgia, and Georgia contributed as little to the war as possible.

Some historians say that Georgia made war on the Confederate government in the name of states’ rights. Georgia withheld men and material from the Richmond government on a significant scale. It stymied efforts to raise money with Georgia cotton and refused to cooperate with the Confederate Navy’s efforts to run the Union blockade, all in the name of states’ rights. Georgia Governor Joseph Brown won over Stephens with transparent and superficial flattery who then joined him in attacking his own government. Stephens could see no inconsistency in this behaviour. He never considered resigning, but continued to enjoy the status of being ‘Mr. Vice-President’ while disloyally opposing that government he formally served.

The Northern press fastened onto to this show of disunity with glee. European diplomats took note of this disunity, too.

The Confederate Constitution followed that of the United States very closely. It differed, however, in giving cabinet secretaries a seat of the House of Representatives where they would be subject to scrutiny. Schott accepts without examination Stephens’s claim to making this innovation, but the balance of evidence gives that honour to Judah Benjamin, the Attorney-General. (Benjamin had seen this practice in his travels to England.) In the event it seems not to have had any impact and it did not last since most cabinet secretaries stayed as far away from Jefferson Davis as possible by leaving Richmond.

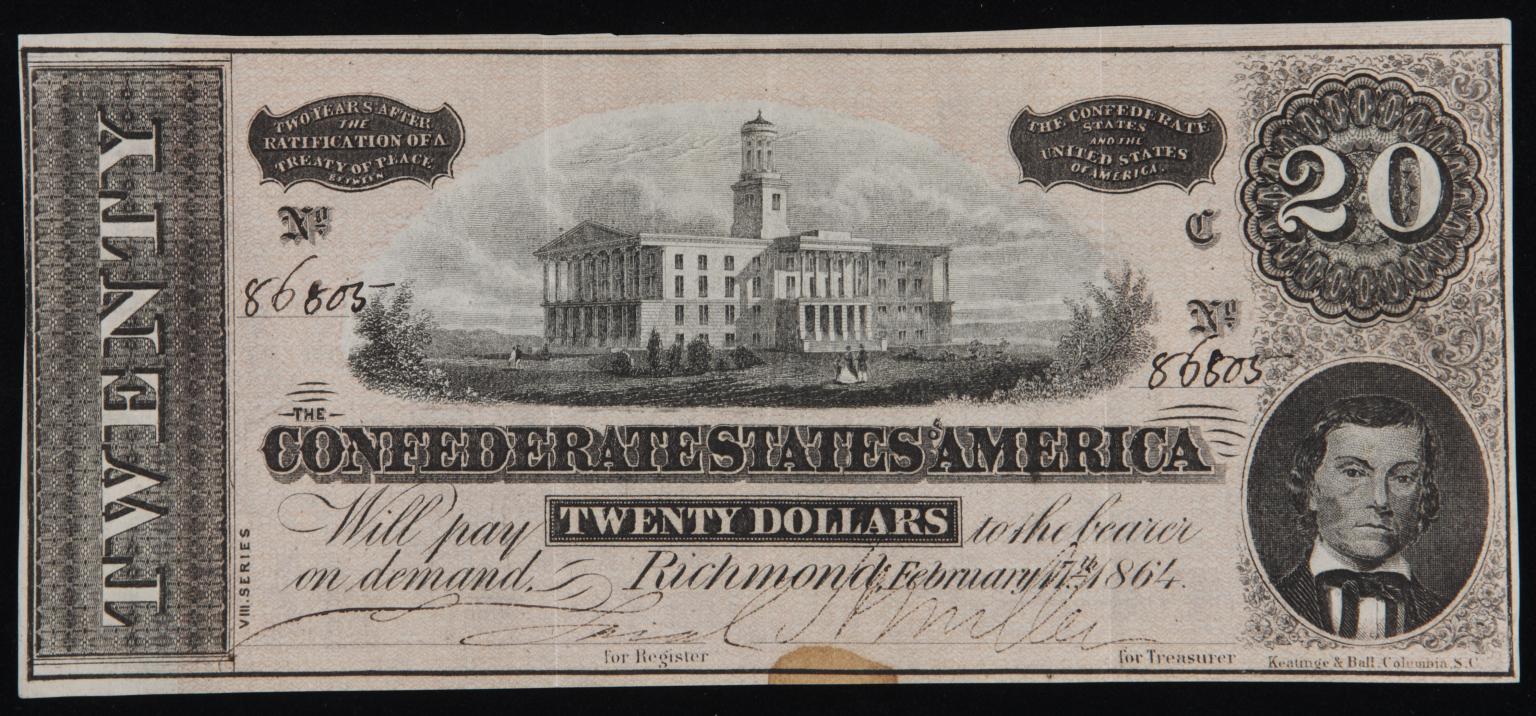

Stephens on the Confederate $20 note which in 1964 would have bought a toothpick. The Confederate government printed about $1 billion dollars in notes, and most of the Southern states also issued their own script, then there were the bonds. In addition to inflation at the time, another result is that they have little value to collectors because there are so many of them. (Readers may remember that in the 1950s the judge in Carson McCullers’s ‘Clock without Hands’ had a stash of these notes which he proposed to put back into circulation to solve the economic problems of the day.)

Stephens on the Confederate $20 note which in 1964 would have bought a toothpick. The Confederate government printed about $1 billion dollars in notes, and most of the Southern states also issued their own script, then there were the bonds. In addition to inflation at the time, another result is that they have little value to collectors because there are so many of them. (Readers may remember that in the 1950s the judge in Carson McCullers’s ‘Clock without Hands’ had a stash of these notes which he proposed to put back into circulation to solve the economic problems of the day.)

Stephens never married and women are rarely mentioned in his extensive correspondence. He would say that he gave himself wholly to his country as a patriot. Did I say ‘pompous’?

While he fancied himself the only Christian gentlemen the country he did not attend church, though he read the Scriptures, and none of his opponents ever threw that in his face on the stump. Odd that. But he was not alone, e.g., Andrew Jackson.

Stephens’s political career started as a Whig, as did Abraham Lincoln’s. They sat together in the Whig caucus in Congress. As the Whig Party collapsed, unable to span the regional divides of North and South and of East and West, Lincoln became the second Republican presidential candidate, while Stephens sided for a time with Stephen Douglas as a Democrat. Class! Who was the first Republican nominee?

A pedant? His first election to the United States House of Representatives was as a member at large from Georgia, which had not yet been divided into Congressional distracts, because its western border was not surveyed. In his first speech in Washington D. C. he declared his own election invalid since the Constitution expressly required Congressional Representatives to be elected by districts of nearly equal size. He was satisfied with the startling effect on the few who heard it and did not act on his own contention, say, by resigning. By the way, the districts were surveyed and in two years he was re-elected from a district.

At the end of the Civil War Stephens was arrested and jailed for four months, the first two were pretty hard but the last two were lax. After his release he was a United States Senators-elect from Georgia but since he had not taken the loyalty oath, he was not allowed to take his seat. Later, after taking the oath, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives for ten (10) years where he served without distinction, and then briefly – less than a year – governor of Georgia.

In this post-bellum years Stephens proved (to his own satisfaction) that he had never erred, that he had opposed slavery, that he upheld the United States Constitution, that he had the right war policy, and more. His capacity for self-delusion had no bounds. That old adage about a person being promoted one level about the level of competence came to mind in his case. In the confusion of wartime, his promotion was several levels above his competence.

The book is meticulously researched and written with a light hand. It gives credit where credit is due to Stephens, e.g., he did visit wounded soldiers in Richmond hospitals now and again, something that Jefferson Davis could never bring himself to do because he thought it was inconsistent with the dignity of his office. After all, one of those hill-billy soldiers might not address him as ‘Your Excellency’, which the only form of address he found suitable for his high station! The book also points out Stephens’s volatility, repeated mistakes, lies, and more.

My one complaint though is that the there is no terminal chapter with a final, overview assessment of Stephens after readers have forced-marched through 520 pages of detail. A bigger picture at the end might give that details some added meaning. Without that picture a lot of that details seems, well, detail for the sake of detail.

A ticket of Douglas and Stephens would have give the wits something to talk about, for example, the Leprechaun ticket or the garden gnome slate at 5’ 6” and 5’ 2” respectively.

Skip to content