It is now commonplace for presidential candidates, even early in pursuit of party nomination, to publish a book. Most of these campaign books are autobiographical of the ‘My Story’ sort. John McCain offered ‘Faith of My Fathers’ (2000) gently reminding readers and reviewers of his sacrifices. Mitt Romney in ‘No Apologies’ (2010) tried to make himself seem ordinary but special at the same time. Barack Obama in ‘The Audacity of Hope’ (2008) and Hillary Clinton in ‘Hard Choices’ (2014) have bowed to the convention. A host of lesser known candidates have had their ghost writers, too, briefly putting their names before the reading public in book stores. (As always, Hillary overachieves and has several other titles to her credit.)

In the current fashion these books emphasise the intangible, the character of the candidate. Seldom do they focus on problems, programs, or goals or have the intellectual content of, say Richard Nixon’s ‘Six Crisis’ (1962).

When the campaign book became an essential is hard to say. Since the 1960s it has become a fixture. Semi-literate candidates who have never read a book, now write one!

In 1936 a campaign book was not commonplace; Long’s ‘My First Day in the White House’ was unusual in its time and place.

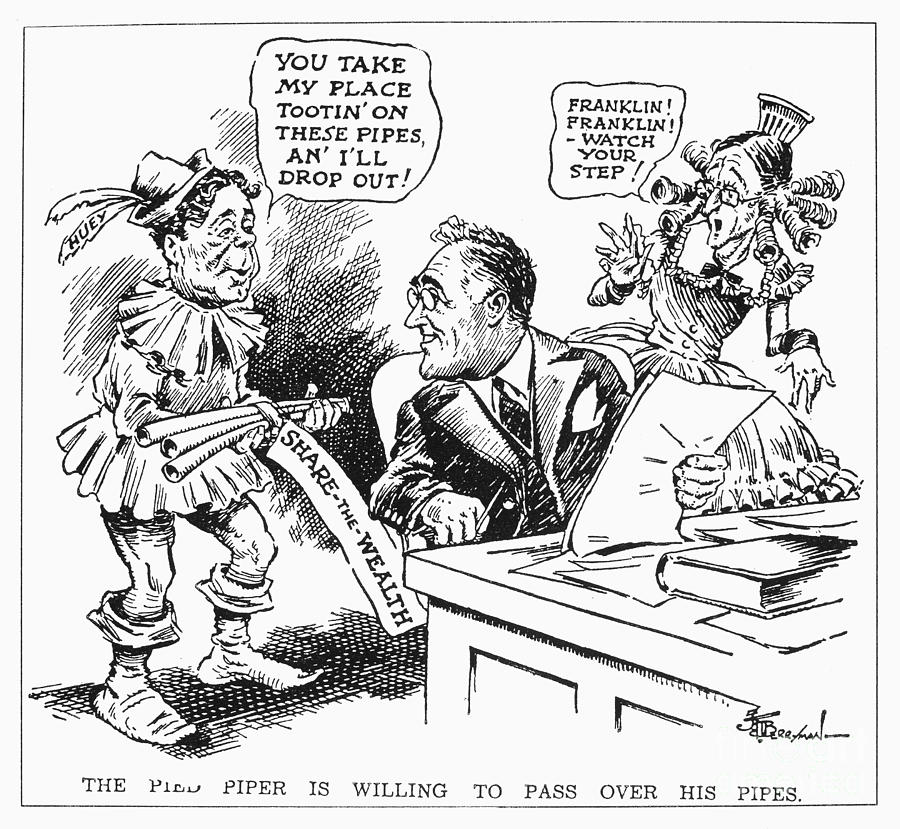

Long’s plan was to support an independent spoiler (Father Coughlin) with no chance of winning in the 1936 campaign to split the Democratic vote and elect a Republican, who would be unable to respond to the Great Depression, leaving the Republicans discredited and the Democrats without a leader by 1940 and the country desperate. Then Huey P. Long would accept a popular draft to take the Democratic nomination. During his short time in the United States Senate Long had begun to organise the spontaneous draft that was supposed later to impel him to the Democratic nomination. Huey never left anything to chance and he worked for the longer term.

This book, incomplete at his death, was a declaration of his intention. The custom at the time was for senators to declare their candidate for a presidential nomination at a press conference in the Senate cloakroom. Never one to follow form, Huey Long did it in this book.

In the hectic life he led, Long dictated this manuscript in 1935 in Washington D.C. where he was a senator from Louisiana, and Baton Rouge in Louisiana where he ran the state through a stand-in governor, often in cars, taxis, and hurrying from one meeting or speech to another, and on the train on his national campaign for his ‘Share our Wealth Clubs.’ He worked 24/7, getting by with four hours sleep most nights.

Long had one simple proposal that the ‘Share our Wealth Clubs’ expressed. Tax the rich! TAX the rich! TAX THE rich! TAX THE RICH! Get it?

It is more than taxing income, by the way, it is was also seizing the fortunes the rich had already amassed. The word ‘confiscation’ was not used but that it what it was. Compared to this spectre, Franklin Roosevelt was a bastion of the establishment.

But what of the book? It has an impish humour that is attractive, and a subtlety of mind and insight into the motivations of others with which he is seldom credited, but which he must surely have had to be as successful as he was. Like many other successful politicians he understood what motivated his opponents and how to manipulate that rather as a sailor learns to tact into the wind.

In these pages President Long hits the ground running, publicly naming a cabinet on inauguration day without bothering to inform those named! It is just what he would have done. He named, among others, Herbert Hoover to Commerce and Franklin Roosevelt to Defense. They could of course decline, but then they would have to explain to public opinion why they refused to serve their country in these roles! Now that is audacity. Needless to say in these pages, they comply with that great god public opinion in the person of its prophet Huey Long.

The millionaires resist but are won over through appeals to their better natures, long term self-interest, and Christian charity. That Baptist ascetic John D. Rockefeller was the first to surrender his fortune to the greater good. His fortune is a pittance compared to J. P. Morgan or John Hill but they, too, succumbed to saviour Long. In short order. Morgan and Rockefeller are redistributing their wealth and ohers’ in a ‘Leviticus’ jubilee.

The only tension is this parable occurs in Chapter Six when an unnamed governor stirs up popular resistance to Long’s initiatives. Long does what Huey Long always did, he goes to face down the crowd, and wins them over. The governor is contrite, saying he led the revolt, to force the Supreme Court to rule on Long’s many initiatives, which it did found and them all good.

The initiatives include nationalising the railroads (calling William McAdoo from retirement to reprise his World War I role as Tsar of the rails), endless funding for agriculture, education, and health, combined with a balanced budget (thanks the confiscation of the fortunes of the Robber Barons). After token resistance, everyone agrees with Long’s vision.

Most of the book is told through dialogue in meetings or letters. There are illustrations he commissioned as the work evolved. This one for example.

There is none of brow-beating, blatant bribing, sale of offices, strong-arm tactics, double-dealing, and threats, or beatings that fuelled his gubernatorial administration in Louisiana in these pages. It is a redeemed Huey that figures here now that he has ascended to the White House.

It is easy to parody the book these generations later, but in the late 1930s with the Dust Bowl suffocating six states, thousands displaced through foreclosure, hundreds of thousands of jobless men wandering the country, hardship without end for a decade, and against the backdrop of President Roosevelt’s tentative first efforts, placed within the organisation of the ‘Share our Wealth Clubs,’ the book would have been a lightning rod for both hope and despair, one that Huey Long would have wielded expertly. Of that there is no doubt.

The book offers a complete social vision, albeit supeficial, as naive and as inspiring as many utopian fictions. It shows the working out of the idea without any of the inevitable reaction, undermining, half-heartedness, and confusion of life. It compares to Edward Bellamy ‘Looking Backward’ (1888) or William Morris’s “News from Nowhere’ (1890).

Skip to content