A krimie set in the heart of Vichy administration in February 1943, a bitter winter in a France without coal, food, oil, wool, or much else. Having just read Robert Paxton’s study ‘Vichy France 1940-1944’ I thought to re-read this title which features some of the historical characters mixed with imagination.

This is the an entry in a long running series featuring Jean-Louis St-Cyr of the Sûreté Nationale and Hermann Köhler of the Geheime Staatspolizei, Gestapo. This odd couple are assigned the most sensitive investigations by either German Occupation or Vichy authorities throughout France after the Defeat (16 June 1940).

It was a France dismembered and divided. Germany annexed Alsace and made Lorraine a special administrative unit an inch short of annexation. The coal and steel producing Nord around Lille was administered from Brussels by Germans. Italians occupied Nice, Corsica, and the Savoy. Finally there was Zone Occupée, the north and west coasts defined as operational areas. Each one of these divisions and dismemberments produced a boundary with checkpoints and rules of exclusion.

That occupation broke the chain of command that had held previously in nearly all of its far-flung colonies and throughout much of the French armed forces, but when the Germans disarmed and dismissed Vichy’s Armistice Army in November 1942, the chain of command broke for military men, too. Many of them now felt free to follow their personal convictions and joined France Libre, especially those in North Africa who had ready access.

To illustrate the internal border controls mentioned above, only 250 letters a day were allowed to pass from the Zone Libre (Vichy) to the Zone Occupée. That is a post of 250 between 40 million people! So strictly was the border between Vichy and Occupied France imposed that even Maréchel Pétain was not permitted to cross it to enter Paris for years. No mail at all was allowed to some amputated parts like Alsace.

By February 1943 the Vichy Regime no longer had a purpose, at least not a French purpose. The Germans continued the fiction because even this hand-puppet government retained enough legitimacy to keep some of the population quiet.

The Vichy establishment had until that November been a Ruritania amid the luxury hotels, the Majestic, Palais, Grand, Prince, and d’Enghien. School desks were set up in the hallways for clerks. Ministerial offices were in suites. Down stairs the thugs from the Garde Mobile provided security, many of them released from pre-war penal sentences.

Prime Minister Laval, the dark prince of Vichy, and President Phillipe Pétain, the figurehead, hated one another. Laval thought Pétain a relic, paralysed by the past, and more interested in breakfast than high politics. Pétain called Laval a peasant, one who blew cigar smoke in his face time and again, preferring as prime minister the austere Darlan or toadying Flandin. Pétain and Laval each plotted the other’s downfall. Laval had traversed the Third Republic, from a Socialist, to a Radical, had been foreign minister, had been prime minister, and came from the Auvergne (Vichy) where he owned a newspaper and radio station. Laval’s powers of self-delusion were so great that he continued to believe in the final victory of German even late in 1944 when most of France had been liberated by the Allies.

It is this same Laval who asks for the service of St-Cyr and Köhler when a young woman is found stabbed to death in the foyer of the long-closed Hall des Sources, the hot springs. This sybarite kingdom was closed in June 1940 and stayed closed since. When St-Cy and Köhler arrive, at 2 a.m., having been summoned from elsewhere, the heat has been off in the Hall for two years and it is freezing outside, yet the hot springs beneath impart warmth to parts of the building, steam vents from pipes broken and not repaired, wherein there is no electricity. As they move about with lanterns, the building seems to breath and even move when images are reflected in the many mirrors , frosted windows, and dull but polished surfaces. Very nicely done.

One such spa

One such spa

St-Cyr has an empathy that allows him nearly to communicate with the dead. He studies the corpse, ear rings, clothing, shoes, feet, hands trying to infer the events the that brought the victim through the snow outside to her death in the locked and abandoned building. Köhler takes a more empirical approach, looking for a lost earring, a boot mark on the base of a counter, recent chip in a beveled edge. The two detectives combine the metaphysical and physical worlds.

Each man served in World War I at Verdun where each was wounded. Both now in the 50s both are too old for military service. Each has been a policing since 1919, and they first met at a police congress in Vienna twenty plus years before. When Köhler was made a one-man flying squad for France, he asked for a French offsider and asked for St-Cyr by name. St-Cyr learned German with his Alsatian relatives, while Köhler learned French in a prisoner of war camp.

Köhler is not a loyal Nazi, still less now that both his sons were killed on the Russian front and his wife left him in the aftermath. St-Cyr sees in Vichy elite many of the embezzlers, opportunists, thugs, and chancers he used to jail. That he works with the Germans, makes him a collabo to many Frenchmen. His wife and child were killed in a bomb blast perhaps meant for him by one of the many factions of the Resistance. ‘Collabo’ is collaborator.

The most venomous French collaborators were the intellectuals in Paris, not the officials and bureaucrats in Vichy, apart from the very top ranks. The collabo Parisienne intellectuals, journalists, academics poured venom on Vichy for its trepidation, its hesitations, its half-hearted pursuit of Jews, its failure to seek out spies in its midst, and so on and on. No exaggeration was enough. No cause too trivial to unleash a torrent of bile. Whoops! Starting to sound like Fox News or The Australian newspaper.

What does the title ‘Flykiller’ mean? Good question! Go to the head of the class. That very question is asked in the book, but not answered. ‘Tue-mouches’ is a code name used by Prime Minister Pierre Laval. In an end note it seems ‘Tue-mouches’ was the code name for Jean Schellnenberger, arrested, tortured, and shot by the Milice in Dijon in 1942.

It is a complicated story with wheels within wheels and more, but finally satisfying. Many blue herrings are followed. A gallery of innocent and guilty ones are reviewed to find the culprit, the Flykiller. The period and place details is credible as is the language. But having said that Jane taxes the reader a lot by seldom clearly signaling who is speaking. Worse since much is thought and not said, in this time when words killed, it is sometimes not clear whose thoughts are on the page. I do wish he learned it write ‘St-Cyr thought’ or ‘Hermann said.’ It would speed my reading and comprehension.

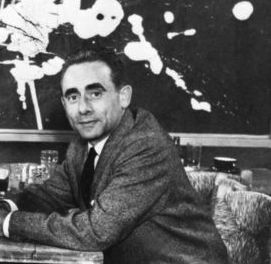

J. Robert Janes

There are a dozen more titles in the series.

Warning! Tangent ahead:

Henri-Georges Clouzot’s (1907-1977) film ‘Le Corbeau’ (1942) is a subtle critique of life in Vichy France made for the German film company Continental in France, and passed by both the German and Vichy censors for national distribution.

Lobby card when the film was re-discovered

Lobby card when the film was re-discovered

The ironies of life are these. In the early 1930s Clouzot worked in Germany for Continental making French version of German films. He was dismissed because he mixed with Jews and spoke against their exclusion from the film industry. He went back to France where he found getting work hard because he was perceived to be a friend of Germany. During the Occupation he found work again with the French branch of Continental making ‘Le Corbeau’ which caused him to be banned from film work from 1945-1947 because the film vilified the French. Upon release the film had been denounced by Vichy reviewers, by reviewers in Resistance newspapers, and by German reviewers, who had it withdrawn.

Henri-Georges Clouzot

He managed to offend everyone in this simple story. Doh! Clouzot’s had tuberculous and, perhaps, had not the strength to explain or defend himself, nor perhaps the inclination. When the ban was lifted he made some memorable films like ‘Quai des Orfèvres’ (1947), ‘Le salaire de peur’ (1953), ‘Les Diaboliques’ (1955). and ‘La Vérité (1960). None of these films fits neatly into a category and so he again irritated reviewers one and all. ‘Quai des Orfèvres’ is a police procedural which is also a study of life in a broken and impoverished France. It does not glorify the police officer nor condemn the villains but treats each as a fact of nature like a thunderstorm. ‘Le salaire de peur’ is an exposition of the nihilism of existential philosophy at a time when most film reviewers were in love with it. ‘Les Diaboliques’, well, these were liberated women without the rhetoric. ‘La Vérité’ is a critique of social hypocrisy among the very people who attend such films. Then there was ‘L’Enfer’, unfinished, a study of obsession though there is a documentary film about it called ‘Henri-Georges Clouzot’s “l’Enfer.”‘ Another Vichy film is ‘L’assassin habit au 21’ (1942) which reduces Vichy to a single rooming house in which one resident is a murderer but which one? It is played as a parody of the murder mystery and so was passed by censors but it irritated reviewers for its failure to conform to stereotypes.

Skip to content