‘Jean?’ who you ask. Jean Monnet (1888-1979). He ought to be called ‘The First European,’ since he is widely regarded as the mid-wife of the European Community. Quite an achievement for someone who never held an elected office and who was never a civil servant. Yet by wit, tenacity, wisdom, patience, a vision, an appetite for data and facts, a network of friends and acquaintances all over the world, he kept moving toward a European union, and he got a lot of other people to move in that direction, too, including Charles de Gaulle.

In 1938 the French Prime Minister sent him on a special diplomatic mission to the Washington D.C. In 1940 Churchill gave him a British passport and sent him on a special diplomatic mission. In 1943 Roosevelt entrusted him to be his representative in Algiers.

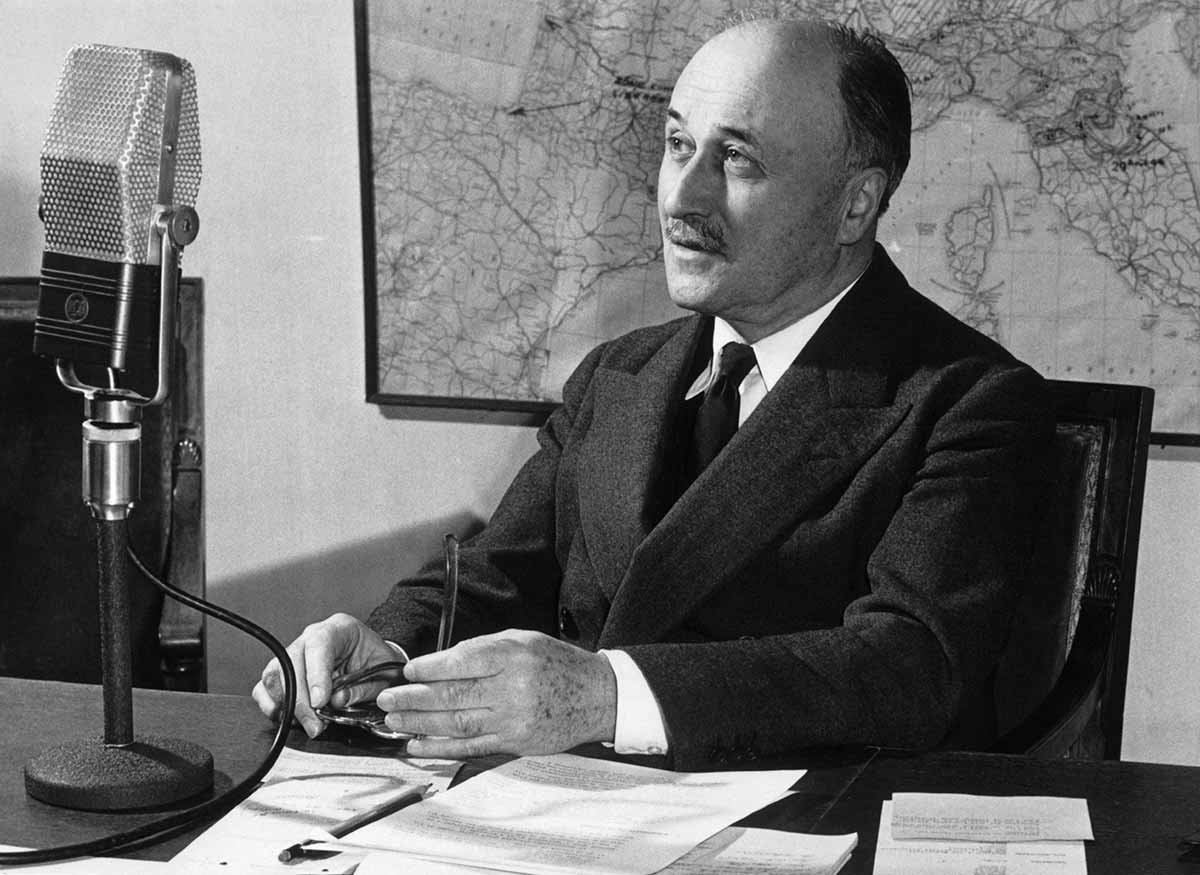

Monnet in Algiers in 1943

Monnet in Algiers in 1943

Internationalist indeed. This was just the beginning.

In Monnet’s mind European union was the means to the bring of enduring peace to Europe. He was born into a wine family in the Cognac and began working for the family company at 16. At that age he learned enough German to sell barrels of brandy to German buyers. Later as his father innovated and expanded the business, he sent young Jean to London to learn English while selling brandy. There he found his best single customer to be the Hudson’s Bay Company of Canada which bought in volume for national distribution. In time the Bay hired him, with his father’s encouragement, and he spent time in Canada, and from there the United States.

Asthma kept him out of the army in World War I, but, inspired by his experience with the Hudson’s Bay Company, he proposed to the French government that it join with Britain in a consortium to purchase not just war materiel but everything else, too, including the shipping to transport it, and the bank loans to pay for it all. An Inter-Allied Committee evolved out of this suggestion and Monnet was its executive assistant, and in no time at all he ran it in everything but name. There were many conflicts on this committee and Monnet was the one who never gave up, who stroked egos, who broke the conflicts down into a small pieces to find common ground, who developed the spreadsheets to demonstrate the priorities…. This committee was successful beyond anyone’s expectations. By the way, it was a small committee of four (USA, England, France, and Italy) and that was another enduring lesson. Keep executive committees small.

Toward the end of the war he left that committee and worked for Herbert Hoover in war relief for Belgium and France in that Herculean effort where twenty hour days were the norm.

At the end of World War I he went to work at the League of Nations, serving there for three years as an international public servant. He passes through Frank Moorhouse’s superb novel ‘Grand Days’ set in the League.

Lured by the business opportunities offered by friends in the United States he moved there and made millions of dollars only to lose it all, as did so many others, in the Great Depression. He went from multi-millionaire to pauper in a few weeks. His passage back to France was paid by friends, including John Foster Dulles.

Never one to sit idle, back in France he received an offer from Chiang Kai-shek’s government in

China to set up and import-export bank in Shanghai. One of his League of Nations colleagues had recommended him for the job. He took it and succeeded, where several others had already failed. Later a dynastic power play in Madam Chiang’s family pushed his patron out of the bank and Monnet with him. His greatest achievement in this venture had been to convince the Chiang government that it had to re-pay all outstanding debts before trying to borrow more. This was a hard sell and it took a couple of years. He also made quite a profit from the three years he spent there.

He married an Italian woman who had left her husband. No divorce was possible in Catholic Europe. Both Monnet and his wife-to-be became Soviet citizens because divorce and re-marriage there was easy. She travelled from Switzerland to Moscow and he from Shanghai and there she divorced her husband and married Monnet. Reds! How did he live that down in the Cold War? This book sheds no light on that.

When he returned to Europe Monnet hatched a plan for France to buy airplanes from Canada. These airplanes would be assembled in Montréal from airframes and engines manufactured in the United States, in a work-around of its policy of neutrality. In the course of devising this plan Monnet had private meetings with President Roosevelt at Hyde Park.

The French capitulation occurred before those planes were delivered, 5000 in all, but Monnet on his own responsibility signed them over to Great Britain. For this act, and many later ones, the Vichy French regime charged him as a traitor. De Gaulle did the same, by the way, with military equipment intended for the French army in 1940: Gave it to Britain.

Churchill’s desperate gesture to keep France in the war in May 1940 after Dunkirk was to create a union government combining France and Great Britain as one. Churchill offered to defer to Paul Reynaud as the head of such a government. Quel beau geste! In London Monnet wrote the text for Churchill. The idea was that then Reynaud could take the government out of France to London and the French fleet and France’s considerable colonial army could be brought into the war. Reynaud could not convince his cabinet to continue the struggle and the moment passed.

Though Monnet supported de Gaulle’s effort to keep France in the war, he feared basing it in London would compromise it in the eyes of Frenchmen, which it did. He tried to convince de Gaulle to move to Algiers, and so remain on French soil. De Gaulle did not, and probably wisely. To move Free France to Algeria in 1940 or even 1941 might have meant capture by Vichy. Moreover, even if Algiers could be won over, location there would mean foregoing the material support Great Britain offered in London.

In 1943 Monnet was thinking ahead about European reconstruction. In Washington he used his business and political contacts to talk incessantly about the necessity of economic reconstruction to ensure social stability, including one lunch at the Pentagon with George Marshall. Monnet was responsible for American Lend-Lease supplies going to Free France. In fact, at the times he was the de facto American administrator of Lend-Lease going to Free France, and the de jure French manager of the supplies obtained. In this role he was a tyrant for propriety, insuring there was no hint of the graft, corruption, or profiteering that marked so many Lend-Lease operations elsewhere. This propriety made later Marshall Plan funding easier to justify.

Explaining the Coal and Steel treaty

Explaining the Coal and Steel treaty

The historic conflicts between France and Germany, in the industrial age, had focussed on the Saar, Ruhr, Pas de Calais, Alsace, and Lorraine because there is where the coal and steel was. In 1943 Monnet was drafting plans to internationalise these regions under joint control of three or four countries. This is the seed of the European Coal and Steel Community, which later gave birth to the European Community. Monnet’s idea was to take the means of modern war out of the hands of a single country to put them into some kind of transparent international protectorate.

He was the author of the Schumann Plan that embodied this ambition and led to ever greater French and German collaboration and European unity. It was not easy going, and it took nine complete versions to get a plan that both France and Germany accepted since it involved a diminution of sovereignty. While others gave up and quit, Monnet persevered. The European Coal and Steel Community became the first voluntary European entity since the Holy Roman Empire. I omit the League of Nations because of its origins in Woodrow Wilson’s insistence on it as the price for the Treaty of Versailles to end World War I.

With Robert Schumann, foreign minister, selling the big idea.

With Robert Schumann, foreign minister, selling the big idea.

No sooner was the ink dry on the Treaty of Rome in 1957 which marked the beginning of the European Common Market, European Community, European Union of today, than Monnet began to talk about financial integration. He set up an Action Committee of private citizens, partly funded by foundation (including Ford and Rockefeller) grants, to organise seminars, radio lectures, publish discussion papers on financial integration, brief journalists which in time came to be a common currency, the Euro.

As successful as he was, Monnet had failures. Try though he might, he could not convince Roosevelt to recognise de Gaulle’s Free France as the provisional government of France in 1943.

Monnet also proposed a European army, partly motivated by the Soviet Union’s machinations at the time of the Korean War. This, too, failed. His aim was to contain German re-armament within such a pan-European army.

Another failure was Euratom which he proposed to make nuclear research European and so not put to military use by a single nation. France itself would not agree to this limitation, though the initiative is in the genealogy of CERN in Geneva today.

How did Monnet do all of this? Most of all he was a salesman. He loved big ideas and no idea was too big to interest him. He did not think of reasons why a big idea was impossible. As he emerges in this book, he is not reflective, nor introspective, and certainly not given to self-doubts. The harder the sell the more energised he seems to have been. He was not a writer either. The many policy proposals and discussion papers were terse, and detailed in dot points, graphs, tables, maps, and charts. The text would be filled out later by others. His preferred method of exposition was discussion and he was a master of that whether in a seminar, at the podium, dinner table, or a seat on a train or plane. Every occasion was used to develop, test, and advance the big ideas.

How did he live? Often he was sustained by the grace and favour of friends and admirers. He had no fortune and long ago he had signed over his share of the family business to his brothers. The money he made in China was considerable but moving in the elite circles he did meant the best restaurants, the best hotels, first class passage on ships and planes. He exhausted that money soon enough. His service on one special mission after another, yielded living allowances and nothing more. When at 70 he slowed down, to live on …. a pension derived from his three years at the European Coal and Steel Commission and that is all. He agreed to write memoirs in return for a hefty advance which supported his last years.

His name is everywhere in Europe. On postage stamps, commerative medals, universities, think tanks, government fellowships, busts and plaques in foyers of EU buildings in Geneva, Brussels, and Strasbourg, and the like, and yet he remains largely unknown, ever the stage manager in the back while the stars tread the boards before the audience of history. Indeed his name can also be found in Australian universities and yet few could say more than a sentence about him.

Monnet cognac remains in the market though no member of the family is now associated with it.

The book is comprehensive and thorough with admirable documentation. It is far more interesting than the first biography of Monnet I tried to read. Perhaps because Monnet was not a leader and did not hold an office, there seems to be little drama or momentum in the book. To confess, as fascinating as the story is, I found it a test of will to finish reading it.

Aside: Roosevelt’s handing of all things French in the war seems to have been clumsy and ill-informed for such a master juggler. Roosevelt overrode his Secretary of State to maintain diplomatic relations with Vichy from July 1940 to November 1942. Roosevelt’s hand picked ambassador to Vichy recommended suspending diplomatic relations but FDR ignored this advice. Did Roosevelt hope that indulging Vichy would make things easier when the landings in Morocco occurred? It did not. Vichy ordered resistance and resistance there was. Ditto in Algeria. In Algeria the United States through diplomat Robert Murphy indulged the Vichy governor Admiral Darlan and tried to undermine de Gaulle. Darlan enforced Vichy’s anti-Semitic laws, arrested and deported to France enemies of Vichy, transported Jews to France for German death camps, and more while America officials and officers looked on. Even though by that time it was clear Vichy would not, could not open any doors to France when the invasion came to the continent.

Skip to content