In 1931 the French army was the largest, best trained, most modern in equipment with a wealth of strategic intelligence in a large and able general staff joined to the leading airforce of Europe and a large navy with newer and more powerful warships than England or Italy. In addition the French Army had those kilometres and kilometres of tunnels, bunkers, turrets, gun emplacements, tank traps, endless buried telephone wires and underground cities of the Maginot Line. To members of the general staff of Germany, of Spain, of England, and of Italy, France was an impregnable fortress. Moreover, it had an even larger colonial army spread around the globe from New Caledonia to the Caribbean. In particular its officer corps was its pride. It was drawn from all classes of society, promoted on merit in a system that prized intellect.

It was altogether impressive, this army, and yet less than a decade later during five weeks in May 1940 this army was comprehensively defeated. So total was the defeat that it was embarrassing. The defeat was as much psychological as material. French troops fought with each other in the rush to surrender. Units far from the front abandoned their arms never to touch them again because of rumours of a truce before the first radio broadcast of a ceasefire. Officers, it was said, surrendered as quickly as possible so as not to miss lunch. Censors tried but failed to suppress pictures of lone Germans herding thousands of apparently willing French prisoners along. This moral collapse turned the army into a mob by the thousands. When the German burst from the impassable Ardenne forrest, the French army fell to backbiting and backstabbing at all ranks. For their part staff officers in Paris denied responsibility and knowledge of anything and everything in some squalid episodes.

The surrender. General Gerd Von Rundstedt went on and on reading a long statement authored by Hitler to the French officers. There are many videos of this ceremony on You Tube.

The surrender. General Gerd Von Rundstedt went on and on reading a long statement authored by Hitler to the French officers. There are many videos of this ceremony on You Tube.

Yet apart from some volcanic fighting in Belgium and around the Pas de Calais (Dunkirk and Ostend), the defeat resulted in relatively few French casualties, making it all the more surprising, and all the more embarrassing. In fact, French Army emerged from the defeat largely intact, though its members were divided, dazed, confused, isolated, dispirited, and exhausted. There is plenty of newsreel footage on You Tube. Have look.

Perhaps the analogy is to victims of a mighty car pile-up on an expressway.

A poilu dazed, stunned, isolated.

A poilu dazed, stunned, isolated.

Blind-sided, a gigantic wallop with noise and shrapnel, and than another and another as the pile up continued. Much noise and confusion but few killed or injured. Yet all are dazed and confused.

This book is a study of how one set of the victims of that crash, the officers of the French army, responded to the catastrophe. It is a subject that takes study, because the recriminations at the time and since have been a blizzard without end, as blame as been laid this way and that, often with no other evidence than the unshakeable conviction of prejudice. In fact, it is perhaps the kind of study best done by an outsider who is disinterested in the matter. This book is based on archival material, publications of the day, interviews with participants, and, inevitably, the river of memoirs protagonists wrote to justify themselves. It is impressive to see how much microfilm of contemporary records and reports in German and French the author worked through to find the confirmation or disconfirmation of assertions that in other books are taken as read. Through this minefield Paxton picks his way with care and sound judgement.

What prompted my interest in this study was the realisation, born of reading about this period, that the chain of command in the French army survived the triple debacle of June 1940 and remained in place for the use of the Vichy regime both France and in the colonies, triple in the defeat, the surrender, and the humiliating peace.

Remember, that this army was deployed around the world in French colonies, territories, protectorates, enclaves, embassies, and missions – most particularly in Africa and the Middle East but also in the Caribbean, India, Latin America, and Oceana, including New Caledonia, today a one hour flight from Brisbane.

As discredited as defeated France was, the colonies held fast to it in this dark hour despite the clarion call from London on 18 June, when Charles de Gaulle made his first radio broadcast in the name of France Libre. Likewise, the officer corps in France also obeyed orders to return to barracks or comply meekly with capture and imprisonment. As German archives show, they were themselves surprised at the speed and scope of the capitulation and unprepared for it.

Even as two million French prisoners of war were being entrained to Germany, the remainder of the French army began to demobilise itself. While de Gaulle shined a light, in the first months few officers followed it. This is all the more remarkable considering the residual anti-German sentiment throughout France and most particularly in the army after the bloodbaths of World War I, which had led to the development the formidable army described at the outset.

One German guard and hundreds of French prisoners bound for slave labour in Germany.

One German guard and hundreds of French prisoners bound for slave labour in Germany.

Paxton’s focus is not on the defeat but the aftermath, though he does set the scene by showing how in the years after 1931 the strength of the army dissipated. There were disputes within the army over strategy and tactics that took the form of bureaucratic backstabbing and career blockage to new extremes. Charles de Gaulle was himself one of the victims of this battle.

Though French tanks and fighter planes were technically superior to their German, Italian, and English counterparts in 1939, the doctrines that dictated their use did not exploit the capacities they had: One example, Renault heavy tanks were technical leaders, and those the Germans captured were later used to good effect on the Russian front in the following years. But French army doctrine spread them very thinly through infantry regiments as mobile block houses for static defence. They were not grouped to give weight and supporting fire power in attack. The Germans, at the time, had lesser and fewer tanks but made far more effective use of them. The same could be said for aircraft. It is also true that often the French forces outnumbered the attacking Germans, but the tactics of the Germans with tanks and aircraft overcame the numerical advantage the French had. The French also enjoyed the advantage of shorter and interior lines of communication but again German tactics cut these by attacking roads and bridges from the air. The French airforce doctrine conserved assets and did not attack German ground targets.

Even more corrosive were social attitudes of those born to the army, and their scorn for parvenus, including Jews that had entered the army during the Third Republic, especially under the Popular Front government. It went beyond the usual snobbery or cliques one must expect and included systematic efforts to degrade, discourage, and drive such undesirables out of the army. There were many little Dreyfuses victimised in a hundred small ways for the lack of a ‘de’ in the name or the presence of ‘berg’. Contrary to the post-war legends there was little liberty, equality, or fraternity in the French army by 1939.

After 1931 successive governments cut defence spending, as did General Phillipe Pétain, when he was minister of defence, and cut it again, and again as the Great Depression spread. As the ordeal of World War I receded from memory, an historic anti-militarism in French society, a child of the French Revolution when the army was the instrument of royal oppression (and it was again with the Napoleons and restored monarchs), re-asserted itself. Parliamentarians not only cut military budgets but they boasted and bragged about it, including one Pierre Laval. In the name of liberty, conscription was qualified by twenty pages of exemptions and exceptions, while the overall length of service was progressively shortened. A standing, professional army was perceived to be a greater threat to society than a foreign enemy by many ideologues who came to prominence in the Popular Front era of the Third Republic. It is also true that the Communist Party of France, following explicit orders from Moscow, disrupted French defence industries by strikes and sabotage and sheltered those fleeing conscription.

Though French generals said they were ready for war in 1939, despite later denials, the record is clear. It is equally clear that when the German offensive struck they were among the first to show the white flag. To review the last days of the Reynaud government as it fled from Paris, is to conclude that the generals gave up the fight before the politicians did. Prime Minister Reynaud himself was prepared to take the Government into exile and continue the war, as the Dutch, Norwegians, and Danes had done, but the generals, including Pétain advised him to surrender not just the army but the government itself. Reynaud could not bring himself to do that but he bowed to the majority of his cabinet and deferred to Pétain to seek terms of an armistice. Instead Pétain capitulated, precipitating generations of debate about the legitimacy of his initial government.

Later, of course, the generals blamed the politicians, but that is hard to credit. Start with the commander in chief of the field army, Maurice Gamelin, who set up his headquarters in splendid isolation from the front lines in a place chosen more for the wines in its cellar than for its communication or access to the armies he commanded. Read this sentence slowly: After nine (9) months of war, he had in his headquarters no telephone in May 1940.

Maurice Gamelin

Maurice Gamelin

He sent and received messages by car and motorbike along country lanes but few roads ran to the border where the army was emplaced. He later explained his inaction in the crisis by saying that he did not know what was happening. Hmm. If communication with Gamelin was slow when nothing was happening, once the front broke he was a hard man to find. (Radio was too easily intercepted for use and unreliable in the heavily forested area and jammed by Germans.)

I referred to doctrines before. Here is another example. The French General Staff had slowly and painfully negotiated an agreement with Belgium before the war to form a line of defence on the Dyle River in Belgium. This Dyle Plan allowed three (3) weeks, 21 days, for the French Army to take its positions along the River Dyle. Care to guess how long it took Germans to breach that line? Three (3) days. Once that happened the French Army had no plan of operations. They had thought of everything except a Plan B. (By the way the British Expeditionary Force was part of this plan and was thus left without a mission.)

Overarching themes:

Officers from general to lieutenants denied the defeat by blaming politicians, British perfidy, spies, lazy conscripts, unpatriotic civilians….women who smoked, protestants, secular education. The list went on. Only the army was blameless for its defeat.

Military contempt for parliamentarians and the Army’s early effort to dominate the Vichy government. Civilian control was only established in April 1942. Apart from Maréchal Pétain himself the Vichy government was dominated in its first crucial months by General Maxime Weygand and then later for longer periods by his navy rival Admiral François Darlan.

Backstabbing, cliques, career opportunism were rife in the very hard circumstance of the armistice army that the conquering Germans permitted. This personal struggle is most well documented at the most senior levels of the army but it was not confined to the top.

Vichy played off Germany against Britain and vice versa by trying to be neutral, not so much in Vichy France itself, but in the colonies, especially those of strategic import like Dakar, Damascus, Djibouti, Diego Surez, Noumea, Oran, and Bizerte. To keep the Germans out of the colonies the Vichy regime defended them from British incursions. To keep the British from occupying a colony there was the spectre of a German response.

There was an effort to use the National Revolution of Vichy to enhance the status of the army after its humiliation. The new curriculum emphasised patriotism and physical fitness and left little time for science. Girls were encouraged to leave school at puberty.

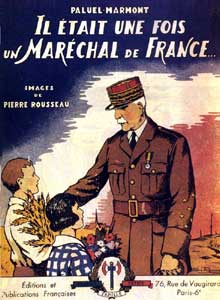

The benign Pétain.

The benign Pétain.

The fate of two million French prisoners of war in Germany preoccupied some officers to the exclusion of everything else and was ignored by many others. These prisoners included all ranks including generals like Giraud, Juin, and others.

Inter-service rivalries that pitted the influence of the army against that of navy, and the navy won very often because it had all those lovely ships which the British wanted and the Germans did not want to Brits to get until November 1942. The army was discredited by its collapse.

The near thoughtless compliance with the purge of Jews from the army, navy, and air force. Likewise the German efforts to identify and seize Germans in the French Foreign Legion is a sorry story of compliance.

Most officers obeyed Vichy because the regime was congenial, not out of duress or desperation. Indeed those officers forcibly retired to reduce the size of the Army clamoured for re-admission.

Vichy officials reluctantly agreed to many German demands but moved slowly to comply. It might take six months to get agreement from them, only to find it was another nine months before they took the first steps. There was a lot of this kind of passive resistance. It is not easy to trace its origin. At times both Pétain and Laval expressed anger at the slow movement of their government, but at other time this pace suited their efforts to keep Germany at the negotiating table.

The Vichy regime presented itself to France and to the world as the sovereign government (of what was left) of France. See, for example, the newsreels at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dU61J_xXBAE

(Cut and paste the address into a browser.)

The army’s chain of command held despite the colossal shocks of May and June 1940. By and large the French army from generals to lieutenants accepted Pétain as the government of France and obeyed his orders. But it is important to realise why that chain held despite the unprecedented jerks on it. (It might have been a different story without Pétain. A government with only Pierre Laval at the top, well that certainly would have been less compelling to most officers.)

Officers had responsibilities; they were not free agents. As long as those responsibilities remained and made sense, they stayed at their stations. Paxton makes this point by analysing the officers who joined de Gaulle’s France Libre. They numbered several hundred and then thousands and invariably they were officers who did not have command of men who were dependent on them.

De Gaulle himself is an example. He had been relieved of his field command in May and appointed an under-secretary for war in the Reynaud cabinet, and then sent back and forth to London several times to gouge greater effort from Britain.

The officers who first joined de Gaulle fell into these categories: retired, on unattached duties (ill or convalescing), attachés at embassies around the world (particularly Latin America), staff officers who did not command subordinates, on special assignments (e.g., as couriers, liaison, or missions abroad). These officers were free(r) agents than those with dependents, i.e., subordinates. They came from metropolitan France but also from the colonial forces. Of course they may have had families to think about, too.

While nearly all officers at French embassies in the the Americas saluted de Gaulle’s flag, not every retired or convalescing officer did. The second criterion that Paxton suggests was decisive is access. Retired or unattached officers who had only to travel a short distance to join de Gaulle, were more likely to do so. Many officers on special assignments were already embedded with British forces as liaison or couriers along with scores of others in the United States and Canada on a variety of missions. Some colonial officers had only to walk across the street to a British consulate to get passage to London. But retired or convalescent officers in Lyons or Metz had no such access and so joining de Gaulle may well have never crossed their minds. Later the fear of reprisals against one’s family in France held some officers in check. Others adopted noms de guerre to avoid such reprisals.

In time as the Vichy regime lost creditability. The unopposed Japanese seizure of Indochina shocked officers far and wide but most of all in Indochina, from which some intrepid souls found a way to abscond and travel, slowly, to England. German setbacks like the stalemate at Stalingrad encouraged others to abandon Vichy neutrality for the opportunity to return to the war effort, e.g., those garrisons in India (a surprising large number). While some officers were staunch themselves they turned a blind eye to the departure of junior officers, forging roll calls to fool German supervisors. Yes, there were German supervisors throughout the French colonial Armistice Army, as well as the Armistice Army in Vichy territory.

Officers in the Armistice Army in Vichy also acted in secret. Rather than turn over all weapons and ammunition to the Germans, they hid much against the future. One trove, scattered in numerous caves, mines, commercial wine cellars, abandoned barns consisted of thirty-nine (39) tanks! The tanks had been disassembled and crated, marked as agricultural material and salted away.

When American troops landed in Morocco and Algeria in November 1942, the veil fell. The Vichy chain of command was by then muddled. Mistrust, suspicion, fear of reprisals from either Germans or Gaullists, residual anti-German feeling, loyalty to Pétain, inter-service rivalries between the navy and the army, tests of will between civilian control and military, all had grown over time and reached new heights; this brew bubbled, collided, mixed, leaked when reality of an Allied invasion occurred.

The velvet gloves come off and panzers roll into Vichy France in November 1942.

The velvet gloves come off and panzers roll into Vichy France in November 1942.

Contradictory orders were issued one after another by a single commander as information came in or was discredited. Conflicting orders came from civilian and military authorities, who then disputed each other’s right to give orders. Generals disputed the authority of other generals to give orders in the crisis. Messages from Vichy said one thing and the local representative of Vichy said another.

Because communication with Vichy was disrupted, the chain of command was altered, but not everyone got the message about the change. Some commanders got orders from generals they had never heard of. Confusion was the result and that led often to inertia and paralysis. Though the reaction of soldiers when attacked is to reply in kind, there was no decisive leadership and the will to resist dissipated within hours. The soup of conflicting orders, contradictory orders, the unabated undermining of rivals confused the matter all the more.

One example is a captain with a company on the beaches at Casablanca received orders from a his colonel to greet the arriving Americans as allies, and almost simultaneously orders from his major to fire on the landing parties. Faced with this contradiction, the captain took his men back to the barracks. The colonel and major were each passing on orders they had received.

In this mire, the castle was Algiers where the headquarters of the French colonial forces in North Africa was located. The conflict and contradictions were played out there with full force. In addition the American sponsored alternative to de Gaulle, Henri Giraud arrived with his immense prestige as a soldier and his childish incomprehension of the political situation, along with the American commander General Mark Clark whose campaign had already fallen behind schedule. In addition, François Darlan, Vichy Minister of Defence and commander in chief of the French navy was in Algiers on private visit to his ill son. The clash of these egos was seismic. The French would not agree among themselves, still less with Clark, but he had the bayonets.

At stake in this opera in Algiers was nearby Tunisia. It was the frontier between Vichy North Africa (and now the Allies) and Rommel’s Afrika Corps in Libya. The Germans wanted to use Bizerte as a port to supply Rommel. Vichy neutrality forbade that. When it became clear that the Allies had taken over in Algiers, and when de Gaulle arrived there and ended the fruitless negotiations with Vichy officials, the Germans stopped asking and started taking. In response the French troops in Tunisia turned on the Germans. As soon as this switch was reported by the Germans to Vichy, Pétain relieved the Tunisian commander, General Alphonse Juin, who ignored the order on the assumption that Pétain’s hand was forced by Germans. The chain of command snapped at long last.

Now the Armistice gloves were off from Morocco to Tunisia and Djibouti, and French officers along with their commands in these stations joined the Allies as speedily as possible. Within a few months every French colony was aligned with France Libre. Thereafter, General Juin’s 100,000+ man First French Army led the way in the Allies’ Italian campaign. At the bitter end, Free France had 250,000 soldiers in the field in Europe.

The necessities of war brought Great Britain and Vichy into conflict to be sure. While Hitler had promised not to seize the French fleet, he was not a man famous for keeping promises. While French admirals swore not to let their ships go, would they be able to resist at the moment of truth or would they, like so many others, be overwhelmed by the Nazis?

Noteworthy, but not mentioned is that the Armistice Army was never used to enforce order in any sense. This army did not round up Jews. It did not kick in doors to arrest trade unionist. Its parades were not designed or intended to intimidate onlookers, in contrast to German parades in France. Rather these parades were intended to boast morale in the ranks and in the viewers.

I do wish the author had included some kind of chronology of major events with a comment on the fallout of each as I did above.

I do wish the author had included more numerical information, i.e., data about the military formations discussed. Numbers are mentioned at times, but a table or graph would be more effective.

I do wish the author had more systematically distinguished the metropolitan Armistice army from the colonial Armistice army, and then offered some general account, complete with tables, of their size and distribution.

Only a few sentence end with conjunctions in this book, however. This regrettable tendency is much in evidence in another Paxton’s books.

Skip to content