Laval was the dark prince of the Vichy Regime (1940-1944).

Pierre Laval in 1931

Formally, he was prime minister while the venerable and elderly General Phillipe Pétain was president. These two hated each other and spent a good deal of effort in undermining one another. Although Pétain was willing to collaborate with the Germans and re-make France into an agricultural nation bound to family and church and reject the Third Republic and end all that liberty, equality, and fraternity rhetoric in favour of work, family, and country, he did draw lines against the Germans. Not so Laval who gave in to German demands at every turn, and at times offered more than the German demanded. He said that he did it to secure the good will of the occupier. There was never any evidence that good will resulted. When the Germans demanded slave labor, disarming the fleet, handing over Jews, Laval complied. Pétain did not.

Laval had entered the national assembly as a Socialist, having had a career as a labor lawyer. There he formed a boundless ambition, and a belief in himself that became delusional. In pursuit of that ambition he moved across the political spectrum to the centre and then the right. In the Third Republic in the 1930s he was a foreign minister, interior minister, and prime minister at one time or another.

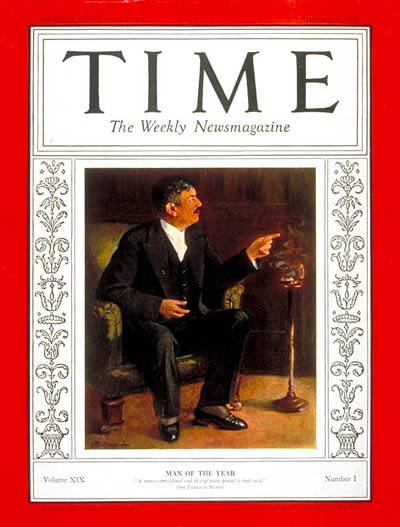

Time’s Man of the Year in 1932

Time’s Man of the Year in 1932

In each case he was convinced that he alone could save France from external enemies (Germany) and internal ones (Communists).

In this biography he seems not to have been a reflective or introspective person. Self-doubts, he had none.

I said ‘delusional’ above. To explain, while prime minister he hoped to befriend Mussolini’s Italy and use it to restrain and buffer Hitler. At the time he started on this policy it had some promise. But to everyone but Laval it soon became apparent (1) that he had no influence with anyone in Italy and (2) that Italy followed and did not lead Germany.

No evidence convinced him to change his course. One rebuff after another from Rome, was dismissed as a bargaining ploy, an effort to conceal his influence from Hitler. In the effort to stop Laval’s endless messages to Rome, the Italian foreign minister wrote a letter, couched in very undiplomatic terms, to tell him to stop and sent it to the French foreign minister of the day who read it in parliament in an effort to silence and embarrass Laval. It did not slow him down a beat.

Later he developed a similar fixation on his capacity to influence Hitler, and repeated rebuffs did not faze him. He had a number of interviews with Hitler, and got virtually nothing from them, but that only led him to try harder to get another meeting where he would surely score a great coup.

One of many meetings

One of many meetings

How others saw him

How others saw him

Nor were his delusions limited to foreign relations. His start as a socialist gave him the abiding belief that he (alone) could unite the social divisions of France. Each failure to do so, he took as a sign that he was succeeding little by little.

One can only admire his tenacity and optimism while deploring his grasp of facts.

Maréchel Pétain was 84 when the Vichy government took form. While the Germans and the French were glad to have such a respected figure associated with the papier-mâché regime, they also considered that he might die at any moment. Anticipation of what might happen if he died, set off one palace intrigue after another as members of the Vichy government manoeuvred to have themselves named as his inheritor. Laval was the most conspicuous schemer but he was certainly not the only one.

By December 1940 Laval had irritated most other members of the six-month old government since its inception in July of that year. He was always a fast worker. In order to secure German good will he had cut across the domains of other ministers and given away French assets for a hand shake, and sometimes not even that. Accordingly, six of the eight other minister convinced Pétain to dismiss him. Pétain did not take much convincing.

It was done with a combination of subtlety and force. It was a ritual of Third Republic governments for ministers to sign a collective letter of resignation which the head of state (Pétain in this case) could use to drop an unpopular minister and placate public option or the parliamentary parties. At a routine 8 pm cabinet meeting one such letter went around the table and each minister signed it. The unspoken assumption, at least in Laval’s mind, was that it would be used to drop a junior minister who was ill and not at the meeting. As per the ritual, when the letter got to Pétain there was a short break and he retired to another room while the others drank coffee and smoked. He came back ten minutes later and said the ‘resignation of M. Laval has been accepted.’ The explosion went off!

Laval, completely taken by surprise, shouted, thumped the table, and nearly cried. To Pétain who had stood down generals under fire this reaction was most unseemly. Laval was bundled out of the room by other ministers and taken into custody by the Praetorian Guard (Pétain’s body guards) and put under house arrest some miles away. Although Pétain had told the Germans a few hours before he was making a change of government, they, too, were surprised and demanded Laval’s immediate re-instatement. Pétain refused. After 72 hours of pistol waving, angry telegrams from Berlin, a new prime minister (who was acceptable to Berlin) was named, and the Germans took Laval to Paris for the next 16 months.

Note that it was in Paris that the real extremists congregated and not in Vichy. The French fascists, the anti-semites, the New Europeanists (code for the German Europe), published newspapers, pamphlets, and books in Paris damning the Vichy government for its sloth, weakness, and lack of enthusiasm for the opportunity to cleanse France. They produced anti-semitic films and curated anti-semitic exhibitions. Applied their creative powers to anti-British propaganda which convinced themselves, if no one else, that Great Britain was the real enemy. They held rallies and attacked all manner of people in the street to show how tough they were. A few (very few) who really believed what they said volunteered for service on the Russian front. Laval was never quite comfortable with these zealots; he was — I think — an opportunist in service of his ambition and not an ideologue.

During this interregnum the Germans kept Laval on tap in Paris as a threat to the Vichy regime. If it did not comply with German requests, the Germans retained the option of creating a new French government in Paris with Laval at the head. Remember that by now Pétain was 86 and he might die at any moment. If he did can anyone doubt, they reasoned in Vichy, that the Germans would crown Laval? For his part Laval toadied, conspired, lobbied, and generally tried to ingratiate himself with German authorities.

Absent Laval, the scheming and musical chairs in the Vichy regime continued. Prime Ministers came and went, each trying to get Pétain to pass the mantle onto him. Ministers and ministries changed monthly or so it seemed. Until November 1942 Vichy did exercise administrative responsibilities of many kinds but once the Allies landed in North Africa that ended. Yet the Germans continued the mirage of Vichy as a means of stability. At the insistence of the Germans Laval returned to Vichy and to government after 16 months of his Paris exile and exacted his revenge on everyone, though Pétain himself and his immediate entourage was untouchable, not so others who were soon deprived of position, income, accommodation, and even papers. The Germans perceived Laval as the most pro-German of the Vichy figures and they also wanted at least the veneer of continuity in the Vichy regime.

Laval, that master of self-delusion, continued to suppose the Germans would win the war and said so often. That had been plausible in August 1940 but it no longer was in August 1944. No evidence could ever dent the Maginot line of his delusions. Throughout 1943 Laval conceded nearly every German demand. Indeed, he only declined in cases where he did not have the capacity to deliver.

Oddly enough as the Vichy regime withered and shrunk in early 1944 there was a clamour from the Parisienne ultras to join the government, and Laval finally agreed, over Pétain’s objections. As the ship was sinking, more rats got on it.

In August 1944 with American, British, and Free French armies a few miles from Paris, the Germans, perhaps out of the same strange loyalty that led to the German rescue of Benito Mussolini, moved Pétain and Laval and few others to a castle on the Danube. Laval had fled to Spain but the Spanish surrendered him to the French provisional government which tried and executed him in short order. Initially Laval seemed to think he was going home to a hero’s welcome.

At this trial he lied as freely, as he had done throughout his career, and when presented the evidence of a lie, he shrugged and went on.

There is no doubt that in the end Laval believed he had done France a great service by buffering the Germans. Like Socrates, he nearly suggested that he be rewarded rather than condemned. The author refutes this claim with some comparisons to other occupied countries like the Netherlands and Belgium who governments went into exile.

His trial was no model of justice, but the author contends that there was and is no doubt that Laval was guilty of treason, however defined, but certainly within the meaning of the relevant French law. A lot more guilty than, say, Alfred Dreyfus or Léon Blum who had been tried on this charge in trials that were not models of justice either. Nor can one deny the conclusion that Laval was also a scapegoat for a lot of other people who trucked with the Nazis.

The book is definitive. It is based on primary sources from French and German archives, both civilian and military, with other material from the United States, which (too) long maintained diplomatic relations with the Vichy regime. It is measured and the prose clear, letting the story speak for itself and letting the reader draw conclusions.

Simone de Beauvoir, who is not mentioned in the book, covered Laval’s trial for a newspaper, and remarked that as much as she hated him, and hate him she did, the Laval that was on trial was not, or did not seem to be, the man she hated. He was diminished, small, uncertain, cowed, not the brash, bull-headed know-it-all man, who crashed through and crushed all in his path. Some of that diminution is physical. Laval’s table had always been sumptuous in Vichy, even when the rest of France starved, but after August 1944 he lived on German army rations and then prison food. He lost weight and colour from his complexion, the hair greyed. His one suit of clothes wore through. Then there is the fact of being on trial for his life…the round shoulders and bowed head. His was no longer the whip-hand. Her essay is reprinted in her ‘Ethics of Ambiguity’ (1962).

Skip to content