A wall poster of General Pétain features in the opening sequence of ‘Casablanca’ (1942) and that film concludes with a bottle of Vichy water tossed into the rubbish bin. That’s about all I knew about Vichy France.

Pétain was 84

Pétain was 84

Whereas every other country Nazi Germany conquered was placed under direct German rule, France was not. The Vichy Regime, as it became known, by the terms of the Armistice was to govern all of France, even though the North was occupied by Germany. The Occupation was only military. Civilian life was the domain of the French government, temporarily located in Vichy.

Divided and dismembered France

Divided and dismembered France

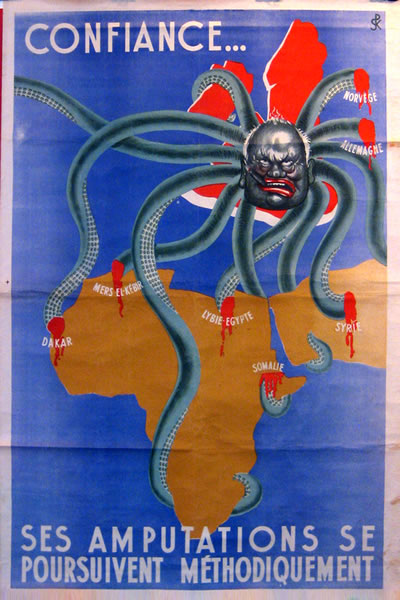

Among the overarching themes in the book are these: First, Vichy evolved as the war developed. It transformed itself, in part, and was later transformed by the Germans. Second, at the start Vichy earnestly sought co-operation with Germany, to which Germany was indifferent for a couple of years, until the tide of the war changed the calculus. Third, Vichy had nominal responsibility for the whole of France, i.e., including the Occupied Zone in the North and West for schools, hospitals, police, roads, and so on. Fourth, in practice France was divided into three not two zones, the third being Paris itself where the German presence was the greatest and collaboration was the most blatant. Fifth, the Vichy regime was internally riven by ideology, religion, region, and personality, united only by an abhorrence of the Third Republic and a willingness to work in Vichy. Sixth, Vichy’s commitment to retaining the Empire ran deep, hence the undeclared naval warfare with Britain, the defence of Syria and Algeria, and Vichy bombing attacks on Gibraltar. Vichy propaganda supposed Britain’s only war aim was to seize the French Empire. In this context Vichy propaganda portrayed General de Gaulle as a puppet for Britain to steal the French Empire away, which partly explains his intransigence in trying to retain every foot of the French Empire from Syria to Morocco.

That is Churchill as the head of the octopus

That is Churchill as the head of the octopus

Germany wanted France out of the war, and did not want a French government-in-exile to continue the war in any way. Why not? After all the Norwegian, Dutch, Polish, Belgian, and Luxembourg governments-in-exile existed and were of little moment.

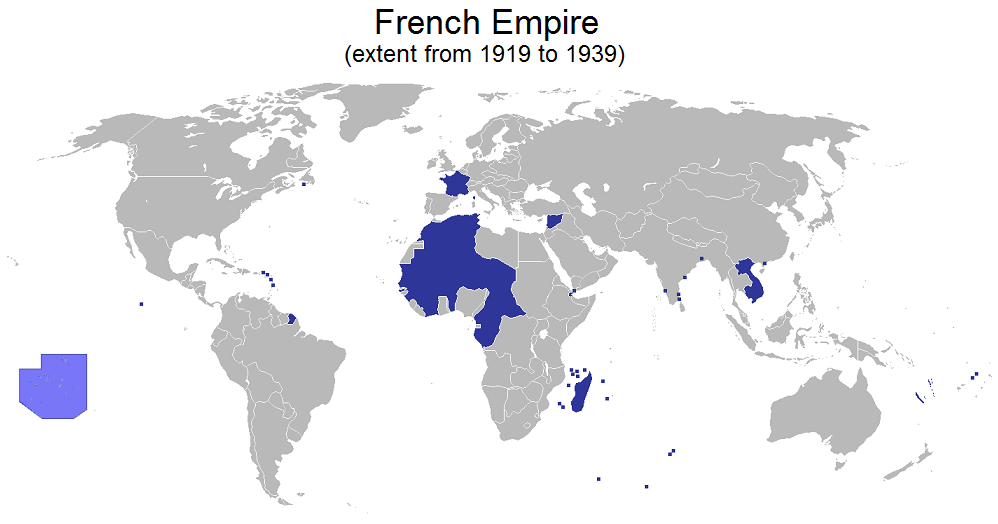

France was different because (1) of its proximity to Britain for the putative invasion, (2) its size compared to these others, (3) its navy which was second only that Britain, and (4) its colonial empire, particularly in North Africa – Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco, and the Levant. A united French government-in-exile might make a very large difference in one or all of these dimensions.

As to (1), in July 1940 the German plan was to concentrate on an invasion Britain as soon as air supremacy over the Channel was achieved, not on occupying and subduing every corner of France. Let the French govern themselves in everyday life, policing, sanitation, railroads, hospitals, water, roads, schools, and so. Call these matters administration. Of course, such administration continued in the other occupied Western European countries but run by Germans. Read on.

(2) The difference in France was size and location. German staff estimates of the troops needed simply to occupy all of France were considerable, let alone what would be necessary to subdue continued resistance in a rear-guard or guerrilla action in the Vosges, Alps, Pyrenees, Massif central mountains or the swamps of the Gironde, Loire, Rhone, and Saone rivers. It was best to make peace so that France could be used as a platform against Britain, and as a resource of food, men, and armaments. As it was the German army of occupation in France numbered a mere 40,000 for a population of 45 million, and most of those Germans were concentrated along the North coast opposite Britain. When resistance attacks began, that number increased and the overall calculus changed.

(3) The French navy was distributed around the world, though much was in French waters, not all. There were major elements in Africa (Algeria and Senegal), and there were 18,000 French sailors and more than one hundred ships in England in June 1940. Germany did not have the means of using the ships in French waters, i.e., it did not have the seaman and officers to man them, still less did it have a surefire way to recall the fleet from Africa, Caribbean, and Pacific. The best option then was to neutralise it by an agreement with the French government, i.e., the Armistice, to keep the ships out of the hands of Britain which might have the means to use them. Hence the fiction that Vichy was sovereign neutral. If and when Germany needed the ships, they would then be available. The fiction of French sovereignty kept the much of the fleet on ice for several years.

(4) Finally the colonies were a distraction to Germany. It had no means to occupy even those of strategic value, e.g, French Somaliland on the Red Sea, Lebanon and Syria (then French protectorates) with ready access to Middle East oil, or Dakar (Senegal) with its excellent deep water port on the Atlantic. Each would have been useful, respectively, to disrupt the Suez Canal, either secure Iraq oil or disrupt British access to it, and to base submarines in the Atlantic. Even so, Germany did not have the means (at the time) to do anything about them. Neutrality would be the best, immediate result to keep them out of British hands while the final battle for Britain occurred and allow for the possibility that later Germany would make use of them, brushing Vichy aside.

However, when Hitler turned east to the Soviet Union, then the demands on France changed, and would change again when the Allies landed in North Africa, expelled Germany from Tunisia, invaded Italy and drove it out of the war, and landed at Normandy. Each time, the German bear-hug on France tightened.

The 1940 Armistice allowed France, alone among the conquered European countries to retain a sovereign government beyond the daily administration alluded to above. France was divided into two zones and Vichy had about 30-40% of the country by either area or population. While much of France’s industry was in Paris and the north, Michelin tires, for example, was located within Vichy and several large manufacturers were in Marseilles and Toulon. The Armistice implied that once the war was won against Britain, the Vichy regime would be located in Paris and the northern Occupied Zone would dissolve. Meanwhile, Vichy received ambassadors from the United States and Canada and thirty (30) other countries, negotiated with Britain in Madrid for French assets, sold war matériel to Italy, imported food from Latin America, appointed new governors to its empire abroad … for a time.

Meanwhile, the regime was temporarily housed in the hotels of the spa town of Vichy. Why Vichy? Because nearby Clermont-Ferrand had the very best railway connections and Vichy itself had the most modern telephone exchange in France, connecting it easily to Paris, Berlin, Marseilles, and any where else. Moreover, one the most influential members of the Vichy Regime had major commercial interests there, and probably lobbied for the location, namely Pierre Laval.

By the Armistice, Vichy had administrative responsibly in the Occupied Zone, and near sovereignty in its Free Zone. Indeed, it maintained an Armistice Army of 100,000, unique in conquered Europe. That it existed, motivated many officers and men to be loyal to Vichy until November 1942 when it was disarmed and disbanded.

Though not stated in the Armistice, Paris quickly became a separate, third zone in everything but name.

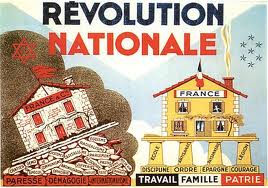

Paxton convinces this reader that the Vichy regime attempted to use the situation to break with the past of France, and start the National Revolution to wind the cultural clock back. The first break with the past was the name. It called itself L’État Français and not La Républic Français. It repudiated the Republic and all it represented. It was a utopian moment when the discredited past burned away, allowing a Phoenix to rise. And because authority was concentrated in the executive, Pétain and the cabinet, with no carping, criticising parliament to be accommodated, it was a green-fields opportunity to (re)create a society afresh by dictate.

The Vichy Regime was Catholic not secular, agrarian not urban, insular not cosmopolitan. It did not celebrate the Rights of Man but rather the duties of a good Catholic to pray, work the land, procreate, and shun outsiders. On grounds that a religion brings order and calm it embraced Catholicism, though none of the principals of Vichy was ever religious, and certainly not Pétain himself, still less Laval. The school curriculum was changed and the Catholic Church invited to re-enter the classrooms from which it had been expelled after the Revolution. Science was de-emphasized. Curriculum committees set to work cutting French literature down to Vichy-size, big ideas out, duty and humility in. Girls were encouraged to pray and bear children for France. Withal, the author argues that Vichy was not fascist, but rather nationalist, nostalgic, and conservative. For example, its anti-Semitism was culture not racial. Hence the efforts of Vichy, ineffective though they were, to protect converted Jews.

Paxton shows in a great many ways that the Vichy Regime strove to be an active partner with Germany when it seemed that Germany’s final victory was only a matter weeks away. Again and again, Vichy took the initiative to expel Spanish Republican refugees, to identify foreign Jews, to surrender arms, to bomb Gibraltar, to turn over information, to oppose Britain in word and deed, and to excoriate de Gaulle. Later, by 1944 the tables had turned and Vichy was merely a German catspaw, but that was not the case in 1940, in 1941, in 1942, in most of 1943, and even in some ways in early 1944.

Phillipe Pétain headed the Vichy government, bringing to it little more than his name, as the victor at Verdun in 1917 and a reputation, in contrast to so many in World War I, for saving the lives of his men behind fortifications and not spending them in pointless attacks. He was 84 years old when he took over. German intelligence kept an eye on all things Vichy including Pétain himself, and its assessments repeatedly confirmed that the old man had his wits about him, though he tired easily in the afternoons. We should all be so fit at that age.

When the time came the Vichy regime made itself a German catspaw. To make work in the South it negotiated contracts for war matériel for Germany. When Germany demanded slave labour, Vichy conscripted it. When Germans retaliated for resistance attacks by shooting hostages, Vichy volunteered to do that, and in some cases exceeded the German appetite for blood, as both local and national authorities settled old scores, personal and political. Most of all it delivered up Jews ever easier. Once on the slippery slope, the only way was down and down into the levels of Hell.

Frenchmen arresting Frenchmen to please Germans.

Frenchmen arresting Frenchmen to please Germans.

French volunteers against Bolshevism on the Russian Front.

French volunteers against Bolshevism on the Russian Front.

Paxton chronicles the infighting, careerism, exploitation, profiteering, undermining, conflicting personalities within the hothouse of Vichy, though he offers no explanation for the remarkable dismissal of Pierre Laval in 1941, who bounced back and exacted revenge on his real and imagined enemies. The seamy side of Vichy is well realised in some of J. Robert Janes’s krimies set in this time and place like ‘Flykiller’ (2002).

One of the claims of Vichy was stability. Unlike the volatile Third Republic where governments lasted six months at best, and often less, Vichy would be a rock, as Pétain was at Verdun. Vichy propaganda repeated that claim untinged by the fact that its was a government set to musical chairs with six ministers of defence in one year, and a parade of prime ministers (until the Germans put a stop to it): Pétain, Weygand, Laval, Flandin, Darlan, and Laval again in less than 2 1/2 years. The Third Republic had longer periods of ministerial stability than Vichy ever had. Rather reminded me of the Murdoch media where what matters is repetition not veracity. Pétain wanted to remain prime minister and tried to regain that post but lost in these manoeuvres Laval.

Pétain and Laval. They despised one another but were bound together in a bargain with the Devil in Berlin.

Pétain and Laval. They despised one another but were bound together in a bargain with the Devil in Berlin.

This book also makes very clear just how very alone Charles de Gaulle was on the 18th of June 1940 in London and how alone he remained for quite a time, making his creation France Libre all the more remarkable. De Gaulle remained alone because the chain of command in the army and the colonies held, despite the catastrophes of the defeat, the surrender, the occupation, the dismemberment.

There are honorable exceptions to the unalloyed vanity, venality, and immorality of Vichy. General Charles-Léon Huntziger, whom Charles de Gaulle specifically invited to command Free France forces, chose to stay at his post to share the fate of his soldiers in captivity, signed the Armistice in that railway car, and then worked tirelessly on the Armistice Commission to secure the release of French prisoners of war by any and every means, and met with some success.

To end where we started with ‘Casablanca,’ the Governor-General of French Morocco, Hippolyte Noguès, held to Vichy despite his own expressed conviction that the Reynaud government should retreat to Algeria and continue the fight from there. This was soldier who obeyed orders, however distasteful. But when by the terms of the Armistice a German commission arrived to monitor the French troops there, he restricted the movements of its members, assigned them a police escort, insisted they wear civilian clothes, put them in poor accommodation, and tried everything within his limited powers to minimize their impact. ‘Casablanca’s’ Major Strasser would not have been allowed to wear his uniform, click his heels, drive around with a Wehrmacht guard, or start a bar fight. Not quite as accommodating as Louie Renault in the film. On the other hand, in 1942 when he was told, the day before, that American forces would land, he was ordered to resist, and he did for three days before surrendering. Not quite the romp show in ‘Patton’ (1970).

The book is informative, insightful, meticulous in the use of evidence, precise in drawing conclusions, and makes extensive us of German archives. It is also somewhat repetitive, which suggests more organisation is necessary, and there are annoying lapses in composition. Too many sentences end with ‘however,’ ‘moreover,’ and ‘of course.’ Far too many. There are also cryptic references to French history better suited to the seminar room. The author compiles some compelling data, especially in the final chapters, that is, quantitative, calories a day, total costs, tonnage of shipments, and the like, and these are presented as lists in paragraphs. While the presentation of evidence is welcome, this method detracts and distracts. Better to have presented as much of this evidence as possible in charts, graphs, and tables to give the reader a picture to put the detail into perspective.

Postage stamp catalogues feature stamps printed but not distributed by the Vichy regime for France’s far flung colonial empire. By early 1943 Vichy had lost contact with most of that empire, apart from North Africa (Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco), and by 1944 all of that empire had gone over to Free France, with the exception of Indochina which the Japanese had occupied much earlier, despite the protests of Vichy. Germany made no effort to discourage this Japanese strategic move. Yet the stamps kept coming off the presses.

In a time of desperate shortages, when skilled manpower was at a premium, when printing presses were being broken up to be re-fashioned into weapons, when oil was a rarity, at this time the Vichy government had printed by the thousands in Paris those postage stamps for all of its lost empire. Almost none of those stamps were ever issued, that is, they not transported to Madagascar, Réunion, Nouvelle Caledonie, St Pierre et Miquelon, Guyana, or the Antarctic station. An example suffices. New stamps for St Pierre et Miquelon were issued six months after those strategic islands off the Atlantic coast of Canada had been occupied by an Anglo-Free France force. Reality did not intrude into the process, once engaged. Anyone who has worked for a larger organisation knows the truth of that fact.

Issued in 1943

Issued in 1943

Is this a case of bureaucracy gone mad? With the new constitution of Vichy the colonies had to have new stamps, so new stamps were produced regardless of the circumstances. Possibly. Another explanation presents itself, though, continuing to make work like this shields the workers from conscription for slave labor in Germany. The stamp designers, the stockmen, the inkers, the suppliers of ink, paper, and glue, the auditors all become essential workers in the Vichy administration. With this make-work perhaps some Frenchmen were protected from the dreaded Service de Travail Obligatoire.

Skip to content