Andrei Sakharov designed and built hydrogen bombs for the Soviet Union in the 1950s and 1960s. He also dissented from the regime during much of that time until he became a full-time dissident in the latter 1960s. I have wondered how he compared to Robert Oppenheimer and this is a start in finding out. Strangely enough Sakharov loomed larger on my horizon than Oppenheimer because Sakharov was a celebrity dissident in the 1960s, repeatedly in ‘Time’ magazine and in the highbrow publications of the Centre for Democratic Institution from which I drank at the time, whereas Oppenheimer was a man of the past.

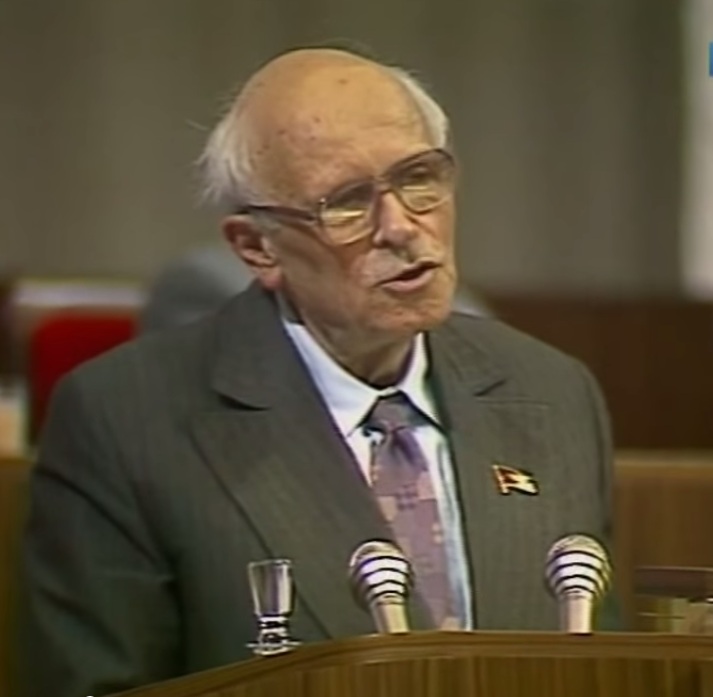

Andrei Sakharov, 1989

Andrei Sakharov, 1989

Sakharov was man and boy Soviet, knowing no other way of life like the millions of others. His family was secure and comfortable by the standards of the time and place, though Stalin’s purges and the myriad of local purges that cascaded onward in time caught up with members of his family, first among the older generation of uncles, and then aunts whose crime was to have married that uncle, and then Sakharov’s generation, an arrest here, a deportation there. Even so his loyalty to the regime was unalloyed.

He grew up in a musical family, while his father was a successful physics teacher who wrote and published numerous approved high school texts on the subject. Sakharov’s interest in and aptitude for mathematics blossomed and he went to the head of the class and stayed there. Having just seen ‘The Imitation Game’ (reviewed elsewhere on this blog) I compared him to Alan Turing.

He failed the physical examination for the Soviet army in World War II; consider for a moment how low that standard must have been. He had an irregular heart beat most of his life. Instead he signed up to work in an ordinance factory. There his capacity to reduce confused and confusing reality to rows of numbers led him to several innovations which made his name as a coming man.

One example suffices. To test artillery shells for defects the method was manual, in every new batch several shells were dusted and examined with a magnifying glass for cracks in the casing. Until that test was passed the batch waited. If one crack was found the whole batch was rejected. Neither effective nor efficient. Sakharov devised a laser to pass over each shell individually and ping on cracks so that individual shells could be rejected but not whole batches and the production line kept moving the whole time. I have take quite a few liberties in this description to make it accessible; as they say in movie credits, ‘based on a true story.’ In the same spirit that could be motto for Fox News rather than that ironic statement ‘Fair and Factual.’ It is ironic isn’t it?

There is one of similarity to Turing. Both turned to automation for tasks that previously had been done by hand, just as the machine gun replaced the bolt action rifle.

Sakharov’s change from cog in the mighty wheel to dissident came slowly. He saw neighbours and colleagues foully treated and it could not all be explained by the war. Jews were made victim. A loose word about comrade number one, and … Exactly, no one quite knew.

Moreover, when he left the laboratory for the factory and later the weapons plants, which were really cities in themselves, he saw how badly treated workers and their families were, despite the endless rhetoric of the workers paradise. Also he choked on the ritualistic evocation of Marxism-Leninism at every official juncture. Just as many of us have choked on the empty and ritualistic evocation of God on public occasions like the Gallipoli ceremony.

He was a brilliant scientist, a claim reiterated many times in these pages without a satisfactory explanation of this brilliance or how it was recognised as brilliance by all the dimwits around him. Well, they have to be dimwits if they did not reject the regime per Bergman.

Gradually, Sakharov tried to use the status he had to help individuals and in time he realised that the Stalinist regime was the problem, and that it rolled on even after its creator died. He retained a faith in the Soviet promise but thought it perverted by Stalin. At first his supposition was that the Tsar did not know, in the old Russian proverb, only slowly concluding that the Tsar was the problem, then Tsarism including the people who wanted a Tsar, call them the Tsarists.

Though his interventions were few, carefully judged to appeal to Soviet values, and argued on pragmatic grounds they yielded a vigorous reaction. He was named as errant in public by Chairman Khrushchev himself.

In time he realised there were systematic and systemic failings and those he saw first and most clearly and which he quantified were the deaths and defects causes by the radiation of atmospheric testing of hydrogen weapons. He compiled spreadsheets of data that showed approximately 10,000 deaths caused over three generations by the radiation released in a single atmospheric test. He thus argued for underground testings, which had technical limitations, in his immediate environment, then at closed and secret scientific conferences, and then by writing to the Party Chairman.

Yikes, this drumbeat was readily characterised as unpatriotic, just as Edward Teller tried to portray all other others who lacked his one-eyed enthusiasm for ever bigger bombs as UnAmerican.

His ground shifted from urging reforms on pragmatic grounds to improve Soviet society to urging reforms because they were morally right. This put him beyond the pale; it put him in Groky four hundred miles east of Moscow.

There is a personal element as well. Sakharov saw and despaired at medical treatment his first wife Klava received. Doctors at elite clinics could not interpret X-Rays to his mind. She died in a great pain as he watched. Perhaps it could happen anywhere but it happened to him and it was another fissure in his allegiance to the Soviet Union.

One of the things that tied Sakharov to the Soviet regime withal his objections was the need for weapons not because of the Cold War with the West but because of Mao’s China and its erratic course as perceived from Moscow. That was a new perspective to me.

One of the things that loosened the tie to the Soviet regime was the Prague Spring of 1968. We read that many Soviet dissidents saw in those Czechoslovakian changes a hopeful future for the Soviet Union itself. When that door slammed shut in August 1968, those Soviet dissidents who championed reform from within communism lost hope. It was proof that communism could not change. This was another new perspective to me and a striking one due to our recent visit to Prague and our tours of its communist relics.

The many and varied dissidents could not agree among themselves and spent at least as much time and effort in undermining each other as working for reform of the Soviet way. (Sounds familiar to any seasoned committeeman.) They tried to organise themselves in the way they knew, a central committee with a rigid hierarchy….and that did not work. All of this backbiting made it easy for the regime to isolate and pick off dissidents.

He became a supporter of any and all dissident causes from ethnic revanchism to free masonry, seemingly without discrimination. His enemy’s enemy became his friend. Anyone who dissented from the Soviet way was his friend, or so it must have seemed to the Communist authorities. He also demonstrated a political naiveté born of his sheltered existence in believing that some how all these dissenters could combine within the abstraction of human rights, when some of them did not want human rights, they wanted their land and would gladly kill to get it! See post-Soviet history for the data.

He seems to have had a charmed life in that even when stripped of his scientific duties, he was still paid, retained his apartment, had a limousine and driver at his service, was available to all manner of foreign journalists in Moscow to whom he spoke ever more freely, including offering advice to the Reagan administration on how to negotiate with the Soviet leadership – rather like Jane Fonda encouraging the North Vietnamese to kill more American draftees to shorten the war. (Oh, yes she did.) For a man who was oppressed and repressed he published a very great deal in the way of political opinion, a bibliography of which runs from page 413 to page 431.

Mikhail Gorbachev appeared but for Sakharov he was too little, too late. Sakharov wanted everything now, and Gorbachev was carrying a heavy load on thin ice. That Gorbachev let him return to Moscow and appointed him to ceremonial offices was accepted but it did not temper Sakharov who but now seems unable to trust anyone or give anyone else credit for good intentions. Then Sakharov died and Gorbachev offered his widowed second wife, Yelena Bonner, a state funeral which she accepted. That became a Saint Bartholomew’s circus for dissidents, for apparatchiks who wanted a halo, for Western journalists looking for easy copy.

I should have said earlier that Bonner, of Jewish descendent, did much to focus Sakharov’s political interests. She had a much more general and coherent view of the Soviet Union in contrast to Sakharov’s piecemeal perspective. She became a comrade in arms, as she appeared to be at the time in their hunger strikes.

Yelena Bonner

Yelena Bonner

Returning to the comparison with Oppenheimer, this book being my only source, it is not clear to me if Sakharov had management responsibility akin to Oppenheimer’s. None are explicitly mentioned though Sakharov is occasionally referred to as ‘Director’ of this project or that and the word implies management to some degree.

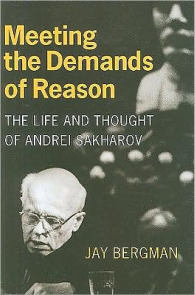

The book was a hard slog. The implied thesis behind the title seems to come straight from Karl Popper that science and democracy unite in falsifiability. Neither assures perfection but each can falsify mistakes through rational argument and evidence. Ergo, the more rational and scientific Sakharov was, the more he had to reject (falsify) the Soviet system and make his way (intellectually) to democracy. Oh dear, does that mean the Soviet scientists who did not move this way must not have been rational and scientific after all, and likewise that the Western scientists who pined for authoritarian government, hello Ed Teller, were not either. Such consistencies do not worry the author.

Our author has it that one of Sakharov’s deepest concerns with the Soviet Union was the easy and irrational way in which scientific arguments and evidence put before the top leadership were cast aside. Stalin and Khrushchev having grown up among farmers rejected scientific biology on the strength of that background. Bergman implies this rejection of scientific, reason, is one of the core evils of the Soviet Union. Arrrrrrrgh! What would Bergman make of political leaders today in the West who reject climate science in one sentence or less? Evil?

Similarly, Bergman in contrasting Sakharov with that other even more famous dissident of the time Alexander Solzhenitsyn takes Sakharov’s side because Solzhenitsyn was too much a believer in the mystical soul of Russia for the scientific age of reason and democracy. Hmmmm. What would Bergman make of those Tea Party nut cases invoking God above to reject vaccines and fluoride because Moses did not have any. Evil?

In the same vein, Bergman speculates that Sakharov wanted the rule of law as he supposed it existed in the West. Well maybe but convince me. Quote that phrase ‘rule of law’ from something Sakharov said or wrote. [Silence.] The ‘rule of law,’ let’s ask David Hicks about that shall we? Montesquieu evolved a theory of government that inspired the writers of the Constitution of the United States to divide and separate powers; Montesquieu reasoned from the British example where he thought it existed but in fact it did not. Nonetheless, the illusion bred reality. (With difficulty I will refrain from mentioning that smirking Queensland journalist who made a name nationally by misunderstanding the separation of powers doctrine. Such are media reputations.)

Jay Bergman

Jay Bergman

Even though published twenty (20) years after the fall of the Berlin Wall this book is a Cold War salvo. Every few pages another evil of the Soviet regime is described, denounced, and then placed in relation to Sakharov with some long bows.

There is virtually no science in the book after the early pages, and the science there is in inaccessible to this reader. The last chapter on Sakharov’s legacy which addresses exclusively his dissidence. Period.

I still do not know what made him a brilliant scientist.

Skip to content