Bletchley Park first was unknown, then a curiosity, a historical drama, and now a fantasyland.

Bletchley Park, now open to the public.

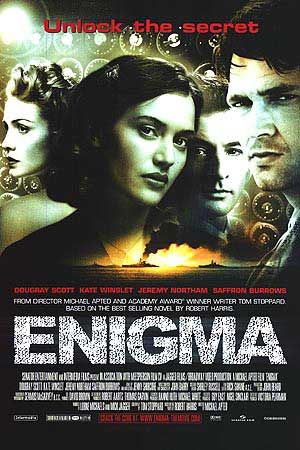

It remained secret for most of the Cold War, then a little information became available in the 1960s, then a lot more in the 1980s, and now the facts no longer constrain the story teller. ‘Enigma’ in 2001 was one take on it, a drama with a tortured performance from Dougray Scott and Kate Winslet playing against type. It was perplexing and rousing.

In 1968 Dirk Bogarde ran the show in ‘Sebastian’ with understated panache.

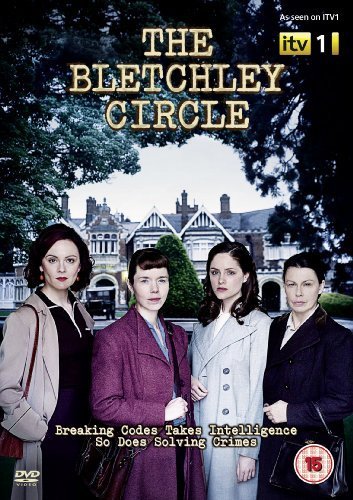

’The Bletchley Circle’ has also been on the small screen, which after a great start descended to the average, emphasising special effects over intellectual content.

We dithered about going to ‘The Imitation Game.’ Seeing man’s inhumanity to man, well, we could see that on the television news any day. Huh? The publicity emphasised the abuse of Turing for his homosexuality; no doubt this was done to martyr him, but it put us off. For a while.

Bletchley Park, I had to see that again. Nerds winning the war! Near sighted, stoop shouldered, shuffling wallflowers with bad table manners, I could identify with them! Sorry Brad Pitt but you are not in my league.

The importance of codes and decoding has a long history to be sure. There is that Zimmerman telegram of 1917, a coded German message to Mexico that was intercepted and decoded and gave the United States a push into the war. More on the Zimmerman letter at the end. Read on.

To compare ‘Enigma’ to ‘The Imitation Game’, a few points standout. ‘Enigma’ showed Bletchley Park to be the gigantic factory it was, employing in 1944 about 12,000 people. The Bletchley Park’ of ‘The Imitation Game’ is confined to less than a dozen people with a few CGI backgrounds. In ‘The Imitation Game’ Commander Alastair Denniston is a foolish martinet, played to a ‘T’ by Charles Dance, but in fact he was the one who decided very early that code breaking in this war required mathematicians and engineers. In earlier years, decoding had been the province of linguists and translators. Not this time. Likewise, running crossword puzzle competitions to recruit personnel was his, not Turing’s, brainchild. Nor do I think the beard is right for 1942. None of the pictures I could find show him with a beard in the 1940s.

Colossus was indeed a digital computer but it was neither designed nor used by Turing but by others. Turing devised and built another device, but the film is ‘based on a true story’ so the slather is open.

Many reviewers have focused on Turing’s homosexuality, and it certainly was the man. For the one-eyed there is not enough emphasis on that, no doubt, but to this viewer it seemed partly anachronistic, i.e., the references were too explicit for the time when homosexuality was the love that did not (dare) speak its name. The very word itself in 1942 would have not always been understood. Having said that, there was plenty of emphasis on it, though Turing suffered also from autism, and code-breaker he might be, but he could not see double meanings in conversation, a fact that is very nicely presented in the scene in the pub. There was also paranoia in the mix.

There is no historical reason to believe that Turing made any decisions about the use of the material. Disclosure by using the intelligence, this was a command decision made at the very top. though Turing may have realised the implications of acting on the information but it hardly seems consistent with his complete self-absorption most of the time. Making a member of the inner circle, who apparently does nothing, a relative of a sailor on a convoy was a very midday soap opera touch. Every ship had brothers and sons on it, a good many wives, sisters, and daughters, too. ‘Enigma’ plays this straight and the result is all the more powerful when the senior naval officer implicitly orders his men to their deaths for the greater cause.

It seems very unlikely to me that a one page letter from Turing to Churchill would have uncorked a £100,000. Perhaps Leo Szilard, Churchill’s science advisor, interceded, but we will never know in ‘The Imitation Game’ where Turing is the singular Atlas on whose shoulders the world rests. On the same page the confrontation after the door is kicked in seems almost childish in its resolution where the messenger from the Home Office without word of dialogue has the authority to nod to a six month extension but mutely accepts a one month edict instead. Hello! It does not work anything like that.

Turing did write to Churchill at one point to ask for more clerical staff, and Churchill did reply immediately for ‘Action this day.’ Based on a true story they say. Hmm.

I found the chopping back and forth through time from 1928 to 1942 to 1955 confusing and distracting. The only reason the schooldays of 1928 were there in the end was to explain the name Christopher on the last contraption Turing built. It was unnecessary to the story.

Benedict Cumberbatch strives to save the day and nearly does. He does not need that backstory of 1928 to be confused, arrogant, inept, autistic, brilliant, frightened, determined, lost, secretive, brassy, paranoid, unpredictable, lonely in a crowd, and more. He did them all by turns and at times a couple at once, riveting.

Alan Turing

The female lead by comparison goes through the motions without ever quite inhabiting the part, made more difficult for being underwritten. She becomes nothing more than a plot device. Joan Clarke in fact became Deputy Head of Hut 8 which housed the first Colossus, but you’d never know it in ‘The Imitation Game.’ And she did not secure this position by patronage from Turing, to be clear. By the way she wore glasses, as did Kate Winslet in ‘Enigma.’ Hooray for Four Eyes!

The idea that the air is full of secrets is quite an idea and I wished the film makers had scrapped the CGI warfare, which was uniformly poorly done, for something creative. Would there not be a way to show those messages passing through the air like tracers and being netted at British listening stations. Now that would excite any viewer. Maybe something like this map of transponders on European air traffic.

There are several scenes of Turing running and he was a Olympic class distance runner, who failed in an Olympic try out because of an injury. One of his many personal eccentricities was to run to London for meetings, carrying a back pack with clothes. Another was to chain his perfectly ordinary tea mug to the radiator.

The imitation game is still a test for artificial intelligence pretty much as described in the police interview room where Turing breaks the Official Secrets Act he signed in 1939 to tell the plod all.

The Zimmerman telegram was decoded and acted upon in 1917 by a team that included Alastair Denniston. A feeble effort was made to hide its source, and the Germans continued to use the same code. More intelligence from broken codes was used, and the German continued to use it. Even when the pretence of hiding the sources was dropped, they continued to use it. Why? Because it was a German code and so it was the best. It was unbreakable, despite the evidence that by the middle of 1918 the Allies were reading every radio message. See Barbara Tuchman’s marvellous book ‘The Zimmerman Telegram’ (1985) for tale of his Teutonic arrogance and folly matched only by that of the United States.

Skip to content