Where were you when France fell? That was certainly a memorable day for those born in the 1920s.

Impregnable France, eternal France, the France of Napoleon, the France of Clémanceau, the France of the taxi cab offensive, the France of Verdun, the France of Jean d’Arc, indomitable France, this France dissolved in the powerful acid of the Wehrmacht.

‘Thank God for the French Army,’ said Winston Churchill in 1935, for it was the bulwark that stayed the German beast. Yet less than five years later it proved to be a wall in a Japanese house, made of paper.

In 1940 where was the France of Union Sacrée of 1914-1918 when all social strata, all social classes, all degrees of political opinion, all regions put aside their historic animosities and united without question against Les Boches? It was gone.

In the Twenties French politics descended into blood sport. With the ancient external enemy vanquished and emasculated, French political differences sharpened once again, each with a backlog of grievances to be settled. Without an external threat to encourage a degree of forbearance, cooperation, and restraint the gloves were off.

Any of this starting to sound familiar?

One’s opponents were no longer well meaning, but misguided, people. They were detestable enemies whose very name was sin. They were alien spawn to be eradicated right now, if not sooner. With such people compromise is impossible!

Internal enemies completely replaced external enemies and they were everywhere: in schools teaching pernicious doctrines from science to scholasticism, in trade unions practising black masses, in plutocrats dining upon working class babies….. No vituperation was enough! No exaggeration too far. No lie too big. From 1934 many observers thought civil war in France was imminent. When such a war began in Spain, they supposed the example would light the many powder kegs in France. Against that backdrop, the drama played itself out.

Yes, Mortimer, it is all starting to sound like the Tea Party and Fox News.

In the 1936 election some of the very many political parties actively campaigned under the slogan ‘Better Hitler than Blum.’ Léon Blum was the leader of Socialist party and he was feared more than Hitler. Ludicrous, to be sure, for Blum was a moderate to his finger tips and a true patriot and if any thing he was a brake on the hotheads in his own party. Blum, by the way, was a Jew, and the explicit attacks on him in parliament for his Judaism authorised a hate campaign in the press the like of which not seen before or since. His every gesture and word was sign of his nefarious plots. Compared to Blum, Dreyfus was small potatoes.

To the most right-wing parties, blocs, movements, and groups the real threat was Britain, seen to be constantly scheming to grab the French Empire. Albion was the enemy, not Hitler. And Albion’s agent was that Jew Blum and his ilk.

Blum did form a Popular Front government in 1936, striving to keep France out of another war. Though by then the die was all but cast. He depended on the votes of the Communists and the Radicals (centrists, despite the name). Neither was reliable, each had its own agenda.

In the last decade of the Third Republic political musical chairs is the only fitting description. The electorate was fractured into innumerable political parties which combined into coalition governments, briefly, to divide the spoils of office, and then lose a vote of confidence. An incoming minister grabbed everything thing that was not nailed down, cancelled all commitments of the previous minister, signed a raft of new commitments, and six months later was thrown out of office when that coalition failed. Democracy at work.

During one five year period there were eleven (11) ministers of defence. Each dedicated upon entering office to demolishing everything the predecessor had done.

Contracts to build tanks, were torn up. Though the government paid a penalty to the contractor, the tanks were not built. To secure as much popular support as possible, contracts for tanks, aircraft, artillery were spread widely. Instead of concentration on one fighter plane, France built a dozen different types around the country, with no economy of scale. But it bought votes.

One minister boasted that in France it took 18,000 man hours of work to build a warplane and a mere 5,000 man hours in Germany, proving the superiority of the French approach that generated more demand for labour! That Germany thus produced three planes to every one in France was beside the point.

In 1936 when German workers put in 60 hours week in defence industries, those in France were awarded a 40 hour week with much jubilation. That ratio of 3:1 does not capture it all. German industries were more efficient because they were centralised. Germany did not dabble with a dozen different kinds of warplanes but concentrated on only a few to reach economies of scale far beyond anything the French could do. Finally, the brutal facts of demography apply. Germany had nearly twice the population of France, the more so when it digested Austria, the Sudetenland, and Czechoslovakia.

It gets worse. The French Communist Party had worked hard to organise workers in defence industries on orders from Moscow. From the mid-1930s obedient to Stalin’s orders some of these workers sabotaged French war industries. Some of this sabotage occurred during the war in 1939! The Soviet policy was to make it easy for the Germans to go West.

In all of this the French army was complicit, though of course after the Defeat, the generals spent the rest of their lives lying about it. Ambitious generals had learned to play the parade of governments off against each other to win promotion and ever more gold leaf on the kepí. One general after another advanced his career by telling the ministers of the day what they wanted to hear. Dissent within the ranks was silenced, e.g., Charles de Gaulle was struck from the promotions list, posted abroad, and forbidden to publish his criticisms of military strategy along with several others.

Here is one singular example. Pétain blamed the Defeat on the politicians who had cut the defence budget. Hmmm. Class! Who was minister of defence when the defence budget suffered its greatest cut? Go on, guess! Phillipe Pétain! The generals blamed politicians, Free Masons, protestants, free thinkers, women wearing slacks, school teachers, physical education instructors, Jews, Albion, the Belgians, the Dutch, newspapers, journalists, novelists, travel writers….. Any one but themselves. Now back to the Third Republic.

When vitriol replaced argument in public life, the night creatures dared to reveal themselves: anti-Semitism became a public pastime. The Dreyfus Clock was turned back. The Communist Party of France openly acknowledged its obedience to Moscow. The plutocrats stole pension funds on a national scale. Political interference meant even those few police officers who were not corrupt could not investigate major crimes against persons or property. It does all seem like the End of Days.

All of this is a familiar story, what Horne adds to the picture was Gallic arrogance. As France was the fountainhead of European (read ‘World’) civilisation, others would rush to its side if ever the worst happened. This, Horne suggests, was one of the central, unspoken, shared assumption of every French government after 1919. It followed that no matter what the French did or did not do, the firemen would come. Though the firemen are lesser beings, they are useful, and they will come from England, America, Canada, Romania, Poland, Czechoslovakia…. to save us even if we set ourselves alight.

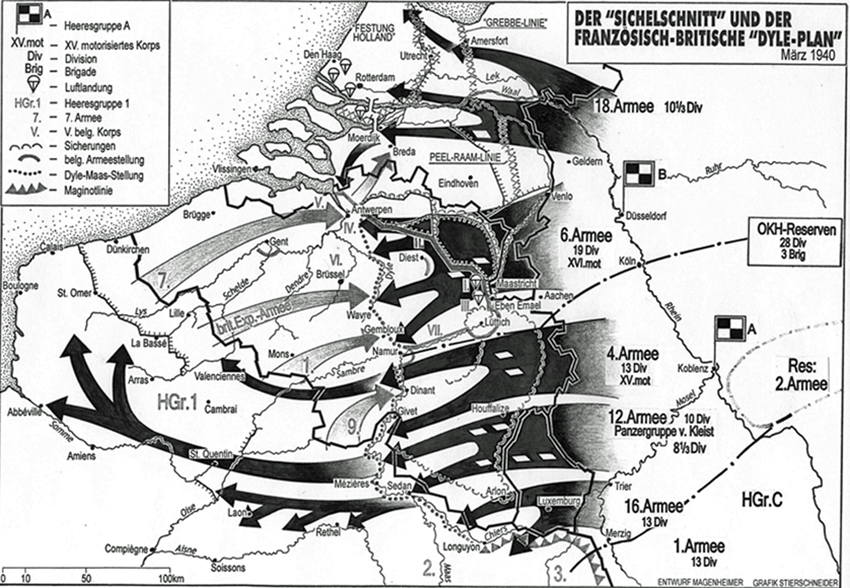

It seemed to this reader — though Horne does not say it — that part of the French response to the German offensive in May 1940 was that its generals, from Maurice Gamelin to Maxime Weygand, thought, moved, and acted on trench time. They were in no rush because after all trench warfare goes nowhere. If Gamelin took three days to think things over, there was no rush. Yet the German armoured Panzer divisions were moving 40 – 60 miles a day! By the time Gamelin made up his mind to authorise the French 2nd army to disengage and pivot, the Germans were no longer within striking distance. Indeed the 2nd army had already been forced to retire because the Germans had outflanked it. Gamelin used neither radio nor telephone but motorcycle couriers to communicate with his five armies.

Gamelin reacted to this pressure of time by delegating everything downward. He would make no decisions. Let others decided, and then be responsible for the consequences. But of course no one else could give orders to all the armies and generals involved but Gamelin. Very quickly each French army was left in isolation to cope as best it could alone. There was no coordination. Here’s an example. The British Expeditionary Force of General Gort was under the command of a French Army in Belgium. As the Germans were crossing the Meuse River, Gort had no orders, information, or contact from his French commander. None for eight (8) days. Is it any wonder he decided to stay close to sea.

Horne makes it clear that Hitler prevented the Germans from refighting the last war. He was the only head of state who had been in the trenches in World War I, though Churchill and de Gaulle had been, they were not heads of state until later. Moreover, Hitler was an autocrat who had powers no democratic politicians in England or France ever had. Got the picture?

Hitler loved machines and he reviled the trench warfare he had experienced. When he rebuilt the Wehrmacht he wanted tanks and airplanes. When an obscure German Colonel Guderian advocated tanks, Hitler promoted him to give his advocacy a wider audience.

Heinz Guderian

Heinz Guderian

When French Colonel de Gaulle advocated tanks, he was struck from the promotions list and exiled to Syria. Germany built tanks, armoured cars, self-propelled cannons and concentrated them in regiments, divisions, corps, and armies. Mobility and manoeuvre were the watchwords.

The French were stuck in 1916. Their major strategy was continuous defence of the whole border from Switzerland to the North Sea. Not one foot would be yielded for one instant to the invader. The manpower needed to defend these hundreds of miles was gigantic. In addition, the commitment to static defence led the French General Staff, which reluctantly accepted those new fangled weapons of tanks and airplanes, to distribute them all along the line. Every division had a few. They were never concentrated, and once the shooting started, it was not possible to concentrate them, to deliver a resounding blow. Instead the tanks and airplanes went into battle in small groups. A German Panzer division of 200 tanks would encounter 200 French tanks in a week, but each time in groups of 5. No contest, even though individually the French tanks were technically superior. When 200 Panzers hit 5 Renault tanks, it was over in a muzzle flash or two.

In fact, the French manpower required for continuous defence was so great that there scarcely more than two divisions in reserve. This fact dumbfounded Churchill when he was told that. Note: very often the troops held in reserve outnumber those in the line, so that when the enemy attacks or retreats a large, fresh force can be unleashed.

The manpower shortage was produced by the strategy, but it was compounded by the politics of the Third Republic. To buy votes successive ministers had reduced military service and inserted exemptions of all manner. The exemptions were so numerous that when Paul Reynaud, a minister who feared the Germans and was serious about defence, cut 30 pages of exemptions from the conscription law, another 20 pages remained. Wine was deemed of national importance and anyone who worked in the wine business was exempt, etc. Renaud angered many people and was dumped from the job.

To his credit Reynaud kept trying and was prime minister during the fateful six weeks that led to the capitulation. His coalition cabinet was full of rivals and pretenders and he had little authority among them. Yet he persevered and in the final hour, he very nearly alone wanted to fight on. It is clear from Horne’s pages that the generals — Gamelin, Weygand, Pétain — gave up long before he did.

They yielded in part because they, and many others of the haute bourgeoisie feared a repeat of the Paris Commune in 1940. All French military police (Garde Mobile) had been concentrated in Paris to keep order, code for preventing a left wing revolution or right wing coup d’état.

At the eleventh hour they did prefer Hitler to Blum.

Horne lays to rest one of the myths of the War concerning Hitler’s order that halted the Germans short of Dunkirk. The German armour was miles in advance of infantry and artillery, many miles. Moreover that steel tip was by then at half strength, with battle loses, mechanical breakdowns, and the exhaustion of the men. Fuel trucks were finding it hard to get through the debris. A halt had been considered several times before. In addition, the German intelligence estimated only 40-50,000 Allied soldiers in the Dunkirk enclave, and the conclusion was that the Luftwaffe would suffice to disrupt any evacuation on that scale. It was also supposed that RAF’s losses had been so great it could not cover any evacuation. Finally, because Gort, having withdrawn to Dunkirk, in good time had fortified his position against tanks. Ergo, Hitler decided to draw a breath. The halt was not a conciliatory gesture to the British nor was it a blunder. It made sense in the context.

Horne also emphasises that the Germans, surprised at the speed of their successes, had no plan for a next phase, namely an invasion of Britain. Nothing. Nada. Zip. So why be in a hurry?

The German were successful in part because the French assumed the strategic target was again Paris as it had been in 1870 and 1914, and never realised that the strategic objective was the North Sea, having first lured massive allied armies into Belgium and the Pas de Calais, and then cut them off, encircle them, destroy them, and only then move on to Paris.

The vacillation of Belgium before the war played in the hands of the Germans. Belgium shifted back and forth between a French and British alliance and then neutrality. The Belgians did not want the Maginot Line extended to their frontier with France and lobbied hard against it. Yet, fearing arousing the Germans, they did not want an explicit alliance with France or Britain. Uncertainty all around.

Alistair Horne

Alistair Horne

As to the book itself, Horne’s command of the subject is complete. Highly recommended. However there are typographical errors in this the third edition which were there in the the first when I read years ago. Horne’s style is orotund. It takes him a long time to get to the point and the passive voice confused me more than once. More than half the book is devoted to the details of armies, movements, skirmishes, battles of little interest to me but in between there are shafts of insight into the people and events that repay the reader.