When he retired William Lyon Mackenzie King held the record for the longest serving prime minister in the English-speaking world, exceeding the record then held by Robert Walpole, in all 21 years. To put that in perspective, note that Australia’s Robert Menzies had 18 years and Franklin Roosevelt 13, and Churchill 11. In addition, King was the leader of the Liberal Party for a total of 28 years. I expect he still does hold the record for longest serving party leader, too.

William Lyon Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King

Roosevelt had a charm even over the radio and daring ideas, Churchill could wake the dead with his rhetoric and was willing to try almost anything, while Menzies exuded confidence and calm. King had none of these assets. He was short, round, and pudgy. He had no love for meet-and-greets. He spoke in a high squeaky voice that sounded worse on radio than in person though it sounded bad then. He invariably read his speeches word-for-word badly. He had no electoral coattails to make backbenchers beholden to him.

Then why did he succeed? The short answer was said in an obituary ‘He divided us least.’

The legends of King are many, and most have to do with inaction: he never let his left hand know what his left hand was doing, he never did by halves what could be done by quarters and he never did at all what did not have to be done. Like a duck holding place against a tide, he paddled furiously below the surface while doing nothing up top. That image is from Churchill in another context but it fits King perfectly.

It is said that he had all cabinet ministers sign undated letters of resignation as a condition of being named to cabinet and that he kept those in his pocket in parliament during debates or question time occasionally bringing one or all out onto the desk as though about to date a resignation and by this means stimulating his colleagues to fervour. This book does not mention this last story and rather emphasises the care he generally took in stroking the egos of those around him in his earlier years, but it is also clear that he changed over the years, and grew ever more determined to hang on. Still he had plenty of wiles, like calling an election in the speech from the throne! Students of parliamentary procedure will realise how startling that would be.

In his youth, before the concept existed, he became an experienced and successful labor-management mediator in some pretty difficult circumstances. His approach was to get the parties talking, sometimes about trivial things, like where to meet, the shape of the table, and the like, to get them into direct dialogue about something, anything concrete. All the while he would present the factual context and try to get them to agree to the description of the situation. In this effort he was deferential, polite, patient, and had an iron butt to see the job out no matter what.

He was headhunted into politics when a PhD student in economics at Harvard. He entered parliament and became Canada’s first minister of labor in one swoop. His mentor was Wilfred Laurier of the $5 bill made famous in tribute to Mr Spock in 2015.

In office he championed social welfare measures but never tried to push ahead, always waiting for the community to accept such measures as child bonuses, pensions, and so on. His touch in these judgements was sure though there is no telling how or why he had it, since he seldom left Ottawa and when he did, he avoided voters as much as possible. In the few campaign rallies where he spoke he entered by a backdoor, read his leaden speech, and left. With experience he became a more accomplished speaker but never in the same league as his contemporaries, Churchill and Roosevelt. Canadians could hear both the latter often, and King did not try to compete with them.

His reluctance to push ahead irritated many who urged prompt action to use the votes he had in parliament, but King never hurried. Never. The votes in parliament were necessary but what was sufficient was the mood of the country, and divided Canada has many moods, all at once. For example, to some child bonuses were paying Catholic Québécois to procreate.

Divisions! Plenty of those. The prairie provinces are alienated from Ottawa. Not to be outdone the left coast of British Columbia is even more alienated. The impoverished Atlantic provinces are home to the forgotten people. Prince Edward Island cannot be found on some maps of Canada. Quebec is a world unto itself outside Montréal. Labrador and the Northwest Territory are on the dark side of the moon. Ontario owns most of the country. Federal elections were won and lost in the Ottawa River valley, i.e., Ontario and Quebec.

King became leader when he was the rising man, and also at a time when the Liberals seemed certain to lose and none of the other likely candidates wanted the job. He got it, and he kept it.

Many winners are born lucky in their opponents, and King certainly was. The Conservatives found one way after another to alienate vast sections of the electorate, usually by preferring Ontario’s interest to the exclusion of the rest of the country, and making no effort in Quebec which was ceded to the Liberals. In effect, the Liberals were the only national party (sound familiar?) in Canada for much of this period, getting votes and seats in every part of the country. There were elections in the only Conservative seats were from Ontario with a very light sprinkling from nearby Manitoba.

Having observed Laurier, King determined to keep Quebec Liberal at all costs. He did this by finding a loyal lieutenant, first Ernest Lapoint and then Laurier St. Laurent (who later succeeded him as leader and prime minister), to concentrate on Quebec. King pretty much gave them a free hand. He seldom went there, spoke no French, and viewed Catholicism with suspicion.

Over the years there many remarkable events, among the most outstanding were these.

First, the Bynge Affair. As the incumbent prime minister he was at loggerheads with the Governor-General after an election produced no majority. The Liberals lost a substantial number of seats and the Conservatives won many new seats but neither had a majority. The convention would have been that King resign and step back and let the Conservatives form a government, but he hung on for weeks and argued the point with Governor-General Bynge ad nauseum. He finally did resign and the Conservatives tried and failed and a new election followed where King secured a thin majority. Why he protracted the matter is hard to fathom and the author can only say that he was a selfish man, hardly a satisfactory explanation, since King was smart enough to know what he was doing, but what was he doing? King had predicted that the Conservatives would fail, indeed he told that to the Governor-General as a reason why he should stay in office, but he would not back his judgement until pinned to the wall.

Second, King advocated a Canadian foreign and defence policy so did not agree to accept all British decisions or recommendations. Unlike Australia’s Robert Menzies, he did not participate in the Empire War Cabinet in World War II. Instead he said Canadian decisions will be made in Canada by Canadians in the interest of Canada, spending very little time in London, again unlike Menzies. This line outraged the Canadian Britophils, especially in British Columbia which has long lived up to the first part of its name, but it soothed Québécois. It did not satisfy anyone but it did not completely alienate anyone either.

Third, though he advocated unemployment relief in principle, when the Great Depression hit he was unprepared for the magnitude, and he did not warm to John Maynard Keynes’s approach to government budget deficits. Moreover, he was rude and crude publicly in his reaction to protests. No man of the people was he. Moreover, he refused to let the federal government cooperate with the provincial governments held by Conservatives, a sorry example of vindictiveness replacing compassion. Not one dollar to those provinces which hath sinned against Mackenzie King! He lost the next election and found opposition dead boring, leaving the running to others. In a way this loss was lucky for King and for the Liberals because it left the Conservatives in office in the teeth of the Great Depression, and so left them to carry the opprobrium for not combatting it.

Four, there is no doubt his crucible was World War II and conscription. In World War I Canada had poured men into the Western Front, and had taken a perverse pride in the lists of dead. The drain on manpower was incredible, and Laurier slowly and reluctantly accepted conscription. While English Canada was ready for it, Quebec was not.

A brief aside, Québécois speak French but have no love for France. Like the Boers of South Africa who speak a Dutch, they feel they were abandoned by their country of origin, traded away at a conference table. At times Québécois think of themselves as Normans abandoned by Parisiennes.

Laurier legislated conscription in 1917 before the USA entered the war and it led to riots in Montrėal and produced few Québécois soldiers but much ill will. King wanted no repeat of that. His line, which pleased neither the zealots for Britain, nor the Québécois was no conscription unless necessary and conscription only if necessary. It had no ring to it. But if it did not please either camp, neither did it fatally alienate either camp.

In 1944 the Canadian army wanted men to replace its battle losses, including 2,000 at Dieppe which is barely mentioned in this book. But after the middle of 1944 the outcome of the war was inevitable and King would not budge, despite the pressures brought to bear from generals, Liberal backbenchers and ministers, the press, the opposition, and the British and American allies, he held firm. One argument for more troops was that a greater commitment would give Canada a larger role in the peace that followed, say at the United Nations. King had no interest in such aggrandisement. The price was too high. Conscription in July 1944 when the war was all but won in Europe, and Canada had little interest in the Pacific War, would have produced a rupture with Quebec, and would have jeopardised the Liberal lock on it.

While he held off those who wanted more troops he was calm up top, furiously paddling down below.

Five, in the post-war period when a Soviet defector revealed a spy ring in Ottawa, King smothered it, at least compared to the way similar revelations in the United States and Australia were fanned into flames. Those implicated were pursued but he did not try to exploit it with the electorate though that was urged on him by many associates. As always he preferred the minimum, not the Aristotelian mean, the absolute minimum.

In his personal habits he was notoriously frugal and recorded, in the best Scots tradition, every penny he spent. This personal frugality carried over into a reluctance to spend government money. Even for cherished projects like unemployment relief in the Depression.

He never married though many women were courted in his early life, none quite made the grade. There is no mistaking his loneliness in his mature and later years, though our author is insensitive to it. That he was a bachelor was an oddity, for then as now, the norm is that the democratic leader to be a normal, married man, façade though it may be. The exceptions are few and none with King’s endurance.

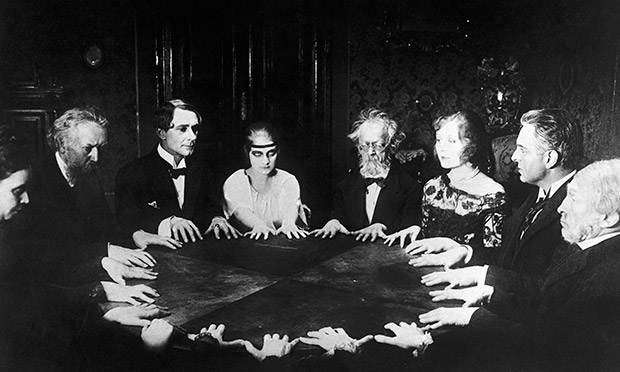

Stranger still was King’s life long obsession with spiritualism. The author has many derogatory things to say on this subject and only grudgingly notes that spiritualism had a following among many educated and intelligent people at the turn of the twentieth century. King attended sėances, consulted fortune tellers, had tea leaves read, and so on, all this meticulously recorded in a diary he kept all of his life, writing 5, 10, 15 pages a night in long hand which he had typed and filed each morning, leaving behind a houseful of boxes and binders of this diary.

Yes, Prime Minister!

Yes, Prime Minister!

He never seems to have read a book or listened to the radio for amusement or relaxation. His only relief from duty, apart from his love of dogs, was this diary. His only companion was a dog, three Irish setters, one after another.

Even more unusual is his near childlike belief in an enchanted world where a cloud formation foretold events, or a draft that blew a paper to the floor was a sign. Everything that happens, and I mean everything, from leaf drops, to birds in the sky, they were all communications of meaning which he recorded in his diary, linking the cloud shape to his decision to appoint X to this or that post. He confided these enchantments to his diary and did not tell X he got the job because of a cloud looked like him!

King combined this spiritualism with a Christian duty to serve mankind. The book is silent on his church-going habits and how he squared what he heard in church with his spiritualism. By the way the focal, but not exclusive, point of his spiritualism was his mother, giving the pop psychologists much fun. Our author has no feel for religion in one’s life and treats it as a hobby, one that is less amusing than the spiritualism.

As he aged King became a tired old man who took out his aches and pains, and loneliness, on his staff. He worked many to the bone, and some to death, and seldom thanked any of them. There is megalomania in all that. It is always about King. When a subordinate dies at his post doing his bidding, King’s first reaction is irritation that the chap let him down.

His name needs explanation: William Lyon Mackenzie King was the maternal grandson of William Lyon Mackenzie, himself a formidable figure in Canadian history and politics. It was his mother’s father’s example that led him into public life, and it was an inspiration he acknowledged now and again over the years in stressing his sense of duty. The author has hard time playing this with a straight bat. There are enough cheap shots in this book to please Bill Bryson.

The book has had many accolades. This reader will not join the chorus. I found the writing sloppy, the organisation repetitive, the analysis of King’s political successes and accomplishments just greater than 0. Instead there much sneering at the spiritualism, again and again, meanwhile accepting events as inevitable rather than examining the dynamic that brought them about. While the author notes King’s enormous capacity for delusion, he accepts most of the factual assertions in King’s voluminous diaries, seldom seeking confirmation from another source. Contrast this approach to Robert Caro’s Herculean double-checking in his biography of Lyndon Johnson. Most of King’s delusions stemmed from the enchanted world he inhabited, which often made him seem to be central figure. If Churchill wrote him a letter about some routine matter that was conclusive proof that Churchill admired, respected, and was influenced by him.

Allan Levine

Allan Levine

Explanatory note. Above I have referred to Québécois and not French Canadians. Many French Canadians live outside Quebec and they seldom identify with it and its causes.

Skip to content