A biography of KOM, as he was sometimes called. A Canadian, a Kansan, a Quebecker, a New Yorker, depending on which lie he was telling at the time. O’Malley (1854-1953) spent 65 years in Australia in Hobart, Launceston, Melbourne, Perth, Sydney, and Adelaide. Often one step ahead of bailiffs. Indeed taking ship to Australia in the first place may well have been to evade creditors when he was about 25 years old.

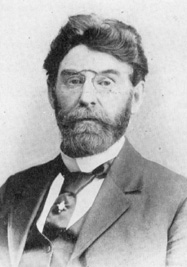

The man himself, King O’Malley

The man himself, King O’Malley

To establish himself with audiences here and there he claimed a variety of backgrounds and motivations, uninhibited by what he had said previously elsewhere to other audiences, and there was no social media to trip him up. So convincing a liar was he that he convinced himself, repeatedly. And audiences he had to have. He was a man who craved attention, and found it to in sound of his own voice. He looked and sounded American to his contemporaries in Australia, but he claimed Canadian birth to qualify for citizenship and a run at parliament, first in South Australia, and then in Canberra.

He started out selling insurance but discovered, as have others like Huey Long, that the product he could best sell was himself.

Loud, brazen, boastful, egotistical, obnoxious, he was just like all Americans in the Australian stereotype today. So thought many then but more fool them because voters elected him. His political career started in South Australia, borne, said his foes, on the votes of women who found him a handsome and dynamic man. So much for Enlightenment Adelaide. Having sold insurance most of his life made him — in his own mind — a financial expert, that plus the United States had a national bank were enough to convince him of the need for national bank in Australia. It was a theme he played throughout his political career and in the end he was one of the driving forces in creating the both the Commonwealth Bank and also the Reserve Bank of Australia. There were many objections to both.

Physics is so simple, as Isaac Newton said, for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. In politics for every action there is a myriad of diverse reactions that roll on and feed on themselves. Together they far exceed the original action, and they go off in so many directions that they cannot be tracked.

While he advocated many causes on the nascent Labour agenda at the end of the 19th Century, he was reluctant to join that party and accept the discipline that went with it. Round the turn of the 20th Century the party system did not have a deadlock on seats, and there were a number of independents. Nonetheless, he supposed he would get a cabinet seat. Someone had to tell him to join that club he had to join the party club and he became a Labor man. His constituency was Darwin in Northwest Tasmania though he lived in Melbourne in the main.

He was minister for home affairs in two governments where he seems to have made a point of clashing with the officials in the Department. Accordingly there was a great deal of smoke and lightning, but the snail’s pace continued.

Because he was a rootless bounder, he had traveled far and wide in Australia selling insurance for years before entering politics. Consequently he had seen more of the country most of his colleagues and that led him to advocate a national railroad. Another theme he stayed with for years.

Perhaps his most lasting mark on Australian was to support Walter and Marion Griffin’s design for Canberra, and to stand by that design and the Griffins when the political football game began. There were many ups and downs but they remained friends so that in his 60s and out of politics when O’Malley paid his only return visit to the United States he stayed several weeks with Walter’s parents in Elmhurst near Chicago.

O’Malley at the ceremony inaugurating the site of Canberra

O’Malley at the ceremony inaugurating the site of Canberra

As O’Malley aged he matured. Many of the passages quoted from Hansard on the bank, the railroad, or Canberra as far less bombastic and more reasoned than his comments on the same subjects twenty years earlier.

By the way, he was a teetotaller all his life, though he freely bought drinks for others, clients and voters. Yet there is pub in Civic in downtown Canberra that bears his name on the stereotype that all Irish are sots. When travelling he never stayed at a licensed hotel such was his aversion to drink and drinkers.

The pub in Civic

The pub in Civic

He was personally frugal to a fault with his own money and that of the Commonwealth. Religion is not mentioned. King was his mother’s maiden name. He spent about twenty-five years in retirement burnishing his reputation. He married Amy in his 40s and they stayed married, though our author speculates that King was not a romantic. Having bought property whenever he could along the way, he was a wealthy man and he arranged for his estate to support scholarships for girls only. In the 1960s a Canberra suburban was named after him.

This short book is judicious and droll. It should be of interest to anyone who has wondered about Canberra came to be as it is. It faithfully recounts O’Malley’s words and deeds and then slowly applies a great deal of salt to arrive at conclusions. It is far more circumspect than the credulous entry in Wikipedia. Likewise the entry in the ‘Australian National Dictionary’ of biography is very cautious.

Skip to content