René failed because he succeeded. Ever a paradox.

Many people loved René and many people hated him, and still more both loved and hated him. He is the one person whom I would say was charismatic. He burned with a message akin to those religious prophets that Max Weber coined the word to describe. I saw him once in person in a very small audience in Edmonton, and many times later on television. There are plenty of clips on You Tube. But, well, you had to be there to feel the electricity in the air. At the 1980 defeat the rapturous crowd response and his simple and direct statement: ‘I understand’ perhaps suggest his quality. Remember this is the leader addressing the troops in defeat. It is on You Tube.

The book does not try to be a biography inquiring into the growth and shaping of the man, but is rather a summary of his life and career. It filled in many gaps for this casual observer.

Readers who do not know René can start with the three facts.

1. He was always called René by everyone from bus drivers. journalists, enemies, admirers, voters, opponents, to body guards. Like the eponymous television characters Lovejoy or Morse, René had only one name.

2. When he resigned from office after nearly a decade and cleared out his one bedroom apartment where a plastic milk crate served as a coffee table, he took away his worldly belongings in a plastic supermarket bag. He had long ago given his apartment in Montréal to his divorced wife. (He lived his short years in retirement on his parliamentary pension.)

3. The epitaph from one close and sympathetic English-Canadian observer was: his words stopped more than one riot.

He was from Gaspé, a distant and isolated region where the living is hard, but his family had connections. He was a lousy student and dropped out of Laval University in 1944 for military service. But unlike the Québécois hero of Hugh MacLennan’s ‘The Two Solitudes’ he did join the Canadian army.

René did everything his way: He went south and enlisted as a translator and liaison officer in the United States army serving in Europe with Patton’s Third Army. He saw Dachau within days of it liberation, and that vision stayed with him for the rest of his days. In 1950 he went to Korea as a correspondent, this time with Canadian troops.

Like many, veterans and not, he later embellished these experiences in many ways, but somehow managed to live those fictions down. He did tell lies, to make it plain.

The author suggests three legacies his 1944 experiences that forever shaped the man:

1. Democracy. He arrived in London in 1944 to a society under siege, yet he saw Hyde Park orators excoriating Britain for its coloniziation of India. Here was a country on its knees, everything rationed so thin as not to exist, with nearly every man and woman in a crude uniform – some with wooden rifles, V-rockets falling every day killing thousands, and yet during all-clears polite Indian orators excoriated England to attentive and polite crowds. If that was democracy, it was what he wanted.

2.Les maudits Français. He never had any interest in or respect for France. Later when he met French presidents and foreign ministers, he seldom did more than go through the motions. De Gaulle’s (in)famous remark from the balcony of town hall in Montréal, sent René into a rage. Another Frenchman interfering in something he does not understand. More colonialism!

3. Dachau was the outcome of blind nationalism. Never will he do, say, or acknowledge anything that goes down that road.

He become first a radio broadcaster and then a television presenter who explained the world to Québécois(e) in the 1950s. The backward nature of Québec in the period is hard to believe. Maybe one fact says it all. In 1875, yes in 1875, the provincial government of Québec abolished its Department of Education. It vacated education, leaving it to the Catholic Church. Few children went beyond 6th grade. Most girls left sooner. The curriculum was approved in Rome.

On television his genius for keeping it simple paid off. He soon had his own program ‘Point de mire’ (Focus). The author makes it clear what a refreshing breadth of air he was on a medium largely dominated by the sanctimonious and inscrutable at the time. His viewers were working class Québécois(e) and he spoke directly to them. Other presenters spoke Parisienne French, many were from The Church, some even spoke Latin on Radio Canada, most talked either down to the audience or over its head. All were dead boring. (For the literal minded, note that Radio Canada broadcasts both radio and television.)

Then came La Revolution Tranquil and he was recruited as a Liberal candidate and within weeks was a cabinet minister. He had zero (0) relevant experience. He had never managed a staff or a budget, and had never delivered anything concrete. Yet he was a whirlwind.

In a few weeks he convinced a cabinet, where there were many long-serving foot soldiers who resented this celebrity candidate, to nationalize electricity!

René, ‘My way or else!’

René, ‘My way or else!’

Hydro-Quebec was born, and it employed French-speaking engineers, accountants, technicians, specialists, receptionists, linesmen, repair crews, damn builders, managers, and secretaries. These skills in turn had to be learned and taught, and the Department of Education was rejuvenated.

The Québec flag atop a building with the Hydro-Québec logo

The Québec flag atop a building with the Hydro-Québec logo

Along the way he upset many apple carts, like putting every contract to public tender. Incoming Liberals had rather been counting on rewarding supporters with contracts on the sly, and here was a minister who made it all public. Reluctantly, others had to follow…the leader. He also closed his door to contractors who wanted to woo him. Non! It all goes through channels and all the channels are public. Again other ministers found they had to do likewise.

The old saying is that every Québécois is an independentist at least an hour a day. René’s experiences as a minister led him quickly to conclude that Québec could only become a modern society if it ran its own house. The financiers in Toronto called the shots to benefit themselves. The Church wanted acquiescent worshippers. The politicians in Ottawa were always looking to an abstraction called Canada. For both, leaving Québécois to hew trees for paper and draw water for hydo-electricity was enough. Backward, barefoot, and pregnant would be fine. The colourful natives can stay that way.

In a few years he started a movement to secure a special relationship for Québec within Canada that morphed into the Parti Québécois, and a few years later he was the PQ premier of Quebec. It was a roller coaster ride.

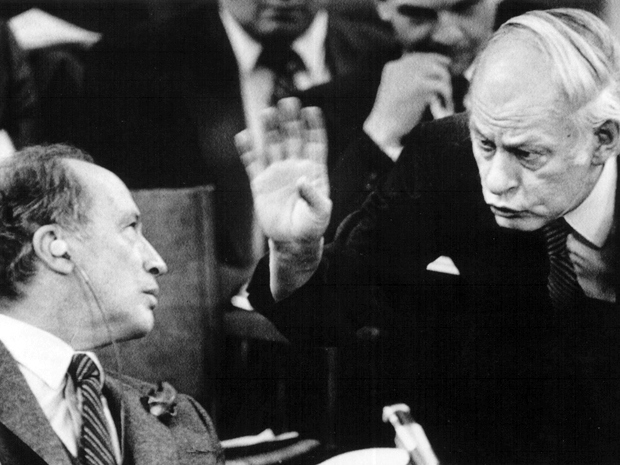

He prevented riots. When Pierre Trudeau faced down the rioters himself in 1968, René was also hosing down the hot heads, and he had a lot more credibility with them than Trudeau. These two, Trudeau and René, were well acquainted and they lined up on different sides, Trudeau for Canada first and last, and René for Québec first and last. For a decade or more their axis dominated Canadian politics. Each had wins; each had loses.

Pierre Trudeau and René Lévesque

Pierre Trudeau and René Lévesque

The rough rides included the FLQ crisis and the War Measures Act that put armed troops on the streets of Montréal. As much as René reviled the War Measures, he was the first and the loudest to condemn the FLQ and stopped more riots. Years later when a convicted FLQ member (having served his time and out of jail) entered a PQ rally, René slammed down the microphone and stormed out. He would NOT be in the same room with that murdering scum. (Though that individual was not himself a murder, he had conspired with them.)

This latter was a card he played often to keep in line the Saint Bartholomew’s circus that comprised the PQ. Do it my way or get a new leader!

A few more bumps in the rough ride include these: two failed referenda on sovereignty, manslaughter, a soldier shooting up the Assemblé Nationale in Québec Cité, and a double agent. Who said Canadian politics is dull?

René the democrat accepted the referenda results, and saw to it that even the zealots in the PQ accepted the results, too. That took a lot of doing, and another threat to quit. Another riot averted.

A Canadian soldier killed three people in the Assemblé Nationale in an effort, he said, to destroy the PQ government. René was not in the building at the time but he hosed down the reaction. No riot this time either.

The manslaughter occurred when René drove home after a long, acrimonious meeting in a bitter January winter snowfall, having drunk — no doubt too much — French wine he ran over and killed a homeless man. The victim was well known to the police for harassing motorists and lying on the road to make them stop so he could ask the drivers for money. René ran over and killed him in the snowfall and called the Sûreté du Québec. Given his many enemies, including aspiring rivals in the PQ, that he was exonerated is convincing. (Note: my driving experience in Montréal left me with a strong impression of hostile and aggressive pedestrians. Nowhere else did I met people who, passing by, yanked open the car door to ask for money, a ride, or pass an opinion on out-of-province license plates.) This event is recounted in Michel Basilieres’s Québec Northern Gothic novel ‘Black Bird’ (2004), which I enjoyed enormously.

The double agent? It turned out that one of René’s closest cabinet colleagues had been recruited years earlier by the Gendarmerie Royal du Canada (RCMP) to inform on radical student groups and he continued to take the payment thereafter. When confronted with the facts, as only René could do, face-à-face, the minister argued he had penetrated the RCMP for the cause! An explanation that René did not dignify with a reply. Well, he did reply: NON!

Perhaps René’s finest hour came the day after he resigned as premier. There was the ceremonial dinner. It was all conducted in French among 600 guests from the political, administrative, media, lobbying classes. At the end René spoke English to invite the one person, having sat through several hours, who spoke no French to join him on the podium and to speak to the assembled group in his language. This man who had come a long way at his own expense spoke Inuit and thanked René for his years of effort at improving the lives of the First People above the Arctic Circle. Indeed, René had done so much that other provincial premiers and finally the Federal Government had had to match his efforts in education, health, welfare, and more.

But the medium was also the message. We can speak our language; so can he.

That should whet any appetite. There is more in the book.

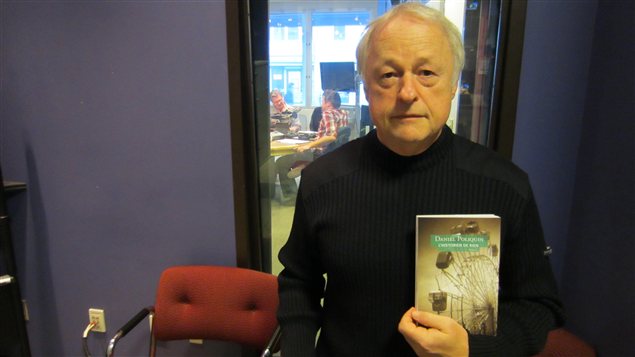

The author pulls no punches and it is a better book for it. René told lies at times. He was prone to self-dramatisation, as if his life did not have enough drama. He was bad father and a terrible husband, and treated the many women in his life as disposable. The confrontational ‘F off, I am indispensable, and you’re not’ was used too often later in life when the patience of this impatient man was exhausted.

He drank to excess, and was sometimes legless and when so, he was rude and crude.

He was nearly a midget with a bulbous head ever more revealed by thining hair, an outsized nose with a drinker’s veins in between ears the size of hockey gloves. He had one suit of clothes and when it decayed he bought another of the rack. His clothes were always smeared with cigarette ash for he was a chain smoker; the 2-3 packs a day were what killed him.

Charisma indeed! Whatever it is, he had it. Yet he was not handsome or good looking in any sense. He was not saintly in any way. He did not sound like an oracle. He seldom smiled. Told no jokes. Was no glad-hander or baby kisser.

He was completely indifferent to money. When the police took him in after the manslaughter he had $5 in his pocket. When died he left a bank balance of $2,800. He assigned the royalties of his memoirs to an Inuit trust in his will.

Daniel Poliquon

Daniel Poliquon

The author’s summation is brilliant. René failed because he succeeded. To explain, he failed in the referenda because he had already succeeded in imbuing Québec and Québécois with the self-confidence to become master of chez nous without sovereignty.

Skip to content