This novel is derived from the the life of Job Harriman (1861-1925) an American socialist leader. He was Eugene V. Debs’s running mate in the 1900 presidential election. He also contested the mayoralty elections in Los Angeles twice prior to the Great War.

1911 campaign button

1911 campaign button

Though afflicted by tuberculous he campaigned with a fierce determination. Giving up on politics later, he led a band of true believers into the Mojave Desert east of Los Angeles to carve out a city on the hill at Llano. That effort failed and a splitter group followed this Messiah to the wilderness of Louisiana to New Llano in the pine forests on the Texas border.

The Los Angeles elections were brutal, marked by street fighting and bombs. Harriman was born to the priesthood, and campaigning gave him a chance to preach which he did with vigour and vehemence. Those who were trying to establish labor unions saw socialist politics as a distraction or worse. Then there were the Wobblies who had no use for union incrementalism or socialist election campaigns. All three of these elements were well represented in Los Angeles before World War I. Ranged against them were the plutocrats and robber merchants of the era along with the railroad magnets, who were the worst of a bad lot. In between these zealots, as always were the decent majority.

In the novel Harriman (in these pages styled Bannerman, for some reason) campaigns diligently for the Debs ticket in 1900. ‘Based on a true story,’ as they say in Hollywood, because Harriman did not campaign at all. Harriman could barely abide being in the same room with Debs (who was a union man first and last) and Harriman went to a conference in Europe to talk about socialism during the entire campaign. Because of his origins and commitment to labor unions, the hope was that Debs would unite the factions but he was reviled by the holier-than-thou socialists like Harriman and despised by the Wobbles. Harriman was on the ticket not to help Debs campaign but to hold a place for a real socialist.

The ‘dynamite’ in the title has two meanings. The first is Harriman at the pulpit; he was a dynamite speaker. The second, literal meaning, refers to the bombing of the Los Angeles Times building in 1910. The owners blamed the socialists, labor unions, and Wobblies without bothering with the minute distinctions among them that so pre-occupied them. The socialists and labor unionists said that the owners had blown it up to put the blame on them. The Wobblies wished they had bombed it. If all this starts to sound like the Reichstag fire in 1933, there are parallels. No doubt some among the plutocrats would have been capable of such a deed, but they did not have to do it.

Clarence Darrow led the defence for the two brothers accused of the bombing, and Harriman worked with him. But the bombers confessed, having killed twenty-one (21) workers and injuring a hundred more, it hardly seemed a blow for the cause. The novel slides over the top of these facts, as it does many others. Bannerman-Harriman convinces himself, perhaps thanks to a feverish dream caused by his tuberculous, that the bombing and subsequent trial represented some kind of victory for socialism.

The move to Llano proved difficult in every respect.

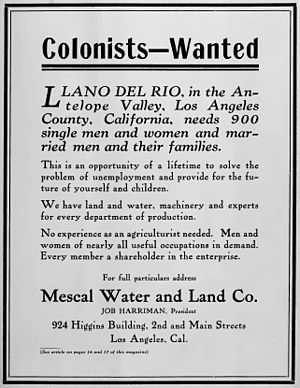

Recruiting advertisement

Recruiting advertisement

The one thing that money cannot buy in Southern California is…water. The Mojave desert, home to Joshua trees, is called a ‘desert’ for a very good reason.

Joshua Tree

Joshua Tree

Llano was on the edge of the Mojave and water was scarce. The United States Weather Service says the average daily temperature at Llano ranges from 37C to 41C over a year. Whew! Booming Los Angeles soaked up all the water there was. See ‘Chinatown’ (1974) for a reminder. Long after Harriman and his band of believers left the area, Aldous Huxley spent some time nearby using peyote and, he said, starting to write ‘Brave New World’ in that drug-induced state.

Ruins at Llano.

Ruins at Llano.

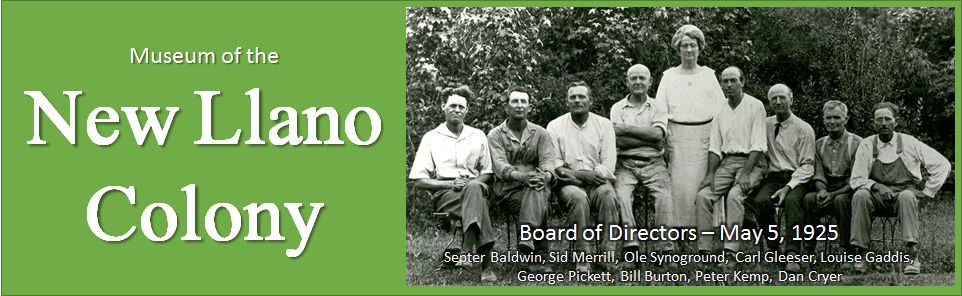

A hard core followed the prophet Harriman to the pine forests of northwest Louisiana near Leesville and founded New Llano which eked out an existence for a few more years in a sawmill operation. It demonstrated admirable pragmatism in finding means to sustain itself, unlike many other intentional communities. The economic boom of World War I made the mill profitable, while those in New Llano denounced the war as a plutocrats’ war and avoided the draft with ingenuity. In both Llano and New Llano Harriman was something of a tyrant imposing his will on one and all, when he had the strength to do so, but that is omitted from this story. One of the reason Llano fractured was because, as one participant said, they had but exchanged one boss for another. By the way, Job Harriman was no relation to Averell Harriman (1891-1986) of New York.

From Museum of West Louisiana

From Museum of West Louisiana

The Los Angeles Times had sworn a vendetta against Harriman, it seems, and it maintained the rage with repeated press attacks on him while he was in Llano, and even when he moved to Louisiana it did not relent. The attacks were as creative and truthful as Fox News. The Llano colony lasted three years and New Llano another seven years. In the annals of such intentional communities ten years is a good run.

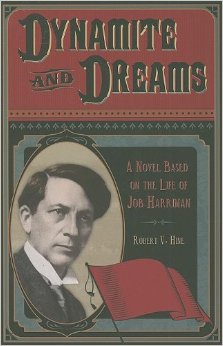

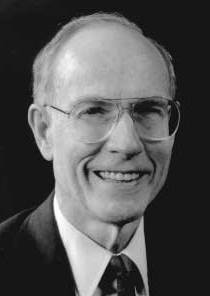

Robert Hine

Robert Hine

California historian Robert Hine turned his hand to novels, this being the second. It is all rather didactic and the characters are all surface.

Skip to content