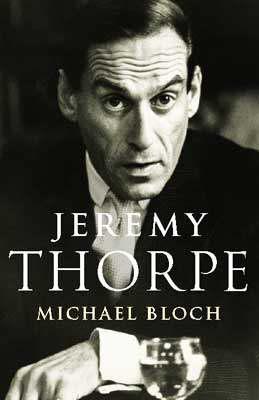

This is a lengthy and detailed biography of one Jeremy Thorpe (1929-2014). Jeremy who? He served in the British parliament for twenty years (1959-1979) and was leader of the Liberal Party, 1967-1976, until a spectacular fall from grace. Educated at Eton and Oxford, he was a scion of the upper middle class of his time and place, reared by nannies, sheltered and seldom disciplined. His mother doted on him as the only boy in the family to the occasional resentment of his two older sisters. Jeremy was fifteen when his father died, and thereafter the money slowly ran out.

When German bombing threatened in 1939 his parents sent him (and the girls) to the United States, where he spent three years in middle school. There he found the environment freer with more emphasis on individuality than the conformism stressed at home. He was neither athletic nor bookish. He had a ear for music and accents, playing the violin quite well (sometimes in public) and mimicking teachers to the amusement of his peers. That combined with a theatrical bent, though he did not act in school plays. He craved to be the centre of attention, dressing to catch the eye, making grand entrances, and saying things to surprise or shock. This is all rather like most adolescent boys, but he did not grow out these but cultivated them as he matured. By the same token he was considerate of others, egalitarian in manner, one who looked to the future and not the past, gregarious, optimistic, and energetic, this latter being, I have always thought, an essential for anyone in politics. His American experience left him with a lifelong commitment to the Special Relationship across the Atlantic.

He had powers of concentration and a retentive memory. He would have made a good barrister, one who could absorb a brief inside out, as they say in chambers, if only he concentrated on it. If someone told him about a book he took it in, and made it his own, so that later if he told someone else about the book, it sounded as if he had read it himself. He focussed on people and he was good at remembering names. When he talked to someone – a duchess at a soiree or a dustman at a political rally — he locked onto them as if, for those moments, they were the most important people in the world. He did not fidget and look over their shoulder for someone else more important to whom to talk. These are assets in campaigning. But he was not particularly adept at debating and if challenged on a point by either the duchess or the dustman he was likely to escape with a quip or laugh.

Much influenced by family friend Lloyd George’s example, he committed himself to the Liberal Party nearly in cradle and never wavered from that though by the time he entered politics, it had been nearly extinguished. His mother was a dyed in the wool Conservative who held an elected office the local shire council, but she was unstinting in her support for his ambitious, and perhaps always hoped that he, like others who started out as Liberals, Winston Churchill and Harold Wilson, would change. He spent his years at Oxford pursuing impressive offices, ending as president of the Oxford Union. He was a very poor student and barely completed the law degree and only passed the bar examination on a second or third sitting thanks to the great effort of a chum to prepare him. He was an indifferent barrister, best at appealing to a jury’s emotions and completely unaware of points of law or court procedure, with no grasp of detail, as more than one judge said. His real interest was always politics.

While a student he campaigned often for Liberals in General and By Elections. When he was old enough, rather than vying for one of the very few safe Liberal seats, which might have been possible due to retirements, he picked a rock-ribbed Conservative constituency that had not voted Liberal in two generations, and set to work and seven years later he was elected. The man had application.

He made little money from law, but when ITV was born he applied for a job there and become the host for a popular science program. In an age when all television was live to air, he was just the man, an easy manner, a ready smile, a quick wit, an adroit ability to segue over cracks in the proceedings. He became a reporter on international news and went to Africa for the independence celebrations in Ghana, and he kept travelling and reporting as the Empire converted itself to the Commonwealth. He met and befriended many of the leaders of the emerging nations in Africa, and did his best to explain their causes to his audience in Great Britain. He had a career in television for some years while still practicing law, when there was client, and working in the constituency. Television gave him exposure but very little money. He practiced law in the constituency, too, at cut rates to establish himself. For years he wore his father’s clothes to save money but that also made him seem a dandy from another age that appealed to his sense of theatre, and he lived at home with his mother in Surrey from which he travelled on British Rail to London and North Devon, the constituency, and in all those hours on trains, he chatted up one and all, some of whom recognised him from television and he lapped that up. The man loved an audience. The first time he ran in North Devon he doubled the previous Liberal vote and lost. Four years later he doubled it again and won.

When Jo Grimond retired as Liberal parliamentary leader, Thorpe became leader of the ten Liberals in the House of Commons. Though the Liberals were then a tiny party in electoral terms they retained an elaborate party organization from the days when they were a governing party, councils, assemblies, committees, and boards in profusion. Thorpe proposed changes to streamline that but those who sat on those councils, assemblies, committees, and boards resisted, though they did next to nothing to promote the Liberal cause in the electorate. He then did the next best thing and ignored them. He had three jobs: member of parliament, barrister in London, and travelling correspondent for television, and now leader of a parliamentary party. It was too much even for him, and he quit the law which brought in less money than the cost of the chambers.

In politics he was a vigorous champion of human rights, at the forefront of many campaigns against apartheid in South Africa and the rebel regime in Rhodesia. He also espoused equality for women and recognition of homosexuality in British legislation. He likewise advocated British entry into the European Community. The high water mark of his career was 1974 when the Liberal won 20% of the vote and in the consequent hung parliament, the prospect of a coalition government arose. The Labour leader Harold Wilson wanted another election, not a coalition. Edward Heath, the incumbent Conservative Prime Minister conferred with Thorpe, but Heath refused to consider electoral reform, i.e., proportional representation, ending that brief episode. Sound familiar? In 2010, for those who have not been paying attention, the Liberals entered a coalition with the Tories and for their trouble were obliterated in the 2015 British election to the benefit of the Conservatives.

Bust of Thorpe in the House of Commons.

Bust of Thorpe in the House of Commons.

In this period Harold Wilson, first as leader of the Opposition and then as Prime Minister, encouraged the Liberals because they siphoned most of their votes from the Conservatives. Accordingly he always treated Thorpe well, invited him to events, praised his speeches, allowed him some patronage to distribute, enacted legislation that gave tax benefits to those who contributed to the Liberal Party, sent cars to pick him up…. By contrast Edward Heath found Thorpe a poseur of no substance, and could hardly abide him and made no such efforts to court him or the Liberal Party. What a triumvirate! Heath the detail-minded plodder, Wilson the wheeler-dealer, and Thorpe the razzmatazz showman.

Ted Heath, Jeremy Thorpe, and Harold Wilson.

Ted Heath, Jeremy Thorpe, and Harold Wilson.

The few people who remember Jeremy Thorpe today most likely recall the debacle that ended his career in 1976 when his name was regularly in 30-point type on newspaper screamers at every tube station in London and throughout Great Britain. He was a homosexual at a time when homosexuals in important positions were, in addition to the social, religious opprobrium, and illegality, were regarded as security threats thanks to Guy Burgess. Added to the animal satisfaction, in Thorpe’s case there was the added appeal of the secrecy, melodrama, and theatricality of secret homosexual liaisons. Such was his discretion that even well-known homosexuals who knew him did not realise he shared their orientation, though in time he became less and less discreet. The author gives quite a compelling account of how homosexuality meshed with Thorpe’s personality without descending into the prurient details of an ABC interviewer. Though a good number of people came to know of his homosexuality over the years, including the police and security services, they turned a blind eye but I am not sure why because as Liberal leader he had access to security and defence briefings. There many boyfriends and they came and went. But one of them, Norman Scott, plagued him for years and years and years. Asking for money, bragging to others of his hold on Thorpe, writing letters to Thorpe’s mother, appearing at Thorpe’s parliamentary office. Scott was by all accounts mentally disturbed though he was good looking and could be personable in short bursts. Thorpe tried for years to find a niche for him, securing a number of jobs for him while giving him money. Scott soon wore out his welcome at the jobs and came ever back to Thorpe for more, and more, and more. He even denounced Thorpe to the police who duly noted the allegation and ignored it, noting that Scott had spent time in more than one asylum.

In 1976 Scott’s life was threatened by a man with a gun who killed Scott’s dog. Did Jeremy Thorpe have anything to do with this…well, there is the mystery? He resigned as leader, very reluctantly, under great pressure from his parliamentary colleagues. Three years later there was a trial for conspiracy to commit murder and Thorpe was one of four arraigned, and it all came spilling out in every last detail. It was a feast for the carrion of the media and every morsel was chewed, belched up, and chewed again. His legion of friends and admirers melted away. The men involved, apart from Thorpe, were dubious characters and with chequered histories. Several were accomplished and repeated liars, and should they now be believed? In the end they were acquitted and Thorpe tried to turn that into a victory, but in the course of the trial a great deal had come out of the tube that would not go back. He ran again for parliament and lost….

In the midst of this sage with Scott, Thorpe married a women who knew his homosexuality but like many others found him engaging, and she enjoyed the glamor or Westminster, lunches at the Palace, trips to exotic Africa, and so on. Moreover, they shared intellectual interests in art and architecture. Many observers have since said that he changed as a result, became less theatrical, more relaxed, more confident. Thorpe timed his surprised wedding to upstage a coup against his leadership in the party, and it worked a treat. She was killed in a car accident two years after marriage and he went into a stunned silence for a year and a half. Emerging only occasionally to perform his public duties. He did re-marry on similar terms and this women stuck with him through the ordeal of the trial.

The book is lively and replete with incidents and colourful characters but at 600 pages the detail is so great, the names carpet bombed that I was lost most of the time. The pages are dotted with endnotes to sources of the assertions made and events reported, and replete with asterisked explanatory notes on the characters at the bottom of every other page or so. The author worked on this study over a 25-year period, interviewing everyone and anyone who knew, saw, worked with or against Thorpe, including Thorpe himself. It is all very dense. The length might also seem disproportionate to Thorpe’s achievements. As far I could tell, despite his many pronouncements no cause, no legislation depended on his advocacy his voice, vote, or his action. On the other hand, had he been silent or opposed these matters, then perhaps their progress might have slower. And he was one of the founders of Amnesty International, a tireless advocate for European union, and an effective publicist for the British Commonwealth as a model of cooperation. Even more impressive is to know that many of his most compelling speeches were unscripted.

In common with most contemporary biographers, Bloch says nothing at all about religion in Thorpe’s life, though I expect his parents were churchgoers and he must have been, too, as a child and boy. Not quite, there is one reference half way through within wife died and Thorpe spoke of the spirit living on.

There are a lot of might-have-beens in Thorpe’s story. Had he joined Conservative or Labour he would certainly have made it to the front bench and perhaps leadership. Had homosexuality not been illegal and socially unacceptable, he would have perhaps been even more successful as Liberal leader, because hiding his life as a homosexual must have drained a great deal of energy and concentration from his day job, and hiding it finally undid him. Had he followed the advice of several friends to call the bluff of his nemesis and get it over with once and for all even that meant going public, he might have weathered it.

Michael Bloch

Michael Bloch

The book delivers on the potential seldom realised in the biographies of showing that the boy fathered the man. The traits, attitudes, postures, affectations of young Jeremy formed the man he became. Indeed it does that explicitly and effectively.

Skip to content