Listening to John Stuart Mill’s autobiography reminded me of a story by Miguel de Unamuno (1864-1936), a pioneer in existentialist fiction and philosophy in Spain. That name by the way is Basque and though ‘Unamuno’ clearly means ‘one world’ it is not from any known language. In this as in other ways, he was one of a kind. He wrote fiction, poetry, drama, and essays.

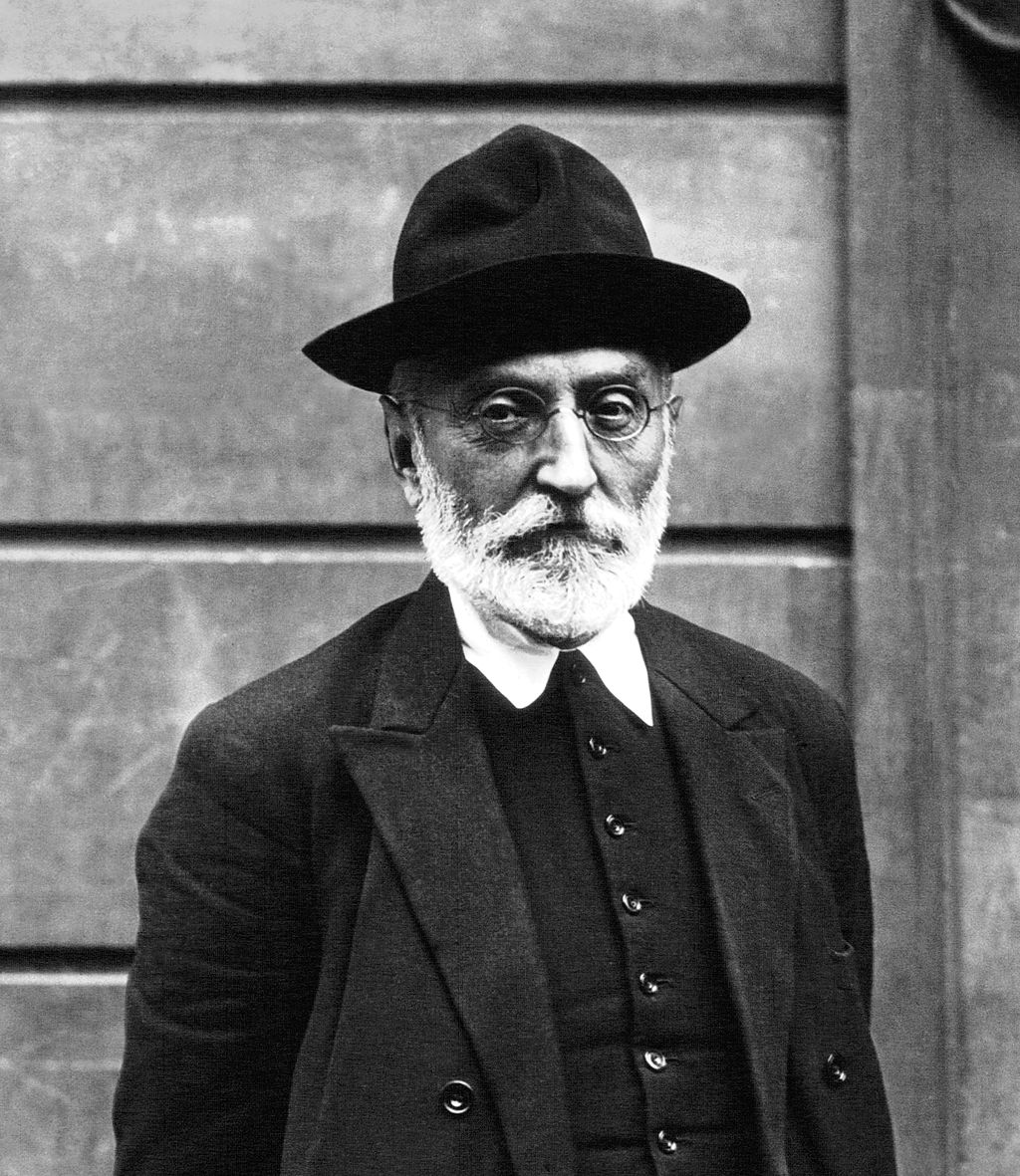

Miguel Unamuno in 1925.

Miguel Unamuno in 1925.

When Mill talks about losing faith in unified and theoretical solutions to human problems, it echoes Unamuno’s story ‘Saint Emmanuel the Good, Martyr’ of the eponymous priest who loses his faith in God and yet continues to minister with continued dedication to ease the lives of his parishioners. It is a very moving story of self-sacrifice, told in a slow and subdued manner over sixty (60) pages. The scene in the confessional when he, the priest, confesses to the young penitent Angelica his loss of faith is remarkable. Readers will long remember Don Emmanuel and his daily struggle to act as though life has meaning.

The second story is ‘The Madness of Doctor Montarco’ which is social criticism, and daring for the time and place. Montarco is a fine physician and as a pastime he writes and publishes in newspapers and magazines ever more farfetched stories which we might label as fantasy or science fiction. His patients begin to doubt his ability and reliability because of these stories, despite the evident fact, attested to by other doctors, that he is treating them very, very well. The patients lose confidence in him and desert his practice, and as this happens the stories he writes become ever more bizarre and disturbing to readers, until he finally enters an asylum to live out his remaining days a confused and broken man. It is a story about the fate of those who do not conform to the narrow channels of the Catholic and conservative society of Spain which rejects this re-born Don Quixote. This is a twenty (20) pages story.

The title story is a short novel of 176 pages, ‘Abel Sanchez’ in which Unamuno tells anew the tale of Cain and Abel in contemporary Spain circa 1930. It is a marvellous study of the jealously, envy, and madness of Don Joaquín (Cain), another doctor, who hates his best friend Abel Sanchez for all his apparently easy success in life and love, and Joaquin plots his downfall. I read the first sixty (60) pages in a gulp. Abel is a painter whose work acquires much recognition and financial success and leads to his marriage to Joaquín’s cousin, Helena who had earlier refused Joaquin’s proposal. He, the man of science, who saves lives is shadowed by this frivolous artist and trumped by him at every turn. Yet such is Unamuno’s artistry that Joaquín is largely a sympathetic character, as are Abel and Helena. That is the tragedy, there are no villains here and yet there is destined to be a collision.

By the way all three of these works were put on the Index Librorium Prohibitorum, forbidden to Catholics.

The tattered copy I read was an undergraduate text from my college days for which I paid $1.25 in 1967. I have read and re-read it several times since.

The dictatorship of Primo de Rivera exiled Unamuno to the Canary Islands from when he escaped to live just across the border in France. HIs writings were considered incendiary, including the works of fiction above. He returned when the Popular Front government took office in 1936, though one can hardly describe him as a liberal, a socialist, a communist, or an anarchist. He was a staunch Catholic but one who could see the reality behind the curtain. In any event when the Civil War came he denounced it very publicly from the lectern in Salamanca where he was rector of the university with members of the junta sitting in the audience and on the stage while he spoke. It must have been electrifying to see this hunched and weary old man challenge the Goliaths in their gold braided uniforms and sidearms. He was nearly lynched on the spot.

Passing through an angry mob of Nationalists.

Passing through an angry mob of Nationalists.

He died a few weeks later. Federico Garcia Lorca was murdered even earlier that year, he being another genius of Spanish letters. There are now monuments to both of these writers, but none to the men who killed them.

Skip to content