‘Voltaire in Baltimore,’ said one admirer of the iconoclastic H. L. Mencken (1880-1956).

When I moved the copy of ‘The Creed of the Sage of Baltimore’ on my office pin-board a few weeks ago to re-arrange things, I posted it on Facebook. Doing that reminded me I had read William Manchester’s biography of the Sage in 1980. Now seemed a good time re-new acquaintance with this original. Trusty Amazon not only found a copy for me, but also revealed that there had been a second edition which I quickly acquired. To call Mencken an ‘original,’ as Manchester does is right, but it hardly seems enough – unique is better. Love him or hate him or both, he was one of a kind, a singularity.

This was a journalist who carried a baseball bat down his pant leg when he went to do interviews, supposing, rightly in some cases, that his questions would provoke physical violence, and he would have to defend himself. This was a newspaper editor who kept a shotgun on his desk when receiving complaints, a near daily occurrence, from members of the public. He would listen but he would not be cowed, that was the silent testimony of the shotgun. If the complainer was cowed, so much the better.

As a boy in the streets of Baltimore, he became fascinated with the machinery in a local shop, as many boys have been fascinated by trains or trucks. The local shop was the neighbourhood weekly newspaper/newsletter. He stood for hours after school watching it. His father gave him a toy printing press and was thus born ‘H. L. Mencken’ when he printed his own business cards with it. He had always gone by the name ‘Harry’ but all the ‘r’ letters in the set had been broken in his first experiments with it, so he styled himself ‘H. L.’ and it stuck.

When he left high school he applied for a job with the ‘Baltimore Herald’ and by persistence made a go of it. He loved the life and went at it like there was no tomorrow. This was a pace he continued for the rest of his life. But the newspaper’s readership fell in a very competitive market, and the desperate editor turned him loose. He was transformed from a journalist reporting events, to a columnist dishing out opinions. Is there nothing sacred? ‘No,’ was his reply.

Sanctimonious clergymen were target practice for his daily column. When they protested in a mass delegation to the newspaper’s owner, Mencken consulted his public and private files. The public files he had collected for sometime, recording incidents of clerical misdeeds with altar-boys, collection boxes, choirgirls, prostitutes, loan sharks, gamblers, you name it. These he recounted with unequaled enthusiasm. Still the clerics protested, so Mencken went to the private files.

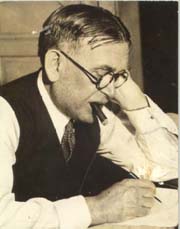

Mencken in his prime,

Mencken in his prime,

When he was but a reporter going where he was sent, doing what he told, he was a police reporter, and he was a very sociable drinker with police officers all over Baltimore. They provided him with still more dirt on churchmen that had not yet reached the public record. What a motherlode of gossip and libel did he find, and he did use it, having first mastered the libel laws! The clergy beat retreat, and having won, Mencken did not pursue them. There was still bigger game to hunt in the jungle of the sanctimonious.

Now blooded, he turned to the Baltimore political machine whose Mayor aspired to the spoils of a national office. Once again he published juicy extracts from the public record, connecting the dots, then he turned to the selfsame police officers for more dirt, which was supplied. But even that did not seem enough for so elephantine a target, so Mencken advertised in his column for citizens, in the strictest confidence, to confide in him information about the mayor. They did. Even he was surprised by the rapacious venality thus revealed, but this was a man for Augean stables. He treated it like a baseball game and created a scorecard, with day by day results in the race to the pennant.

His heritage was German, like many others in Baltimore, and he was proud of it. He loved German music and played the piano well on musical evenings with, first, the family, and then drinking buddies. When the Great War started, he saw it as Germany civilising Europe, and if Belgium, France, England got in the way, tough luck! His daily columns, whatever the subject matter, included an encomium to the Kaiser, Germany, mythical Germania, Bach, Nietzsche, or something else explicitly German. As the war went on and American neutrality leaned to Britain, he kept at it. While many Americans of German extraction admired his audacity, they kept their heads down.

His editor hoping to edify and distract him, sent him to Europe to cover the war. Europe? The editor gave him a steamship ticket to Southhampton and train ticket to London. The train ticket was never used. He changed ships at Southhampton for Oslo and then Copenhagen, and then bought his own train ticket to Berlin. Thence he proceeded to file dispatches from the Russian front, extolling German civility, cuisine, beer, courtesy, efficiency, etc. The editor cut off his funds and Mencken returned unrepentant. But seeing the war fervour back home, thereafter he had the wit to keep his own head down, but he never forgave Woodrow Wilson.

Then he turned his talents to editing a literary magazine. He it is that created the house style guide. His was the first to offer this service to contributors. Likewise he also was the first editor to declare what kind of stories he would publish as a guide to authors submitting. Finally, he vowed to treat authors with consideration and courtesy which was not the norm then or now. Submissions were reviewed and returned within 48 hours, and the letters of rejection or acceptance were hammered out on his typewriter. Those rejected got comments on the strong and weak points of the submission sometimes coupled with suggestions of other publications to try, and those accepted were bathed in flattery before he indicated just how little he could pay contributors. Having himself been rejected by editors with curt form letters rather like the disdainful treatment meted out by Qantas cabin staff when I used to fly with that carrier, he was trying to do unto other authors as he wished other editors to do unto to him.

In time he published stories by James Joyce, Sherwood Anderson, Scott Fitzgerald, Willa Cather, Theodore Dreiser, Edmund Wilson, Ernest Hemingway, Sinclair Lewis, Eugene O’Neill (plays in this case) and still more, when no one else would. He also pushed a young Alfred Knopf into publishing.

Perhaps his most lasting personal contribution was ‘The American Language’ which he prepared while staying his pen during the Great War. He was in part inspired to defend Americanese against the British, and their American sycophants, and so it was in part his private war against England in support of Germany. The other inspiration was the black slang he heard in the streets, the saloon talk of polyglot Baltimore, and frontier language of the west which he mostly knew through the works of one of his most beloved writers, Mark Twain. He likened Americanese to a new species of animal, living by its own rules in a new environment, quickly growing away from its origins (Britain). This was a hobby project but when it was published it obtained instant commercial and critical success, though he offended the self-appointed guardians of the King’s English stationed in the United States, and a war of words about words ensued.

HL doing what he did best, editing,

HL doing what he did best, editing,

These guardians should have known better than to take on this master of polemic, venom, and invective. The more so because he had researched the material for many years before assembling it. Ergo, he had it down pat, and he shoved it down the throats of the guardians who assailed him. In time this grew to be a three-volume work, as he tinkered with it for the rest of his life.

The Scopes Monkey trial is well known, and he was the conductor of the orchestra there. He recruited Clarence Darrow for the defence and blackmailed his paper into paying Darrow’s considerable fee.

He fought Prohibition in every way, from brewing his own beer to the pages of the newspapers far and wide and insulted, mocked every dry clergyman, condemned whole swaths of the nation for supporting such idiocy and just would not shut up. This fight gave him an even greater national profile, since many intellectuals, with secure private supplies from bootleggers, did not fight the good fight on this one.

More battles followed. One of his magazines was ‘Banned in Boston’ as was much else at the time, and he let it go, but when the Bostonians started bragging about caging the Beast of Baltimore, what was a man to do, but fight back? He went to Boston Common and sold copies of the offending magazine himself where he was arrested. At the police station he regaled his incarcerators with stories from his days as the police roundsman in Baltimore, while his lawyer did the heavy lifting. The scorecard read: Mencken 1 – Boston Banners – 0. The judge, who had been handpicked by the Banners, found for Mencken, free speech and all that.

When the good citizens of a Maryland Eastern Shore town lynched a negro, dragged from a hospital bed, Mencken fired his heaviest artillery. These great men proved everything he had ever thought about the scum of the earth. Did he go hard! Wallop! When commercial and physical threats against the newspaper and his person rolled in, he redoubled his invective. Crosses were dutifully burned. Dead animals left on his doorstep. All the tricks that are still in the Tea Party playbook were used. Nothing stopped him. He just kept at it until the villains went on to other, softer targets. Remember what I said earlier about the baseball bat and the shotgun.

Alas, Manchester includes none of Mencken nonpareil coverage of presidential nominating conventions and elections. He loved the circus, and democracy offered the biggest and best one for free. He was present at the hung convention in 1924 and must have had a lot to say about that. By the time he covered his last presidential convention in 1948, he was a bigger celebrity than most of the candidates. Journalist crowded around to interview him, while hapless candidates milled around the auditorium talking to each other.

He was an iconoclast who attacked hot air, bunkum, lies, pomposity, pretention, vain-glory, stupidity, ignorance at every turn, and if one attack was good three or four were better. Indeed, his modus operandi became so well known that one well-meaning friend asked him if there was anything he did believe in, and the result was the Sage’s creed.

Manchester offers no summing up of Mencken’s life, legacy, or impact. My own is this. Puncturing balloons is great fun, and there are plenty of hot air balloons around to puncture, and most of them have so little self-knowledge that they do not know that they are full of hot air. In this, as in so much else though, one has to know when to quit, and Mencken did not. He was like a Groucho Marx who just keeps rabbiting on ridiculing all about him, and with age Mencken became far less discerning in the targets he selected. Neither the Great Depression nor the rise of Adolf Hitler could he take seriously and so his star waned. Just as William Jennings Bryan clung to old verities, in his age so did Mencken.

William Manchester

William Manchester

Moreover, Mencken was not wholly negative. He loved baseball his whole life and never said a bad word about it, not even during the Black Sox scandal. He had a blind eye there. Manchester barely mentions the sport but one reason Mencken went to New York City as often as he did was to see Yankee games.

When I visited Baltimore for a conference, I spent far too much time conferring, and did not make it to the Mencken Room, which is only grudgingly open now and again. Likewise I did not do an Edgar Alan Poe homage such was my professional fervour, long since outgrown. I did make it to an Orioles game though! I did go over the submarine in the harbour, and I did see Fort McHenry from the water with a boatload of sozzled conferees.

The second-hand copy Amazon produced is marked up, doing the same myself with most books I read, I sometimes wonder about the marker. Is this someone I would get along with? I try to see some pattern in the mark-up. The marks in this book seem to be analysis of Manchester’s style, his choice of voice — third person past, the mix of description and anecdote, the passive versus active voice. I wonder if the writer was an author. The copperplate penmanship suggests a woman but I have been fooled on that before.

Speaking of marked up texts, as an undergraduate, I had developed a method for selecting used textbooks that worked perfectly.

First I only looked at copies that were highlighted in yellow. Why? Read on and be enlightened. Second I concentrated on those yellow highlighted copies that were densely marked in the opening chapters. Yes, there is a method to this. And remember I was buying in a crowded bookstore with many other students getting books for the semester, so there was physical and social pressure to get on with it.

Ah, the method? I discovered by the end of the freshman year texts that were marked in yellow were used by dolts more interested in the yellow marker than any meaning the text might impart. The yellow highlighter was a novelty in those days and only a few students used them, and they used them, it seemed, more as a status symbol than anything else. Why do I say that? Because the highlighting stopped within a chapter or two. Either the reader dropped the course, give up to failure, or relied on copying the work of others. Law One was: A text highlighted in yellow was likely to be clean after a few chapters.

As a corollary to this law, I also noticed that the more densely marked the first chapter was, the sooner the marking stopped. Someone who highlighted every line on page one, had no idea what was important and what was not. Such an indiscriminate marker was destined, know it or not, to drop even sooner than the average Yellow-Head, as I called them to myself. Law Two was: the more frequent the yellow in Chapter One the sooner the highlighting would stop, leaving the remainder of the text untouched.

A few times a friend expressed surprise to see me pick a book that was heavily marked in the opening pages, but I gave a spurious reason, about that marking saving me the work of doing it myself, rather than reveal the two laws above! These I kept to myself until now.

Mencken’s Creed for those too lazy to look it up for themselves. It is sometimes edited to suit the quoter.

I believe that religion, generally speaking, has been a curse to mankind – that its modest and greatly overestimated services on the ethical side have been more than overcome by the damage it has done to clear and honest thinking.

I believe that no discovery of fact, however trivial, can be wholly useless to the race, and that no trumpeting of falsehood, however virtuous in intent, can be anything but vicious.

I believe that all government is evil, in that all government must necessarily make war upon liberty and the democratic form is as bad as any of the other forms.

I believe that the evidence for immortality is no better than the evidence of witches, and deserves no more respect.

I believe in the complete freedom of thought and speech alike for the humblest man and the mightiest, and in the utmost freedom of conduct that is consistent with living in organized society.

I believe in the capacity of man to conquer his world, and to find out what it is made of, and how it is run.

I believe in the reality of progress.

I – But the whole thing, after all, may be put very simply. I believe that it is better to tell the truth than to lie. I believe that it is better to be free than to be a slave. And I believe that it is better to know than be ignorant.

Skip to content