Reading about John Stuart Mill brought to mind Mr Utilitarianism Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), and I remembered that I had acquired a copy of this book years ago as relevant to utopia, though many might suggest one criterion of utopia would be the absence of insufferable bores like JB, as he referred to himself. While not a biography, the book does convey much of Bentham’s personality and habits.

The subtitle explains the remit of the monograph, ‘An Account of his Letters and Proposals for the New World.’

JB proselytised far and wide in England. He started out in law but when his parents’ deaths left him well off he became a full-time know-it-all. He wrote one tract after another, many are legal in orientation, and sent them off to one and all to influence opinion and incite action. He eschewed running for parliament on the ground that the duties thereof would distract from his broader and deeper influence. He ranged over many subject and topics, ignorance being no bar. Altogether a public intellectual!

Then he hit on the idea of the panopticon and devoted himself nearly exclusively to that for years, and sunk a lot of his own money into it. It started out as a model prison but as he honed the idea it became a more general social model. It is all in the name ‘pan’ = ‘all’ and ‘opticon’ = ‘seeing.’ All-seeing, a building made of glass so that everyone could see what each person is doing at all times. Little Brothers and Sisters are always watching! The social discipline born of this exposure would put us all on our best behaviour all the time. Michel Foucault has some things to say about this that are worth reading.

Disaffected by the failure of the Great British to embrace his panopticon, JB turned his gaze to the wider world, and there he saw Spanish America. This was a greenfield site in his mind. New societies were aborning there, and if they started off on the right foot, they would grow into perfect little Benthamic societies. He would be only too glad to tell them about that right foot.

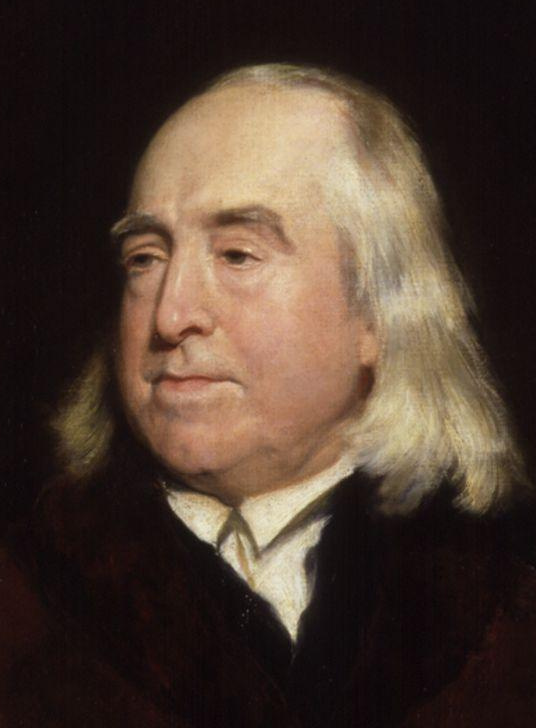

God’s gift to humanity, Jeremy Bentham

God’s gift to humanity, Jeremy Bentham

Cue, another prodigious letter-writing campaign, and more tracts. Since he paid for the publication of his tracts they were not edited, and seldom reviewed. That may explain why most of them are so excruciating bad. Neither self-criticism nor second-thoughts featured in his personality. His contemporaries can be grateful that for every tract published he wrote two others that had to await posthumous publication in his collected works now safely confined to research library shelves for the terms of their natural lives.

The circumstances were a bit tricky, as reality can be. While Spain still claimed and asserted suzerainty over Spanish America, and these claims and assertions were largely respected by European powers, the Spanish Americans were rebelling against rule from Spain, imposed locally by appointees whose main goal was to enrich themselves with the least possible effort. San Martín, Símon Bolívar, and others were in revolt. These niceties did not bother JB, he wrote to Madrid, to Spanish colonial governors, and to the rebels offering his services as a lawgiver. Solon, reborn! Have laws, will travel.

In doing so he promoted his own considerable expertise as evinced by his numerous tracts, which he usually enclosed with his letters, and he cited testimonials from heads of states (who had never heard of him), savants (who regarded him as a crackpot), and religious leaders (who rejected him as an atheist).

Never one to stand on ceremony, while he was wooing the Madrid government to let him dictate to its restive colonies, he managed to find time to offer 400 pages of criticisms of the Madrid government, its constitution, its acts…. What a pompous prat, one might think.

More seriously, he suggested that his complete ignorance of local circumstances, and existing manners and morēs (or knowledge of Spanish) ideally suited him for the job, leaving him dispassionate, detached, unfettered, and rational. In short, he claims some of the qualities that Plato ascribed to Philosopher-Kings, though he never cites Plato, or anyone else for that matter. It is JB all the way, unalloyed.

He did make plans to travel to Mexico at one time, and then at another Venezuela but neither eventuated. Nonetheless, he continued his barrage of letters and tracts.

Imagine now a besieged Spanish governor in Peru with insurgents at the door, nearly all communication to the interior cut by Indians, receiving a letter…from Bentham running to 25 pages about whether the legal code should be written in italics or not. Bentham often seized on such trivial details and spent pages and pages on them, while the castle burned down. He had neither practical sense nor political nous. Though, surprisingly enough, some of his correspondents did take him seriously like Símon Bolívar, giving me cause to doubt SB’s wisdom. (Maybe I should read a biography of SB.)

Williford charts all this deadpan, resisting all but a few asides on the evident megalomania. This is an excellent, short monograph that shows a considerable volume of research, effectively marshalled to say what needs to be said with little fuss. Perhaps it started as PhD but if so the published version escaped the PhD-to-book syndrome – overkill.

I could not find a picture of the author.

I confess that I have a marked up copy of Bentham’s ‘Fragment on Government’ which I had to read in a graduate seminar, and I cannot remember one thing about it, except the relief at never having to look at it again.

In pursuit of John Stuart Mill I have also recently read Eric Stokes, ‘The English Utilitarians and India’ (1989) which I chose not to review, finding it so densely detailed that only a specialist in British colonialism in India could fathom it. I certainly could not, though I found informative the distinctions Stokes made among the Whig, Liberal, and Utilitarian approach to India. For the Whigs government itself is the enemy. For the Liberals education solves all problems when mixed with time. For Utilitarians there is no substitute for telling people what to do, how to do it, when to do it, and, if time permits, why to do it.

By the way, when Bentham’s parents’ estate was divided between the two sons, his brother took his half of the dosh and moved to the south of France to pursue the life of a sybarite. Who can say which was the greater service to later generations?

Skip to content