This is a personal memoir of a French officer who was on the front line in Flanders in 1940 during The Defeat. He was a supply officer who managed fuel for tanks, ambulances, motorcycles, cars, and trucks with Henri Giraud’s First Army. Bloch was a professor of history at the Sorbonne, and he volunteered to serve in 1939 again, having been an infantry captain in World War I. Some may recognise the name for Bloch was also a remarkable historian whose two volume study, ‘Feudal Society,’ is one of the most compelling works of history I have read.

Bloch wrote ‘Strange Defeat’ as a diary in the last months of 1940, and it remained unpublished at his death in 1944. He was in the Resistance, arrested by the Gestapo, tortured for information, and then murdered. None of this figures in his pages but it is a grim reminder of the mortal gravity of the place and time.

Bloch muses on his own reactions to the approach of war and his decision, at age fifty-two, to take up arms again and reflects on the men with whom he served, and analyses the Defeat from his captain’s eye-view.

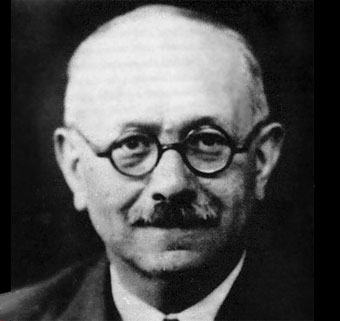

Professor Bloch of the Sorbonne

Professor Bloch of the Sorbonne

He emphasises that the military shibboleths of order and method could not bend but they could break. That is, there was little sense of urgency when the German attack began. He had fuel requisitions rejected because a corner of the page was torn or the ink had run, which meant a long drive back to complete a new copy and get it signed by field officers whose troops were engaged with the Germans, and then return along roads strafed by the Luftwaffe. None of these exigencies were sufficient to compromise protocol. There was all the time in the world, until time ran out and then panic set it.

Even when the First Army retreated, it did so at a leisurely pace, moving back twenty kilometres. His point is that the insistence on procedure and these short retreats were measured against trench warfare of World War I, not against the mobile warfare of the Panzers. A twenty-kilometres retreat was but less than an hour from the next tank attack, which was never enough time to re-set the line of defence. Yet French Army doctrine would not permit a longer retreat, and so nothing was available to facilitate it in the way of equipment, road signs, traffic controls, communication, identified positions, marked map coordinates, and expectation. (To retreat a longer distance required an order from Supreme Command and Supreme Command could only reached by courier and no courier could get through. Supreme Command refused radio and telephone communication even in distress.) The First Army then retreated in these bite-sized steps five or six times before it completely disintegrated. At each retreat more units lost contact, were cut-off by marauding Panzers, read the map sideways and wandered into a Belgian bog, or collapsed in exhaustion and fear.

Then there were the personal rivalries he saw in the career officers in the many headquarters where his duties took him. To say to one colonel that he had instruction from another colonel meant he would get no hearing at all, because these two colonels were old adversaries in the promotions list. After mentioning the first colonel’s name, Bloch watched helplessly as the second colonel dropped his requisition into a drawer and with an icy word dismissed him. Clearly that chit was going no further up the chain of command.

There are many other examples but perhaps enough has been said to make the point. The procedures were cumbersome, inviolable, mysterious, and most of all based on absolute obedience at the expense of any initiative. (By the way, German intelligence services were aware of French army procedures and took them into account in their own planning.)

Black was the day, but Bloch also met, worked with, and observed many officers who manfully did their duty despite the circumstances. More than one staff officer stayed at the radio or telephone directing retreating units to Dunkerque even as shell fire fell on them. Bloch is one of those thousands of men who spent days on the sands at Ostend as British troops were evacuated while the Luftwaffe strafed the beaches and artillery fire grew closer.

The miracle at Dunkirk

The miracle at Dunkirk

Along with more than 120,000+ other French soldiers he was himself evacuated. (Winston Churchill personally ordered the Royal Navy to make no distinction among Allied soldiers and to board them first-come, first-served. For a day or more before that order the Royal Navy had only taken Brits.)

Bloch landed in Dover, marched to the train station, stopping for tea and scones served to the group of French troops he was with at the local lawn bowls club, then onto a train to Plymouth where he boarded a ship for Bordeaux, and thirty-six hours later he was again in France. The French troops shipped back to French Atlantic ports like this were without weapons, some had lost clothing, particularly boots in the surf at Ostend-Dunkerque, some were wounded or injured, and devoid of any chain of command. Bloch and the compatriots he shipped with were billeted in a health camp near Bordeaux, where, he observes, they were received with far less warmth and civility than they had experienced in England where he and his fellows were heroes who had stemmed the tide of the Boches, but in Bordeaux they were burdensome failures.

In World War I the city of Bordeaux was a million kilometres from the front; not so in the mechanised age. No sooner did Bloch arrive than did the Germans. He became one of those poilus, dirty, dazed, ragged, head down, among a thousand others on a road, escorted by a lone Wehrmacht private with a single-shot carbine, marching into captivity.

Les poilus

Les poilus

At fifty-two the Germans deemed him too old for slave labour in the Reich and he was paroled to begin his career in the Resistance shortly thereafter.

A book to be read in parallel with ‘Flight to Arras’ from the pen of Antoine de Saint-Exupery, he of the ‘Little Prince.’ St.-Ex was an air force pilot who flew combat in 1940, then fled to Algeria to continue the war with the Free French. He, too, died in 1944 while on a mission.

Skip to content