Reading a biography of Símon Bolívar left me confused about events in Spanish America, and when Amazon’s Mechanical Turk recommended this title, I had a look and liked what I saw and sucked it down into the Kindle. Well worth the $1.12 price. This is a short guide book (just under 100 pages) that summaries the sprawling history of these rebellions, revolutions, and wars, the factions and forces involved, and the geography. The print version has coloured maps and graphics that do not show well on the Kindle but on the iPad they were superb.

Terminology first, I am tempted by habit to refer to Latin America but Fletcher makes it obvious even to the geographically challenged that Spanish America in 1809 extended to Oregon, including all the eventual United States states of California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, Louisiana, Texas, Florida, and parts of others, as well as Mexico, Cuba, Puerto Rico, St Domingo, and everything south to Tierra del Fuego with the exception of Brazil.

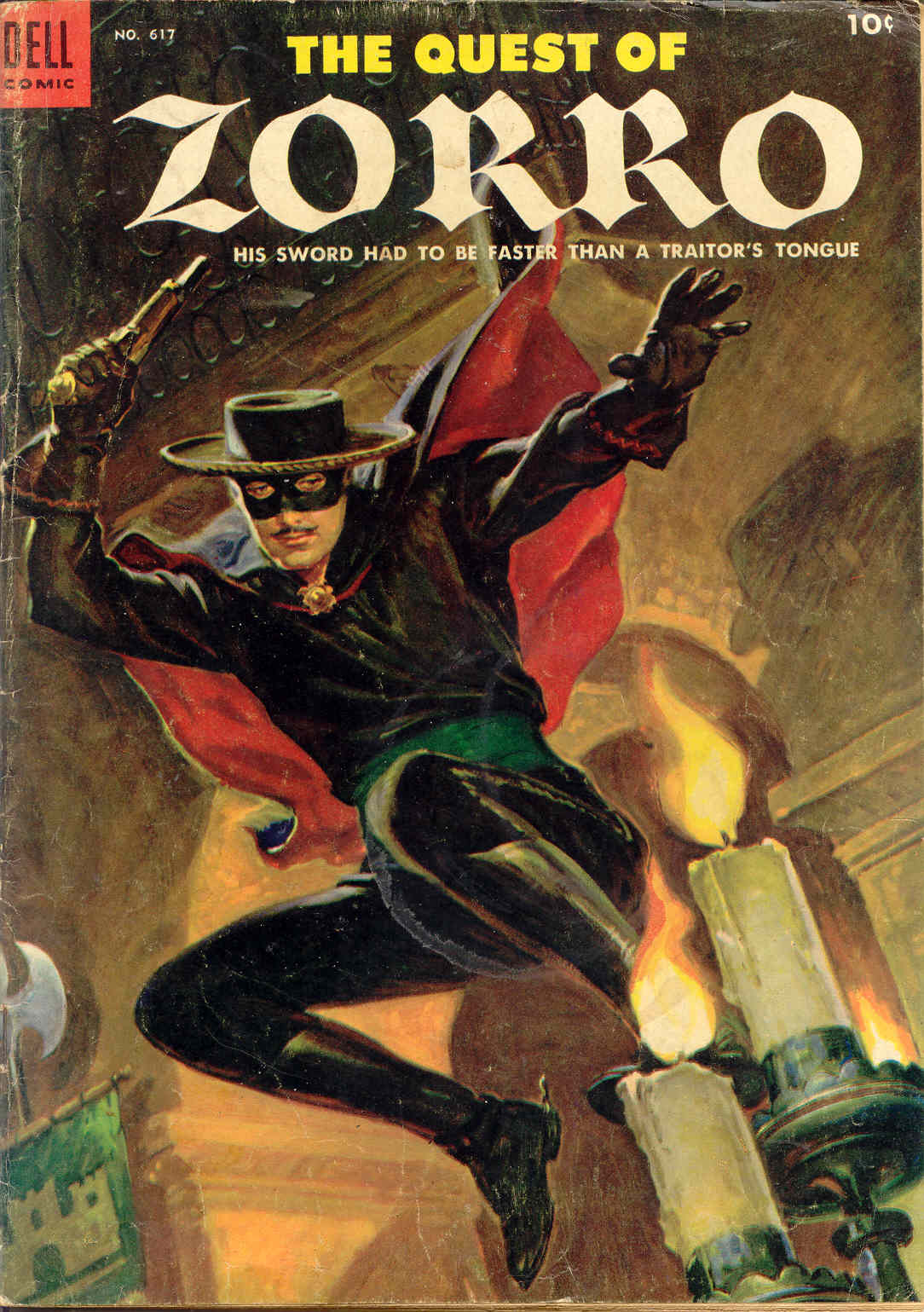

Second, it turns out I knew a little more than I thought, since I had watched Guy Williams (Zorro) fight the corrupt and incompetent Royalist regime in Old California while I was coming of age on the Rio Platte. Though Don Diego de la Vega is pretty vague about dates, it still turns on themes relevant to the 1809-1829 period. a distant colonial master, local villains, indians and blacks with no love for the regime. Locally-born Spanish Europeans taxed and abused by Spanish officials who steal all they can before returning to Iberia.

Third, I appreciated Fletcher’s deft summaries of the shifting divisions and alliances among both the Patriots and Royalists. Even those names are inadequate, but some labels are necessary. A score card is necessary to tell all the players, and at times they change uniform numbers, necessitating a revised score card. More on that below.

Among the American population were the three races and various combinations of them: Spanish, Indians, and blacks. When the shooting started the Spanish had been living in the Americas for nearly three hundred years. They were set in their ways. The Roman Catholic Church was a major factor. The Inquisition was hard at work in the New World.

Haiti loomed large in the minds of all Spanish, as it did in the southern United States into the 1860s. The slave revolt there confirmed the worse nightmare of many while confounding stereotypes. The blacks massacred their owners went the story, and took over, defeating two Napoleonic armies sent to teach them to respect the white man. Black slaves defeated two European armies!

There were divisions among the Royalists. Some wanted to continue the monarchy, but who was king, the old king clinging on, his usurping son, or Napoleon’s puppet. Moreover, some Royalists advocated a constitutional monarch and spoke less of a king and more of a constitution. In addition, in metropolitan Spain there were those who wanted no king of any kind, but did want to retain the empire. Each of these slivers of opinion was reflected in the Americas.

Among the Patriots were a host of differences as well. They called themselves ‘Patriots’ who were fighting for the freedom of their countries, and sometimes for their peoples, too. But which people? White, red, black, and the shades among them? The whites were further divided into those born in America, called Creoles, and those who moved there from the Old Country. Most of the blacks were slaves, but not all. The reds had tribal loyalties. Because of the methods of Spanish colonalism, the many colonies had almost nothing to do with each other. Lima was as foreign to Caracas as Madrid.

Most of the Patriots were loyal to their province with no larger conception of Spanish America. As soon as the Royalist were driven out the provinces would fall into conflict over rivers, boundaries, mines, and symbols. Sometimes they did not wait for the Royalists to be driven out before starting a war among themselves. A Columbian army would not go to Venezuela to fight the Royalists, nor would a Venezuelan one go to Columbia. And so on and on. If there is strength in unity this was one strength they did not have. Bolívar argued that if the Spanish retained one toehold in the Americas, then one day they would reassert their claims to the colonies.

Bolívar and José San Martin were among the few who saw a larger picture, the former for political purposes and the latter for military purposes. Though Bolívar had a political goal of a united Spanish American, he was not the accomplished soldier that San Martin was, but San Martin lacked Bolivar’s vision. Nor was there much chance they could work together. Bolívar was brassy, impetuous, egotistical, as well as determined, dogged, and tireless, while in contrast San Martin was reticent, careful, self-effacing, methodical, and slow (because it takes time to think), as well as a professional solider who was a strategist of note and a tactician of creativity.

Certainly a quarter, perhaps a half, of the populations (red, white, and black) in Spanish America died in this period. Many were killed after the battles, and others died of diseases loosened by the upheavals of warfare. Though Spain was feeble, on one occasion it managed to dispatch an army of 40,000 to the Americas to end the rebellions. Whole cities were murdered after battles to eradicate the enemy.

To get soldiers both sides courted the red and black races. The Spanish approach was to offer material reward, while the Patriots offered emancipation. The material reward of money would allow a slave to buy his freedom. The Royalists did recruit some individuals this way. Bolívar in contrast would declare emancipation and then recruit blacks to fight to retain this new freedom. The worked, too, on a larger scale. As a result slavery was outlawed a generation or two earlier there than in the United States. A parallel approach was taken by each side to recruiting indians. The Spanish offered individual incentives, Bolívar emancipation from forced labor and the so-called red taxes. Likewise the Patriots recruited soldiers from the captured Royalists with promises of citizenship.

In between the Royalists and Patriots were self-serving bands of armed men that preyed on both Patriots and Royalists or made temporary alliances with either to secure booty. More fearful than any of these bandits was the pestilence and disease let loose by the destruction of waterways, wells, damns, and the like.

The end of the Napoleonic Wars meant the world was awash with war surplus, and much of it went to these conflicts from northern California to southern Chilé. Likewise, there were demobilised soldiers who had no other life and who became mercenaries on one side or the other. Men who had fought each other at Waterloo ended up comrades in the European formations of San Martin’s army. Irish Catholics driven out of Ireland by Protestant England, found their way to Spanish America to serve with English veterans of Waterloo.

Brazil and Portugal also played roles in this story, trying to take advantage of the disruption among the Spanish to settle old grievances, appropriate land, secure river access, and the like. There were armed clashes between Brazilian forces and Patriots, Portuguese and Royalists, Brazilian and Royalists, Brazilian and Portuguese, and so on. All combinations.

No sooner had the Spanish given-up and left than the Patriots fell into prolonged conflict among themselves within cities and provinces and between provinces that became countries, some of the conflicts lasted until the 1860s. That goes some way to explaining the prominent role of the army in many Spanish American states. In contrast George Washington’s Continental army was under arms for eight years, but some of these Spanish American armies were at it for fifty years, e.g., in Argentina. Just as the Prussian army made Prussia, some of these armies could claim to have made the state.

As to the book, the organisation is coherent, the prose is crisp, and the pages are free from typos.

Fletcher is a UNL graduate and now a band manager.

Skip to content