In April 1962 William Faulkner spent a few days as a writer-in-residence at a college in a small town in New York state, West Point. The book combines the typescript of the story from ‘The Reivers’ which he read (including his hand-written emendations), and transcripts of several question and answer sessions with students and faculty.

It is overproof Faulkner and there is no stronger elixir. The moral purity of the man glows. By moral I mean his commitment to lift the hearts of readers with true accounts of the conflict within and between us. ‘Morality’ does not mean telling other people what to do; it means doing the best one can at what one does. Believe it, Faulkner says it better.

He acknowledged that his novels are uneven but he loves all his children, the crooked as well as the straight, as would a mother, and learns from them each. When asked about the parochial nature of his work, he admits it, and then goes on to the eternal themes of loss, love, onus, anger, belonging, challenge, and — most of all — comprehension. Asked to say which novel is his favorite, slowly he answered, as I knew he would, ‘The Sound and the Fury’ because it hurt so much to write it, and it still hurts ‘when I read a few pages of it.’ The implication is that a few pages at a time is all he can bear.

Why is the idiot Benjy the narrator in ‘The Sound and the Fury,’ he is asked? Is it because of his childlike simplicity? No, said Faulkner, though much more politely than that, it is because Benjy does not understand what he sees, and even so the novelist must try to make it understood.

Asked about Southern racism he replies that it is a terrible disease to be eradicated by education, but it won’t be as easy as eradicating polio. No, not the education of blacks to be like whites, but the education of whites to end racism. [Maybe in another thousand years.]

The students asked leading questions right out of the textbook, and he gently turned them aside to come back to the bedrock where there are no labels, no simple either/or answers, no symbols, nothing that can go on an exam paper, just the story. Any man’s story is, in part, every man’s story, someone once said.

Asked how he plans his novels he said this:

‘A disorderly writer like me is incapable of making plans and plots. He writes simply about people and the story begins with a phrase, an anecdote, or a gesture, and it goes from there and he tries to stop it as soon as he can. It’s not done with any plan or schedule of work. I write about man in his comic or tragic condition, in motion, to tell a story — give it some order and unity and coherence.

Or in reply to a question about the value of literature:

‘Poetry is best and first. The failed poet writes short stories. The failed short story writer has nothing left but the novel. Poetry condenses everything in a few lines, the short story in a few pages, the novel… goes on.

That old chestnut is tossed in, Where do you get your ideas from?

‘It starts with a character, usually, and once he stands up on his feet and begins to move, all I can do is trot along behind him with a paper and pencil trying to keep up long enough to put down what he says and does, and maybe even thinks, but he is in charge. I have little to do with it but edit it into some coherence to lay emphasis here and there, but the characters themselves, they do what they do, not me.

Leo Tolstoy said something like that in his time.

When I visited Rowanoak in Oxford Mississippi on stifling hot day one August I beheld his well-used typewriter and the walls on which he used to doodle with his characters. He did try to use the technique he had learned in Hollywood of storyboarding for some of his later novels.

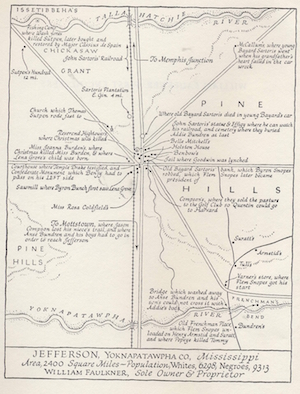

My nomination for his most powerful novel? That is easy: ‘Abalsom, Absalom.’ His most accessible novel for a newcomer who has yet to enter Yoknapatawpha County is ‘Intruder in the Dust’ and his long short story ‘The Bear.’ The funniest is ‘The Reivers.’ The most exhausting? ‘As I Lay Dying.’ The most compelling? ‘Light in August.’ The most harrowing? ‘Sanctuary.’ The most penetrating? ‘Go down, Moses.’ Each of his titles has something distinctive while they form a whole. And let’s not forget that very short story, ‘A Rose of Emily.’ I was always sure it was ‘Emily’ for Emily Dickinson.

A word of warning. Faulkner only became Faulkner in Yoknapatawpha Country.

His earlier novels like ‘Pylon,’ ‘Mosquito,’ and even the elegiac ‘Soldier’s Pay’ are pre-Faulkner. I do believe I have read them all (some more than once) and most of the stories, too, that he managed to stop short before they, too, grew into novels.

On that pilgrimage to Oxford I also recalled that it was on the campus of the University of Mississippi that there were race riots in 1962 led by the governor of that state and subdued by Federal troops. This was a time when Faulkner could not show his face on campus, where now he is honoured.

Skip to content