This book is a novel. Aqa Jaan and his family live in a house attached literally and figuratively to a mosque. In fact his family owns the ground upon which the mosque was built. Imams come and go but the Jaan family goes on and has done so for hundreds of years in the house of the mosque.

The story opens in the latter days of the reign of the Shah of Iran and ends twenty or so years later. That is, it encompasses the origins and start of the Iranian revolution that toppled the Shah, started a civil war among Iranians, led to a war with Iraq, and blood letting without end, all the while praising the God of peace. In pauses during the slaughter, there is much praying.

Leaving aside the details, the account has many, many parallels with the French Revolution, the Russian revolution, the Spanish Civil War, and no doubt others from Cuba to China and back. First the uprising, followed by increasingly brutal repression. Then victory for the revolutionaries followed by a purge, first of previous enemies, and then of tepid friends, and then as the paranoid of incumbency develops a cannibalism its own. Remember Robespierre? Revolutionaries eat their own.

Under the guise of the New Dawn, old grudges re-surface and old scores are settled with revolutionary justice, i.e., a bullet to the brain right here, right now. Anonymous denunciations are enough. Silence is betrayal. Any criticism, or hesitation is treason.

Some estimates of the death toll exacted by the Ayatollahs at 60,000. The Iran-Iraq War added another 1.5 million deaths. Iran being roughly four times larger than Iraq its military strategy was to win the war by piling up corpses. It was the same strategy General Alexander Haig favoured on the Western Front in World War I.

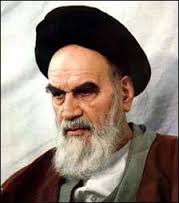

Aside from those generic features, the portrayal of the Ayatollah Komeini is interesting, and there is some explanation of the factions that existed in Iran before, during, and after the revolution.

The trials and tribulations of the Jaan family are without end, though somehow a few of them survive and retain their faith in Islam despite its bastardisation during and after the revolution. As for many others, their faith is in God, not in the church.

Some gratuitous grostequieres like the Lizard.

I read it as an Ebook on the Kindle which means only saw the cover once in a poorly rendered graphic. Ergo when it came time to type these notes I had to make a point of opening the cover to get the title right and to get the author’s name. On the title page I could not find the year of publication.

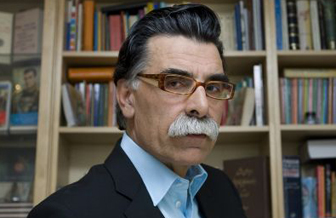

Kader Abdolah

Kader Abdolah

Translated into English from a Dutch translation. Odd that, I would have supposed the best thing is to translate from the original into English, not from Farsi to Dutch to English. Having said that, I found no faults with the translation, but then I might not but someone who knew Farsi might.

It was hard to keep track of characters because of the unfamiliar names, like those in nineteenth century Russian novels, and the over lapping webs of the extended family and the mosque.

Skip to content